When Healthcare is a Bludgeon

The injustice of US healthcare is especially pronounced in prisons and jails, where care is denied, delayed, and inadequate and sometimes even constitutes another form of punishment.

A recent report from the nonprofit Commonwealth Fund has ranked the United States’ healthcare system dead last among nine other wealthy peer nations. The U.S. scored poorly on avoidable deaths, access to care, and administrative efficiency, among other metrics. Even worse, we pay far more for this substandard care and we live shorter lives than people in the other nations in the study (Australia, Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden, Switzerland, the U.K., France, Canada, and New Zealand). Practically everyone in the U.S. has a healthcare horror story: outrageous bills for emergency room visits or ambulance rides, having to ration insulin or other medications, errors in diagnoses, insurance denials of critical equipment and services like organ transplants or wheelchairs, “zombie” healthcare providers who are indifferent or uncaring, and more. And that’s if you have some access to care—25 million Americans don’t have any health insurance at all.

The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. is credited with having said, at a 1966 conference of healthcare activists, that “of all the forms of inequality, injustice in health care is the most shocking and inhumane.” If this is true in the United States in general, it is even more true inside the criminal punishment system, where “healthcare” as you and I might conceive of it—a healing art and science, the aim of which is to improve people’s health and longevity and reduce pain, suffering, and illness—does not exist. Much like the healthcare system for non-incarcerated Americans, “prison healthcare” is not a single entity, as it varies by state and facility. But one thing we can be certain of is that healthcare in jails and prisons has always been grossly inadequate. It has always functioned as a total subversion of what healthcare is supposed to be.

Along with the isolation, degradation, violence, and abuse that are routine parts of imprisonment, people are subjected not just to shockingly bad “healthcare”—more often medical neglect than care—but to healthcare as a bludgeon. In other words, “prison healthcare” might be thought of as simply another form of punishment, torture even. Prisoners requesting care are often accused of faking their symptoms for potential gain (“malingering”) or of drug seeking. Women prisoners complaining of cold symptoms have ended up getting unnecessary pelvic examinations, which highlights the fact that, for women, “sexual abuse is often frequently linked to medical practices.” Doctors have carried out coercive medical research studies on prisoners who were desperate to earn money or get medical attention. Doctors have force-fed hunger-striking prisoners, an act widely considered a violation of medical ethics. And the ultimate punishment—the death penalty, a fate that has been inflicted upon 1,534 people since 1976—is administered by medical means: most commonly, lethal injection, or, more recently, nitrogen gas, a new method considered by veterinarians to be too barbaric for the euthanasia of animals. Leave it to the state of Alabama, whose prison system is one of the deadliest in the country, to put this experimental method into practice earlier this year, becoming the first state to do so. One anesthesiologist who read firsthand accounts of the nitrogen gassing of Kenneth Smith, age 58, in January of this year, said, the “intent here was torture.”

To take a deeper look at “prison healthcare” is to step into a litany of horrors of our own making. To think about reforming prison healthcare would require acknowledging the humanity of prisoners—the one thing that our system of imprisonment denies at every turn.

In Are Prisons Obsolete?, prison abolitionist Angela Davis quotes criminologist Elliott Currie, who wrote in 1998 that “Short of major wars, mass incarceration has been the most thoroughly implemented government social program of our time.” To fully understand what Currie was talking about, you need to get a sense of the numbers and the demographics. Imagine you are one of the approximately 2 million people currently in one of the country’s sprawling network of 6,325 state or federal prisons, local jails, or immigration or juvenile detention facilities, among others. (For readers who are in prison or jail, please bear with me.) If you end up in one of these places, chances are you are poor, Black or Native American or Latino, and have a lower level of education than the general population. If you’re in jail—around 9 million people cycle through local jails each year—you comprise around one-third of all people currently locked up, and more than 70 percent of the time, you’re there awaiting a trial. In other words, you and your approximately 500,000 fellow pretrial detainees haven’t even been convicted of anything. But you can’t go home because, in many cases, you simply can’t afford to post bail. You’re also more likely than those in the general population to have a disability, chronic health condition, mental illness, substance use disorder, or history of trauma or abuse. Increasingly, you might also be 55 years or older, in part because tens of thousands of people convicted in the War on Drugs in the 1980s and ’90s have been aging as they serve decades-long sentences in what Vox has called “de facto nursing home[s].”

