Trumpworld’s Favorite Writer Says The Right Must Emulate Dictators in Battling Leftist 'Unhumans'

Joshua Lisec’s work is highly regarded by J.D. Vance, Donald Trump Jr., and Steve Bannon. He thinks democracy is overrated and that law should be used as a tool of political revenge. He spoke to Current Affairs to explain why his book praises McCarthyism and dictatorships.

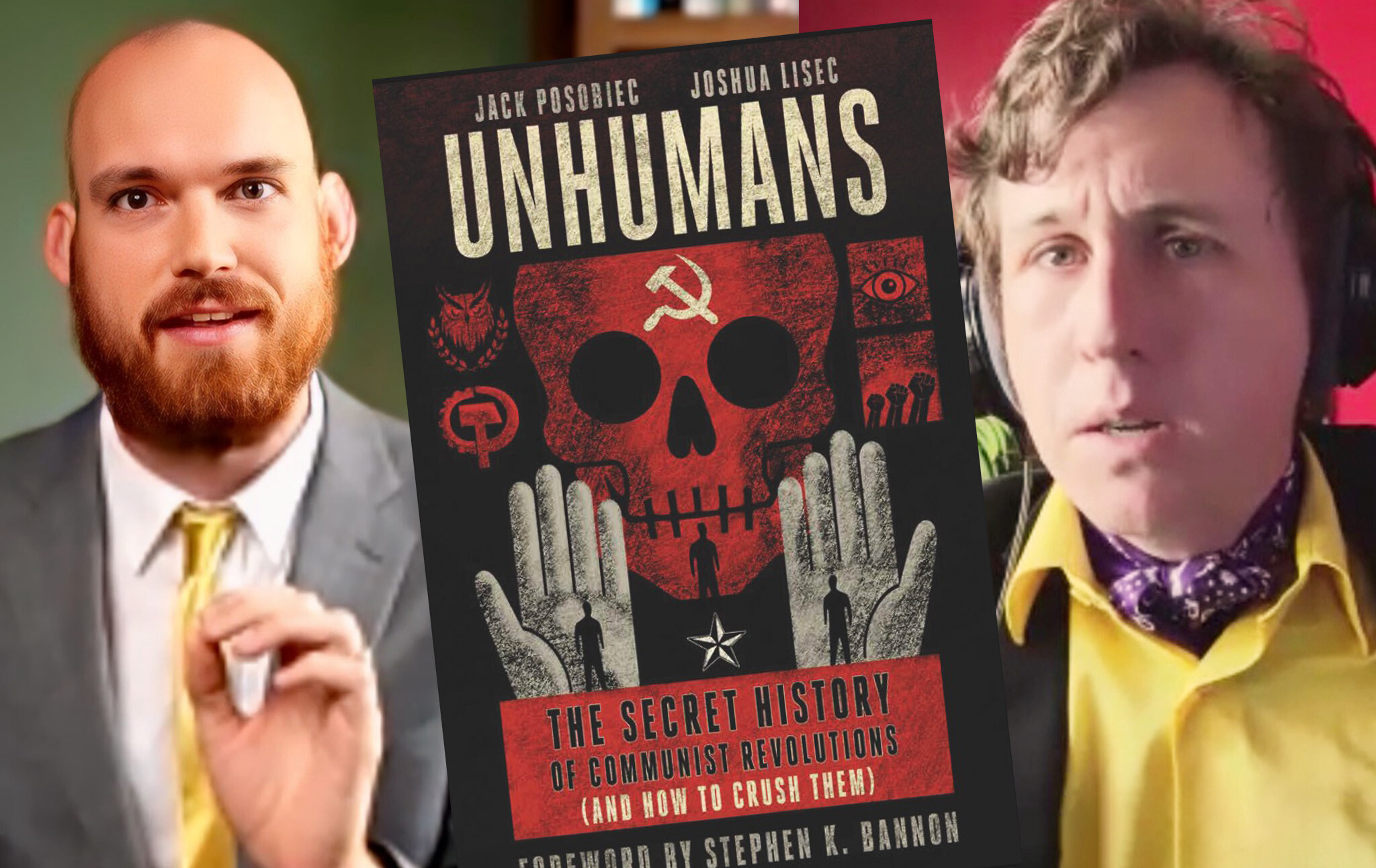

A while back, I became horrified by a book called Unhumans by Jack Posobiec and Joshua Lisec. The book had the endorsement of Vice President-elect J.D. Vance, who wrote a glowing review for the back cover, and is popular among people in Trump’s orbit. Donald Trump Jr., Roger Stone, Tucker Carlson, and Steve Bannon have also boosted the authors’ work. Lisec says that Donald Trump himself has praised the pair’s latest book Bulletproof, which is about the assassination attempt against Trump from this July.

