Staten Island, Forgotten Borough

Staten Island gets a lot of disrespect from other New Yorkers, some of it fair. But it has its own fascinating people’s history.

What gulfs between him and the seraphim!

Slave of the wheel of labor, what to him

Are Plato and the swing of Pleiades?

poet and Staten Island resident Edwin Markham

Staten Island, the “forgotten borough,” has always stood apart from the rest of New York City, both geographically and politically. The only borough to vote for Donald Trump (in both 2016 and 2020), Staten Island has long been a red island in the blue sea, voting Republican in 11 of the last 14 presidential elections. “‘Staten Island’ has become New Yorker shorthand for an out-of-the-way, irrelevant place,” City Journal says. For many years it was infamously home to the world’s largest garbage dump, the Fresh Kills Landfill. (It has since been turned into a park.)

Staten Island’s political separateness has a long history. Phillip Papas, in That Ever Loyal Island, reports that when the American Revolution broke out, “99 percent of Staten Islanders remained loyal to the Crown by defying the colonial resistance movement and refusing to support American independence.” Staten Islanders clashed with others in the New York state government, and “the Staten Island delegates tried to thwart every measure that strengthened the colonial protest movement.”

Even Pete Davidson, who is from Staten Island and starred in The King of Staten Island, shits on Staten Island. “A bunch of Trump-supporting fucking jerk offs. Fuck them,” he told an interviewer. Additional comments Davidson has made on his home borough include “Hurricane Sandy should have finished the job,” “[it’s] the herpes of the five boroughs,” “a terrible borough, filled with horrible people.” “I know Staten Island isn’t all heroin and racist cops, you know,” he said. “It also has meth and racist firefighters.” (Despite all that, he still hangs out here a lot.) Staten Island may have given the world the Wu-Tang Clan, but not only did Staten Island vote for Trump, it gave him 82 percent of the vote in the 2016 Republican primary, the highest percentage of anywhere in the state.

And yet: Staten Island is complicated. In 2016, support for Bernie Sanders over Hillary Clinton was far higher in Staten Island than Manhattan. Staten Island is the most union-dense borough in New York City and probably one of the most pro-union counties in America. (I’ve never been to another place where you might openly talk to strangers in a deli about unions as casually as you would a baseball game.) And in 2022, Staten Island was where Amazon warehouse workers finally defeated the Bezos machine in a union election, creating “one of the biggest victories for organized labor in a generation.” To see Staten Island as a nest of reactionary suburbanites is a mistake. When you look beneath the surface, Staten Island has its own unique history of popular struggle.

Historically, when things got too hot for revolutionaries in their homelands, some of them found themselves hiding out on Staten Island. Lajos Kossuth, the Hungarian revolutionary and independence fighter sometimes called the “Hungarian George Washington,” stayed on the Island. Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa, the 19th-century Irish republican rebel who has been called “the first terrorist” for organizing the “dynamite campaign” against Britain, went to live on Staten Island after being exiled by the British. Rossa continued organizing against Britain from his New York home, and in his memoirs issued a stirring defense of being “mad”:

I have myself been called a madman, because I was acting in a way that was not pleasing to England. The longer I live, the more I come to believe that Irishmen will have to go a little mad my way before they go the right way to get any freedom for Ireland. And why shouldn’t an Irishman be mad; when he grows up face to face with the plunderers of his land and race, and sees them looking down upon him as if he were a mere thing of loathing and contempt! They strip him of all that belongs to him and made him a pauper and not only that, but they teach him to look upon the robbers as gentlemen, as beings entirely superior to him. They are called “the nobility,” “the quality”; his people are called the “riffraff—the dregs of society.”

Another fascinating radical was John De Morgan, an Irish populist who became infamous in England during the 1870s, where he “was involved with virtually every imaginable radical cause, at various times a temperance advocate, a spiritualist, a First Internationalist, a Republican, a Tichbornite, a Commoner, an anti-vaccinator, an advanced Liberal, a parliamentary candidate, a Home Ruler.” De Morgan “zigzagged nomadically through the mayhem of nineteenth century politics fighting various foes in the press, the clubs, the halls, the pulpit and on the street.” In England, he started various short-lived publications, some of which were named after himself (De Morgan’s Monthly, De Morgan’s Weekly), some of which were grandiose (The People’s Advocate and Natural Vindicator of Right Versus Wrong) and some of which, like this publication, aimed to conceal their radicalism beneath a banal title (House and Home). De Morgan traveled thousands of miles and gave public speeches to hundreds of thousands of listeners, and eventually received support from Marx and Engels to work for a newly-established International Workingmen’s Association. After spells in prison, De Morgan finally emigrated and landed on Staten Island, where he entangled himself in new causes. He campaigned to keep Staten Island from becoming part of New York City, saying in 1884 that he “shudder[ed] to think of the time when our lovely hills and beautiful valleys shall be made as unsightly as the dirty streets of New York,” and warned that “the neat little cottages with their tasteful gardens shall be swept away, and row after row of brick or stone houses, factories and gin mills [will] occupy their place.” Others on the island disagreed with him and ten years later voted in overwhelming numbers to join New York City.