What all this means is that prisoners tend to need more healthcare than those who are free. But prisoners in the United States often face abysmal healthcare—when they actually get it. Often, their symptoms are ignored or allowed to worsen until they become urgent, life-threatening, or irreversible. There are countless stories of prisoners’ bodies visibly deteriorating as they are denied care for months or years on end. Bellies swell up from failed livers or growths, extremities go numb from masses impinging on nerves, cancers that have spread to the brain cause severe pain which goes untreated. Sometimes the need for care is more immediate, and the state completely fails to render basic aid. In one particularly disturbing case that took place on Rikers Island in 2022, Michael Nieves, age 40, sliced his throat with a razor, and guards watched him for 10 minutes without offering any aid, allowing him to bleed out and die. They were found to have violated no policy and faced no criminal charges. Nieves happened to have severe mental illness, and it’s often the case that jails and prisons fail to adequately treat mental health conditions (especially suicidality) as well as substance use disorders—both of which are significant causes of death in this population. Equally disturbing is the practice of “medical bond,” when a sheriff releases a sick detainee to a medical facility so that the jail can avoid paying the cost of that care. Sometimes the person is already experiencing a medical crisis or is just on the verge of it. This can be thought of as another form of “patient dumping,” which federal law has prohibited since 1986. The practice is thought to be particularly widespread in Alabama.

The Prison Policy Initiative notes that about one-third of Americans have an immediate family member who has been to jail or prison at some point in their life. Despite how common imprisonment is, many people might not think or know much about the conditions of confinement for prisoners. Simply put, prisons are not healthy places to be. They are, in the words of prison abolitionist Mariame Kaba, “death-making institutions.” This is not an exaggeration. Everything—from the physical environment to the psychological conditions—is “designed to promote premature mortality.” The prison system has “entirely dispensed with even a semblance of rehabilitation,” write Angela Davis and fellow prison abolitionist Cassandra Shaylor. Davis has argued that the main objective of prisons is now “incapacitation.”

Here’s how Ruth Delaney and co-authors at the Vera Institute of Justice described prisons in 2018:

By their very design and aesthetics, the physical buildings and layout of American prisons cultivate feelings of institutionalization, immobilization, and lack of control among the people who live there. A typical cell is a small cement and brick box—the size of a typical parking space—with a metal or cement bed (sometimes a bunk bed) covered with a thin mattress, an open metal sink and toilet, perhaps a fixed metal desk, and a small window that is often sealed shut. Other interior spaces are similarly utilitarian in nature, with hard fixtures and fittings, cinder blocks, and little color, ornamentation, or natural light. These common prison architectural designs do not encourage positive individual or group experiences. Even recreation spaces are designed in this way—with little or no access to green spaces, often as covered cages, sometimes outdoors, but too often simply as another indoor space, such as a gymnasium. In Madrid v. Gomez—a case challenging the constitutionality of conditions at Pelican Bay State Prison in California—the court remarked that the sight of incarcerated people in the facility’s barren exercise pens created an image “hauntingly similar to that of caged felines pacing in a zoo.”

Ventilation in cells is poor, and often there is no heating or air-conditioning, which allows temperatures to reach deadly highs or lows. The summer months are particularly brutal in the South, where cells can reach triple-digit temperatures. One 2022 study of Texas facilities found that 14 inmates on average died due to heat-related causes each year between 2001 and 2019, whereas no heat-related deaths occurred in climate-controlled facilities. The United Nations Committee on Torture has called for the U.S. “to remedy any deficiencies concerning temperature, insufficient ventilation and humidity levels in prison cells,” but state budgets rarely cover such upgrades.

Prisons are overcrowded, and social distancing to prevent the spread of communicable diseases such as tuberculosis or COVID-19 is practically impossible. Mortality in prisons skyrocketed by 77 percent at the height of the coronavirus pandemic. In the early ’90s, the New York State prison system was the source of outbreaks of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis, which is as dangerous as the name implies. And when natural disasters happen, prisoners are left to the whims of corrections staff. In New Orleans during Hurricane Katrina in 2005, for example, guards abandoned one jail building for days, and some prisoners were not evacuated until days after the storm hit, when floodwaters had reached chest-level, according to Human Rights Watch. More recently, as Hurricanes Milton and Helene hit, prisoners were trapped in their cells without functioning utilities or plumbing in Florida and North Carolina.

Prisons are often located near environmentally hazardous sites. Rikers Island, for example, is “literally on top of a landfill.” Water and air quality are predictably poor in U.S. prisons, as is the food, which the American Civil Liberties Union has described as “often unpalatable and innutritious” as well as lacking in fresh fruits and vegetables. Instead, it is “high in salt, sugar, and refined carbohydrates” such as breads, cookies, and crackers. Prison diets are just the kind that exacerbate (or facilitate the onset of) chronic conditions like diabetes and high blood pressure.

