How To Advocate Effectively For Reducing Meat Consumption

Brian Kateman of the Reducetarian Foundation explains how animal rights activists can avoid alienating potential allies and can successfully persuade people to join the movement.

Brian Kateman is the head of the Reduceitarian Foundation and the author of the book Meat Me Halfway: How Changing the Way We Eat Can Improve Our Lives and Save Our Planet, which has an accompanying documentary. Brian has thought a lot about how to persuade people to help improve animal welfare in ways that actually get them on board and don't alienate them. Today he joins to discuss what's wrong with the food system, why animal rights matter, and how to get people to take steps in their lives that help animals.

Nathan J. Robinson

Where I want to start is where you started the book, with what you call the SAD—standard American diet. You talk about what you grew up with eating and how you changed your mind. And I just want to read a little bit here from your book about what you ate growing up on Staten Island, in a typical middle-class family. You said, "What did we eat? Meat."

Brian Kateman

A lot of it.

Robinson

Your mom said, I made meatloaf, spaghetti and meatballs, pot roast, fried fish, sometimes lamb chops or beef stew. You said,

"meat and dairy were also prominently featured in our breakfast and our lunches. For breakfast, it was bacon eggs, grilled cheese sandwiches, steak and eggs, sausage patties, bagels and lox. For lunch, Mom microwaved pepperoni pizza, fish sticks, mac and cheese with hamburger meat or fried chicken nuggets. Whenever we were eating, no matter the time of day, we were eating meat."

You had a very typical American experience here. So tell us a little bit more about the standard American diet.

Kateman

The average American, even to this day, eats like you just described when I was a kid. It's just this 24/7, constant fast food, convenience frozen meals, with meat at the center. It's an interesting question because I currently have a one-year-old son, and I've been thinking about how differently he eats compared to how I used to eat as a kid, and it's a really interesting reminder of those differences. But the short of it is, look, my dad was busy when I was a kid, and we went to McDonald's. That's what you just did. You got KFC, you got Domino's.

I still know the phone number of Domino's. memorized in my head. You could look it up: 370-2000. I can't forget it. We called so often. And part of it was that was what my parents ate growing up. They didn't eat lots of fruits and vegetables and whole grains and legumes. The average American in the United States, looking at last year's data, ate about 225 pounds of meat a year, not including seafood, which gets us up to something like 245 pounds of meat a year. One out of ten Americans gets the recommended amount of fruits and vegetables in their diet.

And so there are many reasons for this, which we can discuss, and I explore in the book, but I do think SAD is a good term for it because it's not good for people's health. It's not good for the planet, and it's not good for animals, of course. And so we really have a historical problem here, and I think in many ways, it's only getting worse, unfortunately.

Robinson

And the reason I start here is that I feel like the first thing that we have to do is take what is obvious or accepted as natural and puzzle over it and ask: is this, in fact, normal and natural? Obviously, growing up, as you say, this is not questioned at all. It's treated as, well, this is just eating. And if you ask people, "Why do you eat this way? Why do you eat so much meat?" And maybe you have asked people this, but I feel like one of the answers that you might get a lot is, well, human beings just evolved to eat meat. Human beings are a carnivorous species.

Tell us about the explanations people might give for this, and why their own explanations for why they can't, actually help us answer the question of why, in fact, this is true.

Kateman

Yes. First, it's incredibly unnatural how much meat we eat, and also the type of meat that we eat. So if you look throughout history, not even several hundred years ago, but just a hundred years ago, my great-grandparents did not eat like this. Meat was very expensive. It was not available in the supply, and in the book, I explored these different iterations, many technological, that resulted in us having the ability to produce tons of meat and for it to be affordable and available whenever people want it.

So it's not natural. The animals and the conditions in which they're raised, and the ecosystems in which these animals are raised—if you even want to call them ecosystems because they're often just factories—are not natural. So nothing about this is natural and then, to your point, when you ask people, why do you eat so much meat? They may give intellectual reasons like, this is what we evolved to eat, or this is a natural phenomenon, but it's absolutely not true. It's not a natural way.

