Why You Will Never Retire

Economist Teresa Ghilarducci on why some 90-year-old Americans are pushing shopping carts in the heat trying to make ends meet.

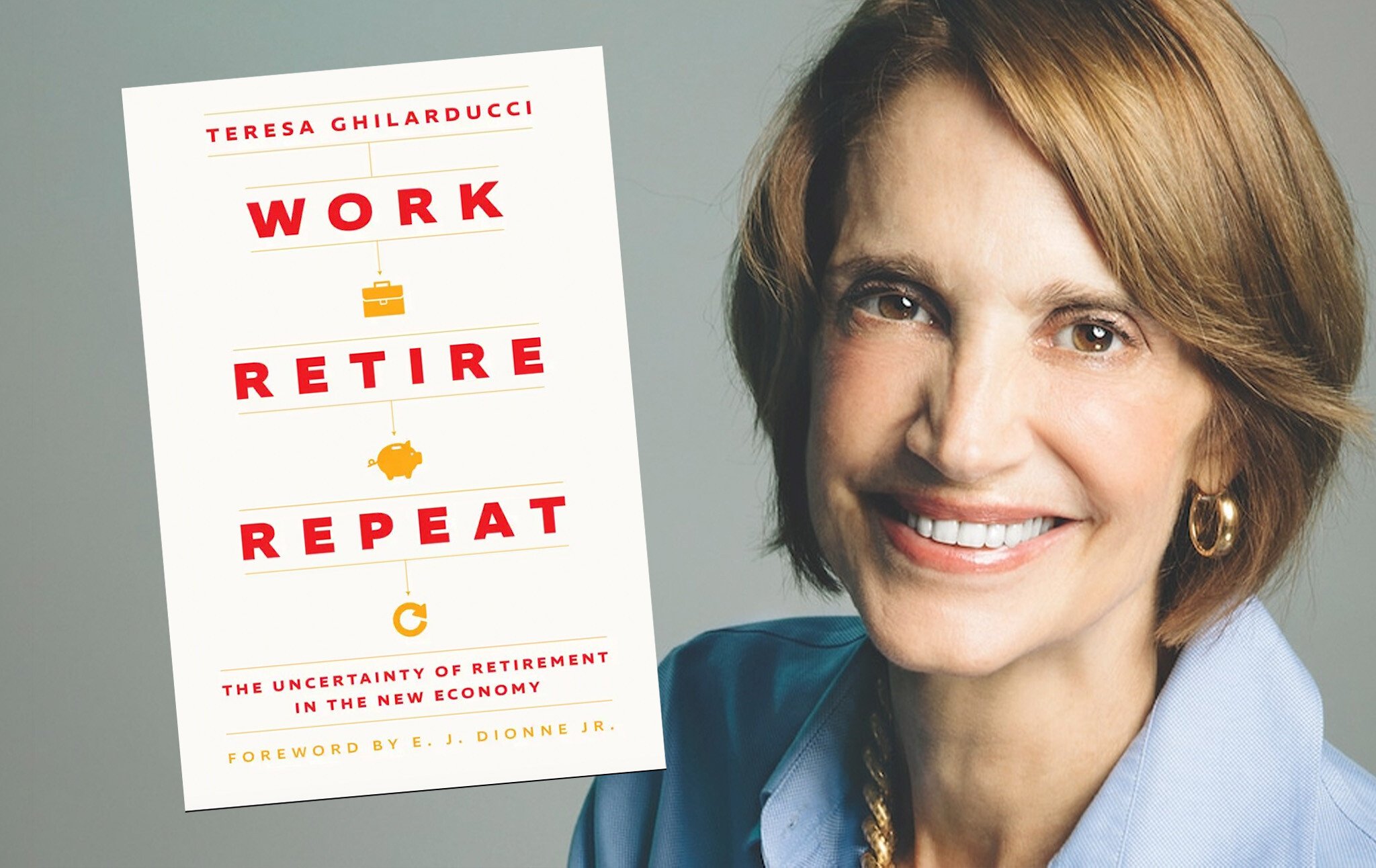

Teresa Ghilarducci is an economist at the New School for Social Research and the author of Work, Retire, Repeat, which shows how the possibilities for having a comfortable and dignified retirement are slipping away. Prof. Ghilarducci explains how it can be that in the richest country in he world, a person that age can still be having to work. She shows how the pension system disappeared, why Social Security isn't enough, and explains how even the concept of retirement is beginning to disappear, with many arguing that work is good for you, people should do it for longer. Prof. Ghilarducci also explains how things could be different, advocating a "Gray New Deal" to help older Americans experience the comfort and stability they deserve after decades in the labor force.

