What the US Did to Haiti

How the American public's ignorance of the country's destructive policy towards Haiti fuels racialized narratives about the supposed threat of Haitian immigrants.

Donald Trump and J.D. Vance have recently been pushing vicious racist fake news about Haitian immigrants in Springfield, Ohio, claiming they are stealing and eating people's pets and destroying the town. But why are there Haitian immigrants in Springfield, Ohio, in the first place? What role has U.S. foreign policy played in driving Haitians from Haiti? Jonathan Katz is one of the leading journalists writing about U.S. imperialism and is a specialist in Haiti. The former Port-au-Prince bureau chief for the Associated Press, he is the author of the books The Big Truck That Went By: How the World Came to Save Haiti and Left Behind a Disaster and Gangsters of Capitalism: Smedley Butler, the Marines, and the Making and Breaking of America’s Empire. Katz tells us about the history of U.S. relations with Haiti, common misconceptions about the country, and the deeper meaning of the Springfield pet-eating scare and how it fits with longstanding racialized narratives about supposedly threatening Haitians.

Nathan J. Robinson

You were the number one person I wanted to talk to, having seen the recent eruption of horrendous fake news about Haitian immigrants in Springfield, Ohio. It is now reported that, thanks to Donald Trump and his running mate, J.D. Vance spreading the false story that Haitian immigrants are eating people's pets—Donald Trump said this at the debate—more than half of Trump voters believe Haitians are eating people's pets. But even people like Marianne Williamson have said that we have to take this story seriously because Haitian Vodou is real. I wanted to talk to you because I thought, I know who's probably having very strong reactions right now—of all people, it’s Katz. Can you tell me first what your immediate reaction to all of this was?

Jonathan M. Katz

I can't. It is sickening. It is dispiriting. It is unsurprising in a lot of ways—Marian Williamson, maybe, is a slight exception to that, although maybe not—but it is coming from people who say and do extremely hateful things on a fairly regular basis. But my god, it's awful. It's just absolutely sickening and awful. Honestly, that's my visceral reaction to it.

Robinson

Stories or myths about immigrant groups eating people's animals and doing various things are very common. In England, it's said they're eating the Queen’s swans, and it's always a different immigrant group. It's not necessarily Haitians, but there is also a Haiti-specific element of it that you can hear in what Marianne Williams said there that, well, Haitian Vodou is real. And so I wanted to talk to you because it also seems that there is a special American ignorance and blindness about Haiti, that you have spent a large portion of your career trying to correct, is there not?

Katz

Yes, you're touching on all of it here, and there's some other, even deeper, I think, economic things that we can talk about later on. But as you say, this is very common agitprop against immigrants, whether it was Chinese immigrants in the late 19th century or today, or, as you said, in England there were articles in The Guardian over the last 20 years debunking claims that Eastern European refugees were eating all the carp in England and how English fisheries were more worried about Eastern Europeans eating all their carp than the loss of fish populations due to overfishing and climate change. And the thing that you're noting here, which is very correct, is that there's a particularly gross, insidious, and pervasive anti-Black and anti-Haitian element to this. It's not an accident that they are focusing on Haitians in particular. Part of it is because, just in terms of proportions, basically because of a slight tapering of immigration from Central America, from the Northern Triangle, over the last three to four years, Haitians, Venezuelans, and Cubans, to some extent, are making up a larger proportion of immigrants coming into the United States. So in part, it's a reference to that, but there's also something very specific about Haiti in the American consciousness and the American imagination—

Robinson

That goes back a really long way.