Now, eating some amount of meat makes sense from the perspective of evolution. There were various ancestors who would be opportunistic and would eat whatever was available to them. But even then, we were not eating 200–300 pounds of meat—nothing like that. Look, the reason people eat meat is that it's cheap, it's delicious, and it's available everywhere.

These are probably the three main drivers. And then you add in social norms, it's just what you do. And I think about the emotional attachment that I had to meat. I think about going to a baseball game with my dad, and we would get a hot dog. That's a really nice memory I have because that's what you do when you go to a baseball game, or I think about Thanksgiving and how there's going to be a turkey there, or at a Christmas table there will be a ham. And so we've just attached these social norms and sort of pleasant emotions to meat in a way that makes it very difficult for us to escape it.

Now, critically, I think when you ask people, don't you think it's a good idea to eat more fruits and vegetables and whole grains and legumes? I think people know deep down that it probably would be better if people ate more of those foods. But the truth is, it just tastes better to take a factory farm chicken and fry the hell out of it, put it with lots of salt and fat and sugar. People just like the taste of that more than they do even the best prepared vegetarian or vegan dish.

Robinson

Well, it's complicated. Because it does taste better if you've been raised that way. You and I had different upbringings. My father was a vegetarian and my mother didn't eat much meat. To me today, meat is repulsive, but you point out that, once you have all the emotional associations, once your taste has been trained and kind of learned these things, it becomes difficult to alter your ways.

