The Taking of Children

Sociology and law professor Dorothy Roberts exposes how the child protective system systematically targets poor Black families and argues that abolition of the system is necessary to stop this injustice.

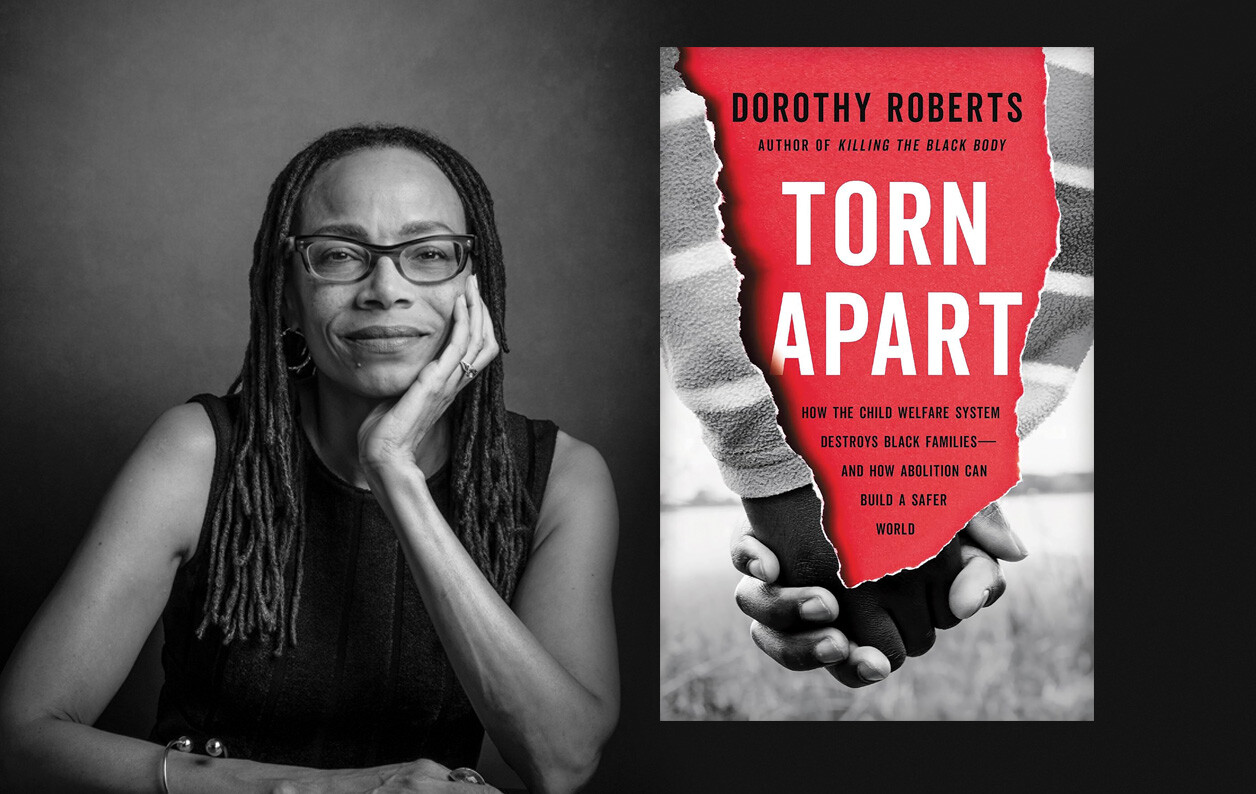

Is our “child welfare” system successfully helping protect kids from neglect and abuse? Or is it inflicting widespread trauma through unnecessary, unjustifiable family separation? Dorothy Roberts, professor of law and sociology at the University of Pennsylvania, has long been one of the country’s most deeply-informed and coruscating critics of “child protective services,” which she argues systematically targets poor Black mothers whose only parenting error is to be poor. Roberts is the author of Torn Apart: How the Child Welfare System Destroys Black Families—and How Abolition Can Build a Safer World, which sums up over 25 years of her research into the subject. Roberts is also a 2024 winner of the MacArthur fellowship, commonly known as the Genius Grant.

nathan j. robinson

You're doing something very difficult in this book. You are upending people's understanding of the seemingly obvious. You talk about how we use words that are ultimately perverse euphemisms: “Child Protective Services” and even “child welfare.” It's a tough task because you're talking about something that many people won't even have thought about. They will assume there's a system out there that deals with cases of abuse, and you're saying, “It is not at all how you think it is.” How do you begin to unsettle people's presuppositions?

