Why You Should Read 'The Myth of American Idealism'

The message of Noam Chomsky could not be more urgent, and I’m proud to have helped him produce a new book.

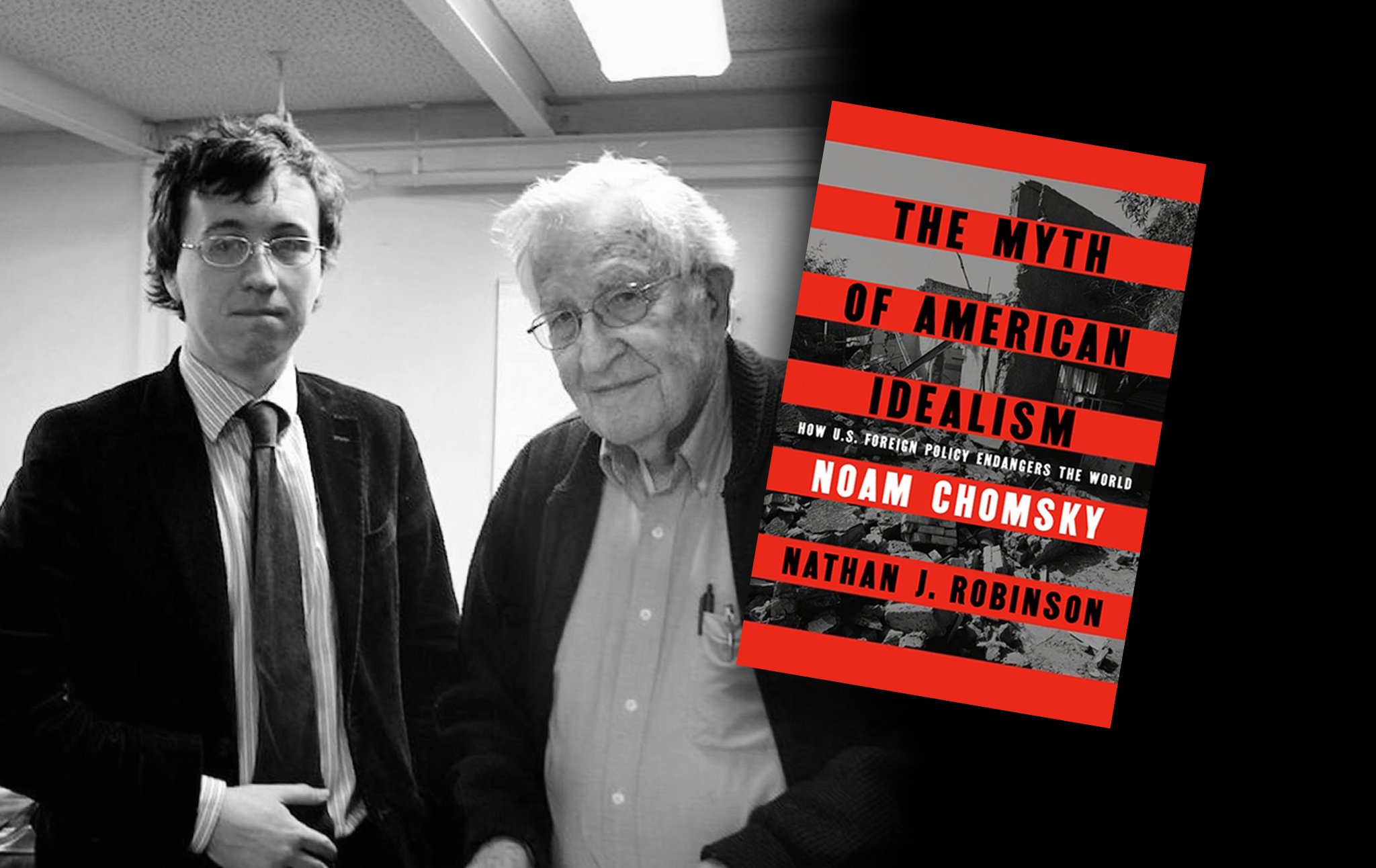

The Myth of American Idealism finally comes out this week, and I encourage you to pick up a copy (and of course, copies for all of your friends and relatives). It’s a book project I’ve been working on for years with Professor Noam Chomsky, whom Current Affairs readers will know has been a longstanding supporter of and inspiration for this magazine’s work. Chomsky was an early subscriber to our magazine, and like so many others I was able to strike up a correspondence with him, which led to two interviews and then to this book project. The book is a summary of some of the core ideas on U.S. power that Chomsky has been putting forward for over 50 years. It updates those ideas for 2024 and forcefully indicts U.S. foreign policy, arguing that unless we learn to see our own government’s actions the way others around the world see us, the United States is going to continue to pose dire threats to the peace and stability of the whole world.