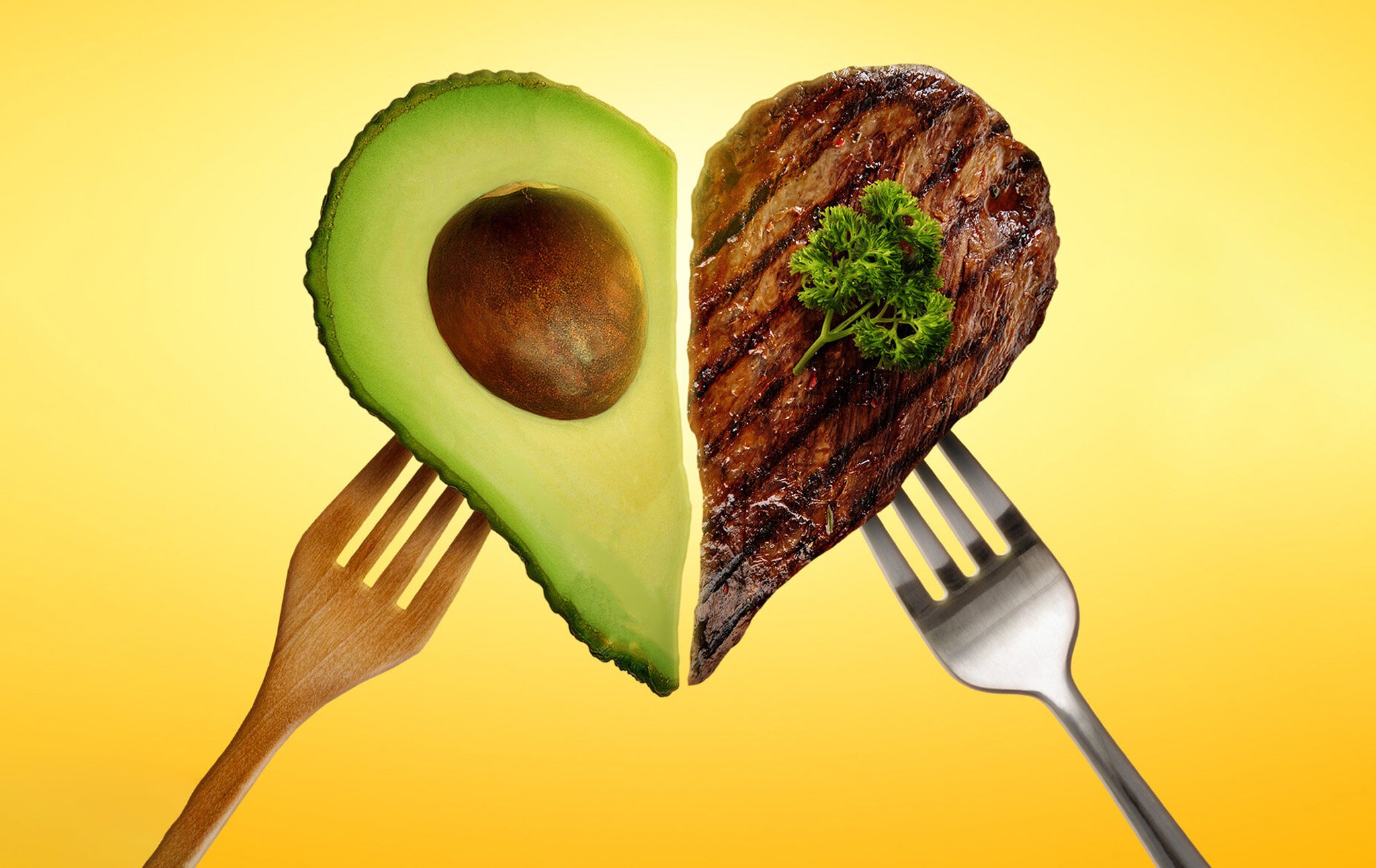

One of the most memorable scenes in your book is where you try to introduce your own parents to guacamole, having, astonishingly, never eaten an avocado in their lives. But it's true. Many people have never eaten an avocado, and you might think that they'd go, "Wow, this is incredible!" But that's not what happens. Tell us a little bit more about that moment.

Kateman

That was an amazing personal moment in my life. There's a documentary version of the book, and this is caught on film where, essentially, I go over to my parents' house and I serve them some food that you and I might regularly eat, but to them is quite strange. And one of these foods was guacamole. And my director Journey Wade-Hak had a similar upbringing to you in many respects, where he had a more varied diet, and his family was pretty progressive, but I knew my parents were going to be repulsed by this.

I think you're really on the money with respect to how their taste buds are just obliterated by eating the same foods that are really high in salt and sugar and fat. And they're very simple. They eat the same foods over and over again. And so when you introduce something novel at first, that can be jarring, and also there's a psychological fear involved. Again, my parents, I think, really represent the typical or average American. I understand there's a variance here, but if you take a sample, I think they represent the average person. They are used to eating very simple foods. When they shop, they're trying to buy the most affordable, delicious foods they can, and it's really that simple.

And so they found that to not taste good, certainly not at first. I think that with time, if they ate guacamole a few more times, their taste buds would be trained to like it more. This is why it's really important to not give up the first time after being exposed to a fruit or a vegetable. But I do have a lot of sympathy for people like my parents, despite all the work I'm trying to do to get people to cut back on animal products and eat more plant-based foods, and the frustrations I feel around factory farming.

I have a lot of compassion for people who are scared to make change. And the way I draw compassion for that is by thinking about the times that people want me to change, and I find it challenging. How many times have people told me, Brian, you seem stressed, you should meditate more. And I get it's easy to download the app, but it's takes—I don't know. It's just hard because I'm not used to meditating, or I should exercise more. I think we've all had this experience of knowing we should do something, and it's just hard for us. And my family certainly fits that that bill.

Robinson

One of the reasons I really like your approach, just to introduce the reduceitarian form of thinking here, is the understanding, perhaps informed by your upbringing and your empathy, that it's not easy for people. There are all kinds of pressures. There's the fact of how your taste buds are now, and that, as you say, it's cheaper, it's easier. Everything is structured to make it so that it's just the default option to eat a lot of meat. That asking people to go vegan in the United States of America is a big ask. It's tough. I'm still a vegetarian. I'm not a vegan. I get berated by vegans when I talk to them, who tell me everything I know about the horrible conditions that lead to my eggs and my milk and my cheese. I get it, and I try to tell them it's hard, and they don't believe me. But you do accept this. And so your whole approach has been, look, why don't we start with trying to reduce.

Kateman

Yes. When I think about the ideal vision for the food system, one of the options that is desirable is a vegan one. I'm not saying specifically, but among the options I could choose, certainly vegan is on the table, but I recognize that right now we're very distant from that place. Pragmatically speaking, I'm not going to say that you are wrong about your experience. I believe you when you say that you find it difficult to cut out eggs and dairy, and I also think there are billions of people who agree with you. Now, as someone who came from the other spectrum here of eating meat 24/7, was it as hard as I thought to significantly cut back? No, not ultimately.