Then there are the psychological aspects of being under constant supervision and control. Ram Subramanian of the Brennan Center for Justice writes:

Life in a U.S. prison is filled with an endless parade of security measures (caging, handcuffing, shackling, strip and cell searches, and lockdowns) punctuating a daily routine marked by enforced idleness, the ever-present risk of violence, often adversarial relationships with prison staff, and only sporadic opportunities for constructive activities offering rehabilitation, education, or treatment. Solitary confinement is often used as punishment for minor violations of prison rules, such as talking back, being out of place, or failure to obey an order. Incarcerated individuals in America live in a harsh, dystopian social world of values and rules, designed to control, isolate, disempower and erode one’s sense of autonomous self.

The daily deprivation and exploitation faced by prisoners is endless, and it’s worth dwelling on a few more examples. Solitary confinement is abhorrently widespread and causes lasting harm, both physical and mental. Mail is intercepted and sometimes scanned and sold back to the inmate by a for-profit company. Even hugging one’s visiting child can be off-limits. Phone calls and “commissary” items—everything from food to shampoo to over-the-counter medications—are extremely overpriced and unaffordable (prison labor, when paid, often provides pennies on the hour). In a nine-month investigation of prison commissaries this year, The Appeal found markups for everyday items to be as high as 600 percent (for a denture cup in Georgia). Peanut butter in Georgia was more than 70 percent marked up. In Missouri, ramen noodles and Tums were more than 65 percent marked up. In Virginia, a prisoner would have to work over 8 hours to earn enough to pay for a Ramadan greeting card. Some prisons also charge sales tax and fees besides taking out various deductions from pay such as “room and board.”

I mention all of these examples to counter a tendency in our culture to see prisons and imprisonment as just another normal part of our society. As Davis has written, “[T]he prison is considered an inevitable and permanent feature of our social lives, [...] so ‘natural’ that it is extremely hard to imagine life without it.” Citing the popularity of prisons as tourist attractions and the fact that so many prison films have been made, Davis notes that there is a “persisting fascination” with prisons. There’s also no shortage of TV shows about cops, investigators, lawyers, and judges—the people who help put other people in jail and prison. Last year I wrote about how prison writing in popular publications does political work to normalize what is actually an unacceptable cruelty: to put someone in a cell and subject them to isolation and violence, sometimes for years on end. As I put it, “It is all too easy to conflate the humanity of the people in the stories with the idea that our punishment system is acceptable.” We cannot forget that mass incarceration is part of a larger criminal punishment system that is rife with injustice. It is this system of jails and prisons—these bleak and punishing places that are unhealthy for both the body and spirit—into which we have chosen to put millions of people, at enormous cost to them, their families, their communities, and society as a whole.

The United States has the highest incarceration rate in the world and targets its most vulnerable citizens for imprisonment. It’s no surprise that imprisonment itself is considered a social determinant of health. For every year spent in prison, a person loses 2 years from their life expectancy. Even family members of incarcerated people lose 2.6 years of life compared to people who have not had a family member locked up. This makes sense when we think about how traumatic it is to be separated from a family member. More than half of women prisoners have children, and most were the primary caregivers before being locked up, meaning that kids are being punished simply for being their parents’ children.

As Marc Mauer traces in his 2006 book Race to Incarcerate, our current era of “mass incarceration” began in 1973, at which point the state and federal prison population began to dramatically increase. There were many forces at play: the War on Drugs, started by President Nixon and ramped up by President Reagan, New York’s Rockefeller Drug Laws (which imposed harsh sentences for possession of even small amounts of drugs, setting the tone for the nation’s criminal punishment going forward), the previous decades of deinstitutionalization (which left people with mental illness on the streets, where they were then picked up and put into jails and prisons), and the various drug epidemics (heroin in the 1960s, cocaine in the late ’70s, crack cocaine in the ’80s). The loss of traditional manufacturing jobs in the ’70s and ’80s and Clinton’s dramatic cuts to welfare in 1994 were also policies that left people without employment or government assistance. Thus, people were more prone to economic precarity and encounters with the criminal punishment system.