Dorothy E. Roberts

You're absolutely right. I think it's even harder to get people to understand how punitive the child welfare system is than for them to understand how the criminal legal system or prisons are oppressive. People expect prisons to be punitive, whereas there's a myth deeply embedded in our culture and our politics that the child welfare system—and as you point out, it's partly just the words that are used—improves children's welfare, foster care takes care of children, and child protection protects children also, even though this system separates hundreds of thousands of families, with hundreds of thousands of children in the foster system that have been forcibly taken from their families.

Most families, especially white, middle-class, and wealthy families, have no idea what the system does. They've never encountered it, and so all they know is what they see on TV or read in the paper or on social media, which for a long time has been very biased against families that are involved in the system and very pro-family separation. So, it's a difficult task. What do I do to get people to see? One is statistics.

robinson

Yes, they're shocking. They really are.

roberts

People are shocked when they find out that 200,000 children, at least, are taken from their homes every year, that there are millions of child welfare investigations every year, and that all it takes is an anonymous phone call to a child abuse hotline to trigger an investigation. And one of the most shocking statistics to me is a recent study that found that half of Black children in America—more than half, 53 percent—will experience a child welfare investigation before they reach age 18. So, just the numbers alone, I think, are very shocking. The United States separates more children from their family than any Western nation. So that's one.

The other is to tell the stories of families that have been terrorized and torn apart by the system. People are surprised when they hear that there are children who've been forcibly taken from their homes because a caseworker thought their house was too messy or they found some marijuana in the home, even in a state or city where it's legal to possess marijuana in your home. Most children who are in foster care are there because of so-called neglect, and neglect is almost always associated with poverty. Simply look at the definitions and state statutes. It just means that the family has failed to provide some material need. It could be clothing, education, healthcare, or housing. People are surprised when they hear the stories.

I point out the history of this system, which was never developed to be a system to really support families and keep children safe. It was, from the very beginning, developed as a way to deal with impoverished children's needs without having to actually provide for their needs. It has always targeted impoverished families, and for Black and Indigenous families, it has been used deliberately—explicitly with Indigenous families—as a weapon of war, as a way of destroying communities.

Robinson

You've begun to discuss something that's an incredibly cruel feature of the system. It’s hard enough to raise a child when you are poor, when it's a struggle to provide and you just don't have much money. You are talking about the symptoms of poverty: the fact that because you're working all the time, your house is a mess because you don't have time to take care of it, and you can't pay for a cleaner; the fact that there's not much food in the fridge because you can only buy food for the next couple of days. These things are not just your day-to-day struggle, but they are then used as evidence against you, as evidence of your own failures, and they can be used to justify the worst and most horrendous conceivable outcome, which is the removal of your children.

Roberts

That's exactly right. It's one of the cruelest things about this system, what I call a family policing system, because that's really what it does. It targets the most marginalized and vulnerable families in our nation, and it punishes them for being the victims of social inequities. So instead of seeing a family that has [material needs]—insecure housing, roaches and rodents in their apartment, not enough food or clothing, they’re unable to afford healthcare, they have a child who's struggling with a mental health disorder, and they can't afford proper care for that child—and offering to provide these material resources, the response of the system is to punish the parents who are struggling with inadequate means to be able to care for their children.

As you said, [child removal] is for most families the worst nightmare that could ever happen to them. Their children are taken from them by force and put into a system, and they don't know what's happening with their children other than knowing that their children are traumatized by this. Also, it’s well-documented that the foster system in America has terrible outcomes for children. So it's just one violence after another after another for these families.

