Why People Feel Rotten About The Economy

Leading economics commentator Kyla Scanlon on how people's feelings matter in assessing an economy's performance.

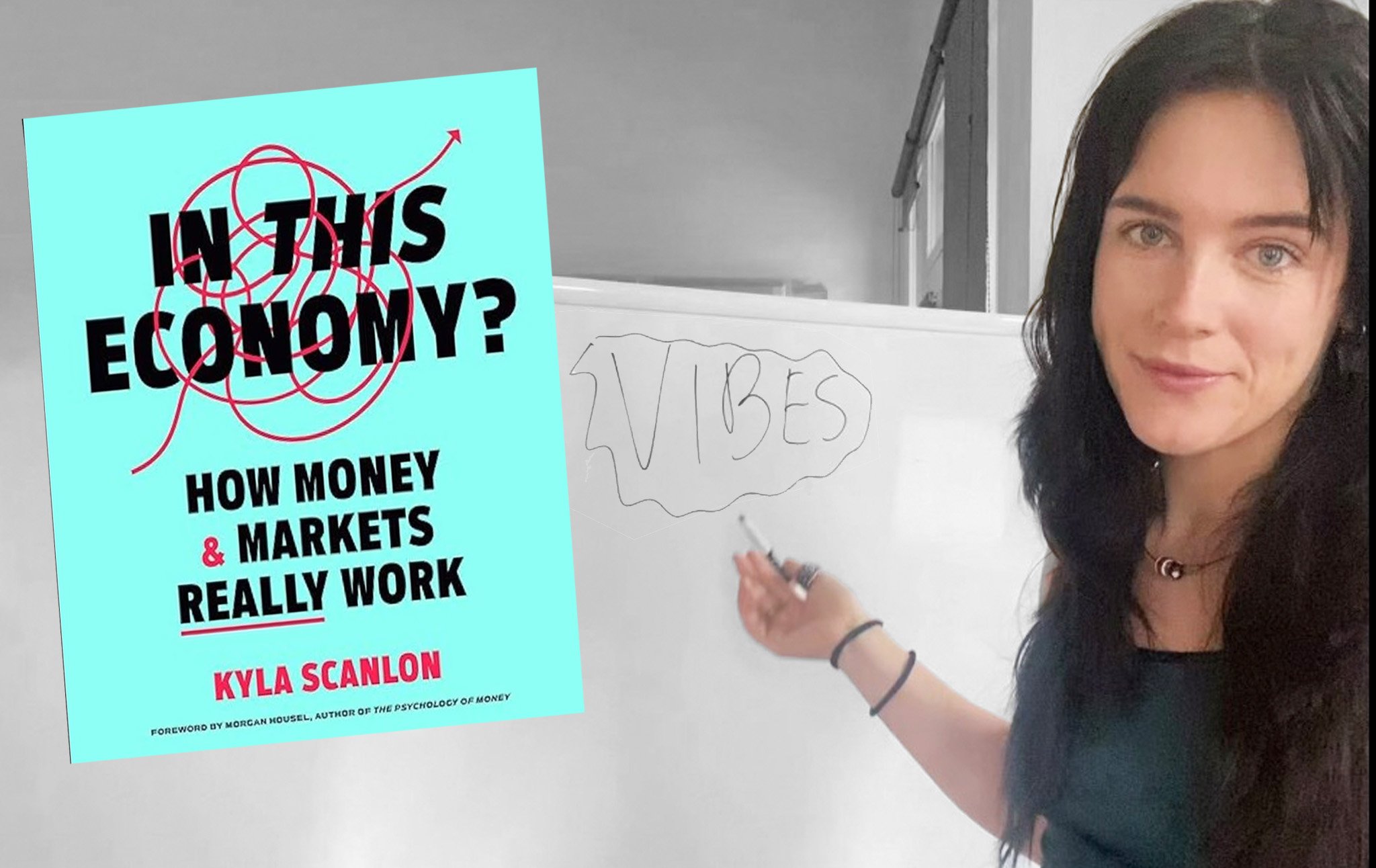

Kyla Scanlon is a leading online economics commentator and Bloomberg contributor who regularly publishes TikTok explainers helping people understand the economy. Her new book In This Economy? is meant to help laypeople understand the economic forces around them that are so determinative in the outcomes of our lives.

