How Standard US History Misrepresents The World

Reviewing a standard U.S. educational text on international relations to show how the Chomskyan approach calls into question what seems like common sense.

By this point, readers of Current Affairs will probably have heard me mention The Myth of American Idealism: How U.S. Foreign Policy Endangers The World, the book I’ve co-authored with Noam Chomsky, which was released this month by Penguin Random House. The book attacks the idea that U.S. foreign policy has been benign or benevolent and argues that the quest for global dominance and the maintenance of power are often disguised—by the U.S. as well as other countries—as noble and selfless. Far from being “exceptional” in its commitment to human rights and democracy around the world, the U.S. government has a long, shameful record of pursuing its own perceived “national interests” even when doing so involves egregious violations of international law and basic moral principles. U.S. leaders have frequently couched this brutality in idealistic rhetoric, and the American people are frequently told uplifting fables that bear little relationship to their government’s actual actions abroad. We prove that case by running through a long record of U.S. actions, including our involvement in major wars in Vietnam, Central America, Afghanistan, Iraq, Palestine, and Ukraine. In each case, we argue, U.S. leaders professed a commitment to freedom and democracy, but the actual facts show that the opposite was true: our own actions were eroding the chances for the people of these countries to live freely.

This argument will not surprise committed leftists, who may find that the book tells them only what they have already long since concluded, albeit filling out some factual details here and there. But the book is not an effort to preach to the converted. Rather, it’s written so that readers who have been exposed to little except patriotic mythology can be in possession of the facts that challenge that mythology. I proposed the book to Prof. Chomsky because when I was a teenager, he had been the one to open my eyes to many disturbing facts about how the world really works, and I wanted a new generation of readers to be able to undergo a similarly transformative intellectual experience.

How, precisely, does Prof. Chomsky’s work upend what we might call “conventional wisdom” or the “standard account” of U.S. actions abroad? What are the presumptions and myths that are being called into question, and how can we spot them in the wild? A good way of seeing the value of the Chomskyan critique is to see what it can do when we go through a standard, respected U.S. textbook on international relations. When we do, we’ll see how the facts that Chomsky has amassed can call into question what otherwise looks like plain common sense.