Now I don't find it that difficult. But to be 100 percent all the time for anything is, of course, going to be difficult for the majority of people. And so pragmatically, let's put aside our ideals and just figure out what we can accomplish. I include you in this now because you've introduced yourself as someone who eats eggs and dairy, and I think you could cut back 10 percent more after this call. I think you could do that, and I don't think you would find it that difficult. And I think the average person listening to this, if they don't want to go vegan or vegetarian, I don't want to write them off. I want to provide them with an alternate strategy.

And I think the easiest thing to say is, just cut back. Start by cutting back 10-15 percent, and see how you feel. See if that works for you. And that has tangibly positive impacts on the planet. Keep in mind that right now, animal product consumption is going up. So when people ask me, what do I want for the future? I would jump for joy if next year meat consumption declined by one percent. And people say to me, one percent—that's nothing. Well, unfortunately, it's probably going to go up by one or two percent. So I am just a pragmatist and realist. I see the world around me. I see the systems that have been created that are in many ways destructive, immoral, and destroying our planet.

I want to work within the systems that are created and try to make a better world. And I think a reducitarian approach is one that is sensible. And I'll add it would be wonderful if some of those reducitarians ultimately go vegetarian or vegan, but it's important to recognize that it's not now or nothing, and every single plant-based meal we have is one that's worthy of celebration.

Robinson

No, I think you're right. I think I could easily go 10, 15, 20 percent. I'm always beating myself up because I'm like, oh, I can't be vegan. That seems really hard. But then your question is, how close to vegan could you get? And surely, if you just make it an all or nothing thing, then you're saying that basically you're a failure if you do 50 percent, but if you celebrate doing 50 percent, it feels a little different. There's a different way to approach it.

Kateman

Right. I sometimes think when people ask for everything, they get nothing. And I think we often do that to ourselves too. We want to be a certain kind of person, and we just find it too hard, and it's just too painful to think about our moral failures, and so we sort of just put it out of our mind. I wanted to create something positive, inclusive, celebratory—that allows you to feel really good cutting back on animal products.

Robinson

It's interesting. I teach writing, and I kind of give similar advice to people who struggle with writer's block, which is, well, write something. Just get something on the page. Just do more than nothing. It can be bad. It doesn't have to be good. It doesn't have to be perfect. Let's start doing something that gets us a little bit closer, and then we know we're closer to our ultimate goal, and then we won't be looking at a blank page.

Kateman

That's a great analogy. I think Meatless Monday is a good version of that. On Mondays, don't eat meat. Start there. Start with today.

Robinson

Now, you mentioned the immorality and destructiveness of the food system. We've talked about the standard American diet, why it's difficult to get off, but we actually need to go a little more into why it's a problem. There are many dimensions to that. There is a climate and environmental dimension. There is a moral dimension. When you talk to someone who follows the standard American diet, hasn't thought about their diet very much, and doesn't really think there's anything wrong with it, where would you start to trouble them about how they eat?

Kateman

This is a really important question, and it's important to recognize that whatever values I or other people may have who are listening doesn't necessarily mean that the people they wish to change also share those values. So it's really important to start from the place of, what is it that the person you're speaking to cares about? So I take my dad, for example. Great guy, doesn't care that much about animals, doesn't even think that climate change is happening. So what does he care about? His health. His dad died at 59 from a heart attack, and so when I think about my father and what I'm going to communicate to him, of course, I can mention environmental issues and animal issues, and we can debate the importance of those, but he does agree—knows—that eating more fruits and vegetables would be good for him. He knows that I love him. He knows that I want him to be on the planet for a long time to see my son grow up. These kinds of messages will, I think, be very effective on him and older generations, those who are not kind of clued into the stuff that maybe I care more about, like animal issues or environmental issues.

At the same time, I teach a bunch of college classes, and I find young people, on average, are more likely to care about environmental and animal issues, so I might lean in to that kind of messaging with them. So, depending on who I'm speaking to, I will tailor my messaging accordingly, and I encourage folks to do that. But it is the case that, whether folks are supportive of various moral urgencies or not, they exist. Factory farming is a problem. It tortures billions, if not trillions, of animals annually. It is destroying our planet from a biodiversity loss perspective, from a climate change perspective, water issues, on and on—and yes, it does result in all kinds of public health issues, everything from antibiotic resistance to zoonotic disease and so on. So it's a really big problem that more people should be talking about and should care about. But I'm also a pragmatist, and I want to meet people where they are, not just with respect to their diet, but also their brain and what it is that they care about.