Scanlon coined the term "vibecession" to describe the disjunction between certain "objective" economic indicators and people's "subjective" feelings about the economy. Some people have theorized that the public is simply being misled by negative media coverage into thinking the economy is worse than it actually is. But as she explains in this conversation, it's not so simple to disentangle the "subjective" from the "objective" in economics, and just because the "vibes" don't match the standard predictions, doesn't mean they're illegitimate or unfounded.

nathan j. Robinson

I opened my copy of The New York Times this morning, and I saw something that confused me. Your expertise is in clearing up people's confusion. You write in the book that your aim is to have an economics education for all. So, I want to read to you what I read and what gave me a big question mark so that maybe you could clear it up: the government's monthly jobs report. It said, “sometimes the many numbers included in the government's monthly jobs report come together to paint a clear, coherent picture of the strength or weakness of the US labor market. This is not one of those times. [...] Reports showed employers added 272,000 non-agricultural jobs in May, far more than forecasters were expecting. The data from another survey showed that the number of people who were employed last month fell by 408,000 while the unemployment rate rose to 4%." Is this good? Is this bad? How does the ordinary person reading their newspaper see something like this and understand what's going on?

kyla Scanlon

Labor market data is super confusing. So, we actually got another labor market report earlier in the week called JOLTS, a Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey, and that also showed a slowdown in the labor market. So, fewer job openings, fewer vacancies, the quits rate—the number of people who feel like they can voluntarily leave their job—also fell, all pointing to a slowdown. But then we had this crazy print in monthly non-farm payrolls, which was this 272,000 number that you referenced, but also the unemployment rate went up, but also wage growth went up. And so, just to say that the labor market metrics are confusing right now is kind of an understatement. It's all pointing to a normalizing labor market, which is good. In terms of what the Federal Reserve wants, it's good. It's not good for people, but it's good in terms of monetary policy, which is ultimately probably good for people. But, yes, it's a super confusing time. There's a lot to be said about the way that we collect labor market data, that the data itself might have flaws within it.

Robinson

I bring up this particular example because a question that is often asked is, is this a good economy? Or is this not a good economy? This is sort of central to the unfolding presidential election. The Biden administration wants to make the case that we have a good and strong economy, and yet people don't feel it is a good and strong economy. And then there is an argument that all of those people are wrong. They don't understand that the statistics show that the economy is quite fantastic and that Joe Biden's done a very impressive job.

Now, you are well known in the economics commentator community for having coined a very special term: “vibecession.” In this book, you write about this thing that has had a lot of public discussion, which is this idea that there’s a disconnect between the feelings or vibes and various underlying realities. There's a simple argument which is made, which is essentially that things are good, and the media makes people think things are bad by telling them negative news. That's actually not the story that you tell in this book. In fact, you give a lot more credence to people's feelings. What you say is that finding out the answer to whether the economy is good is actually very difficult.

Scanlon

Yes. It's so confusing. And just to caveat everything I'm about to say, the economy is a very personal experience. All of us have our own personal inflation rate. All of us have a personal experience with the labor market. All of us have a personal experience of economic growth. But we talk about the economy in terms of averages and medians most of the time, so we're not necessarily talking to everybody's personal lived experience. But the idea of the "vibecession" is this large disconnect between consumer sentiment and economic data. People are feeling way worse about the economy than we'd expect them to, relative to where the metrics are. And so, yes, the economy is confusing, it's weird, and it feels weird to be a part of it, but the metrics are still somewhat okay. The labor market is okay, the economy is growing, inflation is going down, yet people are still feeling bad. And the point that I try to make in the book is that people feel bad for good reasons. We have structural affordability problems and crises with housing, healthcare, elder care, child care, all of these different things specifically in the United States. And so, it makes sense you would feel bad, and we have to pay attention to how people feel because those expectations, oftentimes, ultimately end up dictating where the economy goes. And so, there can be a disconnect, but there's going to be a convergence at some point between the two, between consumer sentiment and actual data.

Robinson

One of the reasons I think I feel bad—because I do feel bad, and I don't feel particularly reassured when I see inflation is under control—is that there's a massive heat wave in many parts of the country and temperature records are being broken. I feel bad because I'm afraid about the future because I see the climate crisis is very real. I don't know what it's going to look like in 20 years, but if it gets hotter and hotter every year, it scares me. Can you talk a little bit about the role of fear and expectation in driving people's understanding of how things are?