Unhumans disturbed me because it seemed more than a little, well, fascist. It argues that leftist “unhumans” must be ruthlessly dealt with and praises dictators like Francisco Franco and Augusto Pinochet, who were known for inflicting torture, terror, and death on dissidents. It argues that extreme measures, such as the banning of all teachers unions, should be carried out immediately. And it recommends “an eye for an eye” justice: “That which is done by the communist and the regime must be done unto them.” Posobiec and Lisec are not always clear who exactly they think is “unhuman” and what the limits of this ruthlessness should be. They say they are against violence, but they also openly endorse Pinochet’s tactic of conducting extrajudicial executions by throwing people out of helicopters. Lisec also says that certain “actions and ideologies”—note, ideologies—deserve to be met with “capital punishment.” I find it alarming that a book making this case is circulating among people so close to the executive branch.

I received an email from Lisec’s publicist a few months back advertising the book and offering interviews with Lisec, so I decided to take the opportunity to ask him to elaborate on why the book praises Franco and appears to advocate for the abrogation of basic civil liberties in waging an all-out war on the left. You can listen to the full conversation here. My main feeling was that Lisec’s responses were often evasive and did not offer satisfactory explanations of how dictatorial he feels President Trump should be. Nor do I feel he identified who the specific “unhumans” are that need to be fought. I found the conversation ominous, and I do not feel at all reassured that the men who are reading and praising this book, who are now in positions of power, will show a basic tolerance for dissent.

For instance, Lisec reiterated to me that he likes to quote Franco as a stellar example of resolve and will:

Lisec

We like to quote, in English, Francisco Franco's phrase: “Wherever I am, there will be no communism.” And he meant it. It's that resolve, it's that will, that we praise and that we appreciate. Otherwise we become a doormat for evildoers. We say, no, please don't stop. And what are the consequences? There must be consequences.

I followed up and asked for Lisec to clarify what kinds of Francoist methods he believes ought to be emulated here in 2024. The example he gave was jailing political opponents, which he thinks needs to be done:

Robinson

One of the arguments that you make in the book is, you quote Franco saying “we don't believe in government through the voting booth.” And you say “democracy has never worked to protect innocents from unhumans. It's time to stop playing by rules that they won't.” And my understanding of what you're saying is that some of these right-wing dictators like Pinochet, like Franco, were using justifiable methods, and that the contemporary right, which is in its own fight against what you call throughout the book "unhumans," should become more comfortable with these kinds of extreme methods.

Lisec

An example of this would be the idea that we should not jail political opponents. That is a rule that the right has obeyed. For example, after the defeat of Hillary Clinton, remember the phrase, “Lock her up. Lock her up. Lock her up.” Right? It seems as though, from even an objective standpoint, Hillary Clinton was responsible for a number of federal crimes that she received no prosecution for, and Donald Trump explained that for the peace of society and for stability, [he] ought not lock her up, that that was not the right thing to do. Being gracious and being merciful where no grace or mercy were deserved. And then Donald Trump leaves office, and even in the midst of his first term, what happens? He and his people are lawfared into oblivion. We have what, from my perspective, and from a lot of people's perspective, roughly half the voting populace in the country, from their perspective, are political prisoners, where you have someone like Merrick Garland committing the same crime, alleged crime, that Steve Bannon did, that Steve Bannon spent four months in prison for. Meanwhile, Merrick Garland has walked free, and it is that asymmetric application of the law, and we do say that we don't believe anything in anything that's extrajudicial. We simply wonder what would actually happen if we, to the fullest extent of the law under the Constitution, had a willingness to reciprocate.

Thus Lisec’s advice to the Trumpian Right (who are clearly listening) is that, unlike in the first term, Trump should show no mercy and should openly try to put political opponents in jail. What, I asked, about democracy? Here again, Lisec cited the example of Franco and said that it showed that you can’t just let “marauding communists” and socialists do as they please:

Lisec

We found our issue with democracy is that generally it doesn't work, because you get to mob rule, like we saw in Paris and like we saw in in Spain as well, where it was effectively legal for these bands of marauding communists under the socialist rule to go about doing what they wanted, because they were the majority and the majority is mob rule. Fortunately, we don't have democracy in the United States. We have a constitutional republic which is underpinned by representative activities [and] the voting booth, but we have electors. We have a system that prevents mob rule, fortunately, but ultimately, we don't have a situation—at least we haven't—where the right is willing and has been willing to prosecute their enemies to the fullest extent of the law, and it's been that imbalance that has left a lot of good people directly in harm's way.

Lisec was insistent on distinguishing his brand of authoritarian right-wing politics from what he called the “reactionary right,” which he uses to refer to outright racists. (Although his co-author Posobiec has frequently shown no similar inclination to distance his politics from the racist reactionaries.) Lisec gave an example of a “reactionary” as “someone who sees that J.D. Vance is married to a brown woman and has a problem with that.” But I was most concerned not with Lisec’s views on race, but his views on state power. When I pressed him on his and Posobiec’s praise of Franco, he gave a meandering answer that did not particularly reassure me with its invocation of “righteous violence”:

Robinson

Franco seems to be, like, the model here, and he's a dictator who was responsible for mass killings, torture and the systematic and illegal detention of political opponents. The White Terror killed hundreds of thousands of people based on his idea of social cleansing. The country sort of became an immense prison. And so when I see you quoting him repeatedly throughout the book in a positive way, and not really mentioning these things, I certainly get chills down my spine.

