The Super Bowl Exposed the Brutality of America’s Class Divide

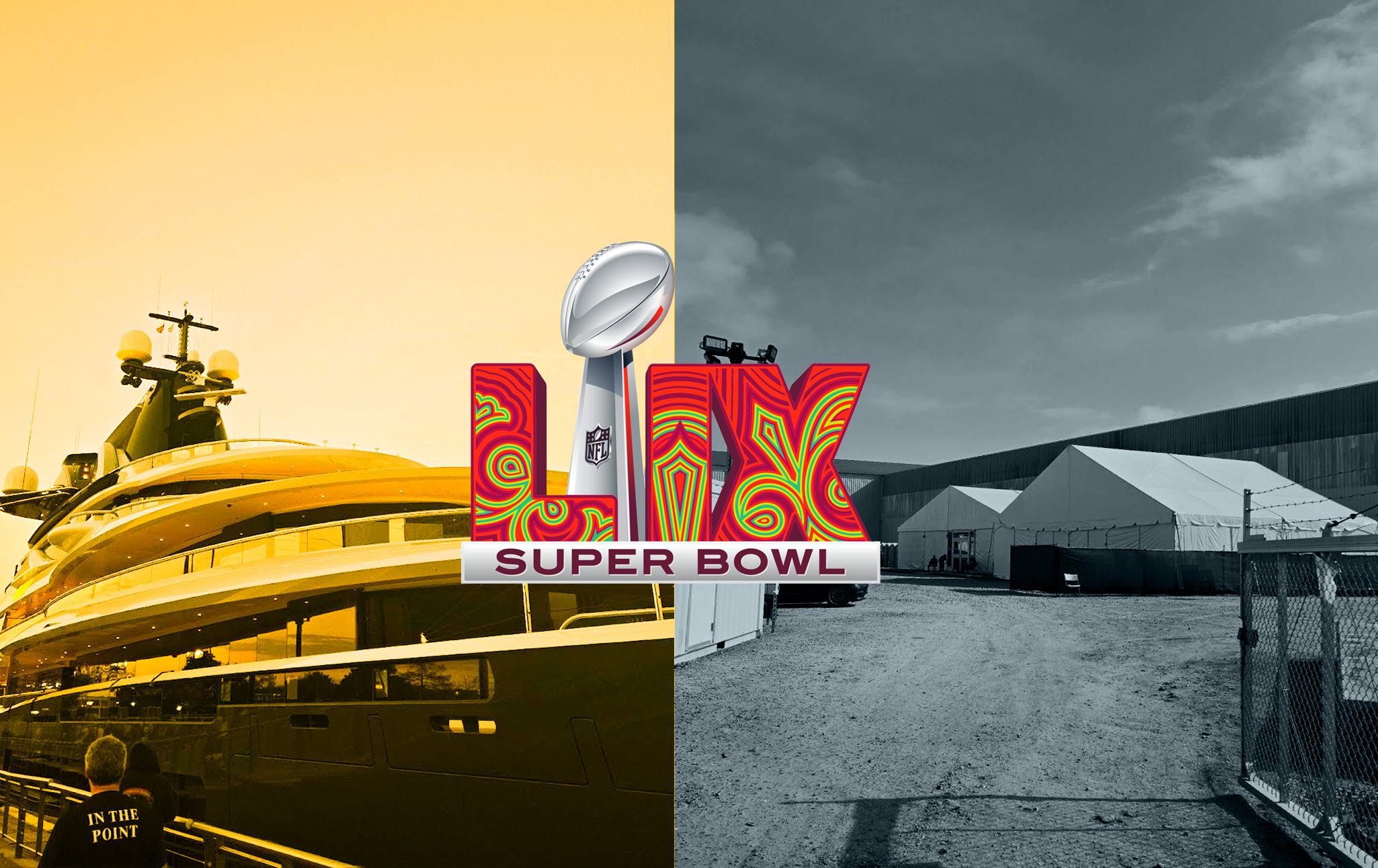

For the Super Bowl, New Orleans forced unhoused people into a grim warehouse—and paid a private contractor $17.5 million for it—while billionaires’ superyachts floated on the Mississippi. How much longer will we tolerate this obscene inequality?