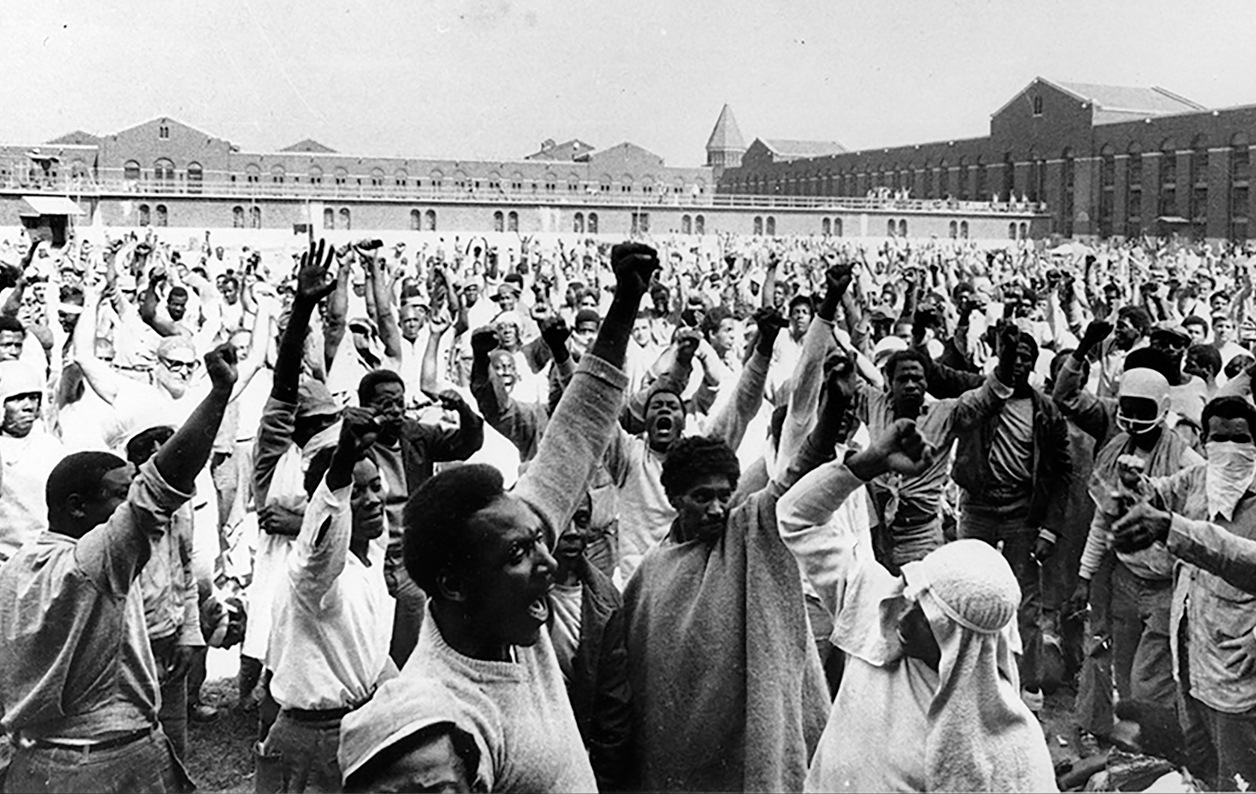

In the years before the rise of mass incarceration, prisoners began to protest the conditions of their confinement with urgency. In parallel with the social justice and civil rights movements of the 1960s and ’70s, people behind bars became more politically conscious and organized to demand better treatment. One of the key areas of protest was healthcare, which was a top concern of prisoners in the Attica Prison uprising of 1971 in New York. During this “prison rights movement” of the ’60s and ’70s, prisoners brought a slew of cases to court. As legal scholar Elaina Marx notes, it was a time of “judicial activism” in which many courts ruled in favor of prisoners’ rights for the first time. The courts enacted consent decrees, or court orders, under which prisons were required to make “reform in areas including housing conditions, security, medical care, mental healthcare, sanitation, nutrition, and exercise.” The judiciary insisted that prisons “provide (costly) medical care and reasonable housing.” What’s more, Marx writes, the courts were “directly supervising those improvements.”

Inmate uprising in the prison yard at Attica Prison (1971)

Inmate uprising in the prison yard at Attica Prison (1971)

Journalists and other experts, too, documented the sorry state of prison healthcare in the 1970s. In 1973, the English investigative journalist Jessica Mitford wrote Kind and Usual Punishment: The Prison Business, in which she details the sham of “rehabilitation” efforts in California prisons and the unethical practices of lucrative (for the researchers) medical research conducted on prisoners. From interviews with ex-prisoners, Mitford concluded that “medical treatment amounts to criminal neglect in many instances.” The confidential doctor-patient relationship, she noted, had been completely distorted, as files on inmates, which included psychiatric information, were available to prison officials and police agencies but not the inmate or their attorney.

In 1975, Seth B. Goldsmith, a professor of hospital administration at Columbia University, wrote Prison Health: Travesty of Justice, in which he outlined “terrible conditions” in jails and prison, a “barren wasteland of medical care.” The healthcare programs there, he concluded, were “obsolete, unsafe—in a word, unsatisfactory” and violated the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition on cruel and unusual punishment. Susan M. Reverby, a historian of American healthcare, noted in 2019 that a study from around the same time as Goldsmith’s 1975 book “concluded that modernization in the provision of health care had eluded prisons and jails. Such care was still stuck in the ‘horse-and-buggy’ era, this national report claimed, where the physician merely stopped by but could, or would, do very little.”

