An unhealthy fixation with financial speculation pervades American culture generally and sports particularly.

Of course, WallStreetBets, the GameStop short squeeze, and a rise in day trading were just some of the manifestations of a broader form of speculation that dominated the early years of the pandemic. This speculation seems to be returning in full force with Trump’s reelection through perhaps the most insufferable means imaginable: cryptocurrency. I won’t spend much time on crypto here, given that Current Affairs Editor-in-Chief Nathan J. Robinson has already written extensively about it in pieces such as, “Why Cryptocurrency is a Giant Fraud.” But what remains important is that cryptocurrency was and still is both remarkably speculative and virtually indistinguishable from betting. As Annie Lowrey wrote in “The Three Pillars of the Bro-Economy,” “Day-trading, sports betting, and crypto are three floors in one bustling, high-stakes casino.”

This kind of high-risk speculation has pervaded hobbies as well. As I wrote in the pages of Current Affairs in 2021, even sports cards have exploded in value on the basis of enormous speculation, with card sales regularly eclipsing millions of dollars and hobby “enthusiasts” spending tens of thousands of dollars to open sealed packs of cards. Having spent a significant amount of time on sports card Instagram and online forums as a collector myself, I’ve observed that the median card hobbyist now seems to subscribe to more or less the same interests as the Barstool Sports fan and crypto enthusiast: Trump memes and sports betting schemes.

Just as Barstool Sports ushered in an era of unfettered sports betting as a certain kind of lifestyle trait, cryptocurrency and r/WallStreetBets gave way to the rise of the toxic “crypto bro,” whose primary affinities include not only crypto but generalized speculative betting, tacky generative AI art, Trump, memes, and sometimes, AI-generated Trump memes. What has come with these affinities is a kind of irony-poisoned politics, one largely of impatience and low impulse control: what matters is that there is something to speculate on, and one’s masculinity is related to the size of the bet.

If Polymarket’s betting market for the election recalled the New York Times’s election needle, or FiveThirtyEight’s simulations, it was not without coincidence. FiveThirtyEight’s creator and election predictor extraordinaire Nate Silver was hired this summer to work for Polymarket itself. Silver has an extensive background in gambling, having supported himself financially for many years by playing poker. A Sports Illustrated profile of Silver noted that “he made $400,000 over three years, and in his spare time began work on his baseball forecasting model” called PECOTA. It was on the basis of this that his career took off. “In 2003 Silver sold PECOTA to Baseball Prospectus for an equity stake, and every year afterward, until he left in ’09,” reported the profile. In other words, Silver made his name in baseball analytics, or sabermetrics—another form of predictive gambling that, as I’ve written about for Jacobin, reflects a certain encroachment of marketized and financialized logic into sports. It was from this vantage point of baseball that Silver turned to politics. Silver himself told the world this in a 2008 op-ed in the New York Post: “I created a Web site called FiveThirtyEight.com (named after the number of votes in the Electoral College) to try and apply the same scientific spirit that we've used in baseball to the political world.” Silver would later candidly tell us, “even my decision to start FiveThirtyEight… was an unexpected consequence of a law passed by Congress that ended my three-year tenure as a professional poker player.”

Silver’s popular books have been obsessed with betting in one way or another—for example, his profile in The Signal and the Noise: Why So Many Predictions Fail—But Some Don’t of NBA bettor and former Dallas Mavericks Director of Quantitative Research Bob Voulgaris. His most recent book, On the Edge: The Art of Risking Everything—which I’ve seen on display at bookstores across Seattle—goes all in on betting. Just consider the table of contents:

- Part 1: Gambling.