But De Morgan did leave a legacy on Staten Island. He campaigned for public parks, and in 1900 lobbied the New York State Assembly Committee on Cities to fund the establishment of Silver Lake Park. Legislators were evidently swayed by his argument that “the people of the community have a right to recreation and pleasure grounds, where … their children [can be] kept from the contaminating influence of the saloon.” Money was appropriated to create the Silver Lake Park Commission, and today, Silver Lake Park is a “209-acre oasis” that serves as “Staten Island’s answer to Central Park.”

One of the more interesting historical political leaders that found their way to Staten Island was General Antonio López de Santa Anna, the five-time (or six-time, depending on how you count) president of Mexico who lay siege to the Alamo. While on Staten Island, Santa Anna introduced chicle to an inventor, who developed it into an early form of chewing gum (and whose American Chicle Company would be, for a time, the largest chewing gum plant in the world).

For about two years, Staten Island was also home to Giuseppe Garibaldi, considered the liberator and unifier of Italy, admired by figures ranging from Abraham Lincoln to Friedrich Engels. (Lincoln even offered Garibaldi, whose command of military strategy was legendary, the command of a Northern army during the Civil War.) During his time on the island, Garibaldi lived with Antonio Meucci, an inventor who created what is argued to be the first telephone. Meucci invented the device to communicate with his wife from his workshop after she became bedridden. But Meucci’s life in Staten Island was marked by struggle. He “struggled to find financial backing, failed to master English and was severely burned in an accident aboard a steamship.” He could not afford to apply for a patent for his telettrofono, and Alexander Graham Bell was ultimately granted one a few years later. When Meucci died, he was still engaged in a lawsuit against Bell. (In 2002, the U.S. House of Representatives passed a resolution honoring Meucci’s “work in the invention of the telephone.”)

The house where Meucci and Garibaldi lived sits on Tompkins Avenue in the Rosebank section of Staten Island. Today it serves as a museum for both men and the work they did while they lived on Staten Island. But on July 4, 1932, the Garibaldi monument on Tompkins Ave. was the site of an antifascist battle. The “Battle of Staten Island,” as the New York Times would report, was led by the infamous Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) organizer and one of the leaders of the great Paterson Silk Strike of 1913, Carlo Tresca. Tresca led a group of antifascists against the Mussolini-aligned, Italian civic groups that had developed a following among the Italian American population of the Island. Each claimed the legacy of Garibaldi for themselves. The fascists attempted to make the revisionist case that Garibaldi’s politics were the precursor to fascism, while the antifascists considered this a perversion. The Times provided a colorful report of the Battle:

About 4 p.m. [the antifascists] decided to hold an indignation meeting in the street, at which they denounced the police and the Sons of Italy and voiced their claims that since the shrine had been dedicated with funds contributed by Italian-Americans generally, they had as much right to hold services at the Garibaldi statue as the Sons of Italy. … By 5:30 the anti-Fascisti numbers were augmented with 150 new arrivals. Then they waited the arrival of the rival faction. In half an hour, about 3,500 members of the Sons of Italy from all parts of the city, led by a band and their guest speakers, marched to the Shrine. As the main gates swung open to admit them, the anti-Fascisti surged forward, booing and yelling and bearing their Garibaldi wreath aloft. The Sons of Italy answered with boos and yells equally lusty. …[The] police guard charged down on the anti-Fascisti, swinging their clubs freely. In the melee the big wreath was torn to shreds, and after a brisk passage at arms the anti-Fascisti were again hurled back a block. As they retired they dropped numerous brown paper parcels containing weapons in the form of iron bars, bolts, pieces of cable and pieces of iron bedsteads. By this time, the Sons of Italy had entered the grounds and the gates were closed. They immediately began their program of exercises, but the speeches of the Italian Ambassador and Mr. Pope in praise of Garibaldi were drowned out by the roars of the angry gathering outside the fence. Despite the uproar, the ceremonies continued. Before they ended, some of the members of the Sons of Italy left the grounds and boarded a three-car train of the Staten Island Rapid Transit Company for the ferry terminal. Members of the anti-Fascist group boarded the same train. The shooting occurred just as the police were breathing sighs of relief, believing that the disturbances had ended for the day.