Robinson

I do want to go a little bit more into the moral horror of the factory farming system because it is so concealed. You have that quote from Paul McCartney in here about if the factory farms had glass walls, meat eating would end tomorrow. You recount your own visit to a pork packing plant that had a mural of happy pigs on it, and how disturbing it was to be up close to the reality of it. In fact, you say in the book that even to call them, as we do, factory farms, could be a bit of a misnomer. Farm is a misnomer. These are factories. Tell us a little bit more about what you saw up close.

Kateman

Yes, I haven't sobbed like that in a really long time. It was just one of the most harrowing and also strange experiences. My director, Journey, who I mentioned, set up this experience where I would go watch pigs in trucks be essentially transported to a slaughterhouse. This is in the middle of the night. I think it was 1 or 2 AM or something. It was very late. And I felt like I was in the middle of nowhere. It was a very industrial setting just outside of LA. And I remember being with what seemed to me like hundreds of people who identified as vegan. I remember many shirts with the word vegan on it. I remember people putting up a V sign with their fingers as the trucks were going by. And I remember seeing pigs with their snouts in these sorts of holes that are in the truck, and the activists were spraying water into the truck because the pigs had come from a long distance and were thirsty, which is sad in and of itself. And then I remember hearing them squeal.

Now, I'm not going to anthropomorphize the situation. I don't know to what extent they know exactly what is going on, but it didn't sound like a pleasant cry or sound to me. And it was one of the worst smells I've ever smelled before. It was burning my eyes and my nose—the air was so noxious. I remember making eye contact with one of these pigs. And what can you say about watching an individual who you know is not that different from your dog, who you love very much in all the ways that matter, and they're trapped, thirsty, and presumably, at a minimum, confused, if not scared. They had spent their entire life in a factory farm where they’re denied basic access to what any reasonable person would consider to be humane, and then ultimately will be slaughtered.

There was a feeling of helplessness. I'm not the kind of person who was going to do this, and don't know if it's advisable—I'm not going to spear the truck driver and let the pigs run loose. I'm just watching this take place. And so there are so many little things I've learned over the years about just how awful factory farms are. Apparently, a lot of factory farmers will deprive chickens of sleep because for some reason, they wind up needing to eat less food, but still somehow gain the same amount of weight. The amount of misery and torture that is in these systems is designed that way, specifically for the purpose of creating lots of meat in a really cheap way. It’s just overwhelming and mind-boggling, and is the moral atrocity of epic proportions of our time. It makes me really sad to think about all these animals that are in those dire situations, and so how do we address that? There's a whole host of strategies, but I will say, on a personal level, one thing you can do is try to swap in more plant-based foods. Swap out of those systems.

Robinson

You write about the ways in which those basic facts about this being one of if not the most serious moral atrocity of our time are concealed by the power and the methods of the industry, and the very clever propaganda. You note many of these famous advertising slogans: beef, it's what's for dinner; pork, the other white meat; and, got milk? And how much animal suffering is successfully concealed. So talk a little bit about the industry and how this is unnatural. You track the rise of factory farming. This is not something that is inherent—we don't have to have a food system that is built this way. How does it maintain itself and prevent us from recognizing that the most serious moral problem of our time is not even a problem?

Kateman

Take that experience of where I'm outside looking at these pigs on their way to be slaughtered—I'm outside a slaughterhouse, basically. And on the wall of the slaughterhouse is this beautiful mural of pigs that are really happy, and they're wearing baseball hats. It's just this beautiful imagery. Think about the audaciousness to put that outside of the slaughterhouse. Now, you just slap that on milk cartons, and you put it in your advertisements, and so the consumers simply think that the average animal has a decent life.