Goldsmith had also written a review of healthcare conditions at Orleans Parish Prison in New Orleans in 1973. At that time, he had been assigned by a court as a medical consultant to see how healthcare could be improved in light of a class action lawsuit brought by inmates (the court had found that conditions there violated the Eighth Amendment against cruel and unusual punishment). He documented what he called “abysmal medical conditions”: patients were shackled to hospital beds when taken to outside facilities for specialty care; dental care consisted mostly of inmate-requested tooth extractions performed once a week; medical records were sloppily kept, if at all; few basic resources (medical reference books, exam tables) existed; and psychiatric care was “essentially nonexistent” except to send the most serious cases to Charity Hospital, the local healthcare provider for the indigent.

Ultimately, Goldstein concluded in 1975 that his findings were not unexpected, as “the custodial goals of a jail-house conflict with the therapeutic goals of a medical department.” Sixteen years later, in 1991, physician and prisoner Alan Berkman would argue essentially the same thing. Berkman was a radical who had been active in the Weather Underground and Students for a Democratic Society and was convicted of armed robbery and possession of explosives, for which he served eight years in federal prison. He was diagnosed with Hodgkin lymphoma during his pretrial detainment and spent years struggling to obtain adequate healthcare in prison. He became an activist for the improvement of prison healthcare as well as the rights of people in the Global South with HIV and AIDS to obtain treatment. Berkman argued that “control rather than care [formed the underlying] medical rationale in prison health care” and that this “undermine[d] humane treatment of incarcerated people.”

Given the contradictory mandates of “control” versus “care,” it almost seems absurd to ask whether good healthcare can actually be offered in a modern U.S. jail or prison. In a nation that prides itself on consumer choice—especially in regards to “commodities” like healthcare—a prisoner is unable to choose their healthcare provider, and informed consent becomes less meaningful in an environment where a patient is coerced by the state to accept care on a “take-it-or-leave-it basis.”

Coercion has, of course, been a big part of the relationship between the medical profession and prisoners going back to the post-World War II era, when doctors exploited vulnerable prisoners to conduct medical research experiments on them rather than providing healthcare. In one particularly egregious case from 1971, described by Mitford in her book, medical researchers in Iowa fed five “volunteer” inmates an unpalatable liquid diet via a feeding tube in order to induce scurvy, or vitamin C deficiency. The participants developed anemia, joint pain, extremity swelling, hair loss, shortness of breath, and depression, among other symptoms; one man was so severely affected he almost couldn’t walk. The lead researcher admitted to Mitford that the symptoms of scurvy had already been documented by British clinicians, so the study was conducted merely to confirm what was known. Mitford concluded that the research had been “a senseless piece of savage cruelty.”

In her 2006 book Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present, Harriet A. Washington devotes an entire chapter to detailing coercive experiments on “caged subjects” that took place from the 1950s to ’70s. These experiments (on Black and white prisoners alike) involved everything from CIA “chemical-warfare tests” with mind-altering drugs to injecting people with “live human cancer cells” or transfusing them with large amounts of plasma (“very sloppily” done, causing some patients to die and others to contract hepatitis from tainted blood products). The “most risky and painful” experiments, though, were “reserved for African Americans.” Washington describes dermatological research carried out at Holmesburg Prison complex in Philadelphia between the 1950s and ’70s, mostly conducted on African American men by Dr. Albert M. Kligman on behalf of dozens of pharmaceutical and cosmetics companies including Johnson & Johnson, Merck, and DuPont. For “anywhere from ten to seven hundred dollars,” the men underwent exposure to a suspected carcinogen, their fingernails were biopsied, their backs were patch tested with various chemicals, and they were inoculated with foot fungus, syphilis, and gonorrhea, among other infectious agents. Three-fourths of the men at the prison, Washington notes, “were administered cosmetics, powders, and shampoos that caused baldness, extensive scarring, and permanent skin and nail injury.” Washington characterizes prison medical research in this period as overall “racially unbalanced, abusive, dangerous, and scientifically sloppy.” The experimentation there only stopped in 1974, the year after a congressional hearing on human experimentation brought to light testimony by former Holmsburg inmates.

Despite the overwhelming ethical problems with this research, Washington explains that prisoners generally wanted the opportunity to participate in research. Even though informed consent was shoddy at best—risks were downplayed if mentioned at all—and sometimes prisoners (who may have had low literacy) had to sign legal waivers absolving the researchers of responsibility for any harm that might occur, prisoners stood to benefit in several ways. They could earn money or get reprieve from “the hell of prison life.” But, most disturbingly, research participation was “often [an] inmate’s sole point of entry to medical care, which was sketchy.” Ultimately, Washington notes, such experimentation came about in the first place because of who the prisoners were: many were poor, uneducated members of “despised and powerless minority groups” that were “feared and hated.”