When the Super Bowl comes to your city, everything changes. Now in its 59th incarnation, the event is less a football game and more a mini-industry all its own—a great shrieking engine of commerce that happens to have a football game attached to it. Here in New Orleans, around 100,000 tourists came to town for the occasion, and the NFL raked in at least $66.5 million off stadium tickets alone. The average seat at the game cost around $4,708, and that’s not counting the airfare to get here, so to attend at all, you had to be pretty well-off. For about a week, the Super Bowl affected people living and working in every industry, from construction and transportation to retail, food service, hotels, casinos, and more. There was no avoiding it. For some people, it was an opportunity to make a lot of money, or to flaunt the wealth they’ve already got. For others, it was a bitter reminder of how little they have, and how little anyone in power cares about them as a result. Huge luxury yachts floated on the Mississippi, an army of cops conducted violent “sweeps” of the city’s poor and unhoused citizens, and private contractors got millions of dollars to cram them into a drafty warehouse so the tourists wouldn’t see. The whole thing was loud, gaudy, unapologetically excessive, and pointlessly cruel—a perfect snapshot of the brutal inequality that defines life under American capitalism in the year 2025.

The Yacht

Photo: Alex Skopic for Current Affairs

You can’t fully understand what a luxury superyacht is all about until you see one in person, and I don’t mean it as a compliment. When you first walk into view of the boat, parked by the walkway along the Mississippi River, its sheer bigness distorts your sense of perspective. You know how big a boat is supposed to be, but this one is several times that size, which makes all the people and structures around it look tiny by comparison, like an optical illusion. Its hull is a smooth black wall, and through the windows you can just barely snatch glimpses of opulence: cut-glass chandeliers, glittering staircases stretching from one deck to the next, U-shaped sofas with crisp white slipcases, the vibrant blue of an onboard swimming pool. And then, inevitably, you think to yourself: hang on, one person owns all this?

The yacht is called the Kismet, and it belongs to a man named Shahid Khan, who also owns the Jacksonville Jaguars. Like every owner of an NFL team—and incidentally, isn’t it creepy to talk about “owning” a group of human beings?—Khan is far too wealthy for his own good or anyone else’s, with an estimated net worth of $13.4 billion. He got that way by running a company called Flex-N-Gate that makes car parts (especially bumpers) for the Big Three automakers in Detroit. Predictably enough, he’s also spent decades exploiting and harming the workers who actually make all his products. In 2012 Flex-N-Gate got hit with a $57,000 fine from OSHA for “serious” health and safety violations, including cases where workers were exposed to chromic acid and chromium dust particles—which can cause lung and nasal cancers—without the proper training, safety gear, or medical examinations. (Of course, for someone like Khan, $57,000 is a negligible amount, like losing a nickel in the couch cushions. It’s doubtful he even noticed the fine.) The company also has a history of deploying union-busting tactics, like deliberately hiring workers who speak several different languages so they can’t communicate with each other or United Auto Workers organizers, or strategically scheduling workers for certain shifts so they can’t attend union events. All the wealth generated from these harmful and unjust practices flows directly upward to Khan, until it’s embodied in the Kismet, bobbing gently on the Mississippi River’s waves.