Look, I'm glad to be alive. Presumably, you're glad to be alive. Maybe they go through some rough times, but aren't they happy to be alive? No, they're tortured 24/7. And so consumers don't really understand the extent of what it's like to be a farmed animal because there's all this language on it that sounds really great, like humane and sustainable and cage free, and 99 percent of it doesn't really mean anything.

I think one interesting caveat to this is that it doesn't help that these factory farm companies essentially humane-wash this entire experience. It doesn't help. I'm sure it drives much meat consumption. But here's the interesting thing. After I went to that pig vigil, I think it was a day or two later, I walked by an advertisement for some bacon. I don't know whether it was a sandwich or something, and I just remember salivating. Think about that. Just a couple of days later, after having what I would describe as one of the most transformative experiences in my life, every part of my biology just craves this bacon, and I have to override the feeling. I have to resist it. I have to keep walking past what I want, and it's only $3.99 or whatever it is, not even expensive. And so that quote by Paul McCartney is, I think, partially true. Not entirely.

Robinson

I have a similar one. My father was a vegetarian, as I say, and I was raised not eating much meat. I just couldn't ever eat meat. But when I was a teenager, I did eat some meat sometimes—not often, not at home, but sometimes. I went to see the documentary Super Size Me about McDonald's and how terrible McDonald's food is in every kind of way. When I came out of the theater, my friend and I said, we need to go get some McDonald's. Literally.

Kateman

Great example.

Robinson

We went and had McDonald's, what the whole movie was exposing! I didn't even eat McDonald's regularly! I never went to McDonald's, and it made me want to go to McDonald's because I was just seeing it—as you point out, the food is engineered to taste good. There are people with PhDs who are there in labs figuring out how to make it one percent more delicious for you.

Kateman

That’s exactly right. The salt, the sugar, the fat—we have evolved to seek out those ingredients, and they've just supercharged it. And so it's really difficult for us to resist it. And this is why, again, I have compassion. I want people to recognize that the system has been designed to endanger them and the world around us. We have to try our best to override what has been created for us. I'm not going to say it's a walk in the park, especially to start, but your example is perfect. It's just really difficult for us to resist our primal urges.

Robinson

And you also note in the book the political aspects, and the incredible book The Sexual Politics of Meat, which is just such a wonderful title, but it's true. This ties, in this country, between concepts of masculinity and meat eating. You quote James Blunt, who admitted that he, in college, only ate meat for a period because he'd wanted to seem more masculine that way. You recount your own experiences like this. And the American right wing, I have to say, really go apeshit if you start to say anything against meat. You quote Fox News saying Biden's going to take away your hamburgers and all that stuff. So there's a lot of what we might call cultural baggage that we will have to unravel.

Kateman

You're so right. It's huge. It's gotten worse. It's crazy how politicized meat has become. Plant-based alternatives, like Beyond Meat and Impossible Foods.

Robinson

Kateman

You're right. It's very sad, and it's a problem because not everyone is liberal or progressive. And so part of my job is to reach across the aisle to anyone willing to cut back on animal products. I want factory farming and its issues to be a bipartisan issue, but I'm not going to deny the reality that it has become politicized and there aren't perverse incentives at work that have made it such that the far right—take Jordan Peterson and his obsession with the carnivore diet. It's really quite silly and insane, but it has a real impact because unfortunately, there are a lot of people, particularly men, who look up to him and admire him.

And so the thing is, I'm very hopeful. I think it's possible that we're going to do this, but I'm not an optimist. I really have a pretty stark view of humanity and the forces that have been created. I just don't want us to give up because I think there's a shot, but I don't want to portray that I think that this is a given. I think it's very possible that factory farms will continue to rise for either the short term or indefinitely. I don't know what the future will be, but I really think that we need to try our best to reverse this trend as best we can.

Robinson

Well, let's then move to what needs to happen and what people are doing. You were kind enough to invite me to the reduceitarian conference that you just had in Dallas, Texas. It's sort of in the heart of meat country. When I told people I was going to a conference for people reducing meat consumption in Dallas, they thought that was kind of an interesting choice. While there, I met many people who are doing really interesting and valuable work on animal welfare and on reducing meat consumption, hundreds of different organizations doing work that a lot of people haven't heard about. I know you're not an optimist, but you at least recognize the successes that we have had. Let's talk about some of those.

