The Political Uses of Prison Writing

The New Yorker and the New York Times present “beautiful” stories of the human spirit in prisons. But why don’t we come away committed to ending the caging of human beings?

About The New Yorker: like many people, I subscribed for years and collected a large stack of the magazines on my bookshelves and in bins under my bed. Buying-but-not-reading the magazine was just a habit ingrained since my college days, when writing instructors fed me and my classmates a steady diet of the Adam Gopniks and Oliver Sackses of the world—with a sprinkling of the Jhumpa Lahiris, of course. The publication was, apparently, a kind of reference point for good narrative nonfiction writing: literary and polished and vaguely political but never radical (at least not to my budding leftist sensibilities). But I always found the magazine to be hit-or-miss. Hence the big stacks (way too many Trump covers) that went into the recycling bin after I kicked the subscribing habit back in 2019.

Recently, I came across imprisoned writer Joe Garcia’s New Yorker essay “Listening to Taylor Swift in Prison.” Garcia, who has served over a decade of a life sentence for murder (he says he’s guilty—I mention this because this probably makes him, for some readers, less deserving of sympathy) and is approaching the possibility of parole, recounts how he grew into a Swift fan as he moved throughout different facilities in California’s correctional system, meeting other men who were also, to his surprise, Swift fans. We learn about Garcia’s decades-long isolation not just from the outside world but from his partner. We learn about how prisoners get things (entertainment and other human necessities) in prison. The piece ends on an ambivalent note. How will Garcia answer the questions that come from his parole board? He doesn’t know. But he’s spending his days thinking about his life trajectory to the tune of Swift’s music along with the promise of seeing his former partner again one day.

Now, before even reading the piece, I was suspicious—not of the author or the subject matter but of this kind of essay’s use in a publication with decidedly liberal or even centrist tendencies. In the liberal way of telling stories, bad things happen to people, but they can tell stories to rise above victimhood, and we can become more human reading about them and the triumph of the human spirit in the most adverse of conditions. Sometimes, these people are even like us or remind us of ourselves. Often, these stories of crime and punishment are complicated, and the solution (if any is given at all) is presented as perhaps something in the middle of what radical leftists and right-wing conservatives want—remember, both sides have valid concerns and even hold common values. We all want what’s best for society. But, again, it’s complicated. Sometimes it’s best not to come down on one side or the other. Like all good writers, liberal publications tell us, we’ll show you, not tell you.

So my question was this: what work was Garcia’s piece doing in such a publication and for its readers?

Some of the responses on social media offered clues about the impact of the piece on readers (disregarding the occasional “you’re giving a voice to a murderer/what about the victims?” type responses):

- “Beautiful” – commonly used adjective to describe the piece.

- “Beautiful and evocative”

- “Lovely”

- “Made me cry”

- “Brought me to tears”

- “Incredible essay”

- “Calmly devastating”

- “Joyful/heartbreaking”

- “Openly wept”

- “A reminder that everyone has humanity and potential for rehabilitation”

Readers who responded online were clearly struck by Garcia’s storytelling, his interpersonal loss (his partner) and loss of freedom, and his ambivalence about redemption. Garcia writes for the Prison Journalism Project and has published in other major outlets. None of these facts are objectionable to me, and I fully support the journalism of people who are imprisoned. And, obviously, readers have a right to enjoy whatever writing they please.

My concern was how the piece was situated editorially—as just another essay by just another writer, the prisoner-as-published-writer. And my fear is that this type of piece in a liberal political publication actually reinforces the acceptability of evil: putting people in cages and subjecting them to isolation and violence.

There are many good reasons for prisoners to be writers and journalists (in addition to their own personal aspirations). Prisons and jails are notorious for lack of transparency and availability to journalists trying to cover them, and there are notable media biases in how crime, punishment, and prisons and the imprisoned are covered (the tendency is to dehumanize prisoners). Mainstream media often favors conservative “tough on crime” narratives, as pointed out by Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting and former public defender and “copaganda” media critic Alec Karakatsanis. (Just days ago, Senator Mitch McConnell repeated a common false trope about “soft on crime radicalism” being responsible for violent crime in U.S. cities.)