For historical context, recall that the 1947 Nuremberg Trials had convicted (and hanged) Nazi doctors for conducting horrific and cruel medical experiments on concentration camp prisoners, thus resulting in the Nuremberg Code that was supposed to guide medical experimentation and thus could have justified an end to experimentation on prisoners (a point noted by both Mitford and Washington). But as Mitford wrote, this had little effect in the U.S.—even though the American Medical Association and the World Medical Association had both issued guidance against prison research, with the latter describing prisoners as “captive groups” of persons who should not be used as research subjects. In 1979, the Belmont Report, issued by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, outlined guidance for research involving human volunteers, but it mostly rehashed the basic principles of bioethics (autonomy of the patient, beneficence on part of the clinician, non-maleficence or “do no harm,” and justice). The United States continues to allow prisoners to participate in medical research, but states have their own laws or restrictions in place as well.

As Washington points out, we can see how coercive relationships allow “research” to be conflated with “care or treatment.” This is eerily reminiscent of how Mitford described the sham of prisons as “rehabilitation” in the late 1960s and early 1970s. For a brief period at that time, prisons promised “rehabilitation as opposed to punishment, utilization of the latest scientific therapy techniques, classification of prisoners based on their performance in prison, [and] a chance for every offender to return to the community as soon as he is ready.” A key part of this system, Marc Mauer notes in Race to Incarcerate, was the indeterminate sentence. A prisoner could hope to “leave earlier if they were rehabilitated.” But “rehabilitation,” as Mitford describes it, was simply another way to mete out the sentence as a form of punishment, another form of control “disguised as treatment.”

Two doctors who work in carceral medicine, Rachael Bedard and Zachary Rosner, say that prison healthcare is, at best, harm reduction:

What does it mean to practice medicine in death-making institutions? Knowing that jails are fundamentally sites of harm, our work as physicians is best framed as harm reduction. Partly we try to prevent and mitigate the negative impact of illness in a population overburdened with health issues; partly we try to mitigate the negative impact of jail. At its best this means meeting people where they are to offer them sensitive, accessible health care. In some cases, patients get treatment they’ve long needed and long been denied in the community. We can diagnose and treat hepatitis C, for example, or take care of undermanaged high-blood pressure and diabetes. At its worst, though, the work is despairing. In these moments, it becomes bearing witness without being able to intervene effectively in the worst of what you see.

Much like healthcare for people who are not behind bars, prison healthcare is a patchwork system. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention noted in 2010 that it did not have national-level data on the healthcare carried out in state prisons. So the CDC conducted a first-ever survey, the National Survey on Prison Healthcare, published in 2016. This was a very basic look at things like medical conditions tested for on admission, specific services and specialties offered, and whether care was onsite or offsite, among other variables. A 2017 Pew Charitable Trusts report found large variation in state spending on healthcare per inmate per year. The state that spent the least (2015 figures) was Louisiana, at $2,173; the most was California, at nearly $20,000. (The 49-state median figure was $5,720.)

Louisiana and California stand out for other reasons. The former is home to Angola, the State Penitentiary located on a former plantation that’s one of the most notorious prisons in the country. There, a judge ruled in 2023 that the facility, over a period of 26 years, had demonstrated a “callous and wanton disregard” for the health of inmates, saying that “The finding is that the ‘care’ is not care at all but abhorrent cruel and unusual punishment that violates the Constitution.” This “medical mistreatment” had led to “unspeakable” human costs, the judge wrote. Just a few examples: one man experienced many months of delays in diagnosis and treatment for cancer and died. Another man made several requests for assessment of worsening back pain which were ignored; he became incontinent and eventually died, with an autopsy revealing he had a large tumor compressing his spinal cord. Yet another inmate complained of chest pain for 16 months; when he was evaluated, he was discovered to have cancer and died a week later. And in California, the state which boasts an incarceration rate higher than any democratic nation in the world, the Department of Corrections sterilized at least 250 women from the late 1990s until 2010 without obtaining proper agency approval, bringing back the kind of practices once thought relegated to the eugenics movement of the first half of the 20th century.