Robinson

One of the things that you draw attention to that’s under-discussed is the fact that—well, obviously, there are serious cases of child abuse out there, and you discuss those in the book. But then the separation of children from parents is also, in itself, a form of child abuse. You look at the effects, and you quote pediatric experts who say that this is a catastrophe for both the parents' well-being and for the child's well-being. And we know this because of the Trump family separations. Even when the children were put back with the parents, the children were incredibly traumatized by it.

Roberts

That's right. So, first of all, anyone who has a family—we all do, whether you're a child or a parent—knows how devastating it is even to lose a child for an hour, let alone to have your child taken from you, and it's well-documented by pediatric experts that family separation is one of the worst things you can do to a child.

So, as you mentioned, during the Trump administration, when there was an increase in family separation at the border, there was an outcry in our nation because people recognized that an extremely harmful and cruel thing to do to a child is to take them away from their parents. There were briefs filed in federal court, there were briefs filed at the U.N., about how this family separation constitutes even a form of torture for children and their parents. So we know that this is harmful.

But many Americans have been convinced that it is better to put children through the trauma of family separation than to leave them at home. They don't realize that the vast majority of children who are removed from their homes aren't removed because of physical or sexual violence or abuse. They're mostly removed because of neglect. And so you have loving, caring parents who, in most of these cases, are trying to take care of their children, and they just don't have the material resources. And instead of helping them, you're making it worse for these children by adding this trauma to their lives.

Robinson

You mention this idea of neglect. We recently did a program on “broken windows” policing, which emphasized the need for the police to enforce something called “order.” And in that program, we discussed how people's conceptions of “order” and “disorder” are racialized. That is, what they perceive to be a disorderly neighborhood coincides and maps on very well to the race of the neighborhood. You've discussed poverty so far, how the symptoms of poverty are treated as neglect. But also, a very strong theme that you emphasize is that these perceptions of neglect are also racialized.

Roberts

Absolutely. One of the reasons this kind of government terror in families is justified or excused is because of this myth that children will be better off anywhere else but with their families. Now, that myth is supported by long-standing stereotypes about Black families, that Black children grow up in disorderly homes where their parents don't really care for them. These are ideas that stem from the institution of slavery and the separation of families during slavery, and the myth that Black children and their parents weren't really harmed by this separation because they didn't have strong bonds with each other. And I think this is one of the most profound—in a negative way—and influential ideas that fuels the child welfare system, the idea that Black children, even though they may be harmed in foster care, are still better off taken away from their families than being raised by their Black parents and family caregivers. This racial bias in child welfare decision-making is so well-documented.

I'll just give you a few examples. We know very well from multiple studies that doctors are more likely to interpret injuries to children as child abuse if the children are Black. There are studies that look at the X-rays and compare the doctor's response to a toddler with a fractured bone that looks exactly the same in a white toddler and a Black toddler, but it's far more likely that the doctor is going to suspect and test for and report child abuse in the case of Black toddlers than white toddlers.

Multiple studies show that in the case of suspicion of drug use during pregnancy, doctors are far more likely to suspect that Black women are using drugs while pregnant than white women as well as test for it and report it to child welfare agencies. And then there was a study in Minnesota that used a test that went out to all social workers who were trying to be licensed in the state, and they showed them pictures of a so-called messy house, which I mentioned can be grounds for removing children. And they showed them the same picture of a messy bedroom, one that had a Black child on the bed and another that had a white child on the bed. A significant number of these social workers who were taking this test felt that the picture with the Black child showed [neglect in the] house compared to the picture with the white child. [There is plenty of] documentation of racial bias, which is also borne out in the statistics that show that Black children are at least twice as likely to be removed. And also, it's more likely that Black children will be removed for the same kinds of risks to children than white children. There's so much evidence that it's related to racist ideas, biases, and stereotypes about families.

