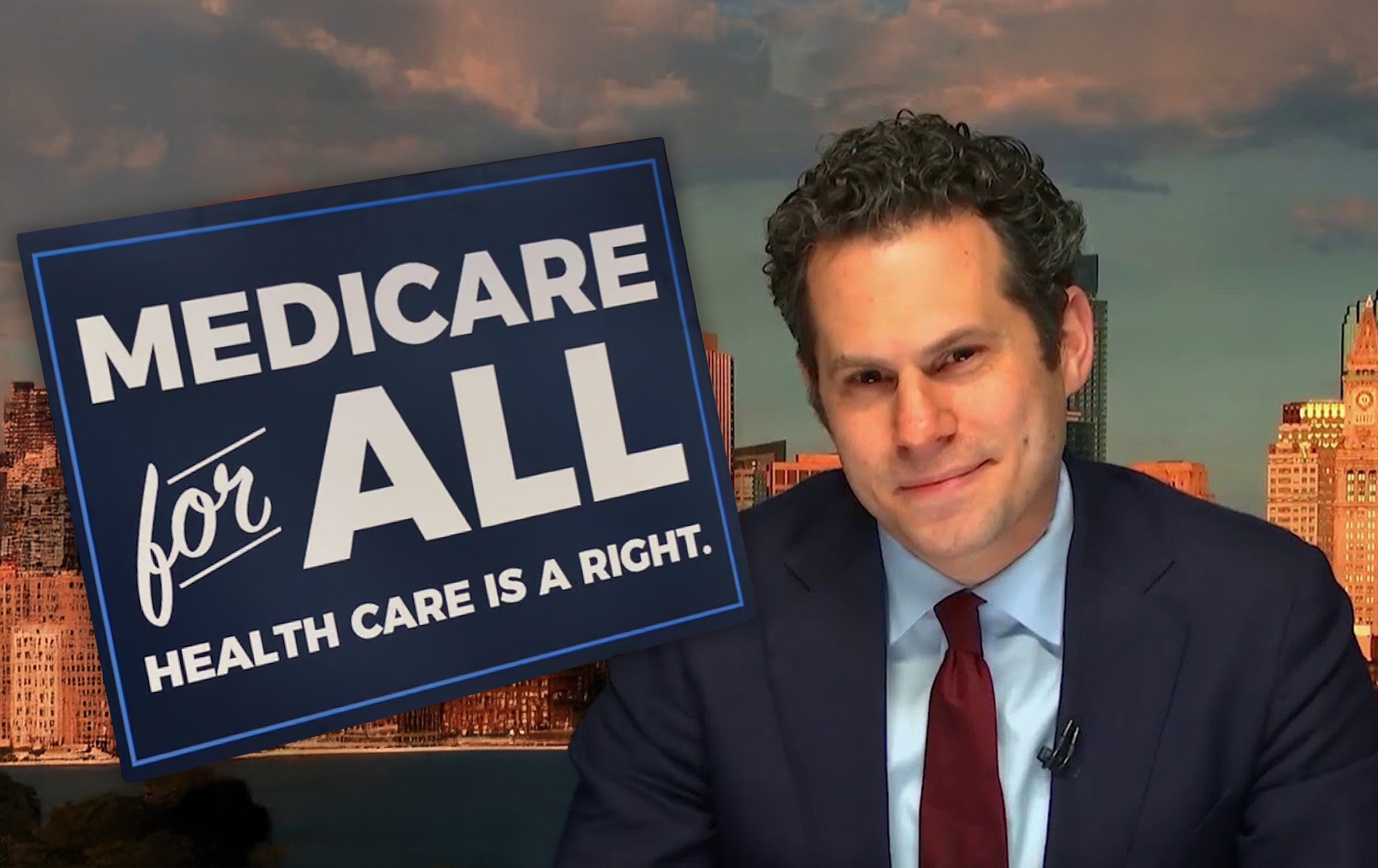

Why Did We Stop Talking About Medicare For All?

Medicare for All has seemingly dropped out of the political conversation. Dr. Adam Gaffney, a physician and Medicare for All expert, explains why we still need a single-payer healthcare system and addresses misleading talking points that are often made against it.

Dr. Adam Gaffney is the former head of Physicians For a National Health Program, an assistant professor at Harvard Medical School, and the author of the book To Heal Humankind: The Right to Health in History. Adam is one of the most articulate and effective champions of Medicare For All, having once fought five Fox Business Channel commentators at once. Today he joins to discuss why Medicare For All is still the best way we can improve people's healthcare. He responds to common objections, and Nathan challenges him with quotes from the author of the book The False Promise of Single-Payer Health Care. Adam shows why the objections are silly and why we need to build a consensus around the necessity of a single-payer plan.

Nathan J. Robinson

Listen, people are finally talking about healthcare again because someone shot the CEO of an insurance company. It would have been nice if it didn't take someone shooting the CEO of an insurance company for people to talk about healthcare again, but it happened, and now we are. Some people might be surprised. Maybe the people who worked at UnitedHealthcare were surprised that when their CEO got shot, the dominant reaction among many people was not deep sympathy but rather, I couldn't really care less if the head of one of those companies dies (insert “bad experience with your health insurance company”). Tell us a bit about the pent-up feelings about healthcare in this country—feelings that have been quieted since the healthcare discussion around the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and since Bernie Sanders was talking about Medicare for All. It has gone off the table and slipped from the discourse. What have we let slip from the discourse that is now coming out?