Scanlon

Yes, a couple of things. Climate change is real, and it is really concerning. California could fall off into the ocean in a couple of decades. There are really big things to be worried about here, and I think that people are sort of pricing in that fear to the present moment. This is actually the media point: we consume so much information about all the bad stuff that's constantly happening, whether it be climate change and people who aren't able to find jobs, which is a lot of people right now, or whether it’s news around the presidential election and geopolitical conflicts. It's consuming us all the time. I also think there are really big things to worry about. And the usual solution, or something they would say is if people feel there are so many things to worry about, is that we'll fix it eventually. And in the book, I do talk about the opportunities that we have to fix things. But I think another big reason why people might feel that way is because it feels like, even with all the opportunities that we have to fix things, there are all these roadblocks. And I'm sure you saw the governor of New York block the congestion pricing tax, and that's another example of stuff we can fix that gets stopped right at the finish line. So, is there really anything to hope for? I guess my answer to your question is, yes, we should worry about the climate, we should take better care of the Earth, and we do have the opportunities to fix these things, but it totally makes sense to have a headache because it seems like every time we get to the finish line to fix something, it gets stopped in many cases.

Robinson

With this question, “why do people feel bad?” I think about my parents. They live in Florida, and one of the reasons that they feel bad is there are more houses in designated flood zones, and property insurance is going up because hurricanes are worsening, and the threat of them continuing to worsen is growing. Meanwhile, the governor of the state of Florida has just started to strike all references to climate change from state laws. I do think it’s that thing that you say, that sense of powerlessness, that sense that even if we have solutions to our problems—I don't think my parents feel like there's any prospect of not living under a Ron DeSantis administration in the near future. But what's interesting to me is that's non-economic. That's not a piece of economic data, but it would factor into, I think, how they would respond to a poll about the economy.

Scanlon

Yes. The economy is holistic. So, I have a lot of poems, literature, and philosophy throughout the book. Economics largely is influenced by politics. When we talk about a housing crisis, that will be solved by policy and by politics. It's going to be solved by incentives for whatever in the free market to do certain things. Economics and politics are wholly intertwined. The number one thing that people worry about when they go into an election is the economy. And so, I think those two things are very similar because politics influences how people experience the economy.

Robinson

You not only have poems and literature here, but you also have drawings. Before I ask you another economic question, tell us about the drawings.

Scanlon

Yes, I did them. I have a newsletter as well. It's kyla.substack.com, and for the past three years, I've drawn most of my newsletters. I have drawn a little diagram to go along with it. I'm a visual learner, and I think having pictures really helps. And the goal of the book, and the reason I included illustrations, was to make economics accessible and fun. It doesn't have to be this really dry, boring thing. That's not the way that you're going to get people to read a book about the economy. So, yes, there are 60 illustrations in there. Some of them are an attempt to be funny, but it was my goal to make it more accessible and fun.

Robinson

Yes, I think that's important. To get back to feelings, which are sort of at the center of your book, I think one of the reasons that people tend to feel bad, or a way in which people can feel bad, is this sense that they don't understand the forces that are controlling their lives. They feel powerless because they read that the Fed increased this rate, and they think, I don't have any idea what's going on—I know this is affecting me, but I have no comprehension of it, and I have no ability to control it.

Scanlon

That's my main theory with writing the book: I experienced this. When I was in college, I was like, what is an economy? I don't understand what's happening. I was in college in 2018-2019 and that's when the Federal Reserve was trying to reverse one of their monetary policy decisions, and the market freaked out. And I was like, what is the Federal Reserve? And so, I ended up majoring in finance and economics to try and figure it all out. But I totally felt that. If you feel disconnected from the system that you're a part of, it's really hard to not be confused by it. And so, the goal with the book was to give people the toolbox that they need to understand the world around them, and then hopefully they'll make better decisions because at least you'll have knowledge of how the Federal Reserve raising rates impacts mortgage rates, or knowledge of how GDP growth could impact your job prospects, or just knowledge of how we measure the labor market and the flaws in measuring it. I think it's our civic duty to understand the economy. I think it helps to create better voters and helps create a better society.

Robinson

One of the nice, reassuring things about your book is the extent to which you point out that there are things that nobody understands. In fact, you have a whole section where you talk about economic theories. There are theories that have seemed very sound and that have had very strong arguments and a pile of statistics behind them, and then all of a sudden, something happens in the world, and the theory that many economists are completely confident in collapses or needs to be revised, or has been opened up for debate again.