Lisec

A couple of things that I think about that, actually three. So one of them is the context of Franco's rise to power was in a civil war. He was a general, and generals in the midst of civil war, in any context, tend to engage in activities that a lot of people outside of a wartime context would call extreme. My middle name is Chamberlain. I'm named after Joshua Chamberlain, the American colonel who led the band that charged on the Round Top during the Battle of Gettysburg. And as a child, I was taken with my family to all of the various American Civil War sites all around the country. And the American Civil War was just something that I knew about, and I grew up with, and there was great heroism, certainly on both sides. But being from Ohio, there's a monument to Union troops. There's the famous Veterans Affairs hospital just down the road from me, and going there every year on Memorial Day, the American side, the Union, is near and dear to my heart from that period, for obvious reasons. And then there's characters like William Tecumseh Sherman. Then there is the, let's say, activities of Abraham Lincoln with the executive branch. And then I grow up, and I believe that I have reached—as I think anyone looking at any period of history needs to have—an adult understanding of the situation, that not everything that someone does makes sense to be repeated or even as an example. And we can look at what someone does that we believe is righteous violence—like I think would be appropriate, say, from the union's perspective. I think [it] would be appropriate to say from Franco's perspective. And it's all right, if the people can disagree with that. People can disagree with that. I'm a Christian, and throughout both the Old and New Testament, righteous violence, war, the sword, has its place in a society. And I know that there's a lot of people that disagree with that, who are 100 percent pro-peace and whatnot. But I think the issue that it comes down to is, we believe—what stops a bad guy with a gun? Some say gun laws. We say, okay, good luck. What stops a bad guy with a gun is a good guy with more guns. And so while Abraham Lincoln, George Washington—and we put Francisco Franco in that same category—is literally everything they did commendable or ideally repeatable? Absolutely not, because I'm not nine years old. And so I think what we have done is we have looked at these examples of history, and we have pulled from what we believe to be their commendable acts, their resolve, their will, and we have praised them and where they did things that we may not necessarily agree with or we do not necessarily see appropriate to repeat we have no reason to say, hey, you should do this too. Because obviously, why would we? But if we were writing a full history of every single one of these periods, perhaps there would be more, right? But this is not a book that's about the Spanish Civil War.

But I wanted specifics: what about Pinochet throwing people out of helicopters? Was that a good thing? Lisec confirmed that, yes, in fact, he believes it was:

Robinson

When you mentioned Pinochet in the book, I mean, you talk about him throwing people out of helicopters, and you say, well, this really upset the globalists. But then your criticism is not of Pinochet, it's of those who tried to prosecute Pinochet and who condemned him for torture and judicial execution.

Lisec

Yes, that is correct. Because the capital punishment methods being what they are from one place to another, the visual of comedy is being thrown out of helicopters. There is a dark comedic aspect to that.

Robinson

I find it revolting.

Lisec

Death is not funny. Obviously, there is a certain aspect to that, let's say, firing squad, is just not. And I will admit that is a turn off to a lot of people. But as I said, we believe that capital punishment does, in fact, have its place, that there are some acts and ideologies that are so hideous they cannot coexist, because they are impossibly coexistent in this place. And the reason we call the book Unhumans is because it's a verb, to unhuman someone. It's not a word that's used much nowadays, and I think its etymology goes back to the 1920s, so it is a verb. To “unhuman” someone means to deprive someone of their rights to life, liberty and property. And communists do that in reverse order. First, they slowly, and then, all at once, take your stuff, then your civil rights, and then the lives of those you love, and then you yourself. It is an anti-human, anti-life death cult we like to to talk about, and there are certainly religious aspects to it. And we can't tolerate an ideology like that, whether it's political communism or it's an equally degenerative ideology like Cultural Marxism, which is sort of a mutated version of the economic version of Marxism.

Well, frankly, I was no less alarmed coming out of the conversation than I was going in. Righteous violence? Capital punishment being used against disfavored “ideologies”? Lisec was cagey about who, precisely, he was talking about and what, precisely, should happen to them. He did say that Bernie Sanders probably shouldn’t be among those thrown out of a helicopter (“I kind of like the old fart,” Lisec told me) and that the unhumans are “those who are prosecuting the innocent” and “attacking good and honest people.” We need heroes, the modern day equivalent of Franco and Joseph McCarthy (“Senator McCarthy was indeed vindicated,” Lisec told me) to stop these people.

Now, you may not have heard of Joshua Lisec and his co-author Jack Posobiec. But some of the most powerful people in the country are appreciators of their work. And I find their views deeply disturbing. I am not excited to find out what it would mean to have them put their ideas into practice, and I think we see here why limits on state power are so crucial to keeping the instinct for persecution, like that demonstrated in Unhumans, in check. Already Donald Trump is repeating the idea that jail is the right place for political enemies, and while we don’t know how far he could take this impulse, we do know where it ends up at its most extreme: in dictatorships like those of Franco and Pinochet.