Katz

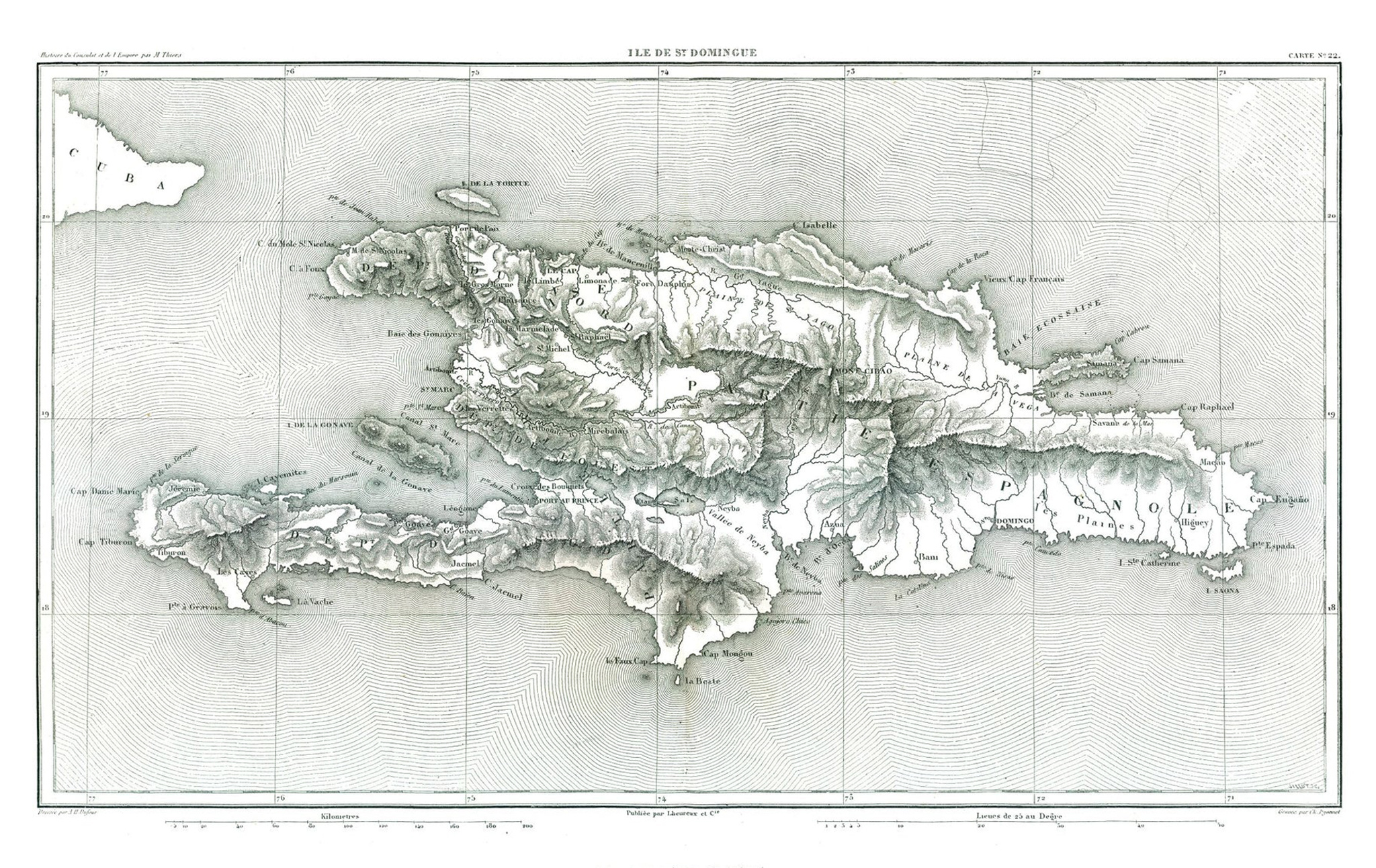

Yes. It goes back to the Haitian Revolution, from 1791 to 1804, which is a seminal event in Western history. It's the only time in the modern world that a country was forged out of a successful revolution by enslaved people against their masters. Haitians rose up and freed themselves from slavery. They freed themselves from French colonialism. They won their independence. At various points along the way during the Haitian Revolution, they got some help, actually, from John Adams's administration, basically because it was going to be good for some of Adams's constituents in New England shipping to continue running their ships to Saint-Domingue, which is the colony that becomes Haiti. But from the moment that Thomas Jefferson, himself a slave owner, comes to power in 1800, which is in the middle of this revolution and Haiti wins its independence while he's president, American politics is seized by just terror at the prospect of Haitian revolution happening in the United States.

Robinson

It's amusing how they're afraid. They're deeply afraid of Haiti.

Katz

Yes, and with reason, to some extent. At the beginning of Haitian history, it was trying to export, to the extent that it could—it didn't really have the capability of doing much—its brand of freedom to other parts of the Americas, most notably Simón Bolívar. He was, in some ways, the George Washington or the Toussaint Louverture of the revolutions in Spanish America against the Bourbon Spanish. He went to Haiti and got training and arms. He sewed his flag of Colombia, which was known as the flag of Gran Colombia, in Jacmel, Haiti. In the United States, there were a number of uprisings by enslaved people that were directly inspired by events in Saint-Domingue in Haiti. When John Brown was in prison waiting to be executed, his jailer reported that he was reading a biography of Toussaint Louverture, who was one of the leaders of the Haitian Revolution. So there was reason for them to think this. But obviously the politics of it were extremely bad.