These are not stories that are widely known by my fellow Italian Americans on Staten Island. I’ve asked many of them. But whenever the “Columbus question” comes up—should Italian Americans continue to celebrate a genocidal monster who sailed under the Spanish flag?—I wonder why we never think of simply replacing Columbus with Garibaldi. The “liberator of Italy” lived on Staten Island, arguably the most Italian place in the United States. (Nearly 36 percent of the population is of Italian descent, making Staten Island the most Italian county in the U.S.)

So many aspects of Staten Island’s rich history have simply been under-studied. There are no comprehensive works on Staten Island’s labor history, as I found out when I started doing research on it for my master’s degree in labor studies. In fact, the major works on Staten Island’s history paint a picture of it as a tranquil place lacking social struggle, where business owners make decisions meant to improve the happiness of their workers. That utopian story can’t be true, though, since there is evidence for the existence of unions on the Island dating back to the mid-19th century.

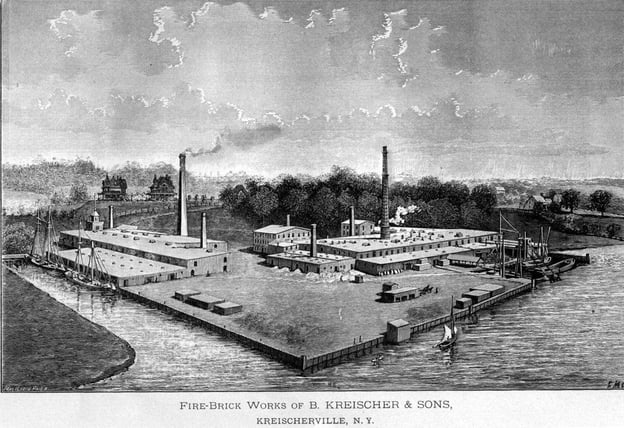

We know that there was a company town named Kreischerville, named for Balthasar Kreischer, the man who owned it. Kreischerville made bricks and tiles, and Kreischer himself built “a massive 26-room Italianate villa” on a hill overlooking the town, from which he could observe the people of his town going about their business. We also know that there was an area of the island called “Factoryville,” which sounds like it may have its own sordid forgotten history.

Kreischer Brothers Mansions on the Hill Overlooking the Town Named After Them

When Meucci and Garibaldi lived together, they helped start the borough’s first brewery, and Staten Island breweries soon flourished. Brewery barons were important local figures, though the major breweries died out by the middle of the 20th century. (The Flagship Brewing Company, founded in 2014, is trying to put Staten Island beer back on the map.) There is some evidence of labor strife; George Bechtel, owner of Bechtel’s Brewery, is on record as having given in to the demands of workers threatening a strike in the late 19th century.

Some of the Staten Island brewery workers were represented by the Knights of Labor, but there is also evidence of IWW militancy burgeoning in 1906. In fact, some of Staten Island’s IWW activity has been overlooked because of a mistake in an early source. Paul Brissenden’s 1919 book, The IWW: A Study of American Syndicalism, attributes silk workers locals 176 and 190 to New Haven, Connecticut. And the University of Washington’s 1906 IWW yearbook lists a “West New Brighton, Connecticut, silk strike.” There is no West New Brighton in Connecticut, but there was one in Staten Island. The IWW’s second convention explicitly talks about the Staten Island silk strike multiple times and attributes it to local 176 of New York.

The labor history of Staten Island may be richer than is assumed by those who see the island through the lens of its stereotypes.

Women played a key role in the labor militancy of the early 20th century, and some of the most important labor leaders and organizers hailed from or moved to Staten Island. Ella Reeve Bloor, more commonly referred to as “Mother Bloor,” was born in Sailors’ Snug Harbor (West Brighton) and went on to investigate the conditions of the meatpacking plants in Chicago for Upton Sinclair’s famous muckraking book, The Jungle. Mother Bloor’s writing would become inspiration for a Woody Guthrie song, and Bloor would go on to be a founding member of the Social Democracy of America political party alongside Eugene Debs. She also played a role in the founding of the Communist Party of the United States and was one of its leaders for decades.