- Chapter 1. Optimization

- Chapter 2. Perception

- Chapter 3. Consumption

- Chapter 4. Competition

Two chapters of the book are about poker; Chapter 4 (“Competition”) is about sports betting. “This is also the most hands-on chapter,” says Silver. “I learned the ropes of the industry the hard way, in an experiment where I bet almost $2 million on the NBA in the 2022-23 season.” (It’s hard not to see this as a rationalized form of a gambling addiction.) Much of the second half of the book is about Sam Bankman-Fried, the one-time crypto billionaire and now-felon. On the Edge is so infused with betting that one heading of the Introduction reads: “So, Uh … What If I’m Just Not That into Gambling?” As the New York Times review of the book summarizes: “In ‘On the Edge,’ the election forecaster argues that the gambler’s mind-set has come to define modern life.”

Silver’s hiring by Polymarket is the logical conclusion to a 20-year obsession with statistical analysis and hunting for edge. Even as FiveThirtyEight became a proper journalistic outlet with staff writers, it is clear that Silver’s appetite for betting was being whetted. Of course, Silver’s professionalization of gambling reflects a broader shift among those with an education and background in quantitative methods and STEM. As I mentioned earlier, a surprising number of statistical minds are competing against each other in betting markets to gain edge. Of course, this mirrors a broader professionalization of quantitative trading on Wall Street—a sort of exodus from basic STEM research and applied engineering jobs to quant jobs supporting increasingly sophisticated trading strategies, whether low-latency approaches or machine learning and game-theoretic approaches to beat market competition. Indeed, the worlds of quantitative trading and sports gambling are essentially blurred: the trading firm Susquehanna just opened a sports betting desk, and, anecdotally, many traders take stints playing professional poker or the like in between trading jobs. Trading firms sponsor poker events with prize pools as a way to recruit college students for internships, and some even teach their employees poker as part of their training.

The self-evident point here is that financial markets themselves are uncannily similar to betting markets. They are glorified by writers like Silver and Michael Lewis, whose narratives serve to recruit STEM graduates into the world of financialized gambling just as Barstool Sports pulls college-aged men into sports betting. It comes as no surprise that Silver has relapsed into sports betting just as Lewis slipped into a blind infatuation with crypto in his most recent No. 1 bestseller, Going Infinite: The Rise and Fall of a New Tycoon. It is betting, all the way down. On the one hand, this world is perhaps more measured than Barstool Sports and crypto, in terms of its lifestyle traits. On the other hand, we find that this, too, is enmeshed with politics in a way that ultimately puts profits over people: just as crypto rallied after Trump’s reelection, so too did the financial markets, laying bare an uncomfortable yet important connection between politics and finance.

It is instructive to consider just how fast betting and new modes of speculation more generally have exploded in the United States. As the New York Times reminds us, “Six years ago, sports betting was illegal under federal law.” Limited to Nevada, Delaware, Oregon, and Montana in 2018, sports betting is now legal in 38 states and Washington, D.C. Cryptocurrency exploded in value only a few years ago; regulation has been limited, and what is in place will almost certainly be reversed under the second Trump administration (explaining in part why Bitcoin rose significantly in the weeks after the election). Polymarket is even younger. Though United States residents are forbidden from trading on Polymarket and the Department of Justice is investigating Polymarket for allowing U.S. users to place bets (the CEO’s phone was seized in a recent raid), I doubt Polymarket will wither over the next four years. If we are to do what a sophisticated bettor does—plot the data points and look at the line of best fit—what we extrapolate is that betting is growing at an alarming rate.

While often championed as a form of market and individual freedom, deregulation as a general phenomenon naturally comes at our own expense. We are remarkably bad at making decisions about how we might feel about something in the future. Betting is a prime example of this: it is very difficult for a person placing a first bet with a DraftKings sign-up code to understand how all-consuming and damaging a gambling addiction might be. Gambling, then, is a prime example of a structural problem that’s made worse by deregulation in its various forms, from advertising to making betting on a smartphone easier. Unfortunately, those who are pushing us to gamble the most—DraftKings, Barstool Sports, r/WallStreetBets, crypto influencers, Nate Silver, Polymarket—share one thing in common: they all profit when we bet, and thus, when we lose, again and again.