Robinson

I want to begin with something that I saw in the news just a couple of days ago—too late to appear in your book, but your book has a similar anecdote that opens it. I saw a story from my own state of Louisiana: "Donors raised $233,000 to give us cart pusher, age 90, a chance at retirement. Dylan McCormick, an Air Force veteran, had been supporting himself by pushing carts in Louisiana's triple digit temperatures. In 90 degree temperatures, it felt like 103.”

A former TV news anchor saw this man, who was 90 years old, pushing carts. She asked him, “It's Memorial Day. You're out here working.” She said, "May I ask why you're working here at age 90, pushing cards in Louisiana heat?” And he replied with two words, which were: “to eat.” And so she, being kind of horrified by this, managed to raise $233,000, which is great. That's all good. We like that.

You begin your book with a similar anecdote from 2022 about an 82-year-old Navy veteran who was working at Walmart, and there was another fundraising campaign that raised about $100,000 so that he could retire. So, we see these news stories bubbling up from year to year.

I want to start by asking you: why are we in a situation where a 90-year-old Air Force veteran is pushing shopping carts in the Louisiana heat?

Ghilarducci

Thank you for that story. It does break my heart and brings up a lot of emotions of shame about our system that has broken down, and that's the reason why a 90-year-old is pushing carts: to eat. He didn't say he loved the job or liked the people and loved the structure that job gave him during the day. He didn't say that at all. He didn't say that's where he meets friends and gets meaning from work. The system broke down.

Forty years ago, we started what I call the do-it-yourself retirement system, where people were asked to save for their own financial futures, and it looked really great on a spreadsheet. All you had to do was find an employer that would sponsor one of these 401K plans, or you could save it on your own in a bank or in an individual retirement account, but the focus was on the individual's responsibility to put money aside, and if you did it in your 20s or 30s, the power of compound interest and the financial markets would mean that you would have enough to supplement your modest Social Security.

So, it looked great on paper. All you had to do was have extra money around to save for retirement. You needed not to touch it for those years. That meant you need not have any emergencies or any instability in your life or in your family's or community's lives that might need that money. You would also need to have an employer that would contribute to that plan. You would need to know how to invest it well, so you had to be a semiprofessional financial planner—and this is the real hard part, even though those other things are hard too—and if you ended up at age 62-65 with a lump of money, you had to know how to make it last to pay for inflation and for an uncertain lifetime, an uncertain death, which is actually a very hard problem for even the professionals to solve.

So, the system broke down because it was based on an individual responsibility to kind of do it yourself. It's as if, 40 years ago, we decided that everybody needed to know how to do their own electricity. We would have had a lot of wiring mistakes and a lot of tragedies along the way. And that's actually what's happened with this system.

Robinson

I deliberately gave a few of the details from this story because I think each one is kind of interesting. It's interesting that, of course, this man was found by a local news anchor. This is wonderful, and when these stories pop up, sometimes they're presented as quite inspiring stories that the community came together. I think that what we can see here is that because people chipped in money for this guy, they don't think this is fair and that this man ought to have to push carts. They are willing to give their own money because they see this as a situation that shouldn't exist. They don't say, why should I give money? This is just a man working a job. They see this as something that he should be allowed to have. This man is 90 years old.

Ghilarducci

Yes, you bring up a really good point because also embedded in the system is a kind of lack of dignity. I remember having to avert my eyes when someone as old as my grandmother was wiping down my table in McDonald's. I looked up and saw this old woman doing this menial work for me, and I really had to turn away. So, what this news anchor did, I guess, was feel that. It also inspired the GoFundMe, or in the way she told the story, she was able to raise money. I also have an incident in my book where 10-year-olds did that for their 80-year-old janitor in Texas. So even people who haven't entered the labor market who are still children see that this is wrong, and it's also very unique to Americans. So not only is it wrong, it's not a universal condition among rich countries that look like us.

Robinson

I keep mentioning the news anchor because I feel like it's such a random act of chance. He happens to run into this woman, and she happens to be able to mobilize and communicate with the public in a way that can raise some money. But you say at the beginning of your book, people working until someone does a random act of kindness and collects money on TikTok—are we heading for a TikTok pension system? If this was our actual system, if this was the way of making sure that people like this man could retire, we need three million more GoFundMe accounts for working people older than age 75. So, this is always going to be such a fickle way of helping people. It's like relying on the lottery to take care of people.