Adam Gaffney

Well, Nathan, you're right. Medicare for All was being very widely discussed. It was in the news all the time. There was growing familiarity and popularity with it, and it was really the center point of the two Democratic primary campaigns in 2016 and 2020, and it did get put on the back burner, I think, because of two things. One, those primaries ended, and two, the COVID pandemic, which ironically, strangely, and unfortunately, brought other issues to the fore around some of the public health aspects of the pandemic, even though I do think that Medicare for All would have made facing the pandemic better in many ways.

Look, we still have well more than 20 million people uninsured in this country. We have over 40 million people under-insured. We have medical debt, medical bankruptcies, and high out-of-pocket costs. We have people going without needed care for long periods of time and their health worsening as a result. We have premature deaths. We have all of these things. And one of the things that makes this such a salient issue is that it really does affect almost everyone. Even if you're young and healthy, at some point, you're going to develop medical problems and disabilities and need care. And if you don't, you have family members and loved ones and friends who are interacting with you and who need healthcare. It's just part of being alive. It's truly a universal issue. It's one that affects all of us. And its absence [from the discourse] was the odder thing, and so its return is sort of expected. This was going to be another major policy and political issue. It's going to remain, I think, in the center of our healthcare discussion, particularly as the Trump administration enters the fray.

Robinson

Now, I thought we were supposed to have solved this. There was a piece of legislation 10-plus years ago, famously called the Affordable Care Act, which passed. It was signed into law and should have made healthcare affordable. Healthcare is not affordable. What happened? What went wrong? You are a prominent advocate for a full single-payer system. To what extent did the Affordable Care Act, in fact, make healthcare more affordable, and why did it fail to solve the problem of making healthcare affordable that it set out to address?

Gaffney

When we say affordability, we mean two different things. They're both important, but they're actually somewhat separate. Affordability can mean what we spend as a nation collectively on healthcare: the total resources allocated to healthcare, either in dollar terms or as a percentage of our economy. And that's an important question, but let's put that aside for one second. The second part of affordability is, can I afford to get the care I need, and when I get care, am I being punished? Is there a tax on sickness, as people refer to it? Am I paying co-pays and co-insurance or even [more money] because I'm not insured? People think of those as the same, but they're actually very different.

When we say that in Canada, if you're hospitalized, it is free, or doctor care is free, that's because they have universal coverage first-dollar, meaning it covers everything, and they have eliminated these co-payments and deductibles and other out-of-pocket payments that I do believe constitute a tax on sickness. You're being punished for being sick, effectively.

Okay, so let's analyze both. So, you can have a very inexpensive healthcare system, meaning a poor country might actually not spend much money at all on healthcare, yet people can't afford to get it, and they're paying high out-of-pocket relative to their income because there isn't universal health coverage. You can have our system and spend what we do as a nation on healthcare but give everyone first-dollar universal access to all necessary care. And when we say that's an expensive system or not, it's sort of a philosophical question. Anyway, that's a bit of a divergence from what you're asking.

What did the Affordable Care Act do that was good, and what did it leave undone? What it did that was very good was to give people health coverage who didn't have it previously. So, it ramped up Medicaid, which is the public program for low-income people that was first passed by Congress in 1965. It expanded that to sort of all low-income adults, and that was narrowed by the Supreme Court, but that brought health coverage to about 20 million people who otherwise would be uninsured, and that made a difference. It also gave some subsidies for people with middle incomes to be able to buy private insurance, and those were good. What it didn't do was fundamentally change the private insurance-based nature of our healthcare system, which means that there still are well more than 20 million uninsured.

It didn't eliminate or even reduce, really, the co-payments and co-insurance and deductibles that people pay—even those who get their healthcare through their employer, which is most people with private health coverage. And it didn't deal with the fact that, as Matthew Bruenig and others have pointed out, it's not just how many people are uninsured at this moment today; it's how many of us will see lapses in coverage over the course of our life. That's a much higher number.

Massachusetts has a very low uninsured rate, but lots of people come in and out of coverage. When you fall into those lapses and happen to need hospitalization, you could be in huge trouble. You could go bankrupt because you're facing a giant bill. You could go out of network and not even realize it and get faced with a giant bill. So, it's a little bit of a long-winded response to your question, but what it did do is expand Medicaid, which is good. It lowered the uninsured rate incrementally, but it didn't fundamentally change the nature of the system, which leaves so many people out and which leaves all of us liable for potentially ruinous costs.

Robinson

If we add up the total average cost that people are paying for healthcare, obviously, there are a lot of different costs. You mentioned that the uninsured rate has gone down since the Affordable Care Act. In fact, I remember going to a presentation where someone was touting the success of the Affordable Care Act, and they really emphasized the decrease in the rate of uninsured people. And all I could think over and over was, but my insurance seems to suck, so how much better am I for being insured? I don't know. I feel like I'm actually getting ripped off almost more for having insurance. There are many years when I'm like, well, I wish I'd just not paid for insurance this year.