The Kismet would be an impressive feat of engineering, if it weren’t also an obscene monument to human greed and arrogance. It cost Khan an estimated $360 million of other people’s labor, and it’s 122 meters long (around 400 feet), with “six decks, four fireplaces, two fire pits, a spa featuring a hammam, or Turkish bath, sauna and cryotherapy chamber, plus a gym, basketball court and pickleball court. And, of course, a helipad,” according to the Florida Times-Union. It can host 12 guests in nine luxury cabins, along with a crew of up to 40 workers to ensure those guests never have to lift a finger for themselves. (Accommodations for the staff are less luxurious, and resemble walk-in closets with bunks.) On its face, the fact that all this is one guy’s personal possession is absurd—and really, it’s hard to imagine why anyone would want to own such a thing. Sure, you might have three different swimming pools on your boat, but you can only use one at a time, so what’s the point? Well, the point appears to be pure ostentation. A superyacht isn’t for enjoyment, at least not primarily; you could get the same basic experience with just a regular sized yacht, or a ticket on a high-end cruise ship. Like the old “I Am Rich” app on the Apple store, which did nothing but display an image of a red gem and cost $999.99, the Kismet is a status symbol. It’s all about the act of owning, and being seen to own. It’s about saying I am up here, and you are down there.

Khan isn’t the only one doing this. The week of the Super Bowl, his fellow billionaire Arthur Blank—one of the co-founders of Home Depot, and the current owner of the Atlanta Falcons—also pulled into New Orleans in a huge yacht called the DreAMBoat, which is only slightly more modest than the Kismet at 90 meters and a price tag of $180 million. Elsewhere, Mark Zuckerberg has a 387-foot yacht called LAUNCHPAD, and Larry Ellison employs a man to follow his 288-foot yacht in a speedboat and “retrieve the basketballs that go overboard” when he shoots hoops on it. Like with private jets, these vehicles are actively killing the environment everyone else needs to live in. Chris Armstrong, the author of A Blue New Deal: Why We Need a New Politics for the Ocean, describes owning a superyacht as “an act of enormous climate vandalism” and “the most polluting activity a single person can possibly engage in,” noting that billionaire Roman Abramovich’s various yachts “emit more than 22,000 tonnes of carbon every year, which is more than some small countries.” Really, there is no legitimate reason for superyachts to exist. They ought to be illegal to build, and unwelcome in every nation, principality, and port where they try to dock. Instead, they’re treated as guests of honor.

It’s Wednesday, February 5, and I’m walking up and down in front of the Kismet, furtively taking pictures for the magazine. Before long, I notice somebody who isn’t a tourist: an older Black man in a beanie and a windbreaker who’s also pacing around the area, trying to sell Mardi Gras beads. Nobody seems to be taking him up on the offer. I can’t tell for sure, but he looks like he might be homeless. At any rate, he doesn’t look like he’s doing too well financially. He’s taking a risk being here: earlier, the Louisiana State Police chased the trombonists, the guys who drum on buckets, and the other street performers off Bourbon Street, and there’s no telling who they’ll go after next. The whole situation—huge luxury yacht looming overhead, man hawking beads beneath—is grotesque. If you wrote it in a novel about inequality, your editor would tell you it’s too on-the-nose. I go up to the guy and ask how much the beads are. Three bucks, he says. I give him five, and wish I had more cash on hand. And because the whole thing is so unbelievable, I ask if it’s okay to take a picture. He nods, and strikes a pose:

Photo: Alex Skopic for Current Affairs

I haven’t been able to get that image out of my head since. In a remotely just or sane world, it wouldn’t be possible. But we don’t have one of those. We have capitalism, we have money, and we have economic class. Some people get to choose which of their nine shipboard cabins they’d like to sleep in each night, and some people have to hustle on the street for a few dollars to get by. That’s America for you, and that’s the Super Bowl, and it’s deeply, deeply sick and wrong.

The Warehouse

-jpg-1.jpeg?width=3000&height=2451&name=20250207_095141%20(1)-jpg-1.jpeg)

Photo: Alex Skopic for Current Affairs

It’s Friday, February 7, and I’m traveling down a series of desolate roads in an old car: first Poland Avenue, then France Road. This isn’t Europe, though. It’s an industrial area in Gentilly, on the eastern edge of New Orleans proper. It’s a bleak place, full of warehouses, freight trains, piles of gravel, and occasionally a spot where someone’s dumped a bunch of old tires and mattresses. If you killed someone, it’s the kind of place you’d come to dispose of the body. In the driver’s seat is Nathan J. Robinson, my editor-in-chief at Current Affairs and co-conspirator on this particular mission. We’re looking for the warehouse where Governor Jeff Landry hid all the homeless people.