Ghilarducci

Right. Charity is not justice, and an inspiring story is not a fix. I should have said in the book—I just realized the mistake—it's three million random acts of kindness every year.

Robinson

Oh, okay. Annually.

Ghilarducci

Right. For every year. It's only getting worse because people are coming into retirement at a scale we've never seen before. The population is just bigger. We have 11,000 people turning 65 today. Now that will slow down a little bit, but there is no better system facing Gen Xers or Millennials that these Boomers are facing. This guy, I guess, isn't even a Boomer. He's past that. The fact that he's a veteran also really interesting.

Robinson

Yes, I wanted to ask you about that because the guy in your story is a veteran. I think one would have thought that veterans were at least taken care of.

Ghilarducci

I know. They were federal workers, and when you get out, you do have some benefits. It might be happenstance, but he's one of the lucky ones. First of all, we saw him. He actually was a 90-year-old and was robust enough to be able to push carts, and that may have been because of his veteran status. So, remember, the two examples are people we see who are out there, and my research has shown the people who don't have enough money but still can work are the lucky ones. Twenty-eight out of 100 people between the ages of 62 and 70 need to work and are able to work, but 52 of those 100 people are actually retired and don't have enough money to live on. They're the ones behind closed doors. As you get into the older ages, working is quite extreme, but being out of money is not extreme. Being out of money as you get older and older is more and more common.

The risk of poverty, especially for an older woman, is the highest she'll ever face because she's older. A single person, as they age, is most likely to fall into poverty. So, it's a system that builds in decay as people get older, and it's a system that is structured so that many people are left out. You asked me about him being a veteran, we see him, and it's probably because he's actually among the lucky ones. Veterans have pensions, but it's not enough, and usually people aren't in the military for their whole careers. So, he's a veteran, which also represents people who are in and out of employment and who have to switch industries. If you stay in an industry, stay in a job, have a rich and generous employer, you do the best in the system. Everybody else is at risk of working into their 70s and 80s.

Robinson

One of the things that you point out in the book is that if we debate about whether working in your 70s and 80s is a good thing, it really kind of depends on what you're doing. The experience of old age is very different for different people. And one of the reasons that I highlighted the fact that this guy is pushing carts in a 100 degree weather is that I think nobody would have a theory that it is good for a 90-year-old to be in the boiling Louisiana heat all day against his will. I think no one can argue that he's living an active lifestyle.

Ghilarducci

You'd be surprised at the people who would praise that 90-year-old doing that. Maybe it was a hot day; it's not always that hot. Or the 100-year-old yoga teacher I have in my book, or the Harvard healthy newsletter that I quote, which is just a fraction of the kind of literature you get in America. Believe me, this literature and these stories, what Deirdre McCloskey calls "the bourgeois virtue of work, work, work," does not show up in other cultures. The people who say it's good for people are why I wrote the book. I was really methodically interrogating this throw off comment, which is, we don't have a retirement crisis; everybody is working longer, and therefore they can work longer. Each part of that sentence and that policy recommendation and push, that we don't have a retirement crisis because everybody's working longer and can work longer, is really based on things that say work is good for you in old age because it gives you structure to your time, gives you friends and prevents social isolation, and is good for your brain. All of those things, according to my research, just aren't true for most people. Most people have jobs where you don't control the pace and content of the work. You certainly don't control the environment in which you work, or the temperature with which you work in, or how often you can go to the bathroom or connect. Most jobs that older people have aren't jobs that lend themselves to sociability. You're plugged into an earphone and Amazon workhouse, or you're an old person taking care of even older people, or you're a janitor working alone. These are three occupations—warehousing, home and personal health care, and janitorial services—where you have disproportionate numbers of older workers who are some of the most low paid workers in society, and these are some of the most profitable industries in society. So, there's a synergy between tens of millions of older workers needing to work and these industries that are very profitable that depend upon their desperation.

Robinson

Yes, I might have thought, and I suppose I didn't really realize this until I read your book, that it's not universally agreed upon that retirement is a good thing. I sort of assume everyone wants to retire, and that everyone thinks that you should have a nice, long, comfortable retirement at the end of your life. But there is, in fact, what you call the working longer consensus, which is that life expectancy has increased, and now we want active aging. In fact, I've heard Republicans say quite outright, we want people to work longer; as long as you can work, you should work. So, the idea we actually do, in fact, have to make a case that there should be a period of your life where, even if it is technically possible for you to continue some kind of labor, you should not be economically coerced into doing that. It is not obvious to everyone that that is the case. That is a moral argument that you have to convince people of.