What do we know about the trends? When you add up everything people are paying for their monthly insurance, co-pays, and deductibles, has it gone up? How much is it? What kind of deal are people getting overall, whether they're insured or not? Because you can be insured and be getting a crappy deal.

Gaffney

Yes, and this goes back to the point I was making earlier about what you're exposed to and what we spend as a nation on healthcare. What we know is that people are spending more and more out of pocket for their healthcare. There was a time when people who got insured through their employer typically had no deductible. That time is over. Now, most do. Deductibles are running up to the thousands of dollars. Unaffordable Care Act plans can be sky-high. And so that's part of a broader and longer process of what we refer to as cost sharing, which is imposing these out-of-pocket payments on people. And that, actually, really goes back to this idea from economists.

I guess it really started in the 1970s, when it got popular, this idea of so-called moral hazard, that you needed to have out-of-pocket exposure to healthcare. Otherwise, you would over utilize, overuse it, and [the idea was that] that was what was driving up healthcare [costs]. And for decades, that was a central paradigm to health policy. “Skin in the game”—they dropped that term because it, rightly, kind of invokes a visceral-like anger of the people. But that was a reigning paradigm.

Now the health economists are starting to recognize that it was a failed paradigm, and, in fact, two very prominent ones that we reviewed in the book admit that it doesn't make sense, but that's part of a larger process. I don't think you can blame that on the Affordable Care Act, but you can say the Affordable Care Act didn't fix the problem, if that makes sense.

Robinson

You mentioned there the idea that basically, there need to be out-of-pocket costs. The economist way of thinking is, you need to price things so that people will weigh how much they really need them. With healthcare, the idea is, well, if healthcare were free, there would be no incentive not to overuse it, and because there's a limited supply, ultimately it has to be rationed somehow. So, when you impose costs, you are causing people to make rational decisions. And, of course, that is consistent with one of the animating ideas of the Affordable Care Act, which is that if you have a marketplace, the consumer will rationally make the decision that is best for them. That's kind of how it's pitched, and it's one of the arguments against single payer: we want you, the consumer, to be empowered to choose the healthcare that is best for you.

Now, I happen to hate the ACA marketplace. When I went on it to try and find an insurance plan—in fact, I wrote an article about the experience where I actually think I proved successfully that it is literally impossible to rationally compare the plans because insufficient information is available. But there is this broader idea that a market-based healthcare system makes sense because the consumer is in the best position to think about how much they want to pay. Talk a little bit more about this economistic way of thinking.

Gaffney

Well, there are two sides of it. There's the “moral hazard cost sharing,” which again, we'll talk about, and then there's the “choose the plan that best works for you.” And they're obviously very similar because they're both effectively market-based concepts of how to optimize the system through “rational market incentives.” But they have slightly different flavors. So, let's go back to moral hazard for a second. It goes way back to when Blue Cross first originated. Not to go too far back, but it was actually a nonprofit and didn't have deductibles. When commercial insurers started to enter the fray in the 1950s, they thought that people would just go to the doctor willy-nilly, and they called them sniffle claims. They wanted to put an end to that and create disincentives, so they created these payments. And then economists entered the fray in the neoliberal era and turned this business contrivance into an operating philosophy of healthcare. In fact, Martin Feldstein wrote this piece where he actually argued in the 1970s that the problem with American healthcare is we were over-insured—he used the phrase over-insured, which I think most people would find very funny—and that was an animating logic that led to a lot of things, and it did infuse the Affordable Care Act. You may recall something called the Cadillac healthcare plan tax that never actually got imposed, but it was part of the Affordable Care Act, and it was going to be a tax on these theoretically Cadillac, overly luxurious, typically union-based, healthcare plans. And by Cadillac, they didn't mean that you were getting flown out to Switzerland for thermal baths and getting luxurious suites at the top hospitals. It just meant all your care was covered. So, this was a very big animating logic, including by the time the Affordable Care Act was being discussed among the leading lights of health policy.

I just want to reiterate, it is wrong. First of all, people don't use healthcare they don't need. Almost definitionally, they may get healthcare they don't need, but they don't seek out healthcare they don't need. No one wants to go under the knife or take a pill or—

Robinson

It’s unpleasant. You don't go to the doctor for fun.

Gaffney

Lose their whole afternoon if they don't have to. There is waste, and there is unnecessary care, but it's not coming because people are like, I just want this unnecessary surgery. That's so rare, it's effectively negligible and doesn't need to be discussed. Many countries have free healthcare at the point of use. And what happens when you impose costs, when you make people pay out of pocket? What does it do? It rations care based on economic means. There's still the same amount of care being applied to society, it's just that it gets divvied out to people who can afford it rather than people who necessarily need it the most. It's means-based care delivery. So that's one thing, and that's been a big part in that, and that was parts of the ACA.

What you're talking about is this idea of choosing the plan that suits your needs. This is bunk. What does that actually mean? Well, first of all, that defeats the point of insurance. The point of insurance is that you don't know what's going to happen, so you want to be protected without knowing the future. If you knew you were never going to get sick, then, sure, don't even get insurance. Why bother? So, it puts you in this ridiculous position of being like, well, what are the odds you are going to get sick? What are the odds you will be hospitalized? If I knew that I was going to get sick, then I'd want the most generous plan. But that defeats the whole point of social solidarity and of having a universal system that covers you regardless of what happens.