As explained on NPR recently, prison-run newspapers came about in the early 1800s, and the number of them has increased in recent years. There are programs like the Prison Journalism Project, which promotes “independent journalism by the incarcerated” and says it aims to bring “transparency to the world of mass incarceration from the inside and train[ing] incarcerated writers to be journalists, so they can participate in the dialogue about criminal legal reform.”

There’s also been an increasing amount of information available to us about mass incarceration over the last few decades. There are dozens of books about prison and mass incarceration, some written by scholars and others by people who are or have been imprisoned (read about the firsthand experience of Florida prisoner Shawn R. Griffith). Some works are even featured in the mainstream. Oprah’s Book Club has featured work by imprisoned writer Jarvis Jay Masters, who has been on death row in San Quentin State Prison for over 40 years for a crime he says he didn’t commit. Reginald Dwayne Betts, a poet, lawyer, and memoirist who was imprisoned for several years starting as a teenager, was in 2021 named a MacArthur Foundation Fellow (see a 2016 Current Affairs interview with him).

Amid this relative transparency (or at least the inclusion of mass incarceration as a subject matter in popular discussion) and some debate that occasionally smolders over the “defund the police” cries of 2020 (no, we didn’t defund the police, and yes, we should), we still have a horrible and unacceptable situation on our hands: the nation’s prisons and jails are as brutal, inhumane, and deadly as ever (and the criminal punishment system that feeds into these facilities is rife with injustice):

- The use of solitary confinement is widespread, as is violence and corruption.

- Countless prisoners have died during COVID, and hundreds of people have died in non-air-conditioned prisons during recent heat waves—or due to lack of basic medical care.

- Children are not spared from this violence, and their entry into the punishment system portends poor outcomes later in life.

- Some states are building even more facilities (despite pushback from local residents).

All of these points bear repeating, but they’re not the kind of details you tend to get from essays or “think pieces” in liberal media.

Consider the New York Times. In the week prior to this writing, I made a daily search of their website using the term “prison.” Most of the hits that came up were stories pertaining to inmate escapes in Pennsylvania or London. I ran the search on September 12, for instance, and the top eight hits were all about inmate escapes. The ninth hit was about a hunger strike in a Bahrain prison, and the tenth was about something else—no, wait, it was actually about the “Pennsylvania fugitive” whose mother says he has been “trained for survival.” (The term “superpredator” comes to my mind here.) You get the point. Nine out of 10 “prison” stories pertained to nail-biting manhunts of dangerous fugitives. With a preponderance of this kind of story, how likely are readers to be primed to question anything about the criminal punishment system?

Karakatsanis has pointed out how the content of the bulk of news stories about crime and punishment shapes our way of thinking about these issues. He asks why some stories get covered repeatedly and others don’t:

Why are some issues easily conceptualized as a single news story—“the debtors’ prison story”—while other stories are seen as continuously plentiful sources of daily news to be covered from the same and different angles each night, such as the “surge in shoplifting”? … One of the most overlooked aspects of contemporary news analysis is an examination of how the sheer volume of certain news stories distorts our understanding of what is important.