Scanlon

We saw a total breakdown of a lot of the economic models after the pandemic. The Phillips curve is one key example. The way that we thought things were wasn't how they worked. If supply chains are broken, if the Federal Reserve is massively cutting rates to try and get people to be okay, but they're also locked inside—everything just changed because we had a totally different economy.

One of my favorite fun facts is that nails (the nail part of a hammer) used to be 0.5 percent of GDP in the late 1800s. And so, that was a totally different economy that probably was sort of similar in terms of economic theory, but you have to think about that economy as massively different from the economy that we have today. One of the things I try to thread throughout the book is that nobody knows what's happening, but you can at least kind of understand.

Robinson

You repeat several times that people are the economy. You talk a lot about subjectivity and the role of subjective assessments in producing objective reality and the way that the stock market is massively affected by vibes, or what Keynes called the “animal spirits,” and I think you also use the term “weird” several times to describe how things work.

Scanlon

Yes, people don't like the usage of the word “weird,” it turns out. I've gotten some angry emails about that, but I think it's right. I do think some of the stuff is just weird, and that's probably the best word that we have to describe it. But I do think the point of animal spirits is really just that people are the economy, and human behavior ultimately ends up influencing actions. A lot of really smart economists have worked on this for a long time, and they're right in some aspects, but much of the basis of economic theory is "rational people," and people are kind of irrational. And so, that's the idea of Keynesian animal spirits. George Soros’s “reflexivity” is sort of in that same boat, that human behavior will ultimately drive action. And that's, I think, what we've largely seen in the economy and now definitely in the stock market.

Robinson

I interviewed a few months back your Bloomberg colleague Zeke Faux. They have a wonderful book on cryptocurrency called Number Go Up. We talked about the Bored Ape NFT thing, and I still couldn't understand why anyone would pay any money for these things. But people's belief in the thing's value really determines the value. There is no objective source of value. If people think the apes are worth money, well, they're worth money.

Scanlon

Yes, Roaring Kitty of the Gamestop saga did a live stream on Friday, June 7. The only reason that Gamestop has any value is not just because of him, but it is largely because of him. People are choosing to believe in Roaring Kitty and not necessarily in Gamestop as a company. So, it's very similar to the Bored Apes world, which is sort of predicated on this idea of scarcity, some element of status, and some element of belonging. You go to Bored Ape Yacht Club or Gamestop to find a sense of community, and you're paying up for that, and people are expecting that community to appreciate in value, which is kind of funky, but that's how I think about it. It's people paying for friends.

Robinson

Actually, you mentioned community elsewhere in the book. You talk about loneliness and alienation and the lack of what are called third spaces, places where you can go and don't have to spend money and hang out with people. It’s interesting to read in a book of about economics about loneliness and just general sadness. It affects how people are going to answer a poll on how they think the economy is doing. Because it would be weird to answer, I feel terrible, but I think the economy is great. These things are going to feed into each other.

Scanlon

Yes, and it's actually the opposite. It turns out a lot of people say, I'm okay. Seventy percent of people feel fine about their personal financial situation, and only 30 percent feel fine about the economy at large. But to your point on loneliness, you're exactly right. Being lonely is going to impact how you feel about the economy. It's going to impact how you feel about everything. And so, going back to the point of trying to make the book holistic, that was my goal. We have to discuss the societal pressures that are weighing on the economy. We can't just pretend the economy is being dictated by big, giant corporations just making money and selling stuff. It's really the people and how the people choose to buy things and how they feel about their circumstances, and if they feel like they can move and can invest in the communities around them. That's ultimately dictating our path of economic growth. And you can point to AI and crypto perhaps as the true drivers of economic growth in terms of dollars, but these are the people who are moving the momentum.

Robinson

That statistic that you mentioned, that people are feeling kind of okay about their personal finances, is really interesting. As you mentioned, there are all sorts of deep structural problems, like the cost of healthcare and housing and the lack of parental leave, but as you said, people feel relatively okay about their personal situation, or at least more okay than they do about the economy. You talk about the power of narrative in shaping perception. Now, this is why some people blame the media. To come back to the election, what Joe Biden is now doing is trying and make an argument that people should feel better about the economy than they do, which is a really hard argument to make because to say that you're wrong about your problems is not a winning message. I wonder if it's not just the media, but it's also just that this is a way in which Biden's age might affect people's perception of the economy. People like to measure what they think the economy is by whether the president seems like he's doing well.