There are, of course, endless ways to pathologize the proliferation of betting, beyond the regulatory considerations. Marx spoke of alienation under capitalism that decouples one from one's humanity. Sites like Psychology Today lament the rise in “lonely single men” who have presumably too much time on their hands. News outlets regularly cover how goods and services are rapidly becoming unaffordable, which limits options for other activities and forms of leisure. I am less interested in apportioning fractional significance to each of these root causes and am more concerned with what betting as a behavior is bound up with—particular forms of masculinity and cynicism—and how they relate to the present political moment.

In an expansive n+1 piece titled “The Last Last Summer,” the Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist Joshua Cohen recounts his time as a teenager working as a coin cashier at Resorts, a casino in Atlantic City. The essay, written around the 2016 election, is from another time. In it, Cohen reflects on Donald Trump’s role in the decline of the gambling haven. Cohen reports some telling statistics:

In the 1980s and ’90s, the casinos with which Trump was associated comprised between a third and a quarter of AC’s gaming industry…. And then there’s the Trump Taj Mahal, which Trump built with the help of Resorts International in 1990 on financial footings so shaky and negligent that by the end of the decade he’d racked up more than $3.4 billion in debt, including business (mostly high-interest junk-bond) and personal debt which he handled by conflating them.

Cohen makes the case that Trump isn’t just a man hopelessly entrenched in a world of gambling but a politician whose very success is predicated upon the emotionality of placing a bet:

It’s this ambient scare that Trump’s put into the populace, and the way that his ruthlessly calculated vulture-swoops through the news cycle serve to moderate, or exacerbate, this emotionalism, regulating it like a professional thrill, that remind me more than anything of gaming: of what it feels like to put my money on the line. It’s as if Trump—this vanity candidate, famous beyond law—is offering all of us a wager: that he can inflame his rhetoric and press his luck without ever pressing it too far—without alienating all women and black and Hispanic voters, and without getting too many Mexicans, or too many Muslims, or even just some white Democrats, beaten up or killed.