Kateman

Definitely. There's a whole host of, as you said, organizations and people who are fighting factory farming to reduce the consumption of animal products, and they're using various tactics to do that. So you can think of everything from, let's say, defaults: trying to get plant-based meals to be the default in restaurants, hospitals, and schools.

There was an interesting program here in New York City in public hospitals where the default was a plant-based option for patients, and then, of course, patients could request that the meal have meat in it, but the majority of people stuck with the plant-based option, and were happy about it. Similarly, there's been initiatives to have Meatless Monday and other days of the week be vegetarian or vegan in schools in different districts in the United States. There are all kinds of efforts in the alternative protein section, which we've already mentioned briefly. So plant-based meat, like Beyond Meat and Impossible Foods, or cell cultivated meat, what you call lab grown meat: the idea of essentially growing cells, rather than slaughtered animals, and being able to turn that into meat.

And so there's a whole group of folks that are doing really promising work in those areas. There are all kinds of legal and policy initiatives to try to hold factory farms accountable for their environmental and animal cruelty damages that they cause. And so the thing I think a lot about is just how neglected this space is. The people that you met at that conference represent, I think, a significant majority, or certainly a significant number, of folks that are actually doing work in this space. So despite the fact that this is an environmental catastrophe, that it causes so many public health issues, and there are literally billions, if not trillions, of animals on the line here, there are not enough people working in this space. And so part of the thing that I think a lot about is how to get more people not just to think about their personal diet, which is important, but also to think about things that they can actually do, whether it's in their community, or whether it's to do professionally. There's a whole host of activities.

And every year I also learn about some new initiative. There's a whole host of ideas that have not been discovered yet, things that we should try. Part of the reason that I think it's important to not be too optimistic is also to recognize that we don't know what is going to end factory farming, and that should inform our humility around going all in on one strategy. Sometimes I meet people who are absolutely positive that plant-based meat is going to end factory farming, or selling cultivated meat will end factory farming, or telling people to go vegan will end factory farming. We have to recognize this is a really difficult challenge. We need all sorts of tactics from various backgrounds to try to win this fight because it's really not going to be an easy one. So I try to think about the movement as a whole.

Robinson

Well, it's interesting. The subtitle of your work is "how changing the way we eat can improve our lives". But you're not just talking about changing the choices that you make. You are talking about changing the way we eat as a system as well. Because, as we've talked about, there are so many things pushing people towards increased meat consumption. You mentioned in the book, and in this conversation, that meat is just so cheap. And it strikes me that, if we ever got to the point where the one line passed the other, and it was, in fact, the case that plant-based meat was cheaper—say it cost 50 percent of what animal-based meat costs—I think you would see a massive shift. For whatever people say about their nostalgic attachments, their masculinity, and their patriotism, I feel like if it got cheaper, you might see a lot of that evaporate very quickly.

Kateman

I think you're 100 percent right. Definitely, price is going to be a major factor. Look, let's celebrate for a moment. Starbucks recently announced that they will be getting rid of the surcharge around having plant-based milk, so you might pay 80 cents more or something, normally. That's going away, which is really exciting. And right now, plant-based milk is about 15 percent of the market. I don't know what the percentage rise will be, but there's going to be a rise. There is a group of people who would happily have plant-based milk, but they don't want to pay 80 cents or one dollar to swap from cow's milk to soy milk or oat milk, or whatever it is. So, price is huge. We need to figure out ways to lower the cost.

Robinson

Flip the surcharge, and then you get the surcharge for the cow's milk, and all of a sudden, 80 percent of people want oat milk.

Kateman

Absolutely. I would love to also see some of those external costs internalized. There should be an increase in the price of animal products because we pay for it. We pay for it in terms of climate change damage, and we pay for it in terms of health care costs. But I'd rather it is upfront, so that people reduce how many animal products they consume.