Robinson

It's asking you the question, how much do you expect the unexpected to happen this year? Well, I don't know because it's the unexpected.

Gaffney

The point of this is that I don't have to make ridiculous predictions that I can't actually make. That is the nature of nature. We don't know what's going to happen to our bodies, and we all will get sick. So it is truly very silly to have a system where we force people into the position of making these decisions where there's no good answer. I'm a health policy person, I don't really know what the right advice is to give on an individual level to people because it really is all contingent on the future.

Robinson

I was looking at these broad silver and gold plans on the ACA marketplace, and gold suggests that it's a better plan, but it's actually just a higher premium plan with a lower deductible. So it actually might be a worse plan if I don't use it—if I don't get sick, then it's a worse plan because it's just taken more of my money. Gold suggests good, but it's not necessarily good. And I was like, what is the correct balance here? And the answer is, well, I don't really know. I can't really afford more than $500 a month, so I'm going to get one—

Gaffney

Get the one that makes sense. And that will mean a higher deductible, and if something happens, you could be in a bad spot. And I want to say also, in addition to imposing these kinds of cost sharing on people—again, what people call a tax on sickness—it also doesn't make sense to finance healthcare through regressive premiums. Now, the Affordable Care Act marketplace does include subsidies depending upon one's income, but at the end of the day, we should pay into the system according to our means, rather than a sort of standard dollar amount that applies to people regardless of their income, which is how it is financed to some extent, particularly in the employer sponsor coverage arena. That's a regressive way to finance healthcare.

And so when you think about healthcare financing, both in terms of the question of access but also the question of fairness in terms of contributions and as a general kind of sentiment and philosophy, how should it be run? It should be that we contribute based on our means, and we get care based on our needs. That's how it should be run. When you have co-pays, when you have sort of head tax style premiums, [...] it's actually regressive because you're actually paying more if you get sick. It should be the opposite, because when you're sick, you often have less income. And so, there's a real sort of upside-down nature to the whole way that it's constructed.

Robinson

It creates bad incentive. You mentioned that people don't usually seek care that they don't need. I have found myself, because of the costs, making what I think of as bad decisions from the perspective of my own health, like my decision to not go to the doctor because it's going to cost too much money. People beg not to be put in an ambulance. From the perspective of health, you don't want people begging not to be put in an ambulance. That's a bad decision. There was just this op-ed in the New York Times by a doctor who basically admitted that she misled patients—telling them that their insurance would probably cover something when she didn't really know if it would—because the thing was so important for them to get. Her patients were like, no, I can't get it because it's going to cost too much money, and she was like, well, this will save your life, and you need to do it. And they’d say, but will my insurance cover it? And she’d say, probably, but she didn't actually know, which I think is a little unethical. But she's writing about a situation where people are doing things that are objectively bad for their health because of this thing that is supposed to be helping them make more rational decisions by doing a cost benefit analysis.

Gaffney

So, a few of responses. First, the physician perspective on this issue, and then, more importantly, from a patient perspective. So from the physician perspective, and I haven't read the article, but think about how tricky this is for a second. You want to practice medicine and treat everyone the same and give the optimal care to everyone, regardless of whether they're high, middle, low income, or by their race and ethnicity—everything. That is the overlying philosophical premise of medicine. So, sometimes you'll hear people say, well, you should really take into account a patient’s means. Can they afford this care? And you can't ignore that. I agree, but look at the impossible situation we're talking about now. If you ignore those issues, you're potentially saddling your patient with costs they can't afford, which is terrible, and that obviously isn't okay. However, if you start deciding what care to prescribe based on whether someone's rich or poor, think about where that leads you. It leads you to class-based medicine. It's like, I'll give this guy the best drug for this, and this guy can't really afford it, so I'll give him crap. It's really bad. Obviously, I'm not suggesting that. As a physician, you can ignore the patient's actual ability to get the care you're recommending. Of course not. But the alternative is also really grim. You're making your decisions, and you're giving suboptimal or optimal care depending upon someone's class, effectively, and that's bad. We shouldn't be in that position.

So, to go back to your other point, from the patient's point of view, what you're saying is common sense. If you have a high deductible, you're going to avoid getting care you need when you need it because you have other expenses, and your resources are limited. For a long time, there was this debate whether that was actually harming people. And you may have heard of the RAND health insurance experiment. It's sometimes described as the largest social experiment ever performed. It was in the late 1970s, and they randomized many families to free care or high deductible plans. Anyway, that kind of gave this misleading sense that these co-payments and cost sharing were harmless, even though in that trial, there were signals of harm. But the point is, since then, there has been study after study showing that these payments do, in fact, harm people's health.

Just to give a few statistics, a study of being pushed into a high deductible healthcare plan for women with breast cancer found that it made them delay getting things like biopsies or even starting chemotherapy. Studies in people with diabetes have found that it causes them to put off needed cardiovascular care. A recent study found that even small co-payments cause Medicare patients to not take medications they need, and actually that led to higher deaths. It actually kills people. So, it's common sense to me as a doctor. I think it's common sense to a lot of people from their experiences, but it's taken the field a while to catch up and realize that people are dying because of these payments. It's common sense, and we need to change it.