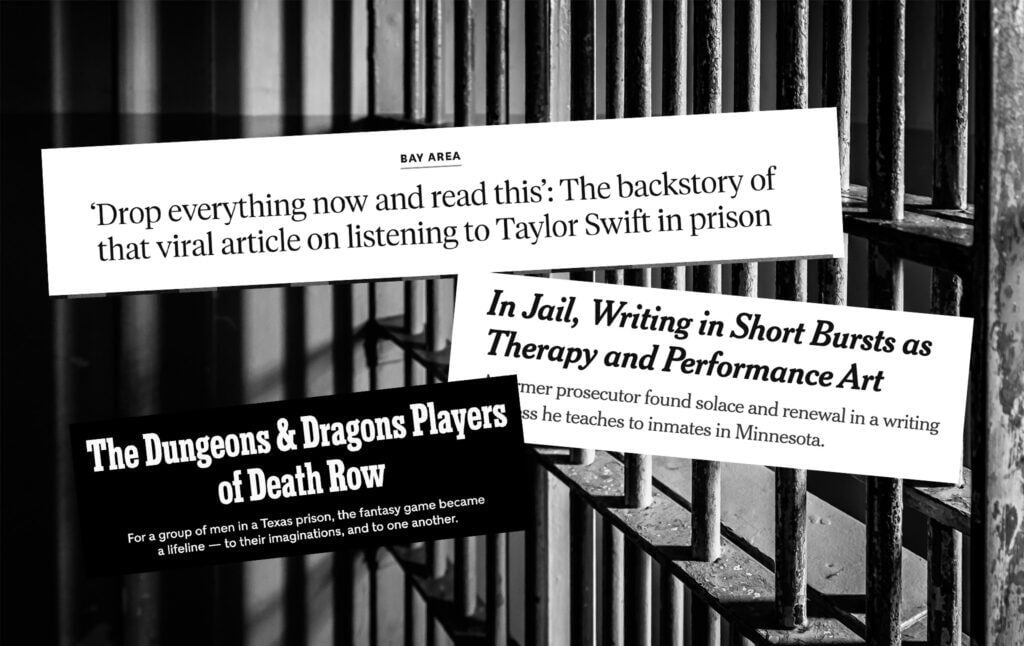

Keeping this in mind, I found it interesting that around the time of the Garcia’s New Yorker essay, the Times published two similar human interest stories: on Aug. 31, “The Dungeons & Dragons Players of Death Row” and on Sept. 6, “In Jail, Writing in Short Bursts as Therapy and Performance Art.” In these stories, prisoners do things just like people who aren’t behind bars. They play games in order to pass the time, to stimulate themselves intellectually, and to bond socially with others. They write to work out their past traumas as a form of therapy, which the jail system clearly won’t provide them. If, for a moment, you disregard the logistical difficulties of obtaining basic necessities in prisons (much less parts and supplies for complex games) or the overall rarity of educational enrichment in jail facilities, you have to concede that the stories are pretty mundane. Prisoners are just doing normal things. They are human. That we need reminding of these facts ought to disturb us.1

A much more important point, though, is that the humanity of the prisoners in any of these stories is separate from the fact that we as a society have chosen to inflict cruelty upon them by caging them. That’s the bigger story here. But if readers are too busy wiping misty eyes at how beautiful or heartbreaking the stories are and how much they, too, like Taylor Swift’s music and Dungeons & Dragons—or how some escaped predator is on the prowl (NPR had that one covered: “There are several manhunts underway this week: but don’t panic,” they advised.)—are they going to see the difference?

It is all too easy to conflate the humanity of the people in the stories with the idea that our punishment system is acceptable. It’s one thing to see people’s humanity as a reason not to cage them or otherwise inflict cruelty upon them. It’s quite another to see their humanity and still think caging them is okay.

Another work to consider is a cartoon in the New Yorker’s “Culture Desk” by an illustrator who works in the Rikers library system. It’s called “The Diary of a Rikers Island Library Worker” by Medar de la Cruz and came out in May of this year. The author recounts distributing books to people in different parts of the jail and how appreciative they are to receive them. He notes that many inmates are there simply because they “can’t afford” to post bail. The piece doesn’t note that the U.S. is a world outlier in its use of cash bail. But de la Cruz does mention how creative many of the inmates are and how he hopes he makes a “small difference” in their lives. The piece ends on something of a cliché: “At least you get to go home,” one person had told him.

Now, to be fair, the New Yorker has covered Rikers (including a 2014 piece about Kalief Browder, a teenager who was accused of stealing a backpack but maintained his innocence and spent hundreds of days in solitary confinement before eventually being released and later committing suicide.) But does the cartoon challenge in any way the underlying logic of mass incarceration? Why are we doing this to people? Could we close Rikers? Are people trying to close Rikers? Does this piece actually help people to think critically about imprisonment? I don’t think it does. What’s worse, it could actually be harmful. A piece like this can have the effect of normalizing the cruelty of a place like Rikers—it is, after all, just another part of our “culture”—and this is dangerous. If imprisoning people is seen as just another unfortunate occurrence, why question it?