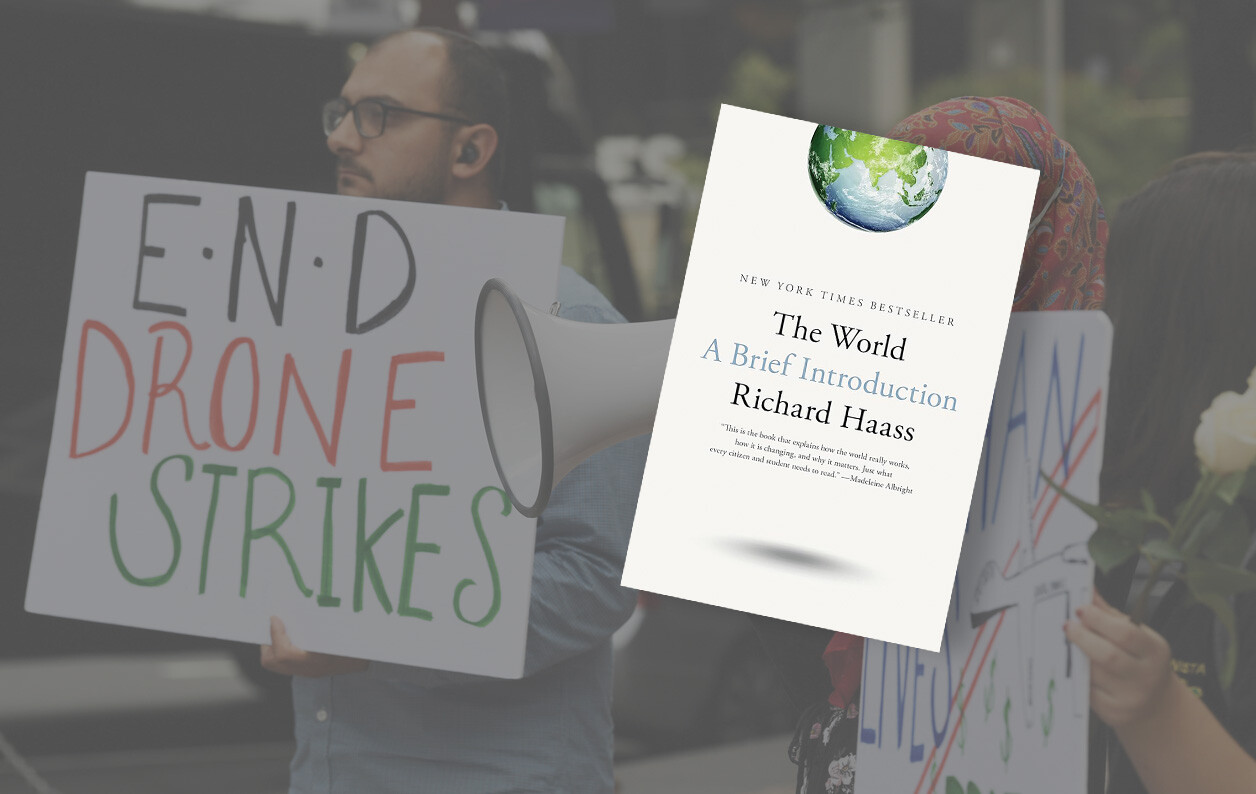

Let’s try this exercise on a typical book by a member of the U.S. foreign policy establishment, The World: An Introduction, by Dr. Richard Haass. Haass is the consummate American diplomat, affiliated with numerous highly prestigious institutions, such as the Brookings Institution, the International Institute for Strategic Studies, the Harvard Kennedy School, the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, and the Council on Foreign Relations, where he served as president for twenty years. He is a moderate Republican who opposed the Iraq War and has advised both Democrats and Republicans. Haass was inspired to write The World after meeting a Stanford computer science undergraduate who knew absolutely nothing about foreign affairs. Haass was troubled, believing that Americans should know something about the world and their country’s role in it, so the book is intended as a primer, one that gives the basic knowledge all Americans should possess. Importantly, this means it’s fair to say that if the book does not include a piece of information, it’s because a typical member of the foreign policy establishment (such as Haass) does not think it’s the sort of thing Americans need to know in order to understand their country or the world.

The World, which comes with effusive blurbs from Fareed Zakaria, Madeleine Albright, and Doris Kearns Goodwin, provides a potted summary of recent global history, guides to each region of the world, and discussions of the most serious issues facing the world today. Everything about it, from its ambitious title to its format reminiscent of the “CIA World Factbook,” suggests neutrality. But it is in the works that most aggressively market themselves as neutral and unbiased that we must most vigilantly look for unspoken ideological assumptions. So how does The World distort the actual world through a pro-American lens?

Let’s take a look at the way Haass describes a few different instances in the history of American foreign relations. Take, for instance, his account of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki:

The United States took the lead in rolling back Japan’s conquests in Asia. By the summer of 1945, most of Asia had been liberated, but Japan had not been defeated. The choice was judged to be either an invasion of the Japanese home islands—something that promised to be extraordinarily difficult and costly—or using a terrible new weapon that would likely convince the Japanese that further resistance was futile. The United States, then led by Harry Truman, who had become president following Roosevelt’s death in April 1945, opted for the latter, and dropped atomic weapons on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Within days Japan surrendered, and the Pacific war (and with it World War II) was over.

This may look like a neutral description. But in this short paragraph, numerous choices have been made about which information is worth including versus which information is to be left out. Of course, the most obvious omission is any mention of the horrific effects that the bombings had on the civilian population. We could tell a story of Hiroshima and Nagasaki that emphasized the extraordinary, historic brutality of these actions and which incorporated testimonies from surviving eyewitnesses to show what it meant for America to become the first (and so far only) country to use nuclear weapons on a population.

Haass might object that he is not intending to bring history alive through presenting the observations of its participants but merely to present the basic facts of U.S. foreign relations in a dry but accessible manner. Now, I would personally argue that you can’t ever really understand an event without understanding what it meant to the people who experienced it, but even on Haass’s own terms, there are a number of crucial distortions and omissions, one that the hypothetical “Stanford computer science undergraduate” won’t notice are being made.

For instance, Haass says that Japan had not been “defeated.” But this is somewhat misleading. Japan had not surrendered, but it had been defeated as a military threat. That’s the reason why a number of leading U.S. military officials later said the atomic bombings had been wholly unnecessary. General Douglas MacArthur, for instance, said he saw “no military justification for the dropping of the bomb.” Dwight Eisenhower thought dropping the bomb was “completely unnecessary,” saying that “the Japanese were ready to surrender and it wasn’t necessary to hit them with that awful thing.” Haass repeats a common argument that the choice was “judged to be” between a full-scale invasion and the dropping of the bombs, and the bombs were thought to be the least-bad alternative. But there is plenty of evidence (laid out by historians like John Dower and Gar Alperovitz) that there were other factors at work in the decision-making, like the low level of value placed on Japanese civilian lives, the desire to make use of a weapon that had been extremely costly to build, and the unwillingness of the U.S. to consider softening its demand for absolute “unconditional” surrender. There are also some deeply ugly facts left out of the standard U.S. narrative, such as the fact that Harry Truman lied to the public and claimed Hiroshima had been a “military base,” that the U.S. covered up evidence of the grotesque harms inflicted by the bombing, and that even after the Japanese had offered to surrender, the U.S. staged a massive additional bombing raid on Japanese cities.