I hope you read The Myth of American Idealism. It poses a powerful challenge to conventional wisdom. When I first read Chomsky in high school, it was an eye-opening experience. I knew at the time, for instance, that the Iraq war was wrong, and when George W. Bush came to town, I protested him. But Chomsky helped me understand why the war was happening, putting it in the context of a long series of U.S. attempts to assert dominance through force, which are often branded “well-intentioned mistakes” after they turn into catastrophes. Chomsky provided factual background that I had never been taught (such as the fact that the U.S. supported Saddam Hussein when he attacked Iran in 1980, after Iranians overthrew the brutal dictator we had installed to rule over them). He showed how propagandistic euphemisms were used to sanitize atrocities, and how crucial events (such as the bombing of Laos, or our repeated vetoing of a two-state settlement to the Israel-Palestine conflict, or our support for massacres in East Timor) were simply erased from standard U.S. history. Chomsky’s picture of U.S. conduct was dark and disturbing, but he encouraged readers like me to face the truth squarely and to accept that we have a responsibility as Americans to rein in our government.

Chomsky’s basic argument is often misunderstood or misrepresented as “anti-Americanism.” I’ve explained at great length before why this is an error. Focusing on the crimes of your own government does not imply a minimization of the crimes of other governments. It’s a point I also explained in a letter to the editor of the Irish Independent, which ran a viciously critical review of Myth. (The Progressive has now run a much more positive—and accurate—one.) The Independent reviewer didn’t identify any factual errors in the book, or even address our basic arguments. Instead, he accused us of being apologists for dictators, because we didn’t spend much time talking about the crimes of countries other than the United States. As I noted in my response, this is because the book is about U.S. foreign policy, not about, say, Syrian policy. But that doesn’t imply that we’re rationalizing the crimes of Bashar al-Assad, any more than writing a book about South Africa that doesn’t mention Argentina implies you’re fine with the government of Argentina. It’s a very childish objection, one so obviously incorrect that it seems like it must be made in bad faith. But it’s very common among Chomsky’s critics.

In fact, as you’ll see in the book, the argument in Myth is not that villains like Assad and Putin aren’t villainous, but that we should stop seeing our own country’s actions abroad as uniquely moral, because we too are responsible for heinous acts of violence. We rationalize these acts of violence with self-flattering stories, or simply overlook their human consequences. But to their victims, they are all too real, and Chomsky’s work has long demanded that we not look away from the ugly truth of what our country has done. Now, I should also emphasize that when we talk about what “America” or the “United States” has done, we’re not indicting all of America to the same degree. Much of the country’s population has no idea what its government does abroad, and would be horrified if they knew. We are talking about actions done by those with power.

The record is pretty bleak, from Vietnam to Afghanistan to Palestine, and shows the horrific human consequences of U.S. policy. We also warn that the deadliest threats to humankind’s future, climate catastrophe and nuclear weapons, are being made worse by the decisions of U.S. leaders. But even if the book is not an easy read in some ways (I keep trying to remember not to tell people that I “hope they enjoy it,” since “enjoyment” is an odd word for the experience), it’s accessible, clear, and not at all hopeless in its conclusions. In our final section, we discuss the history of protest movements that have successfully challenged those in power and made the world a much better place. We encourage our readers to believe in their own capacity to do the same.

Working on The Myth of American Idealism with Prof. Chomsky has been one of the highlights of my life as a writer. For a year we corresponded back and forth over drafts, trying to get something that powerfully articulated his views and restated the arguments with updated evidence. Unfortunately, toward the end of the process Prof. Chomsky suffered a major stroke, and I was left to finish editing the manuscript on my own. (Our Israel-Palestine chapter, for instance, ends in 2022, so I wrote a postscript under my own name that covers events since October 7 of last year.) That was a pretty heavy burden, because I wanted to make sure the final book did justice to Prof. Chomsky’s ideas. Fortunately, I was working with Chomsky’s longtime editor, Sara Bershtel of Penguin Random House, and together we were able to ensure that the finished book is highly polished, well-sourced, and clear.

I hope the book is good, but more importantly, I hope readers will grapple with some of the challenging ideas that have made Prof. Chomsky one of the most-cited and important living intellectuals and inspired countless people around the world. I hope it sparks debate and causes people to take seriously the central point of the book, namely the grave threat posed to the world by the U.S. effort to maintain global dominance. The facts laid out in the book are disturbing and in many ways terrifying, and my hope, one I know that Prof. Chomsky has long shared, is that the public will come to understand the danger that we are in and act collectively to radically democratize existing power structures.