Robinson

Well, a lot of what we've been discussing there is the case for healthcare that's free at the point of service. There's another aspect to this, which is that you could have co-pays and deductibles in a government run system. A lot of the discussion after the UnitedHealth killing has been around having corporations play such an important part in deciding who gets care and the bad incentives that arise from having a company that does better when it figures out ways to deny people care. So maybe you could talk about why that part of the system is so pernicious.

Gaffney

I think the best clear-cut case of the phenomenon you're describing is in the Medicare system. So you're familiar with Medicare.

Robinson

That's the good part.

Gaffney

But listen for a second, it's about to get bad. The Great Society Program passed in 1965 initially for the elderly, and now it also covers some disabled people as well as people with advanced kidney disease. Okay, so it's a public program. What happens over time is there is this idea of, well, let's say we bring in the private insurers, maybe they'll do a better job of keeping costs down of Medicare. And in 2003, this gets introduced as something called Medicare Advantage from legislation signed into law by George W. Bush, and this is basically a privatized version of Medicare. Starts off small, and over time the percentage of the Medicare market that has been taken over by Medicare Advantage [increases]. The big insurers—UnitedHealthcare, all of them—sell these. In fact, they make more money now than from anything else from these sorts of taxpayer-financed private plans.

Okay, now about more than 50 percent of seniors are enrolled in a Medicare Advantage Plan, which is, again, a taxpayer-financed private plan, and the other less than half are in the traditional Medicare program. This gives us a very nice look into what that private insurance does. So, what are some of the differences? First of all, patients with Medicare Advantage get less care. They just get less care across the board. Less doctor care, less home care, and so on and so forth. Okay, that's one thing.

Second, the insurance companies have finagled and figured out, through various machinations and mechanisms and billing codes, and by avoiding sicker people and looking for the healthier ones, to be overpaid by more than half a trillion dollars since 2007. And where is that money gone? It's gone to their bloated overhead. Medicare Advantage plans and private insurance in general take more than 10 percent of your premium for their overheads, profits, executive salaries—all the things they do that the public system doesn't need to do—and that's compared to about 2 percent of the traditional Medicare overhead. So those three things right there: denied care, higher costs, and waste due to administrative inefficiency. So that gives you a little bit of insight into why we don't need or don't want the private insurers in the system. They deny care, and they drive up costs.

And there's a simpler and better way, and we know it even within the context of the United States from our traditional Medicare program, which isn't perfect. We can talk about what it leaves undone. The VA (Veterans Affairs) also provides a model of how you can run healthcare, or Canada, where they also have a similar overhead, and they do cover everyone. So there are clear alternatives in front of our face that function better.

Robinson

Tell us more about that. You are an advocate for Medicare for All, for single payer. Why is it that you think that that one major policy change would do so much to address so many of people's complaints about the existing American healthcare system?

Gaffney

What is it that people are most mad about when it comes to healthcare? The reality is that a lot of people do like the care they receive in many situations. What they don't like is, first, the out-of-pocket costs. This is again and again a major political issue, even across the political spectrum. Drug costs, for instance, are a leading concern. People want to get the care they need and not have to make sacrifices about their rent, food, or kid’s college or whatever it may be. So, I think protection from costs and administrative hassle, from having to be on the phone with the insurance company to fight for the care you need, and for medical bills that make you fall between the cracks for whatever reason—all of these uncertainties and complexities and headaches.

Even apart from the fact that it keeps people from care they need, there's also just a psychological impact. This is not fun. I think it really makes people utterly miserable and generates huge stress. Taking a quick step back for a second though, I think if you want to understand what the fix is, you have to understand what the main problems are. And I think you can summarize them in really just three or four points.

First, we lack birth to death, seamless, continuous, universal coverage, and I think that's absolutely critical. Two, we expose people to the cost of care at the point of use, which causes rationing and avoidance of needed care and causes harm. Three, we've allowed for-profit companies to take over the system, and that has driven up waste and also creates perverse incentives, and we can talk a little more about this: when it comes to how care is actually being delivered, a Medicare for All system properly designed could actually take that out, not only in terms of the insurers, but also on the delivery side. Four, it would allow us to do all of this sustainably and economically, so that you could actually develop the tax system to pay for it and control costs over the long term so that you're not strangling the system. That's how I see it.

Robinson

Well, let me ask you then about some of the counterpoints or counterarguments that people might make. Medicare for All, although it polls well—when you ask people, should we have a Medicare for All system where everyone just gets covered in a single government plan, intuitively, people think that sounds like a fairly good idea. At the same time, among American politicians, certainly a small minority has signed on to this. And you saw in the 2020 campaign, every time Bernie Sanders would say, we should just enroll everyone in Medicare, even among Democratic politicians who were trying to look progressive, they would have some variation that wasn't really Medicare for All, and then they would give arguments. There are a lot of talking points, and they're the same talking points that are hauled out for why we shouldn't go to a full single-payer system. I want to run through them because you're great at responding to them. I think you once took on five Fox Business hosts at once.