We can see that the omissions change the story. Haass’s account suggests that the United States faced a difficult choice, and there is nothing in the paragraph that should lead us to agonize too much over that choice. The omitted facts suggest that the U.S. may have committed a horrific crime against humanity for no defensible reason. These facts commonly do not appear in textbooks. Personally, I was never taught how widespread opposition to the bombings was among high U.S. officials, and it was only in Chomsky’s writings and talks that I learned that the U.S. kept bombing Japan after the surrender. Chomsky argued consistently that the official history of our country, as told by mainstream intellectuals and the press, systematically suppressed facts that would call into question the basic idea that U.S. motives are noble (even if we make mistakes from time to time). Reading a standard account of the atomic bombings and seeing what it deliberately leaves out confirms that Chomsky is at the very least right to note that we’re not being given the full picture.

As I read through Haass’s The World, my knowledge of Chomsky allowed me to see in many different instances how the facts were carefully being spun to make the U.S. role seem more defensible than it was. Take the Vietnam War. Here is a paragraph in which Haass succinctly summarizes the war’s trajectory:

Following the epic military defeat of France near the village of Dien Bien Phu in 1954, a diplomatic conference was convened to dismantle French Indochina (which became Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam). Vietnam was divided into a Communist north and a non-Communist south, with an election scheduled for 1956 to decide the country’s fate. National elections never took place as the governments of both North and South Vietnam consolidated power and prepared for war. The United States poured in money, arms, advisers, and, when all else failed, millions of troops to shore up a regime in South Vietnam that was challenged by an insurgency supported by North Vietnam and by North Vietnam itself, which was receiving material assistance from both the Soviet Union and China. Successive U.S. presidents hoped not just to preserve South Vietnam but to prevent Communists from taking over all of Southeast Asia. The U.S. effort ultimately failed in South Vietnam, which fell to the North in 1975, and sowed the seeds for the ensuing civil war and genocide in Cambodia.

This is not an atypical “conventional” description. It’s similar to the sort you might find in the curriculum of an Advanced Placement American History class. But once again, crack open a work by Chomsky and you’ll immediately find all sorts of facts that entirely upend the picture presented here. For instance, Chomsky emphasizes, first, the fact that the U.S. was fully supportive of French efforts to retain colonial control over Vietnam (even as the Vietnamese independence movement was pleading with Truman to live up to U.S. values and support their effort to throw off their colonial overlords).

Second, national elections never happened, but not just because the governments of North and South Vietnam were preparing for war, but because the South Vietnamese government refused to hold the elections, a decision the U.S. supported because we knew that the communists would win. As Eisenhower wrote in his memoirs, “I have never talked or corresponded with a person knowledgeable in Indochinese affairs who did not agree that had elections been held as of the time of the fighting, possibly 80 per cent of the population would have voted for the Communist Ho Chi Minh.” In other words, what was presented to the U.S. public as a war to defend a democratic government was in fact a war to keep an undemocratic government in power and to make sure democracy didn’t break out in Vietnam. Chomsky emphasizes that the National Liberation Front insurgency in South Vietnam in fact had massive support among the rural population, but the U.S., under successive administrations, refused to countenance a political settlement that would bring the NLF into government and instead was willing to plunge the whole country into an abyss of death and destruction in a futile attempt to keep an unpopular client state in power. Americans were told they were fighting to stop North Vietnamese aggression against South Vietnam, when in fact we were often fighting South Vietnamese people who were trying to throw off the yoke of the brutal U.S.-backed dictatorship that governed them. The Vietnam War, often presented as having been “begun in good faith by decent people, out of fateful misunderstandings” (in the words of Ken Burns), was in fact a ruthless attempt to keep a friendly authoritarian regime in power at all costs.