Robinson

I was just in New York City, and New Orleans is a terrible city for vegans. It has the same thing that you talk about. You talk about going to Six Flags and trying to eat some food and everything had meat in it. In New Orleans, every time I go, I ask, can I have a salad, and can the salad not have meat in it? And that's basically my option at restaurants here. But I was in New York, and I went to an incredible vegan bakery, and it was amazing because you didn't have to think about vegan options. You didn't have to make an individual choice. The choice was made for you by the fact that everything in there was just vegan. So even though I default to not buying the plant-based milk—I default to cow's milk—it was all oat milk, so there was no choice. It was great. But actually, what was nice was that the individual choice was taken out of the equation because they just made really good vegan stuff. At your conference, everything was plant-based and delicious, and you just accepted it. They just changed the system and individual choices, individual lifestyle and willpower, didn't enter into it.

Kateman

You're right. This is why we need responsible individuals and companies that have a disproportionate amount of power to help people make the right choice or to make the choices in the interest of our planet. And so it's exhausting. Look, life is hard. This is, again, the compassion. It's exhausting to have to try to be a good person. Twenty-four-seven, it's just it's also not possible. And so, yes, I wish it was just much easier. This is part of just the convenience of it. It should just be that there's some default option that you don't need to think about these.

I look at university campuses, and those are great places where students already care. It should be that 80 percent of what cafeterias offer is plant-based. But I remember going to college and I don't remember there being any salad place. I think it was literally hamburgers and chicken fingers and hot dogs, and that was all you could get. So we're seeing some progress in these areas. But as you mentioned, in plenty of places that people, I think, are not used to going. Of course in New York, San Francisco, you're going to have plenty of plant-based options, but I always come back to my roots. There are so many places like Staten Island that are not places that you and I might regularly hang out in, or at least the average person.

Robinson

And that's New York, but it's also kind of not. You talk at the beginning of the book about how people in other parts of New York say, you're from Staten Island, and we don't consider that to be the same New York City.

Kateman

Totally. It's called the forgotten borough. I literally have worked on my accent—I genuinely have practiced certain words because it often hurts my legitimacy, which is kind of sad because there are many great parts of Staten Island. But no, it's definitely not a plant-based Mecca, that's for sure.

Robinson

Let me ask you one more thing before I let you go. Obviously, people clearly ask you the question all the time: What do you think the best and most effective things that a person can do beyond reducing their animal product consumption? What do you think are the things that are worth getting involved with? What's most promising? What do you tell those people?

Kateman

Yes, I have some roots in the Effective Altruism space, so I'm certainly used to thinking about our limited resources and how we can best use our time and money, but often my response these days is a bit more general. What is it that you are good at, and what is it that you enjoy doing, and how can you use those interests and skills to help advance this space? So, for example, someone says to me, they really like law and want to become a lawyer. Go be a lawyer and help sue factory farms and hold them accountable. Or help defend plant-based meat's ability to call itself meat by defending the First Amendment. Or if someone says, look, I'm not an advocate, but I like money, so my plan is to probably work on Wall Street and try to make a lot of money.

Okay, well, have you thought about donating 10 percent of the money you make to effective charities that are fighting factory farms? I often tell people, don't be a private reducitarian. It's great that you're cutting back on animal products, but tell people that you're doing that and bring them along. Or bring a plant-based side over to your family's house for dinner.

It's these kinds of small and large things that are available to people in their everyday lives. But I really think that because there's so much uncertainty around what is going to end factory farming, I'm not tied to one particular kind of advocacy. Whatever someone is interested in doing, there is absolutely a place in this movement for them to be a part. And we have lots of resources on our website, reducitarian.org, that people can check out. And I'm more than happy to support anyone listening to this and would like to play a small or large role in helping reduce societal consumption of animal products.

Robinson

I hope they go to the site, and I hope they pick up the book, which is Meat Me Halfway, and I hope they watch the accompanying documentary, which we will link. I'll just finish here by quoting from your foreword to your book by the great Bill McKibben, who has previously been on this program.

He says, "Halfway sounds like a compromise, but in fact, this is quite a radical book and idea." And he mentions that you talk about "meeting people where they are not preaching to the choir, but providing people with tools and resources that will help them cut, simply cut back on the amount of animal products they consume, without it being an all or nothing premise, all the while supporting a delicious, affordable and convenient alternatives in the marketplace, which he calls a message of positivity and hope that if we all band together, do our part, we can create a sustainable, healthy and compassionate world for generations to come."

And you say you are not personally an optimist, but that is a profoundly positive message to end upon.

Transcript edited by Patrick Farnsworth.