I was going through a lecture from Sally Pipes, one of the most prominent anti-single payer advocates, who wrote a book against single payer called The False Promise of Single-Payer Health Care, and she gave a lecture at the Adam Smith Institute recently about why we shouldn't have Medicare for All. So, I want to go through a few points and get your responses to them.

The first is that in countries that do have these kinds of systems of universal coverage provided by the government, there are severe downsides for ordinary people that will make their experiences worse, and there are wait times and rationing. And I'll just quote from her,

“Single payout programs usually impose long waiting lists and delays unheard of in the US. In the NHS in England, 4.2 million patients were on waiting lists. 362,000 waited longer than four months for hospital treatment, and 95,000 waited longer than six months. In Canada, the median wait time between seeing a general practitioner, following up with a specialist was 10 weeks. Canadians wait three months to see an ophthalmologist, four months for an orthopedist, five months for a neurosurgeon, etc, etc. In Canada, the median wait time for neurosurgery after seeing a doctor is it eight months” and then a series of stimulus statistics.

Actually, that one was a quote from Scott Atlas from a Wall Street Journal editorial. So, wait times and rationing.

Gaffney

So first of all, wait times. We don't even know the wait times in many cases for many Americans because, A) some people never go to the doctor at all because they're totally uncovered, and B) we don't have that data because we don't have that universal system. Look, the fact is that many Americans are waiting a long time to see specialists. You can poll family members and friends, and you will hear stories about long wait times. It has been by no means unique to countries with single-payer systems.

Second of all, look, why is it that there's a wait? It's when there's not enough supply for the demand. When we transition to single payer, we're going to have just as much supply. We will have just as many orthopedic surgeons. There's nothing that will cause wait times to go up. We have just as much ability to deliver as much care as we have now. Right now, it is true that if you can pay out of pocket, you can go right to the head of the line. But that's not a just system. I also think there's a huge amount of selective citation of studies and statistics on this. To give you an example, for years, we heard about how, internally, the VA was causing people to die on wait lists. That was this, “this is why we need to privatize the VA.” Does that ring a bell?

Robinson

Oh, yes.

Gaffney

When researchers got data on this, they actually found that, in general, the waiting times were actually shorter in the VA than in the private sector. Just to give you an example of how misleading these claims can be, the fact is that every healthcare system is imperfect. Many systems are underfunded. The U.S. system is not underfunded. It's generously funded. As we transition to a single-payer system, we would have no new capacity constraints. We would just allocate our existing supply in a more fair and just manner, according to the patient who needs care, as opposed to just who can pay for it.

Robinson

One of the real advantages is that a lot of money that we are currently spending is wasted—the money that goes to corporate profits, that's waste. Matt Bruenig just did this great piece where he was talking about the cost savings of single payer, and he was talking about administrative costs in the United States. And his conclusion, which is kind of incredible, is that it's as if we have set up an entire economic sector that is devoted to the production of frustration and annoyance, and it's nearly as large as the education sector. It's hard to overstate, he said, how much money is essentially being set on fire.

Gaffney

That's exactly right, it's set on fire. So just to give a couple of numbers. About one-third of total U.S. healthcare spending goes to administration, and that is twice the proportion as Canada—not the dollar amount, twice the share of total healthcare spending compared to Canada. One-quarter of hospital revenues goes to administration. That's because hospitals have to hire armies of billers and coders to interact with different insurers, each with their own systems, each with their own rules and regulations, and to fight and haggle for bills. That is twice the proportion [than what we see in] countries that have single-payer systems.

The Congressional Budget Office estimates that over $400 billion can be saved annually simply through simplifying the payment system and moving to single payer, and more if you account for providers' administrative waste. So, there is huge waste. And, exactly as you said, Nathan, that money could be better spent. It could go towards care. That's kind of the point here; we could reallocate that to care. Sometimes in these healthcare debates, even in the liberal-left spectrum, we sometimes forget what the point of the healthcare system is and the point of healthcare reform. The point of healthcare reform is not merely economic. It's to improve people's lives and to improve their health, because we only have one life. We want it to be as long and as healthy as possible, and we forget that if we only focus on the dollar and cents. What a single payer transition would allow you to do is take that money and spend it on all the people who need care. There's a huge unmet need for care. We haven’t even talked about long-term care, of which there's no real system in this country. You have to basically go bankrupt before you can have access to the Medicaid system. There are real unmet needs, and we need to center that.

Robinson

Now you're talking about cost savings. One of the points that is made by people like Sally Pipes and everyone who fearmongers about Medicare for All is cost: look how expensive it would be, she says, and I'll quote from her lecture,

“Don't forget about all the taxes needed to pay for so called free care in Canada. The average family of three pays over $17,000 in taxes for its government funded, government provided coverage every year. That amount has soared by more than 90% since 1997. Even though Canadians have public health coverage, they still pay for a greater share of their care out of their own pockets than do Americans. According to the World Bank, the United Kingdom spends $10,000 per household on health, that might not sound like much, but remember, incomes are much lower in the U.K., almost 40% lower, so the taxes necessary to fund the NHS eat up a substantial portion of household income. Bringing single payer healthcare to the United States would require almost comical amounts of taxpayer money. Most estimates place the 10-year cost of Medicare for all at around $34 trillion today, the cost of total cost of healthcare in the United States is 4.6 trillion.”