Scanlon

Sure. I think the Biden administration passed a lot of good stuff, like the CHIPS Act, the IRA (Inflation Reduction Act), and the IIJA (Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act). Those are all impressive things. With the CHIPS Act, we're going to have a bunch of manufacturing of technology here in the United States, which is good if you're a fan of reshoring, but also it's just good in general. And then the IRA basically got us through some tough parts of 2021 and 2022. And so, I think that the administration has just done a really bad job at signaling what they've accomplished. I also think people are maybe having a hard time hearing them. There was a very good piece from Kate Aronoff called "The Case for Pool Party Progressivism," and it was this idea of, yes, we've invested a bunch of money in manufacturing good, but the average American doesn't feel that. And so, the Biden administration has focused on the individual, but they should have probably done more messaging around what they've done for the individual, versus having all this focus on manufacturing and what was happening there because I think many people just feel left behind by the policies. Of course, the student loan debt crisis didn't really help things. There's just been a lot of political tension. And I do think the age is such a big factor. Many people don't want either Trump or Biden running. They're both terrible candidates, potentially, and it'd be great to have somebody else in there. And I think that statistic gives you a summary of how Americans probably feel. To your point earlier, they probably do feel powerless.

Robinson

I haven't met a single person who's felt satisfied with their options in 2024. I've met people who say, it's very important to vote, vote for Biden. Nobody's particularly satisfied. And dissatisfaction with your political options could affect how you perceive whether the economy is good because people just use economy—economy is a difficult word. I don't feel dumb asking this question, because you said you asked this question, but what is an economy anyway?

Scanlon

It's the movement of goods and services between people and businesses. At the beginning of the book, I have the circular flow diagram that demonstrates that a little bit more. But yes, I think the economy, much like inflation, has just become this big word that people use to talk about different circumstances. They'll say, the economy is really bad, but they're referring to the cost of a box of cereal, and that's not the economy, it's part of the economy. But I think we oftentimes will look at one component of something and say it's the fault of the entire economy, versus pointing out that it's an individual experience within the economy.

Robinson

You point out that gas prices play an outsized role in people's perception because they're on a big sign, just standing over you. A number on a sign is a very accessible metric.

Scanlon

Warning, personal opinion: car culture in the U.S. has also made the gas price on every street corner really bad because people are stuck in their vehicles during rush hour looking out, and all you see is tough economic news. I'm sitting in traffic; I'm stuck in my car; everyone else is stuck in their cars; gas is really expensive, and I'm sad about that, and I'm stuck in my car. So, I just think with car culture, the gas price is on every street corner, flashing and telling you it's expensive to be alive. It's tough. It's really tough.

Robinson

We recently did an interview with the author of a book called Carmageddon. It's a very anti-car-culture book. One of the central points that came out of that book was about the loss in quality of life that comes from sitting in your car all day from long commutes. And I think one thing that might influence people's assessment is the sense that things could be better, that we could have more. You point to the staggering gap between how well people at the top did during the pandemic and how people at the bottom did. There is frustration. You had this crazy statistic in there that "if income growth since 1975 have remained as equitable into the 2000s, aggregate income would have been $2.5 trillion higher, equating to roughly $1,000 a month average increase in the ordinary person's pay." So, that gap between what you could have and what you do have.

Scanlon

Yes, totally. And I think people feel that. So, since the pandemic started, lower wageworkers have experienced the most income growth out of all the income quartiles, but you still feel like you're left behind because of inflation, because of tensions in the labor market, because of political nightmares. And there's a really good saying, and I can't remember who said it, but it was essentially that America has a lot of wealth, but it doesn't have a lot of prosperity. I think that's what we're seeing with this wealth inequality issue. Sure, incomes have ticked up, but also, it’s just hard. We have a housing crisis, we have all these structural affordability problems. Things can be getting better, but that doesn't always mean that they're feeling good. And I think also, a lot of the frustration after the initial pandemic years was that people saw what the government could do. We saw that the government could do stimulus checks, rent forbearance, and pause student loans, and then they were like, never mind, sorry. Part of that made sense, but I think many people thought, okay, you can help, and you don't, and that's really frustrating as somebody who's part of a voting base. You think, what am I doing here?

Robinson

When people get a taste of the good life, their expectations might increase, or their sense of what's possible. That's an interesting point because as your sense of the possible expands, your level of frustration with the current situation also increases.

Scanlon

Yes, true.