This then feeds into U.S. foreign policy in the 20th century, and the U.S. occupies Haiti from 1915 to 1934 and then continues roiling and underwriting coups and invading Haiti ever since, up to the present day. Right now, there is another doubly outsourced mini invasion of Haiti. It's actually Kenyan soldiers on the ground, but the idea for this was raised by the United States, which then went to the U.N. The U.S. had outsourced its previous intervention in Haiti to the U.N., the one that you mentioned from 2004 until the 2010s, and then the U.N. outsourced it further to Kenya. So this idea that Haiti is a source of contagion, that Haiti is a threat, continues to this day.

I should note Vodou, which is a real religion, plays a role. The mythological version, or the demonized version of Vodou, plays a major role in American imaginations about the whole thing.

Robinson

Tell me more about that.

Katz

So Vodou is a real religion. Generally, it's classed as a syncretic religion that combines elements of African worship, an African pantheon from West Africa, as well as elements of Roman Catholicism. There's a similar religion in Benin, in West Africa, which is known as Vodún, which shares some elements in common. But in Haiti, it takes on its Haitian form, which is both of a remembrance of Africa and also a remembrance of the trauma of forced removal from Africa. So in Vodou ceremonies, oftentimes the first god or the first spirit, or lwa, who is invoked is Papa Legba, the master of the crossroads, who basically travels under the Atlantic Ocean and then unlocks the portal, basically, between the gods of Africa and the worshipers in Haiti to then come down and be venerated or engage in spirit possession, which is something that you also see in Christian sects, especially Pentecostal.

Anyway, all that's to say, there's a lot of different aspects. There's spirituality of connecting with ancestors. What it is not is devil worship. It's not dark magic, and it is nothing involved with stealing people's pets. But Americans became aware of the existence of Vodou throughout the 19th century, as Haiti was being demonized, and so you've got this very African form of worship. A lot of the gods in the Vodou pantheon come from Africa. The syncretic part is that they're often venerated using Roman Catholic icons. So you'll have a Roman Catholic icon who has something in common often—for instance, St. Michael, who's in armor, is often venerated as the warrior god Ogou—things like this. But Americans became aware of this in the 19th century, and then really become extremely aware of it during the US occupation, like I said, from 1915 to 1934. There's a huge insurgency against, effectively, American colonization of Haiti, and among many of the insurgents, they practice Vodou. A lot of elements of Vodou, a lot of elements of Haitian religious and folk culture, end up getting lifted by the Marines and by American journalists who go to Haiti to cover the invasion and the occupation, and they get marketed back into the United States.

One of the most significant ones, by the way, is the zombie. Zombies are a distinctly Haitian creation. It's actually a way of processing the remembrance of slavery, because the Haitian zombie is essentially the worst kind of slavery. It's slavery that continues after you die—even death doesn't emancipate you. And then Americans take that, market it, change it around. For the first couple decades, zombie literature is a very racialized thing. It's really a fear of Haitian zombies, of Black people coming to America, to white civilization, and doing things. But all of these things are kind of all mixed together.

So it isn't surprising to have somebody like Marianne Williamson access Vodou and sort of American pop culture demonizations of this religion—it's African, it's foreign—and just sort of take aspects of it, or not even real aspects of it, just imagined aspects of it. There is animal sacrifice in Vodou. It's generally goats and chickens and things like that.

But animal sacrifice was historically part of Judaism as well. I'm Jewish, and we still talk about animal sacrifice. We don't do it because the temple was destroyed, but we talk about animal sacrifice and the memory of animal sacrifice in reading the Torah and then Jewish religious services. The difference is, in Haiti, they still do it, but again, it is not stealing people's pets to do so.

So what you're doing there is you're taking a sensationalized, demonized, and stigmatized understanding of a religion, you're applying it to all Haitians and sort of mixing it all together and then using that as an excuse for racism. And not all Haitians practice Vodou. In fact, some Haitians are adamantly anti-Vodou, especially people who are evangelical Christians.

Again, to talk about antisemitism in Europe, that's a very old story with Jews as well: taking elements of Judaism and using it to demonize or fearmonger about Jewish people, about Muslims, about Christians in many parts of the world. This is a thing that happens a lot, but it also happens with Haiti.