And then she talks about all the taxes that would have to be paid to pay for it. How do you respond when someone says that?

Gaffney

First of all, this is not new money that we would be spending on a Medicare for All. We are talking about spending the same or less money and routing it through the government instead of to private insurers. And I can't say that enough: this is not about creating new spending streams and generating new costs. This is about taking existing funding streams and directing them to the single-payer system rather than directing them to private insurers, who take a huge portion on the way out the door. The fact of the matter is, and this is not well known—she doesn't say it—about two-thirds of total U.S. healthcare spending is already taxpayer financed. We are talking about taxpayer financing most of that remaining portion, and that could happen fairly seamlessly.

For instance, let's say you get your health coverage through your employer. They're giving you health coverage, and that premium is effectively going to the insurance company directly. How about if your employer, rather than sending it to the insurance company, sent it to the government? You would see no change in your income. Or maybe it would go up because healthcare costs would go down, but you'd see no change in your income. They would simply be routing that same number of dollars to the single-payer system. Do you want to call that a new tax, even though no one's spending a cent more? I guess so. But that's more of an accounting issue and definitional issue than what people think of when they think of new taxes.

Overall, we would spend less. This goes back to what I was saying earlier when we talked about national health expenditures: over time, we would spend less as a society on healthcare. More of those dollars would go to the government, yes, but we would spend less. That's all anyone cares about. No one particularly has some allegiance to the idea of their money going to an insurance company first.

Robinson

When I asked you about wait times and rationing, one of the implications of what you were saying is, well, yes, but those aren't necessary features of a single-payer system. They may exist in Canada and the United Kingdom, but those countries could fix those problems. The U.K. has been under conservative governance for over a decade and has fallen into what Chomsky calls the privatization playbook: ruin a public service and then point to the fact that it's been ruined as an argument for privatizing it. I suppose that same argument, that these are not necessary features of a government run system, would apply to something else that Pipes said in her lecture, which is, she pointed to a couple of horror stories. She pointed to stuff about euthanasia in Canada and also recounted at great length the story of this baby in England, Charlie Gard. This sick baby had some rare disease that wasn't covered by the state, and his parents wanted to take him elsewhere, and the courts denied permission to take the baby outside the country, and so their baby had to die because the government said their baby had to die. She said, well, that's what you get when you put decisions as to how money will be allocated in the hands of the government. I think the powerful talking point that might frighten people very effectively is when it was said that there would be death panels. Everyone treated that as ridiculous, but in fact, there are death panels. Rationing has to occur when you put these decisions in the hands of the government, and you get horror stories like that of this baby. How do you respond to that?

Gaffney

I will respond to that, and I do want to get back to what you were saying about the NHS—actually, let's talk about that first, if you don't mind, because this is true. So, first of all, it's easy to flatten distinctions. There are differences between different healthcare systems, and some of these healthcare systems are facing severe problems, including the NHS. And why is that? For a very simple reason: it's been underfunded. Now, as you said, there's this sort of Chomsky idea that you underfund something, it gets worse, and that allows you to privatize it. In the case of the NHS, it's even a little more complicated because there is privatization already, and that sometimes allows rich people to leave the system and not want to fund it anymore. It's a cycle because you undercut the political will and the economic support. The simple matter is that the NHS is underfunded. That does cause problems, that does cause strain, and the solution is to properly fund it and not privatize it. Privatization further corrodes the support base for the public system. It's very easy.

And again, in the United States, I'm not worried about underfunding. We have a very generously funded healthcare system. Many people think too generously funded. But now to go to these horror stories of Sally Pipes. Look, you could go to the United States, and I could give you horror stories that I've seen in the intensive care unit, of people who have wound up there with severe organ failures because of long-term unmet needs because of our health insurance system. You can cherry-pick these stories. Look, things do go wrong. These are countries that have millions of people. I do believe that there are cases that people sometimes have bad experiences. It would be ridiculous to say otherwise, but that's cherry-picking, and it's highly misleading. In terms of these specific scenarios with end-of-life ethics, that has nothing to do with single-payer financing. You could have a completely privatized system with all sorts of problematic ethical situations, or you could have a publicly financed system that doesn't have those things. Those are two different issues. Conflating them is ridiculous.

And even in the case of the Charlie Gard scenario, whatever one feels about that, that was not about the cost of his care. That was about different judgments from a medical ethical perspective about the proper care given the situation he was in. It was a terrible, sad situation, no matter how you look at it, but that's really just completely a lie to say that that was about trying to save money on care. These are separate issues, and the fact of the matter is that we can address each issue on its own and come to the right approach separately.

Robinson

The final common talking point that I wanted to ask you about is one that I hear a lot from Ben Shapiro whenever he talks about healthcare, and one that Sally Pipes makes as well, which is essentially that the problems with Americans’ health that are pinned on our healthcare system, in fact, has nothing to do with the healthcare system and is because Americans just live unhealthy lifestyles. Oftentimes people like Bernie Sanders and advocates for reworking the healthcare system entirely will point to the fact that we spend so much on healthcare and our outcomes are bad, or life expectancy is bad. And what some of these people would say is, well, actually, our life expectancy is low because we're fat and drive cars recklessly. Pipes says we have lower life expectancy than in many other peer countries, but that's because we have more murders, fatal car accidents, and drug overdoses in the United States, and she goes into a series of lifestyle choices that she says Americans make. And she says no health system can force people to be more virtuous, to consume fewer calories, exercise more, wear their seat belts more or commit less crime, the argument being then that the benefits of changing the structure for financing healthcare would be overstated. Looking at how bad our health statistics are really has nothing to do with the financing of our healthcare system, [she seems to be saying].