Ghilarducci

It's actually the idea that every worker, after a lifetime of work, deserves their retirement, or what I call a period of time in which you can choose what you want to do. If you want to work, you can work. If you don't want to work, there should be this deserving period of time when it's legitimate to be able to choose what you do with your time. Most other cultures, most other countries like us, don't have to keep making that case.

Robinson

Yes, you don't have to make that case in France.

Ghilarducci

Which is kind of a weird country. You see this in Scandinavia. I don't even bring them up. But the there are a lot of hard bitten capitalists and pro-work people in the Netherlands, and they look a lot like us, pump oil, have finances, and are hard workers. But you don't have to make a case that there's a period of time in which you are rewarded, and in fact, it is a renewed kind of demand that comes from workers. Workers here in this country had to actually demand for pensions. They went on strike for pensions, and it became kind of an expected way of living. And then something happened in the 1980s in America where that really reversed. I talked a little bit about that reversal of legitimacy that came about with the decline in unions. It came about with a cutback in Social Security. It came about where these frustrated politicians said, it doesn't look like we're going to get Congress to put more money into Social Security, and it doesn't look like the workers have enough clout to get pensions, so what are we going to do? Oh, we could have this magical solution, and I think little kids have this magical solution too, which is, if everybody just works longer, we don't have to fund pensions. So, it became a belief of convenience. It became kind of what I call a convenient lie that people could work longer because the convenience of that lie means that we don't have to plan for it. And in other countries, every once a while, a politician will grab onto that convenient lie, but the people there, like in France you alluded to, took to the streets and said, no, we still want to be able to retire. They lost—their retirement doesn't start at 62, it now starts at 64, but wow, Americans would be really happy if they had a legitimate claim to retirement at 64. Now, people don't have really a legitimate claim to retirement unless they really fight for it. It's just not built into our system. What's built into our system is that it's your responsibility to save for your own retirement if you don't have above work.

Robinson

One of the things I do like about your book is that it's just the very fact that you operate on the premise that retirement is a good thing, and that retirement used to be a social norm. That, in fact, is just not universal believed. You have this remarkable anecdote that at one point you were on a panel of retirement finance experts, and you were asked to call retirement something else, to not even talk about retirement.

Ghilarducci

And I'm a polite person, but I really wanted to groan and put my head on the table, which would be something like, you've got to be kidding, or, how far have we fallen? I also want to say something I usually don't say, which is that I've been writing this book for 10 years, and I was unable to find a publisher for the first five years. The editors would turn to me and say, I have a father-in-law who just uses his Social Security to go on trips and to go golfing. He meant that as a bad thing, and I thought it was a good thing. So, we didn't meet eye to eye. But 10 years ago, even three years ago, an economist saying that we should build into our system that people should be able to retire was really rebuffed by older senators, congressmen and academics, who are oddballs. As I say in my book, being a politician or a tenured professor means that you have really an oddball career and expectations. You get to decide what to research, what to legislate. People work for you. You get to read. It's not heavy lifting. But the academics and the politicians are the ones that are making the policy. So, I think this book is a real triumph, not for me or my publisher, but as a crack in the system and this kind of belief that we can stay young forever.

Robinson

Yes. Part two of your book makes the case that it is just not correct to assume that for most workers—as I say, this is all bifurcated. You could have jobs where you never want to stop working because your job is to sip coffee and read books and occasionally write an article, which sounds lovely. I'm a writer. I don't necessarily want to retire from writing because what I do is sedentary and lovely. But you point out that working longer is not a choice for people. It can harm your health, and kind of paradoxically, you say that working longer does little to improve retirement security.

Ghilarducci

Yes, that really surprised me. There are two chapters about the myths of working longer, and one of them was, does working longer actually make you more cognitively engaged? Does it make you more engaged in community? Does it actually help with your social isolation? And it was really hard because every time I would finish for the day, another research paper got published the next morning. That was really frustrating. I just couldn't put that research to bed.