Robinson

Now, despite that evidence, you do point out in the book that one of the things that some supposed experts on this system have done is to try to produce refutations of this that show that there's no bias when you account for certain things. But you point out that the way this is usually done disguises the bias. Can you tell us a little bit about how it's easy to manipulate perceptions of the system to make it seem less unjust than it is?

Roberts

I call these researchers “disparity defenders” because it's indisputable that there's a huge racial disparity at every point of child welfare decision-making. So they have to come up with a justification and also sound benevolent because they're supposed to be caring for children. So overall, what they're saying is, Black children need these so-called services more than white children, that this is actually beneficial.

Well, one problem is, what are these services? They're surveillance, monitoring, and regulation: a forced task that families have to comply with to get their children back or keep their children. It's very strange to call these “services” when the people who are being forced to undergo them don't want them. They know what they need for their families, and that's not what this system is giving them.

So first of all, just the whole approach is disingenuous. It’s a cruel approach. It's a disrespectful and devaluing approach. But many of them are trained statisticians—quantitative researchers—and they are able to manipulate the statistics by controlling for multiple factors. So if you control for poverty, a single parent, households, and neighborhood—all these factors that are associated with race—you can eliminate race as a factor and make it seem as if race has nothing to do with it.

There’s also conflicting statistics and studies. When I started doing this research over 20 years ago and reading the articles, I was just surprised that it was so controversial. You could find studies that found race was a significant factor and studies that found that it wasn't a significant factor. And so people who are experts in statistics can tell you that you can design a study in a way that can erase a significant factor through all sorts of controls and different kinds of manipulations.

Robinson

Because the [agency] reports themselves are influenced by the bias, it's actually very difficult to say which are real cases. If you want to come to a very clear conclusion that says that, “actually, these separations are the result of real cases of abuse and neglect,” what are you going to do to determine the “real” cases when the evidence you have is contaminated by the bias of the perceptions? The same is true in policing, where people who say that there's no racial bias in policing often rely on the police’s own accounts of situations.

Roberts

Absolutely. It's hard to prove empirically one way or the other in a particular case whether it resulted from racial bias or not. Actually, some studies have found actual racially biased statements in the records. So sometimes caseworkers or other reporters will make racist statements. One study in Michigan found that Black families were often described as “drug using” even when there was no evidence they used drugs—it was an assumption they were using drugs.

So for me, it's not so much relying on these studies that try to show whether race is a significant factor or not, it's that we know absolutely that Black families are targeted by this system because of the very high rates of investigations. When you take the fact that most Black children will be subject to a child welfare investigation before they reach age 18, that is significant in questioning the relationship between the system and Black people. When you go to most big cities—I haven't studied all of them, but I think saying this is very sound—and you look at the neighborhoods in which child welfare investigations are concentrated, you will find that they're concentrated in impoverished, segregated Black neighborhoods. So that means something about the relationship between this form of state intervention and Black communities.

And then you have to ask, is this helping these communities or not? When I started looking at this in Chicago and sat in family court, and all I saw were Black mothers pleading to get their children back, it was so obvious this was a system targeting Black families. Now, were these mothers helped? Did they feel that they were getting help? For me, right away I thought, if you've got a system of government in the United States that is targeting people who don't want it, and they are disproportionately Black, the first presumption should be that this is harmful. Joyce McMillan in New York City says, if this were such a good system, we would need affirmative action to get Black people in it.

Robinson

Right, because it’s a “Child Welfare Service,” and we help your children's welfare. People would want that.

Roberts

Exactly. Black people would be lined up. But they're fearful of this system.

Robinson

You've talked about the trauma of actual separation, which is so severe. But also, just the fact of an investigation to begin with sets up a presumption of guilt, where you have to prove that you're a good parent. As I was reading your book, I couldn't help but think that at no point in my childhood did my mother have to prove to anyone, ever, that she was a capable parent. There was no moment where someone asked for evidence of that. Whereas in the system that you're describing, even in the majority of cases where the investigation is closed, and they say, “we've decided that you are fit,” there's a level of proof now that the majority of Black parents have to have. They have to undergo a test that white parents do not have to undergo.