Governor Landry, who I’ve written about on a few occasions before, has a nasty habit of rounding up the homeless citizens of New Orleans whenever the city has a big tourist event. Last October, when Taylor Swift brought her Eras Tour to town, the governor deployed “Troop NOLA”—a special police force of his own creation, consisting of 40 Louisiana state troopers—to conduct violent “sweeps” against unhoused people, expelling them from the area near the Superdome where Swift was set to perform. The term “violent sweeps” is redundant, since there’s no way to force people to leave an area peacefully, and Landry’s troops showed all the thuggish destructiveness that’s become familiar from this kind of police action. They reportedly destroyed or threw away the tents and other personal belongings of the people they were removing, including “identification documents, prescription medicine, clothes, and family memorabilia,” and directed people to stay at a site that “lacked trash cans, portapotties, hand washing stations, or water.” Notably, there was little pretense that this was being done for the good of the unhoused people themselves. Eyewitnesses say one of the Troop NOLA cops told a homeless person that “the Governor wants you to move because of the Taylor Swift concert,” and Landry’s own communications director said his goal was “ensuring New Orleans puts its best foot forward when on the world stage.” In other words, the priority was to ensure that visiting tourists didn’t have to see any visible reminders of poverty that might put them off their beignets.

Landry’s not the only one who thinks like this. Among the wealthy and powerful, the idea that the poor should be kept out of sight is commonplace. Back in 2013, when the aftershocks of the subprime mortgage crisis and Occupy movement were still being felt, a San Francisco tech executive named Greg Gopman expressed this view with unusual honesty when he took to Facebook to complain about seeing homeless people on the streets:

The difference is in other cosmopolitan cities, the lower part of society keep to themselves. They sell small trinkets, beg coyly, stay quiet, and generally stay out of your way. They realize it’s a privilege to be in the civilized part of town and view themselves as guests. And that’s okay[...]

You can preach compassion, equality, and be the biggest lover in the world, but there is an area of town for degenerates and an area of town for the working class. There is nothing positive gained from having them so close to us. It’s a burden and a liability having them so close to us. Believe me, if they added the smallest iota of value I’d consider thinking different, but the crazy toothless lady who kicks everyone that gets too close to her cardboard box hasn’t made anyone’s life better in a while.

Gopman’s comments became notorious, quoted everywhere from Slate and Lapham’s Quarterly to China Miéville’s landmark essay “On Social Sadism.” In 2016, he lost a cushy job at Twitter because of them. But it’s the comments underneath the original post that are really telling. One of Gopman’s friends wrote that “I don’t think you need to apologize for anything,” while another said that “It isn’t like you said anything many others in the startup community aren’t saying.” In other words, Gopman was not an aberrant individual within his class. He was a perfect expression of everything his class is, does, and believes.

Donald Trump, who came to New Orleans for the Super Bowl and is a key political ally of Jeff Landry, is another. Like Gopman, Trump sees the problem of homelessness not in terms of its effect on homeless people—he couldn’t care less about that—but as an inconvenience for other, richer people who may have to encounter homeless people. In a 2019 interview, he told Tucker Carlson that “When we have leaders of the world coming in to see the President of the United States and they’re riding down the highway… they can’t be looking at that.” More recently, he’s proposed moving the unhoused into “tent cities” on “large parcels of inexpensive land” away from urban centers—camps, if you will, where people would be concentrated. What he wants is nothing less than class-based segregation, and in New Orleans, Jeff Landry is pioneering the same approach.