Robinson

You've talked about one variety of American ignorance of Haiti and its people, that it exists as this kind of terrifying dark place that threatens to infect the United States and this bundle of stereotypes that we have. Another part of the ignorance you've mentioned is the various ways in which the United States and U.S. foreign policy have affected Haiti's destiny, things that we just have no awareness of. You mentioned the occupation, and in Gangsters of Capitalism, you have the vivid recounting of the robbery of Haiti's bank, where they just land and steal all the money—things we don't know. Until the New York Times did that big thing on it a couple of years ago, I think there was almost no knowledge of the massive debt. I think a lot of people, when they read about the debt that Haiti owed to France, went, Haiti owed France money for having been liberated? What?

Katz

And then U.S. banks basically took on the debt, which was part of the cause of the invasion of 1915. It was to ensure debt repayment at the behest of Citibank specifically.

Robinson

So tell us about how we've affected Haiti.

Katz

To use a much more recent example, the earthquake that struck Port-au-Prince in January 2010, in the aftermath of that, the response was led by the U.S. military in the initial stages. The response was, effectively, geared not really toward reconstruction of people's homes in Port-au-Prince. People said at the time that perhaps this could be a macabre opportunity for—

Robinson

“Build back better.”

Katz

Yes, exactly, literally “build back better.” That's literally where it came from. That's where Bill Clinton started using it—he had been using it before that in Aceh in Indonesia, but he really made it his motto in Haiti, which really drove me crazy when Biden adopted that. I was like, do you not know? I do not know how this phrase has come to you. But yes, it could have been an opportunity to actually “build back better,” to do improved urban design, to do improved earthquake-safe homes and things like this. But instead, almost all the money and almost all the effort was put into building garment factories. It was this very neoliberal theory proposed by Paul Collier at The Economist in particular and championed by people like Nick Kristof, that basically the way to save Haiti—people are always trying to save Haiti; there's a saying that Haiti's chief export is redemption—is to put Haitians to work in garment factories.

It's very hard for the outside world to see Haitians still, 220 years after their ultimate self-liberation, as anything other than cheap low-skilled labor that could do things for us, for the "productive global economy." And so hundreds of millions of dollars are poured into a garment factory industrial park in the north of Haiti, far from the quake zone. And to get that project moving, there's an election in 2010 in the aftermath of the earthquake.

The way that election worked was, there were something like 18 to 19 candidates, and the top two, assuming nobody got 50 percent in the first round, would go to a runoff. And the two who were going to a runoff were basically the candidate of the then president's party—a guy named René Préval was the then president of Haiti—and a former first lady of a former briefly serving puppet president of a U.S.-backed coup government. Obama was US president at the time, and Hillary Clinton was Secretary of State, and they were really pissed at the president of Haiti, René Préval. They blamed him for the slow pace, as the saying went, of reconstruction up to this point. They thought he was making them look bad because he was slow playing a lot of these projects. He wasn't really. He's a nationalist, he's somewhat left-leaning. He was a former ally of Jean-Bertrand Aristide, who was a slightly more at least redistributionist, pro-poor president, who'd been overthrown twice, and once restored—all three times by the U.S. effectively. And Préval was slow playing these plans, and the Obama administration was pissed at him.

And there was this other candidate, a guy named Michel Martelly, “Sweet Micky,” a pop star. He's the star of Haitian Kompa music, just sort of like good time dance music, and he was running. [...] He had some connections to people who had been in John McCain's campaign in 2008. And Sweet Micky is seen as a pro-business president, somebody who is willing to sort of say the line, “Haiti is open for business now,” which was what the Clintons particularly wanted. Hillary Clinton goes down in early 2011 and says, we think there's been fraud. They can't really specify what the fraud is, but they say they think there's been some fraud in this election, you have to redo it. You have to take Préval's candidate out, a guy named Jude Célestin—you have to take him out and put Sweet Micky in. It's a little unclear whether she thought that Sweet Micky would ultimately become president, or maybe former First Lady Mirlande Manigat, but regardless, they just didn't want Haitians to have a free choice of who their president would be. And what ends up happening is Micky—Martelly—wins. He declares at his investor ceremony, Haiti is open for business. He says it in English, which is not the language of Haiti. He greenlights all the projects, and spends basically the next five years allowing these projects to continue. The projects go nowhere, which we could talk about the reasons why, but it doesn't even really matter for now. He was just being extremely corrupt, stealing all of this money that had been flowing specifically from Venezuela that was given as credit on petroleum sales that were deeply discounted, and that everybody was assuming was going to have to get paid back because Hugo Chavez was going to live forever, and the money was never going to be due, and then ultimately it comes due.