Roberts

Let me put it this way to be perfectly accurate: it's the parents of a majority of Black children—because these families will have more than one child—who have to undergo this. And think about it: what triggers [this process in which] you have to prove you're a fit parent? It is mostly calls to a child abuse hotline, which can be completely anonymous. And so it can be from a biased doctor, a biased teacher, a biased social worker, or a doctor, teacher, or social worker who wants to help the family and doesn't realize that this is going to lead to a traumatizing investigation and perhaps family separation. This system relies on mandated reporters instead of giving resources to these professionals who are supposed to be helping you care for your children. And so, based on a tip or a report, which can be completely false, an investigation begins.

As you said, most investigations are unsubstantiated—the accusations are unsubstantiated. But still, think about what this investigation is. You're terrified. They tell you that if you don't prove you're a fit parent when they knock on your door, that if you don't let them in—which, by the way, violates the Fourth Amendment, under which you have a right to be presented a warrant before a government agent comes in to search your home, but this is rarely applied—[they're going to take your children]. But once you let them in—because you're terrified that if you don't, they're going to take your children—they can search every corner of your house. They can wake up your children and drag them out of bed and strip-search them to look for evidence of abuse even when that's not the allegation.

Let's say they don't find evidence of the harm that was alleged. They're going to keep looking for evidence of something else, and so they get private, confidential records from schools, from hospitals, from other sources. They hire big companies like IBM, SAS, Deloitte, and others to conduct these predictive analytics based on huge databases of private information about families. Then they have this army of so-called mandated reporters who can provide more evidence to try to get families who are accused to be prosecuted. It's very much like a criminal case prosecuted against parents if they don't prove they're fit.

You pointed out that your parents never had to prove that, and it is an important point: most white parents never have to prove [fitness to parent]. But many more proportionally Black parents—a larger percentage of Black parents—have to prove to child welfare workers that they're fit parents, and wealthy white people rarely ever have to prove it, even when their doctors may have evidence that their children have been neglected or abused, even when the children might be suicidal or suffer from anorexia or other kinds of harms that they may blame their parents for.

If you read almost any memoir by a wealthy white person—maybe it's just the ones I read, I don't know—every one I've read recently tells a story of parents who psychologically or physically abuse them. There's one that was just in the New York Times yesterday, and I saw a program on it on the CBS “Sunday Morning” show—not to single her out—by Ina Garten, the “Barefoot Contessa” chef who has a new memoir out now. She talks about her traumatic childhood, of the father who beat her, who dragged her by the hair. He was a physician, I believe. I have never seen in these bestsellers in the New York Times—

Robinson

Child Protective Services (CPS) never shows up in those books?

Roberts

Never shows up. And this television actor who wrote I'm Glad My Mom Died, everyone on the set knew her mother was psychologically torturing her, and nobody thought to call CPS on her.

Robinson

Because it's understood that it’s not for wealthy people.

Roberts

It's understood. Now, I'm not arguing that we should expand and take their children away, too.

Robinson

“CPS for all.”

Roberts

That's never going to happen. Because if white children, especially white middle-class and wealthy children, were taken from their homes at the rate of Black children, it would be—

Robinson

A national scandal.

Roberts

It's never going to happen because it's not designed for them. It's designed for marginalized communities.

Robinson

And “neglect” doesn't mean neglect because, as you say, rich parents neglect their kids all the time.

Roberts

Exactly. It doesn't mean the same thing because wealthy parents have the money to pay for the clothing, the housing, the education, and the medical care. All I'm arguing is that it's unjust that you let wealthy parents rely on their means to take care of their children, but then you target for trauma, terror, and harm—family separation—the families who don't have those means. What we should do is provide for all families the means to take care of their children.