The Social Security Act of 1935 generally prohibits federal dollars from being used on prison healthcare, and it is politically unpopular, as one ethicist puts it, to spend money on people who have “violated society’s norms and rules.” So facilities have found a few ways to provide healthcare to inmates: they can run healthcare themselves, either under the Department of Corrections or with local health departments (New York, Louisiana); they can contract out with a university or other local healthcare system (Texas, Georgia, New Jersey, and Connecticut), or they can contract out to a for-profit corporation. In Harris County, Texas, which includes Houston, jail healthcare for some 9,600 inmates is administered by Harris Health, the county’s healthcare system for the indigent. Private, for-profit corporations that carry our corrections healthcare include Wellpath (owned by private equity), Corizon, and NaphCare. A Reuters study in 2020 found that 60 percent of the country’s top jails contract healthcare out to corporations, and the news agency’s analysis of 500 jails from 2016-2018 found a higher death rate among facilities that contracted out care compared to those run by government agencies. Wellpath, which claims it cares for 220,000 adult and juvenile “vulnerable patients in challenging clinical environments,” was the subject of a Senate investigation headed by Elizabeth Warren in 2023 which documented a number of disturbing findings: significant delays in care, blanket denials of care, inadequate staff, negligent care, failure to follow doctors’ orders and internal policies, cost-cutting measures, and inadequate mental health care including inappropriate use of restraints and solitary confinement. Senator Warren’s investigation concluded that “Nationwide, the privatization of prison health care has been associated with instances of reduced quality of care, higher death rates, and less transparency.” Reporting on the “jail health-care crisis” in the New Yorker in 2019, Steve Coll noted that the trend of privatization started in the Reagan era and continued into the ’90s, especially after Clinton’s 1994 crime bill, which caused significant growth in the prison population. Other for-profit providers, including NaphCare and Correctional Health Partners, have much to answer for as well.

Whatever agency is administering the healthcare, prisoners face a series of obstacles to obtaining care: administrative burdens to request care, copays, waiting, denials, worsening of symptoms, and the psychological distress of advocating for oneself while also staying in the good graces of people whose help you need. Because life in prison is so expensive, Cecille Joan Avila explained in Prism in 2022, prisoners often have to choose whether they will pay for healthcare, food, or other basic necessities. Avila found that in 2022, all federal prisons and 40 states required prisoner copays. Often, these are in the range of a few dollars. But again, taking into account the exploitatively low pay rates for prison labor, these copays are a hardship, sometimes taking up to a month’s pay to save. Much as they do outside of prisons, copays simply function as barriers to care. Consider the experience of Cynthia Alvarado, who served 12 years in Pennsylvania for a wrongful murder conviction:

"People struggle with not affording the copay.” [...] “That creates mental health issues ’cause now you’re depressed, now you’re sad, now you have more problems over not being able to afford something that should just be free while you’re in the custody of their care.” [...] Alvarado explained that to deal with her acid reflux or other ailments while she was incarcerated, it was $5 to make a sick call and then $5 for each medication needed to treat it. She could buy some medication at the commissary, like antihistamines, but it was often extremely expensive. The costs to treat any chronic conditions would quickly pile up. Eventually, she just learned to deal with the impacts on her health rather than risk a large amount of outstanding debt to be paid upon her release.

Luci Harrell, herself formerly incarcerated, wrote in 2022 in Scalawag about how unaffordable prison healthcare is, describing the experience of her friend, Vanessa Garrett:

On top of that, every visit required a $5 copay for being seen, plus a copay for each medication. [...] Of all Garrett's negligent prison health care experiences, one issue had the potential to be life-threatening. After several visits for unusual numbness she was experiencing in both legs in 2017, Garrett developed a growth on the side of one leg. Some nurses said it was a bug bite: $5. Others told her to lose some weight, ignoring her characteristic numbness and the fact that she was falling down whenever her toes would go to sleep because she simply could not walk. Another $5. “They were telling me I was just making it up, that it was in my head,” said Garrett. “But when they finally did the ultrasound, they found out it was a blood clot that had broken itself down.”

In a Washington Post op-ed earlier this year, Hope Corrigan described the ordeal of her ill 71-year-old father, who was sentenced to three years in prison for racketeering. At the time of his sentence, he had an autoimmune condition and a blood cancer that required careful management. She writes:

In many prisons, including my father’s, inmates must request health-care services through corrections officers who have no medical training, and who often decide whether an issue is worthy of medical care. This means that even minor and nonfatal health issues that aren’t life-threatening often result in needless suffering. We quickly learned how to thread a delicate needle: be advocates, loud enough that prison officials knew he had family watching and waiting, but not so loud that it seemed like we were asking for special treatment. In prison, the guards and nurses are in control. Be silent and your family member has no advocate. Push too hard and risk retaliation. “There is a constant and consistent fear that if you push too much, if you advocate too much, somehow there will be an equal and opposite force that harms your loved one,” Williams said.