Then there were a bunch of investigations, and it was shown that Micky had taken a lot of it. And then Micky taps a nobody, this person nobody had ever heard of before, from the north of Haiti who owned a banana plantain plantation right next to, actually, this large U.S.-backed industrial park. He becomes president, continues the corruption, and then is assassinated in 2021. And all of this, all of these things, happen together.

All of these are different explanations about why people are leaving Haiti. You've got natural disasters. Climate change is affecting agriculture. You have neoliberal American agricultural policies which destroy Haitian agricultural tariffs and dump a bunch of heavily subsidized American food onto Haiti. And you have all of this political turmoil, much of which is being done by the U.S., or by the U.S. to Haiti, which explains why so many Haitians are trying to get out, and then because the United States is the place where the money all ended up, they're sort of following the money. They're following the resources here.

Robinson

One of the things that's so aggravating and perverse and evil about the nastiness towards Haitian immigrants is, why are Haitian immigrants in Springfield, Ohio, and not in Haiti? Well, one reason for that is that all sorts of things that we have done for several hundred years have contributed to making it incredibly difficult to survive in Haiti. And you point out in your writing that it’s done in even unintended ways. I think you said that the very fact that so many people were concentrated in the capital city, with the earthquake as devastating as it was, can also be traced back to policy choices.

Katz

Yes. During the U.S. occupation, they made Port-au-Prince a locus of control to a much greater degree than it had been before that. Because if you're trying to run a colonial occupation, it's easier to control a country from a single point instead of having to control the entire thing. Yes, that's absolutely true. The other thing is, we're talking about Springfield, Ohio, specifically, but also the American Rust Belt, and really the United States in general—a lot of these forces that are acting on Haiti are also acting in different ways on the U.S. So, you look at why Springfield needed a bunch of labor. The economy of Springfield, Ohio, throughout the 20th century was industrial, and it was based on two major factories, one of which made magazines, Collier's magazine and other magazines, that went out of business in 1957. So, the major employer up through the early 1980s was International Harvester, the big farm equipment company, and it went belly up in the early '80s largely because of mismanagement, but another way to put it is just corporate greed. The heads of International Harvester were just trying to squeeze their workers, and trying to squeeze their customers, most of whom are farmers and also equipment dealers. The last straw was that they tried to claw back benefits from their workers that the unions had already fought successfully to have, and then this created conditions for a major labor stoppage, which effectively International Harvester doesn't recover from.

And so Springfield is like a symbol of the death of the American dream. And there's an interesting tie in here. As I said before, part of the reason why people fled the Haitian countryside and went to the capital, where they were overcrowded when the earthquake struck in 2010, and why so many people are leaving Haiti now, is because of trade policies which were imposed on Haiti by the United States, by the Reagan, Bush, and then Clinton administrations in particular, which bottomed out rice tariffs and flooded the Haitian market with cheap U.S. government subsidized grain. [...] So you have these neoliberal policies, this corporate greed kind of draining people out of Springfield. It's forcing people out of work in Springfield, and then Springfield thus decline.

Basically, in Springfield in the 2010s, the Chamber of Commerce and the mayor launched a big program to try to bring industrial jobs back to this town in Ohio, but there aren't enough people to take the jobs. I don't know the exact reasons, but for whatever reason, the pay is too low, the prestige is too low—whatever it is, people in southwestern Ohio don't want these jobs, so they need immigrants to do them, or people from other parts of the country. And this happens all over the country. It happens throughout history. It's not a new phenomenon. Somebody hears that there are jobs open. They're good jobs. They pay better than either what they can get in their home country or is available to them, or whatever—housing is affordable, and it seems like a nice climate. And so, a couple of Haitians get hired. They tell their friends, who tell their cousins, who tell their cousins’ friends, and a bunch of people move in.

And this is a boom for Springfield, Ohio. It's reviving what had been a declining population. It keeps new businesses in business. It's creating new jobs around it, because then restaurants and healthcare jobs open, and also Haitians are taking these and are working in the hospitals, and they're caring for people who've already been in Springfield, etc. And what you have to do, if you zoom out to this 30,000-foot level, is to see industrial decline in Springfield and agricultural decline in Haiti. [...] All these things are intimately connected.