Robinson

One of the most disturbing things that you discuss in the book is the financial aspect. One of the darkest parts of this country’s history, the fact that for many years, during the period of chattel slavery, Black children were actually taken from their parents and sold. But the fact is that even today, there are plenty of people who do well because of this system, who benefit and profit from it, which in some ways does make it a system in which children are still taken for money. So, could you tell us about the kind of perverse financial incentives that are built into parts of the system?

Roberts

Yes. Money makes a difference. Why does this system continue, despite all its flaws and failures and harms? It is an investment for many people, and also, it supports a capitalist approach, that you have to rely on market-based, private means to be able to take care of your children, and if you can't do it, you get thrown in jail, or you have your children taken. That is the basic capitalist approach to care in this nation, and part of that approach is for people to make money off of the removal of children. Multiple agencies—private nonprofit as well as for-profit agencies, along with public agencies—make money every day that a child is kept in foster care. They are paid to maintain children away from their home. Most of the money that is in this system, which is tens of billions of dollars, goes to maintaining children away from their homes. Ten times as much money is spent on maintaining children away from their homes. So these companies are profiting, making money from keeping children away from their families. That's one part of it.

Another part of it is how the government steals the benefits of children who are entitled to Social Security benefits because their parent is deceased or because they have a disability. And in jurisdictions around the country, the state becomes the guardian because it's the guardian of these children. It takes control of their benefits, and it does not save it for them. It does not spend these benefits on them. It spends it on whatever they want to spend it on. So sometimes children age out of foster care at 18 or 21, and they have no money even though they are entitled to thousands and thousands of dollars in Social Security benefits.

And then there are some departments that charge families for the costs of forcibly taking their children away and keeping them in the foster system. So in multiple ways, this is a system that continues because it's financially beneficial to many people who are hired by the system to keep children away from their families.

Robinson

Now, we don't have time today to go into all of your prescriptions for an alternative, which is a long project that requires dismantling this system piece by piece and putting real care in place. Obviously, step one is to understand the kind of system we're dealing with, the horror that is inflicted every day around this country, and to start thinking and realizing how deeply wrong this thing that is accepted as benevolent and normal is, and the adversarial approach, this presumption that mothers are under suspicion and not instead that they probably love their children and need help—that presumption needs to shift. How should we begin to start thinking about the alternative?

Roberts

It’s an abolitionist frame of mind, and that means both dismantling this harmful system we have now, piece by piece, through legislation, for example, and actually applying the Fourth Amendment to parents and forcing these state agents to get a warrant before they search someone's home, providing lawyers for families—whatever can reduce the power of the system. But at the very same time—this is equally important—reimagining what it would mean to actually support families and keep children safe. That means community-based resources.

One way of thinking about it is to take the billions and billions of dollars that are spent on separating families and keeping children in a harmful foster system and give that money directly to families. We have so much evidence now that giving cash to needy families improves children's welfare. We should have known that, anyway, but we learned from the COVID policies that it helps children. Unfortunately, Congress ended those, and we saw the child poverty rate double since then.

One easy way of thinking about it is to think about how we can shift the resources and the attention from punishing and separating families to community-based resources and policies that actually support families and help them take care of their children.

Robinson

And I want to emphasize that you're not talking about ignoring genuine cases of child abuse. I'm sure that's the first reaction that you always get. People say, here's an instance where a parent killed their children.

Roberts

Right. I'm not ignoring that at all. What I'm saying is, if we had an approach that generously helped struggling families, it would drastically reduce what are rare cases of extreme child abuse and killing of children, and we should also be looking into other ways of approaching the reasons why there's domestic violence in families, whether it's against an intimate partner or against children, and often those are tied together. [The current system] doesn't get at the root of why there's so much violence. And in fact, it deters survivors of domestic violence from getting help because they're afraid their children are going to be taken from them. So we need to just radically change the way we approach this. When you read about a child who was killed at home, it seems like almost always it's a child known to the system, and the system failed to protect that child. So why are we putting more money and more attention into a system that has failed to protect children, instead of imagining and building radically different ways of truly protecting children and keeping them safe?

Transcript edited by Patrick Farnsworth.