But I could see the evolution of that research. The researchers wanted to find that working longer made you healthier, and you could just see them reluctantly finding out there's no effect, and then other researchers asking, what are the damaging health and mental effects of being in a subordinate position? That research really concluded that only for a few occupations does working longer add to health and longevity. Then the next chapter is about whether it actually adds in more money. Lots of spreadsheet simulation shows that if you work until 70 and do whatever you can to stay into the labor market, you will be able to delay collecting your Social Security, because everybody now knows that if you delay collecting your Social Security, you get more. So, that makes sense, just do that, and if you work, you can save more for your retirement. And if you get the extra benefits of having friends and structure, then there's no problem. You will have more money in your savings account when you're 70, and you actually have a shorter period of time to retire. But first, I found out that most people who are working don't have a way to save for retirement at work. There's such a low pay that they have to drain their 401K accounts, and they have to collect Social Security earlier to supplement their low pay. So, by the time they're 70 they don't have any of those goodies that the spreadsheet said they would have. But it's true it’s more affordable only because they have less retirement. It's like me saying I have a solution for you not being able to afford lunch: skip it. Problem solved. So what’s behind the advice to work longer to solve your retirement has embedded in it the assumption that working longer to solve your retirement is to shrink your retirement.

Robinson

Right. Because when you're working, you have an income, so a why not just work. So, there is no retirement. Let's assume, then, as a baseline, that we think that all people at age, let's pick 65, deserve to, if they want, leave the labor force and to live a decent life without having to work. Let's just take that as a baseline assumption. If we believe that, then first I want to ask you, what does it take to have that, and how far short do people tend to be falling of being able to live the rest of their life, from age 65 to their expected death, in a period of comfort without having to work?

Ghilarducci

Exactly. So, the question, I'll just restate it: If we all want to retire, how much do we need? How much does a person need? How much do they have, and how much money would government, or an employer or somebody else, need to fill the gap? Most people you know who are making minimum wages need about half a million dollars at age 62-63 to be able to retire. Say your annual salary is about $50,000. The rule of thumb is that you should have about eight to 10 times your annual salary at the time you want to retire in your mid-60s, in order to supplement Social Security, and you won't see a big change in your living standard. It doesn't mean you're going to be able to travel around the world or walk the Great Wall with somebody carrying your suitcase, but you will be able to maintain your living standard.

I always choke when someone asks me that question. I say, all you need is a half a million dollars. I know because of my data. I've turned it every which way, and I've looked at about five data sets that Americans don't have $500,000 at age 62. The only ones that even come close to that eight to 10 are the top half of the top 10%. Even people who are rich don't have that amount of money. And the bottom 90%, forget about it. The median amount for people in the bottom 50% of the income distribution, which means half the people, have nothing. Nothing. They don't even have $50,000. The next 40% who have earnings between $60,000 to $150,000 have $90,000 for retirement—not $500,000. So, the retirement system is a crisis for everybody. Low-income workers, who never had enough, still don't have enough, and they're going to be poor or near poor in retirement. The middle class people, the next 40%, have about 90% if they can work, and that's great. If they can delay collecting Social Security, that's great, but they're not going to be able to maintain their living standards. They may not fall below poverty, but they won't be able to maintain living standards. Even the top 10% have the worries because their retirement income is coming in the form of cash, in a lump sum, and they're really panicked about living too long. So, we have a wacky system for everybody, but it certainly is stratified. It makes the inequality we have in our society much worse. The government subsidies that go into the retirement system, $300 billion a year, go mainly to the top 10% and 20%. For the top 20%, it varies, but it's either 70% or 80% of their income. So, we're already spending hundreds of billions of dollars for retirement security that's not even touching the bottom 90%. All right, so what does it take as a society? We need to put everybody into a pension system on top of Social Security. We don't actually worry about incenting people with financial literacy and pamphlets and advisors to get into Social Security. It's not even a question. If you rent a room in your house for Airbnb, or you use your car to do Uber Lyfts, or you work as a lifeguard, like I did when I was 16, I got a paycheck and paid Social Security. I didn't have to be incented to sign up. I didn't have to opt in or opt out. I didn't have a waiting period. I just was in Social Security. If we had a retirement system that did just that, in which every time that I worked, I got a certain percentage, just say 3-5%, then we would have a population that could expect to retire, and we wouldn't have stories like that janitor at the Texas school where the 10-year-olds raised money for him to retire, or the news anchor was able to tell a compelling story about a 90-year-old in Louisiana.

Robinson

And it is possible. I'm from Britain, and my father--

Ghilarducci

I noticed it wasn't Louisiana.

Robinson

No, I live in Louisiana, but originally from Britain, and my father retired at age 50, I think, after 30 years working for a company in Britain, with a pension that he has now collected for 32 years, most of my life. He's done other work, but he's had that pension for the first part of his life.