Last year, one of the Staten Island ferry boats was named for another famous local radical, Catholic Worker movement founder Dorothy Day. Day and Peter Maurin began the movement when Day was living on Staten Island. Day, an anarchist, advocated a program of direct action in serving the poor and is now under consideration for sainthood in the Catholic Church. If approved, she would be the first saint from New York since 19th century educator Elizabeth Ann Seton, who founded the Sisters of Charity. Seton was also from Staten Island, having grown up in Tompkinsville. Seton was the first person born in the U.S. to be canonized by the Church, meaning that if Day is approved, Staten Island will have produced both the first American saint and the first American anarchist saint.

At the Staten Island Museum, which has been open since 1881, more research is being done on the important local women who have impacted Staten Island, the country, and the world. Museum archivist Gabriella Leone (who has assisted me in my own research) has been trying to uncover Staten Island’s history from below, producing findings on trailblazing women from the island who further complicate Staten Island’s image as a bastion of conservatism. (Gabriella has also curated Women of the Nation Arise!,a museum exhibit about the fight for suffrage on Staten Island, viewable on the museum’s website.) Debbie-Ann Paige, a historian and genealogist who serves as co-president of the local chapter of the Afro-American Historical and Genealogical Society, has created an app called the Staten Island African American Heritage Tour and has helped in the preservation and protection of Sandy Ground, one of the oldest continuously inhabited Black settlements in the country. Sandy Ground was an important antebellum free Black community that served as a stop on the Underground Railroad.

The environmental movement has its own long history on Staten Island, having existed there for over 100 years. Staten Islanders waged a major fight over the presence of the infamous Fresh Kills landfill, with the garbage having been dumped on the island in part because its residents were comparatively politically weak at the time. But environmental activism on the island has been much better documented than other parts of its popular history, perhaps because the movement’s participants tend to come from more elite social backgrounds, their history being better preserved than that of average workers.

Allison Nellis is a native Islander who is also digging into the forgotten history of the Island. Discussing the need to tell history from the perspective of those who don’t usually get a voice, she told told me:

The one thing I wish people knew about Staten Island History is how much work there still has to be done. We’ve gone for so long not questioning the written history of our borough and its glaring problems. We have to do better with making sure communities of color, women, immigrant communities, and the LGBTQIA+ community are acknowledged in our story.

Stereotypes about Staten Island as a place of monolithic conservatism, then, persist in part because the voices of marginalized Staten Islanders simply aren’t heard. Fortunately, as we resurrect this lost history, the existing narratives come undone, and the borough’s complexities can finally be broadly understood.

January 11, 2023, marks an important day in Staten Island labor history: Amazon lost its bid to overturn the historic victory of workers who voted to form the first union in an American Amazon warehouse.

There was a lot of skepticism about ALU’s chances of winning a union election. I was working as a labor organizer myself at the time, and I too didn’t really think there was a chance they’d win. The day of the count was unforgettable and thrilling. ALU’s win upended the established order of labor relations and revived the idea that large corporations could be fought and defeated. Relentless union busting efforts by Amazon failed to sway the Staten Island workers.

Staten Island is actually the perfect setting for an unorthodox and independent union struggle. ALU isn’t even the first independent union at one of America’s largest corporations to be built on Staten Island. Procter and Gamble had a plant on Staten Island called Port Ivory, and their union was the Procter and Gamble Independent Union of Port Ivory. Staten Island may stand apart from the rest of New York City, but it has a spirit of independence. It deserves to be known just as much for the Amazon Labor Union as its status as “the only Republican borough.”

Like many people who grew up in working-class neighborhoods, I look at what happened to the kids I grew up with, and I find that many are dead from drug overdoses, about a quarter are locked up or fell off the face of the Earth, and the rest are surviving as best anyone can. Staten Island has the second-highest rate of overdose deaths among the five boroughs. A lot of the kids from my neighborhood got swept up in the personality cult of Trump. My experience is that many of those people were voiceless and looking for a voice, at a time when institutions have failed us.

But those in my generation were also radicalized. Back in the early 2000s, after Columbine and 9/11, we turned to Michael Moore’s documentaries, George Carlin’s standup, and revolutionary rappers like Immortal Technique for answers. I know that many of the people who ended up voting for Trump once lived and breathed anti-authoritarian, anti-war, and anti-oppression principles. We were street kids who didn’t read political and economic theorists. We couldn’t conform to rules and commands from adults, but we were all smart in our own ways. We didn’t follow party lines.

Staten Island isn’t just full of racist neofascists (though it has that element, as the antifascists of 1932 discovered). It’s just that the full history of the place, like the borough itself, has often been forgotten. We need to recover from a narrative that leaves the working class silent and cares only about the memory of the masters. We have to stop forgetting.