These examples show not only the bureaucratic barriers to prison healthcare but the fact that power relations are always present and always, as Alan Berkman pointed out, undermine care.

Another serious problem faced by prisoners is their inability to challenge the conditions of their confinement. The “judicial activism” originating in the ’60s and ’70s was met with backlash from the conservative right, who saw it as evidence of prisoners’ unreasonable demands for special treatment. Citing cases involving prisoner complaints about melting ice cream, chunky versus smooth peanut butter, doctors implanting mind control devices into prisoners, and demands for gender-affirming healthcare, among others, lawmakers at the time talked disparagingly about “jailhouse lawyer antics” and the “crushing burden” of “frivolous lawsuits” which amounted to crimes against taxpayers. As a result, in 1996, a Republican Congress and Democratic President Bill Clinton passed into law the Prison Litigation Reform Act, which imposed practically insurmountable barriers to prisoners seeking to bring lawsuits against their facilities. Lawsuits plummeted as a result. The Act has prevented countless cases of mistreatment from being challenged and remains a major obstacle to the improvement of prison healthcare and prison conditions in general. As Elaina Marx noted, in 2003, Margo Schlanger of Harvard Law School reviewed inmate litigation in the years prior to and after the PLRA and found that lawsuits rose in proportion to the rise in inmate population and that prisoners had not actually been particularly frivolous in their lawsuits. It wouldn’t be the first time the right had made hyped-up claims in the name of law and order.

In 1957, the United Nations created the Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners, a legally nonbinding set of guidelines for member states based on the principles of international law. Revised and renamed the Nelson Mandela Rules in 2015, these are essentially best practices for prison operations worldwide. A major emphasis of the Rules is that prisoners must be treated as human beings who have inherent dignity and worth. One of the nine areas that was revised in 2015 was Medical and Health Services, which are considered the responsibility of the state and should be offered free of charge and in a timely manner at a level comparable to care in the wider community. There is also an absolute ban on torture or other ill treatment. Just based on these few examples, it’s fair to say that U.S. jails and prisons are violating the Mandela Rules on a daily basis. While the U.S. lacks national standards for prison healthcare (although there are voluntary accreditation programs, and President Biden recently signed into law an overhaul of federal prison oversight), because the Rules exist, there is simply no excuse for the U.S. to maintain such dismal healthcare within its criminal punishment system. In a 1972 analysis, two scholars at the NYU School of Law found that nearly all of the Attica prisoner demands, for instance, were consistent with the Rules. They concluded that “the prisoners demanded their putative rights as world citizens.”

In the U.S., we are used to politicians telling us that law and order will keep us safe. By this logic, keeping certain “bad” people in prisons will lead to public safety. But this isn’t true at all. Mass incarceration came about because of policy choices related to the way we criminalize people who are often poor and marginalized. Levels of what we call “crime” have gone up and down over the years even as imprisonment levels reached a peak in 2009. Even the Nelson Mandela Rules, as useful as they might seem, are predicated upon the idea that prisons are useful because they keep society members safe from crime. The U.N. document reads, “The ultimate purpose of imprisonment—the protection of society from crime—is undermined in prisons which are overstretched and poorly managed.” But we know that prisons do not stop crime—if anything, they actually increase future crime. And they are not rehabilitative.

Prison abolitionists Mariame Kaba and Andrea J. Ritchie argue that our concept of “safety” needs to be completely rethought:

Safety isn’t a commodity that can be manufactured and sold to us by the carceral state or private corporations. Nor is safety a static state of being. Safety is dependent on social relations and operates relative to conditions: We are more or less safe depending on our relationship to others and our access to the resources we need to survive.

A safe society is one in which people have the resources they need to survive and thrive, including healthcare, housing, food, education, a living wage, and a clean and healthy environment. A safe society is not one in which the poor and marginalized are targeted for arrest, locked up, and released often in worse condition than when they entered. A safe society is one in which reparation, not retribution, is the basis for justice after someone has committed a harm to another person and to society.

The immediate imperatives are those of police and prison abolition more generally: to reduce harm without legitimizing the criminal punishment system. We need to decrease people’s contact with the system and to decarcerate whenever possible. Beyond that, we need to repeal the PLRA, ensure that any Medicare for All legislation includes prisoners in its universal program, enable federal spending on prison healthcare, enact more robust public health policies, and continue the work of a leftist political project to create a society that truly meets people’s needs.

As Davis reminds us, prisons themselves are reforms. They were created as alternatives to corporal and capital punishment. But we know that the reform is too grotesque to be reformed. To truly address the crisis of healthcare in jails and prisons, we have to get rid of prisons entirely. They are “death-making institutions,” and we simply cannot expect to nurture life and health in something that is not designed for that purpose.