Ghilarducci

Think of that. He had a base of income in which, after 30 years of work, he could live a whole other life. And people want that third age, as marketers call it, but it's not bad, and you need that. And also, in his occupation, 30 years was enough, and he probably wasn't an autoworker—

Robinson

He was in an aircraft factory.

Ghilarducci

He was close. He was making a vehicle. But you have workers that had enough power to be able to actually define what a working life was and what retirement was. He did start young. A lot of people don't start young. And he was the lucky one that he actually survived the job and had enough health to live another 30 years. But he didn't resent the fact that there would be a chance that he died in his boots, or that he died five years after. He was in an insurance pool, and that's what Social Security is. We have short livers and long livers, people with big families of dependents, and people that don't, but we pool it together. Now, our system of do-it-yourself retirement means that we have to put even more extra money and extra anxiety away to make sure that we can actually have enough money to live our lucky, long lives. It's as if we have a system where we all had to put aside $250,000 for that kidney transplant that we might have, because we all have to self insure for our longevity and inflation. But other countries don't do that. And in the past, when workers did have more power, or we didn't have this 401K revolution, we just had a societal acceptance that there was something called a decent amount of work, and therefore a decent amount of retirement, where we actually had a better, more efficient system.

Robinson

Yes, I think what's so valuable about what you do here is that you help to raise people's expectations of or understanding of what's possible. You point out the brokenness of the system, but you also very strongly argue it does not have to be this way. You lay out the planks of what you call a Gray New Deal, which is a rather charming name. And you point out that there are functional retirement systems around the world, it can be done. We don't have to have these ludicrous stories of people pushing carts at age 90 to eat. It's just frustrating, in part because it's so unnecessary. But to get past it does require getting past what, I think you say, is a big shrug and no outcry. And so, to get past the big shrug is seeing the way things operate and to denormalize it, in a sense.

Ghilarducci

Exactly. To lift up people's aspirations for retirement, I have to get past the big shrug of politicians and academics who say they could just work longer. And I have to get past the individual's shrug to say, I should have done better and not eaten so much avocado toast, or worse, a hang of the head, which is a representation of their shame that they didn't save enough. The problem with a DIY system is that you tend to blame the victim for not knowing how to do savings, finance spending, pick the right employer, pick the right parents, pick the right market, and avoid the recession. So, getting past that is to raise up the aspiration that we need something bold. That's why it's called the Gray New Deal. A New Deal means it's systemic, bold, and it takes society agreement. The Gray part is that a recognition of our humanness, that most hair goes gray. I didn't say silver, or any of those kinds of platitudes, just gray. Gray is good, and that brings some kind of pride in the human condition that we get older. With that pride, lack of shame, and this recognition that there is a technical fix to this problem, I then lay out my two planks. One is a nod to the American value. I'm not going to get rid of it. Other countries don't have it, but here we have it: if you want to work, you should be able to. We're the only country that actually bans age discrimination or mandatory retirement, and there's good and bad sides to it, as I point out in my book. The good side of it is that you recognize that an adult should not be banned from working if they want to. There's some dignity in being able to be able to work if you want. The bad part of it is that there's no legitimacy to have pensions because when you have mandatory retirement, you actually have pensions. And I talk a little bit about how the labor movement in our country and other countries never really was behind ending mandatory retirement. It was employers and other kinds of liberals in society, but it wasn't workers. Workers are the least uncomfortable with mandatory retirement in general, but I lay out very detailed ways to make older workers jobs better, and one of them is actually to have national health insurance, to bring our national health insurance, which, of course, is Medicare, and bring those eligibility ages lower so that it's easier for older people to get a job. Employers face big health care expenses when they have an older workforce.

But I really concentrate on the last part of my plank in the last part of the book, which is, what would a pensions for all look like? How could we engineer having everybody pay into the system starting the same time that they start paying into Social Security? And I'm actually realizing it's so simple that's a little embarrassing. A lot of my colleagues who are economists have these very fancy ways to restructure the world's financial system. Mine is not fancy. It's really common sense. Start early, invest it well, and then pay it out in a pension for life. It's what I hope that all workers have—the guy who drove me from the airport, the person who's going to serve me dinner tonight when I go out to dinner. Everybody should be able to have a pension alongside their Social Security. And I have to say this because we're nine years to insolvency with Social Security. Politicians should act now to put more revenue into Social Security, and the time is over to cut benefits. We can't raise the retirement age. That's just not a solution. This problem will get worse because of the magnitude of the numbers of people who will be old without enough money.

Transcript edited by Patrick Farnsworth.