Again, the horrors on the ground appear nowhere in the story, such as the extensive use of chemical weapons and napalm. Haass doesn’t even mention the massive U.S. bombing of Laos, which turned the country into the most bombed nation in the history of the world and is still causing the deaths of Laotians thanks to millions of unexploded cluster bombs. How is it that a primer on U.S. foreign policy, intended to educate Americans in the basic facts of what their country has done, could somehow not even mention the biggest bombing campaign in our history? Surely even a cynic has to be a little astonished by how such a significant event could just be written out of history entirely. (Note, however, that every country’s propagandists do this. Britain’s imperial apologists left the history of colonized populations out of school books. Israel doesn’t teach students about the Palestinian “nakba” of 1948.)

Across nearly every major event, The World leaves out critical facts that could, if known, lead the reader to reach more damning conclusions about U.S. conduct. For instance, here is Haass’s recounting of the facts of the Gulf War:

Iraq, then led by the ambitious authoritarian ruler Saddam Hussein, invaded and quickly conquered its smaller and weaker neighbor to the south, Kuwait, making it part of Iraq. It was the sort of naked aggression that Iraq, closely associated with and dependent in many ways on the Soviet Union, would not have been allowed by its former patron to undertake at the height of the Cold War because it could have given the United States the pretext for intervening militarily in the part of the world that hosted the lion’s share of global oil and gas reserves. [… ] [Bush] could not have been clearer in what he declared to an anxious world: “This will not stand, this aggression against Kuwait.” Consistent with the president’s words, the United States intervened, first with diplomacy and economic sanctions, ultimately with military force. President Bush did not want Iraq to dominate the energy-rich Middle East; nor did he want the new era to start with the terrible precedent that force could be used to unilaterally change borders.

Again, we can ask the question: What is left out? Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait was, of course, “naked aggression.” But it was not unprecedented. In fact, Hussein had undertaken a major act of military aggression before by invading Iran soon after taking power. And far from “intervening militarily” when that happened, the United States actually supported Hussein, covering up his use of chemical weapons against Iranians and providing him with logistical support. We supported his aggression when it kept a hostile Iran in check, but we opposed it when Hussein became too big for his britches and it was in our interest to keep him from getting too powerful.

Once again, Chomsky’s writing on the topic adds context left out by writers like Haass. For instance, Haass says the U.S. intervened “first with diplomacy,” implying that Bush used military force as a last resort. In fact, the Bush administration spurned opportunities for diplomacy. As Thomas Friedman wrote in August of 1990, the Bush administration had taken the hardline position that “President Hussein must not only retreat from Kuwait, but he must do so in a manner that leaves no suggestion that Iraq gained from its invasion.” In other words, it was not enough to reach a settlement by which Iraq would withdraw from the territory it occupied. Hussein also needed to be humiliated: “Officials say he must not only be defeated, he must also be seen as defeated by everyone in the Arab world and beyond.” Bush administration officials were worried that diplomacy could succeed and that Hussein could be induced to pull back (thus averting a war). Officials “fear that in the context of a negotiation, the Arab world might be inclined to grant President Hussein some minor face-saving concessions to get him out of Kuwait and remove the threat of a full-scale war in the oilfields of the Persian Gulf.” Note that the administration was particularly worried that Arabs didn’t want a war and would prefer a diplomatic settlement!

As Chomsky documents, Hussein repeatedly made diplomatic overtures suggesting that he was willing to withdraw voluntarily from Kuwait, but the United States spurned these offers in part because war was an opportunity to teach Hussein the lesson that “what we say goes,” as Bush put it. The Gulf War seems less of a heroic attempt to punish aggressors if it becomes clear that the war could have been averted and that the Bush administration preferred war, knowing it could easily win and wouldn’t have to be seen negotiating with Hussein. Haass also notes that in the aftermath of the war, the U.S. declined to offer aid to Iraqis who rose up against Hussein, leading to them being slaughtered. For Haass, this is because we wanted to “avoid getting caught up in taking sides in what was seen as a civil war.” In fact, the uglier truth is that the U.S. may have preferred Hussein remain in charge in Iraq. As Friedman put it at the time, “as soon as Mr. Hussein was forced back into his shell, Washington felt he had become useful again for maintaining the regional balance and preventing Iraq from disintegrating.” For all our supposed principles, the U.S. actually preferred a dictator in Iraq to a popular uprising, so long as that dictator knew his place.

Let us look quickly at two more cases, Afghanistan and Palestine. Here is Haass’s description of the Afghanistan war:

The U.S. administration at the time, that of George W. Bush, demanded the Taliban hand over al-Qaeda members who were operating out of Afghanistan, and when it refused to do so, the United States joined forces with many of the same tribes that had run Afghanistan following the fall of the former king. This coalition succeeded in removing the Taliban from power in 2002. President Bush asked me to coordinate U.S. policy toward the future of Afghanistan from my perch at the State Department. We managed to help the Afghans form a new unity government, but it proved unable to govern the entire country or to end the fighting. […] In the ensuing decade, civil war raged, because the government, supported by forces from the United States and other NATO countries, could not secure the country against Taliban fighters who continued to enjoy great support in the south of Afghanistan (where they had ethnic and tribal ties) and sanctuary in neighboring Pakistan, which opposed the establishment of a government in Kabul with close ties to the United States and India.