Robinson

At the end of the book, you have some of the key policy interventions that you think would make the economy work better. So, where do you think we start? At the beginning, you use the metaphor of a kingdom. So, if you were put in charge of the economic kingdom, and you were the reigning absolute monarch, and you're told your subjects feel bad, and you keep pointing to the chart that shows that they've got inflation, and they still feel bad, what do you do?

Scanlon

I actually have spent a lot of time thinking about this. One thing that's become frustrating in my own life is I felt like I was spending quite a lot of time talking about problems and not about potential solutions, but I really do think it's an element of messaging. So, I would make it so that media headlines cannot be sensationalized, which would make the media business a little bit hard, I think. But I think that would do a lot of work, but of course, would not work at all. I also think that there has to be some sort of messaging about a social safety net. This is an unpopular take because people are like, what, do you mean you want to help people out and give them money? But I do think that some sort of social safety net, whether that be just something to help people when times are tough, or just to get them through certain things, would be extraordinarily beneficial.

I also think that there needs to be an increase in trade schools, and training up in trade schools. There have been many bottlenecks there because of a lack of training. I think those are some of the top things. I think we need to reform immigration. We really need to message that better. What does it look like to bring high-skilled immigrants in, and how can that help grow the various economies? I think we really need to figure out the cost of college education. There's a lot of bureaucratic bloat, and I think that's instilling a sense of nihilism in the younger generation. If you're 18 years old and signing on a huge loan for $250,000, of course you're not going to feel like money is real or that you have a future. And so, those are just some of the things that I would start with. I'm sure they're so politically feasible, I'm sure there would be no problems making any of those work. And I also would have congestion pricing in New York City.

Robinson

Yes, which was so tantalizingly close to being real. Well, one of the things that comes from In This Economy is how our money and markets really work. One of the things that is good about economics education is that it does immunize you to propaganda in a certain sense. You just mentioned immigration, and it's very easy to tell people a story that says more immigrants means lower wages for you. Supply and demand: that is economics, and it can sound very compelling, but what you say is, actually, the world is complicated. Let's think about this.

Scanlon

Yes. There's a study out of Ohio that showed that if you allowed high-skilled immigrants in, it vastly expanded the state's GDP. It rebuilds elements of local communities, and it didn't really take away anybody's job. It just added more jobs. For whatever reason, maybe it's American individualism or a net negative mindset, we think that the pie is limited. We believe that only certain people can have a certain piece, and if more people come to the table, there's not going to be enough for you. But the thing about the economy is that the pie is ever expanding as of right now, and so we can continue to grow the pie. It doesn't have to be something that only certain people can benefit from.

Robinson

I just want to conclude here with another thing you say here that might irritate some economists, which is that at one point you ask the question, isn't this a book about economics, not astrology? But then you argue that the two have more in common than you might think, and you also say that people call economics a dismal science, but it is a fact closer to a dismal art. Defend that controversial opinion.

Scanlon

Okay, thank you. So number one, I just want to address that this book is a consolidation of economists everywhere. I think economists are so smart, and this book is meant to be a compilation of all the brilliant work out there, but I do think that economics—more so because all the theories are kind of falling apart—has really become like looking at the stars and trying to predict what's going on. Even with what's happening with the European Central Bank and the Bank of Canada cutting rates, they're kind of like, we're not going to follow a rate cutting path, and we're just doing this for now. That sort of goes against economic theory in general, but it really is kind of like a vibes-based economy, in the sense that you're reading the tea leaves. The data points, and people, are a little bit funky because of COVID. And so, that's why I would say economics is similar to astrology, similar to an art, because people are involved, and therefore it's hard to make purely mathematical decisions about what to do.

Robinson

You even have, on page 224, the legendary Milton Friedman, winner of the Nobel Prize. You discuss monetarism and the emphasis of control of the money supply. And he said, inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon. And you said, however, this is wrong.

Scanlon

It is wrong.

Robinson

But if you can't trust that guy, who can you trust?

Scanlon

That's the thing. Inflation was a supply and demand problem during the pandemic. So, sometimes it's a monetary phenomenon, but not everywhere and always. And so, I think that's the thing. One of my favorite things to spout out right now is nuance doesn't sell, but you have to be nuanced when you talk about the economy.

Robinson

Yes, if you don't want to embarrass yourself like Milton Friedman, you might want to avoid phrases like "everywhere and always." If there's one takeaway I got from reading In This Economy, it's that “everywhere and always” is something you probably don't want to say about a world as weird as the world of economics.

Scanlon

Yes, it was very bold for him to say that.

Transcript edited by Patrick Farnsworth.