As I was cleaning out a bunch of old magazines from under my bed recently, I happened upon a 2016 issue of Harper’s. “Rebecca Solnit visits death row,” the cover read. Her piece was called “Bird in a Cage.” It’s a first-person literary type of reflection on Solnit’s visit with a prisoner she befriended, one Jarvis Jay Masters—mentioned earlier—a Buddhist and a writer on death row. It opens and closes with reflections on Solnit rowing in the San Francisco Bay, a kind of meditation on freedom. In the middle of the piece, she tells us that Masters maintains his innocence, adding that the evidence is on his side. She narrates how he came to be imprisoned, how his case was appealed starting in 2001 (per his website, he is still waiting on a federal court decision), racial disparities in sentencing, and the logistics of getting inside the prison to visit Masters. If there’s some place in the piece where we as readers are given a chance to question any of what has gone on, it seems to be at the ending. Instead, we get workshopped sentences and not many specifics:

I want to keep rowing, to keep relishing that freedom on the open water under the changing weather, going with and against the tides, but I don’t need so much freedom that I can’t go inside a prison on occasion. Buddhism calls for the liberation of all beings, and it’s a useful set of tools for thinking about prisons and what we do with our freedoms.

We are all rowing past one another, and it behooves us to know how the tides move and who’s being floated along and who’s being dragged down and who might not even be allowed in the water.

Clearly the rowing and the tide is being used as a metaphor for systemic injustice and oppression (and even racism), but we’re not told who’s doing the injustice or who’s on the receiving end of the oppression. Who is meant by “we” and “our freedoms”? No time for an answer. Solnit then goes back to the scene at the prison. She recounts telling Masters that she was going to have some tacos later, after their visit, and he responds, “That’s freedom.” She writes,

He was right. Freedom to eat tacos on my own schedule, to pursue the maximum freedom of rowing, to enter the labyrinth of San Quentin and leave a couple of hours later, to listen to stories and to tell them, to try to figure out which stories might free us.

It was stories written by Masters and others, she says, that “made me care about him and think about him and talk to him and visit him. And it was these stories that made me hope to see him leave that cage on his own wings.”

Again—all beautiful prose, all unobjectionable ideas: life’s not fair, some people are free, others aren’t, and the writer has the luxury of mulling over it all (and she hopes Masters gets out). But the purpose here seems suspect. The passage is about thinking, not doing; knowing, not acting. Our responsibility as readers ends at a metaphorical awareness of the problem; there is no moral demand to solve it. Do we now feel we are aware of the problem of innocent people being sentenced to death? What about the ones who aren’t innocent? I’m reminded of how Karakatsanis characterized liberal “think pieces”: “these articles are therefore like fentanyl for well-educated liberals. It’s like pumping a drug into their veins that gives them the momentary bliss of thinking that we don’t need structural changes to make our society more equal.”

I’m not saying that literary writing can’t be political or tackle subjects like mass incarceration, the cruelty of imprisonment, or racial injustice (or that such writing can’t politicize individual readers). Works from writers like Toni Morrison, Ta-Nehisi Coates, or Colson Whitehead are just a few that come to mind in this regard. But the cruelty we as a society inflict upon people behind bars should not be so softly rendered in the political magazine medium.

What kinds of stories are we telling ourselves about prisoners and prisons in order to live with mass incarceration? When I picture Garcia listening to Swift or Masters meditating in his cell, all I can think is: we did this to them. We didn’t have to do this to them.

To really grapple with the urgency of the crisis of imprisonment, to build a movement in which we imagine other ways of addressing societal harm, we need to get past the stories we’ve been told. This is the work of prison abolition.

Just a few days ago, the San Francisco Chronicle published “the backstory of that viral article on listening to Taylor Swift in prison.” The article details the 9-month writing process of Garcia as he endured, at one point, “the Hole” (aka solitary) in San Quentin. Toward the end of the piece, the author writes,

Gross [The New Yorker editor] added that the success of the piece has gotten him thinking about how to get more people to care about examinations of the prison system. If an incarceration story doesn’t have Taylor Swift in it, how do you sustain readers’ attention?

Sustain readers’ attention? The media already has people’s attention.

Personal stories—and our methods of telling them—have their limits as political tools in our struggles for radical change. But this is not the primary problem. The problem here is a challenge for readers: we need to offer more than tears or sympathy to prisoners; we need to commit to seeing them as political subjects who require our political solidarity. When the preponderance of news and media stories about imprisonment or prisoners push the need for more punishment, make us feel fear, or make us feel good without helping us question the underlying logic of mass incarceration, we’re not moving forward as a society. We’re just collecting stories somewhere in our head and moving on to the next one while absolving ourselves of responsibility to care too much.

It’s also notable that it took the author of the Dungeons & Dragons story years to piece the story together from interviews and written correspondence with inmates—again, testament to how difficult it is for journalists to do this kind of work. ↩