Yet again, the moment we pick up a Chomsky book, we see crucial facts left out. Here are just a few: First, the Taliban did indicate it was willing to hand over Osama bin Laden if certain conditions were met (such as the presentation of evidence of his guilt), and the U.S. refused to enter into negotiations over the matter, saying its demand was nonnegotiable. The anti-Taliban forces that the U.S. joined with actually condemned the U.S. bombing of Afghanistan as indiscriminate. Part of the reason the Taliban survived was not just that they “had ethnic and tribal ties,” but that the U.S. was supporting a corrupt and brutal government that did not enjoy popular support, and U.S. atrocities in Afghanistan alienated the population and helped the Taliban recruit. All of this (which we document in the Afghanistan chapter of The Myth of American Idealism) is crucial to understanding the reality of the war, but readers of The World will be left in ignorance.

Haass’s version of the Afghanistan story is similar to others: the U.S. tries to do the right thing, but, sadly, we fail, sometimes through hubris, sometimes because the world is complex and full of people with “ethnic and tribal ties” about which we can do little. But often the reality is that the U.S. was not trying to do the right thing. Instead, successive governments were making callous Machiavellian calculations of what would be best for U.S. power, in almost complete indifference to the fate of the people who would be affected.

For instance, when Haass discusses Israel and Palestine, he says that “multiple diplomatic efforts, mostly led by the United States, as well as one notable undertaking in Oslo in the early 1990s that was spearheaded by Israelis and Palestinians themselves, have failed to produce a comprehensive outcome acceptable to both Palestinians and Israelis.” He says that “Palestinian leaders have shown themselves to be unwilling to accept American and Israeli proposals that offered the Palestinians much even if not all that many wanted.” Haass presents the U.S. as an honest broker that tried in good faith to help resolve a distant conflict but failed simply because the two parties could not agree (and partially because of Palestinian rejectionism). In reality, the U.S. has been a stalwart supporter of Israel, arming and funding Israel as it has systematically dispossessed Palestinians and colonized their land. The U.S. has vetoed U.N. resolutions that would have imposed a two-state settlement on the conflict and has declined to join most of the rest of the world in recognizing a Palestinian state. The central issue in the conflict is that Israel is occupying Palestine and refuses to end its occupation, instead gradually annexing Palestine while refusing to grant Palestinians the basic rights that Israelis have. The U.S. could refuse at any time to continue supporting Israel as it does this. Instead, it offers weapons and diplomatic support, even as U.S. leaders proclaim themselves committed to a “peace process” and a two-state settlement. The U.S. role in the Israel-Palestine conflict has been brazenly hypocritical, and arguably we are the primary obstacle to peace. But in the telling of those like Haass, the U.S. is simply weak and helpless, unable to solve a very complicated situation.

It’s notable that Haass is not a militarist or rigid ideologue. While he has long been a Republican, he is not a neoconservative. Not only was he opposed to the Iraq War, but he argues in The World that NATO expansion was a mistake that unnecessarily antagonized Russia. He has recently been critical of the Biden administration’s outright refusal to consider restraining Israel’s conduct in the West Bank and Gaza. But Haass pushes common myths about the U.S., carefully finessing the historical record to exonerate us of any serious wrongdoing. All the U.S. does is make minor mistakes here and there.

This is the worldview that has been forcefully challenged across Chomsky’s 100-plus books. Chomsky argues that U.S. professions of noble intent ring hollow, that we are a state like any other, without uniquely exalted motives. He encourages us to look in the mirror, to judge ourselves by the standards we judge other countries by, and not to sweep evidence of our worst misdeeds (such as the devastation of Laos, or the atomic bombings, or our shameful role in Palestine) under the rug. Books like The World present an attractive picture, one that Americans may be biased toward accepting, which is that the world is just complicated, and we navigate its complexities as best we can. The reality is that we have inflicted a great deal of devastation on people around the world—without ever reckoning with what we have done or compensating the victims. To those who have been taught The World’s view of the world, I would suggest picking up a book of Chomsky’s like Myth and having a look at the facts you were never told. See how this supplementary information alters your judgment. You may find the experience just as eye-opening as I did myself.