So there's a kind of poetic symmetry to Haitians coming and filling these jobs and then helping this town that had been underwater for so many decades. But to understand that, it requires having a larger view, and it requires understanding the pernicious ways in which corporate greed and American policy have negatively affected both people in Springfield, Ohio, and Haiti. You can't have that, so what's the solution? Pit everybody against each other. You guys might have come together and looked at the things that you actually have in common. But, look at these people. They've got a different skin color than you, and they speak a different language than you, and they have different religious practices than you, and they eat your pets. That's the answer.

Robinson

But Trump and Vance are supposed to be the anti-corporate populist Republicans.

Katz

Unfortunately, yes. They keep missing that memo.

Robinson

One might say that the first thing we owe Haiti is perhaps an apology for a couple of hundred years of meddling. It was an interesting thing: Joe Biden's envoy to Haiti, Ambassador Dan Foote, came out a couple of years ago and said what the unspoken U.S. policy has been for 200-plus years. He said,

"I've heard this in hushed tones of the back quarters of the State Department, is what drives our Haiti policy, is this unspoken belief that these dumb Black people can't govern themselves."

That's a direct quote from someone who's a U.S. official. In Gangsters of Capitalism, you have direct outright racist quotes from the period of the occupation when people were using slurs, exactly what Dan Foote is saying here. There are ways in which we have screwed up Haiti and treated its people really, deeply cruelly. Now, obviously it's a kind of counterfactual hypothetical, but you talk about the disaster recovery from the earthquake, and you say in your book that that could have gone differently if it hadn't been done in accordance with this racist philosophy. What could be different, or could have been different?

Katz

Oh, everything. If John Adams won the election of 1800 and recognizes Haitian independence immediately, instead of taking 60 years almost for the U.S. to recognize it effectively as an act of war against the Confederacy—it's only once the Southern senators are out of the Senate that Abraham Lincoln was able to belatedly recognize Haiti. At the very beginning, when Haiti wins its independence in 1804, there are two independent republics in the Western Hemisphere: the United States and Haiti. And they could have allied with each other. They could have helped each other grow. Instead, the U.S. demonized Haiti from the beginning. The U.S. is not really powerful enough at the beginning to have any effect on most other countries in the world, but by the beginning of the 20th century, and then throughout the 20th century, once the United States becomes a world power, it continues carrying those notions and those ways of looking at Haiti as a place to extract resources, as a place to extract cheap labor, and as a people who effectively are, as you say, just inferior—they're too dumb, they're too corrupt, they don't know how to take care of themselves. If things had been different, things would be different—if Haiti had been an equal partner to the United States from the beginning.

And of course, Europe plays an enormous role in this as well, and France especially—I'm not trying to take them off the hook. But there's no reason why coming out of the revolution, Haiti couldn't have been a prosperous, powerful country with ample resources to take care of its own people. There are other examples—Barbados, and Cuba, which has its own long history of U.S. interference and imperialism, but has significantly higher literacy rates and health outcomes and things like this. There are examples in the Caribbean of places that Haiti could have followed the lead of, and then in a world without imperialism entirely, who knows? A lot of the problems that exist in Haiti wouldn't exist, is what I'm trying to say. And just like everything else in life, the best time to have done this would have been 227 years ago, but the second-best time is now—or the 50th best time is now—but to change our policies, to look at Haiti as a partner, as a place worthy of respect and admiration, things could be different.

It's certainly not the only example, but the problem is that Haiti is a classic example of how much easier it is to destroy things than it is to build things. And the problem is that Haiti's government effectively doesn't exist now, again, largely because of foreign intervention. There are plenty of Haitians who bear responsibility for this, most notoriously, the Duvalier dictatorship, which ruled from 1957 to 1986, often with U.S. support—the Duvaliers were a U.S. partner in the Cold War. All this is to say that, not using Haiti as a laboratory for silly ideas, not just trying to exploit Haiti, not just trying to dump problems onto Haiti, not trying to demonize Haiti.

I don't like to essentialize peoples, but as a people, Haitians tend to be extremely, extremely proud of being Haitian, and they love Haiti. And most Haitians that I've met in my life, including ones who now live in the United States, would love nothing better than to live fulfilling, enriching, safe, happy lives in Haiti, in a country that they love. They haven't been really given the chance, and treating them as invaders who are just trying to take our stuff, it just gets it entirely backwards. We're the ones who've been taking their stuff. They want to be happy in their homes. They want to be left alone, but the world has made it impossible.

Transcript edited by Patrick Farnsworth.