Gaffney

What annoys me about this critique is that there's a kernel of truth here, and then it is completely distorted to reach a regressive conclusion that really blames people for their own health problems. What is the kernel of truth? The kernel of truth is that our health is determined by many factors. Everyone knows this, and healthcare is only part of that, probably a minority. And so, yes, there are many things in our society that make us sick. The interesting thing is, these people actually tend to not be that invested in actually doing something about those other non-healthcare related factors. So, pollution is a major issue. Poverty. Inequality itself. Working conditions. We go on and on about all the societal factors, the so-called social determinants of health, that worsen health. Those are real and play a major role, and, literally, no one's denying it.

Again, the irony here is that they don't actually want to do anything about those things. They just want to use it as a sort of escape from the discussion at hand. That being said, I'm not that convinced that Americans have worse health habits than other people between other countries. I think smoking prevalence is higher in many European countries, which is one of the absolute worst things you can do. So it's a complicated picture.

Robinson

Diets of fast food, burgers, soda?

Gaffney

Do we have worse diets in the United States? I think that most people would answer that question, yes. But a lot of the issues that we talk about are actually facing people in most nations. Rising obesity rates are not a distinctly U.S. phenomenon, even if our rates are higher than many countries. These are complex issues, and don't get me wrong, we need to deal with them. We need to deal with them by using public resources to improve our air quality, water quality, food quality, to take people out of poverty and to engage in all kinds of social progress, things that progressives have wanted to do to make it a more just, egalitarian, and safe society. That's no question.

But then again, there is this healthcare system issue also, and we must address that first, despite the fact that people like to say it's not healthcare, it's all these other things. Actually, in the last few decades, a lot of the improvements in life expectancy are likely attributable to medical care. That's not true for the first half of the 19th century, when most of the improvements were driven by public health, or the late 19th century. But in recent decades, it is increasingly healthcare that is an important driving factor in improving improvements in life expectancy. And so, we do have to do something, and we can do better. And we know that high-quality care, coverage, and getting all the things you need does make a difference. It does save lives. It does prevent strokes and heart attacks and does help us live longer. So, they're really evading the issue with a bit of gross patient blaming that I don't like, either: not only is the healthcare system fine, but it's also your fault for dying early. And I know that's not the point you were making, but that's how it comes across to me, and I really don't like it.

Robinson

We've covered in Current Affairs the rise in pedestrian deaths, for instance, which is in part attributable to giant trucks being on the road and the bad design of American infrastructure where pedestrians take their lives in their hands in a way that they don't have to in well-designed cities such as those in Europe. I have a sense that people like Ben Shapiro and Sally Pipes aren’t interested in having a conversation about whether our trucks are too big in America—which I think they are—and cause unnecessary deaths. So yes, let's have that conversation as well. Let's have the conversation about the profiteering of the fast-food industry, which we've also covered in Current Affairs, and how they have another incentive to make people worse off and sell them crap that is bad for them.

Gaffney

We just have to talk about poverty. We know that that is one of the crucial drivers of worse health, for innumerable reasons. So why don't we, when we're talking about child nutrition, for instance, which is coming up with the current nominee for HHS? Let's address child poverty, which is important and a critical driver of poor childhood nutrition. But that's not the conversation that people want to have.

Robinson

You saying that “this wasn't caused by the healthcare system, it was caused by poverty” isn't the own that you think it is.

Gaffney

So, let's do nothing about either of them.

Robinson

Right. Are you worried about RFK as HHS (Health and Human Services) secretary?

Gaffney

Yes. Look, this is a real inflection point for us, from a public health perspective. We're already seeing, since the pandemic, sharply dropping rates of vaccine uptake among kindergarteners. It's somewhat invisible now because rates are high enough to keep many of these illnesses at bay. But if we continue on this pathway of eroding vaccine uptake, of eroding public health measures and regulations, of eroding the use of science as our predominant guiding philosophy when it comes to making recommendations for health and other things, we could be continuing down a very dark road, from a health perspective. But one thing that the MAHA (Make America Healthy Again) folks get right is that something is wrong. It is fair to say that, even before the pandemic started, there's been this alarming rise in mortality among young and middle-aged Americans, dominantly lower social class. There's something very wrong. We have to address it. It's just that we have to do it by the right means. And the right means is not getting rid of vaccines.

Robinson

Right. As with so many things, Trump identifies a grievance or discontent, speaks to people's feelings that something is wrong, and then offers them an entirely wrong and false solution.

Gaffney

And an alternative to that needs to be a progressive healthcare populism. We need to take all these broad measures to improve people's lives and health. We need to do it with science and with intelligent and just programs.

Transcript edited by Patrick Farnsworth.