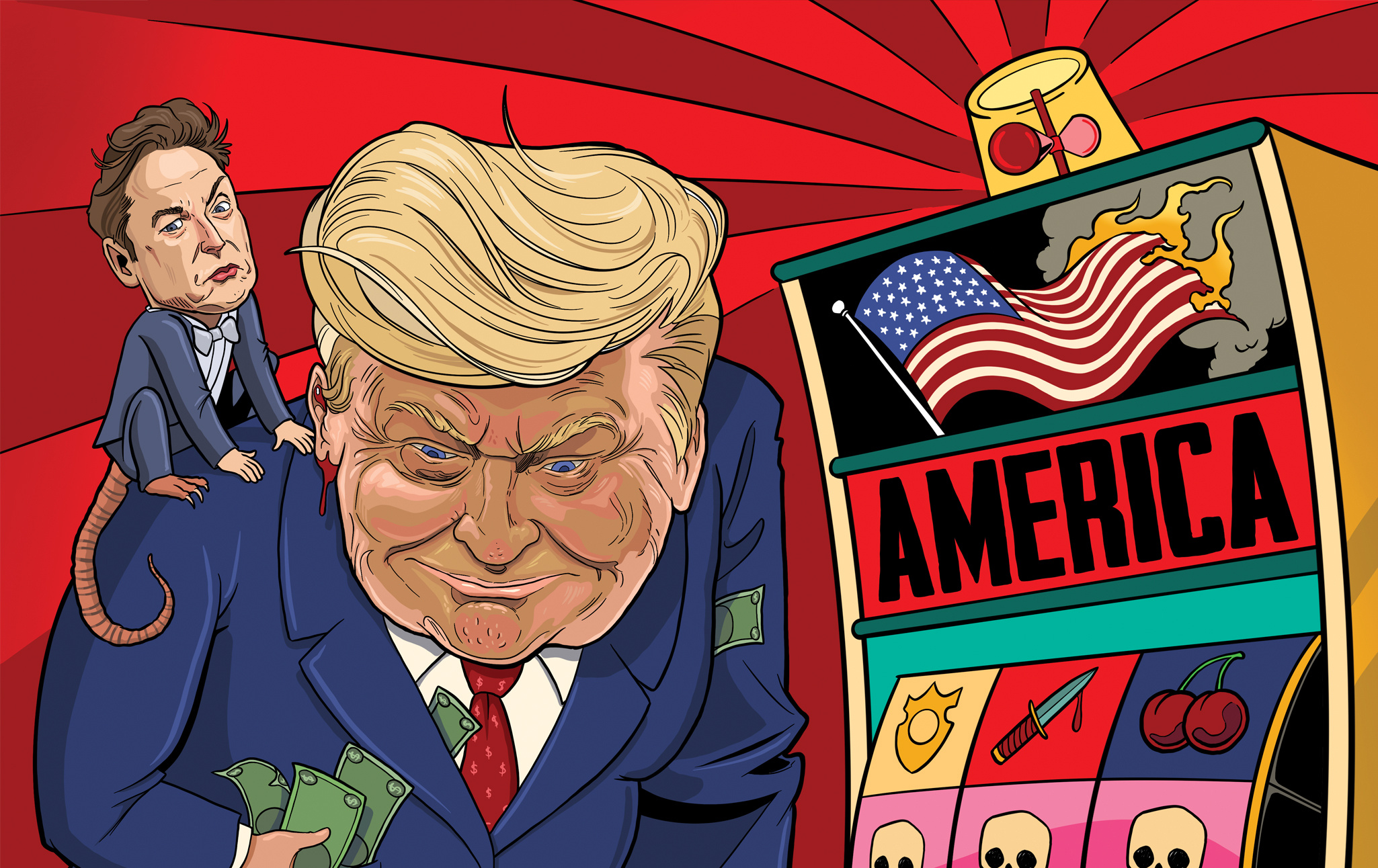

At this point, enough ink has been spilled on Donald Trump the man and the criminal. What matters to me is the idea that beneath it all, Trump and MAGA are intimately connected with gambling—not just in an explicitly financial sense but in this deeper way that Cohen aptly picked up on almost a decade ago and which is amplified and rendered even more explicit with each new encroachment of betting into our daily lives. There’s probably not much sense in Monday morning quarterbacking the election at this point, but I find the Barstool Sports-ification of younger men, the erosion of their impulses via the thrills of cryptocurrency and r/WallStreetBets, and the growing seduction of Polymarket-like betting to reflect a deep-seated relationship between financial aggressiveness and, as hackneyed as it sounds, a profoundly toxic form of masculinity—one that Wall Street is both famous for and laid the precedent for. Fifty-six percent of men aged 18-29 voted for Trump in this election, up from 41 percent in 2020. This is, as USA Today proclaimed as part of a recent headline, reflective of the fact that “Gen Z Bros Love MAGA.” I imagine too many of them followed the election by monitoring Polymarket, not for the political implications of the real-time probability updates but rather for the bet itself—their votes cast as a perverted sort of skin in the game that gave way to surges of dopamine as the market resolved to Trump.

In his n+1 piece, Cohen goes on to conclude the section on Trump and gambling with the observation that:

Ironically enough, most of the more reliable sites that’ll trade US election action for cash are registered in the UK, the Bahamas, or elsewhere abroad, because America doesn’t quite approve of betting on politics – not because betting on politics is cynical, but because it’s considered a variety of sports betting, which is illegal in all but four of the states. America: a country in which even a noble law has to be justified through the drudgery of precedent and stupid technicality.

Here we are, eight years later, at a time in which this law on sports betting has long since been overturned by the Supreme Court, and betting on anything, even as an American citizen, seems more and more of a possibility within the next four years. Of course, this was always possible in financial markets through various market positions—but now, the bets might be made explicit. Perhaps the addendum to Cohen’s proclamation should read:

Illustration by

Illustration by