This January, Landry announced that he had established a “transitional center” for New Orleans’ homeless population—which, like in the rest of the country, has been rising recently—and that he would soon be unleashing another wave of police “sweeps” and expulsions. If the term “transitional center” sounds like a euphemism for something uglier, it’s because it is. What Landry had really secured was a large, mostly windowless warehouse in Gentilly, where he intended to force all the homeless people he could find to go and stay until the Super Bowl was safely over. (It seems there was also a proposal to keep them on a barge floating in an industrial canal, but this was deemed impractical because it would be too difficult to stop people jumping overboard.)

Soon, details started to come out: the building was located at 5601 France Road, along the same canal. It was actually owned by the Port of New Orleans, but leased long-term by a shipping executive called Kevin Kelly, who also owns a plantation house and tried to buy some Confederate statues for $1 million in 2018; he’d be getting a lucrative sub-lease from the state, $75,000 a month. The warehouse was roughly 70,000 square feet in size, and could house 200 people. It would be patrolled by two armed security guards, each of whom would cost the state $117 an hour, and have two medical workers at $115 an hour, among several other staff. (Note that this is significantly more than guards, even armed ones, are typically paid in New Orleans. A recent job listing for Allied Universal states a wage of just $20 an hour—but things costing more than they normally would is a recurring theme with this project, as we’ll see.) The total price tag would be either $11.4 million or $16.2 million, depending on whether the facility stayed operational for two or three months. And the whole thing was possible because a horrible terrorist attack had just taken place on Bourbon Street over New Year’s Eve, allowing Landry to declare a state of emergency and do some discretionary spending. Never let a good crisis go to waste, they say.

When I say Landry meant to force homeless people to stay in his warehouse, that’s exactly what I mean. It’s a critical point that—at least for many of the people currently being kept there—“transitioning” into the “transitional center” was not voluntary. In a recent affidavit filed against the Louisiana State Police by several unhoused citizens of New Orleans, we can find firsthand testimony of exactly what an anti-homeless “sweep” involves:

At 6:50 a.m., officers began destroying those tents in which they did not observe any people. The officers were using knives and blades to sever the tents from their support poles and stakes. They would then pull apart the tents and leave them and any of their contents on the ground. During this time, I observed LSP Trooper Dixon and other officers speaking to a man in his tent. The officers left and the man quickly grabbed his bicycle and left his tent and the encampment. I could see that his tent was still filled with his belongings. Soon after this man left, two officers in dark blue uniforms began tearing apart his tent. I ran after this man to ask him what the officers had said to him. He told me that officers had told him that he could either get on the bus to the Transitional Center or he could go to jail. He had opted to instead quickly leave the camp and his possessions.

Destroying the few possessions that someone without a home still has is bad; threatening to arrest them simply for existing in a public space is worse. Nor was this an isolated incident. Christopher Aylwen, another of the plaintiffs, has a similar story to tell:

I am currently unhoused and have been unhoused for about nine months. During that time I have been sleeping on Decatur Street in the French Quarter. In the past 24-48 hours I did not see any signage posted on Decatur Street informing that I could not be there. At about 5:30 am on January 15, 2025, I was sitting on the curb near the corner of Decatur and Ursulines, speaking to an acquaintance. Two officers wearing khaki pants and blue tops walked up to me and identified themselves as policemen. They were later joined by officers in green uniforms who appeared to be Department of Wildlife and Fisheries officers. These officers told me that I needed to move because I was supposedly obstructing the sidewalk. The officers further stated that a bus was waiting to take me to a new facility. I replied that I did not want to go there. They told me, “It's either that or jail.” I said that I would move from the area, but the officers responded, “No, you can come with us or we'll cuff you and throw you in jail.”

Again, we see the threat of arrest used to “sweep” an area, and Governor Landry’s “new facility” used as the holding tank for everyone he doesn’t want around. The use of wildlife agents to police human beings is a grim touch—but even the word “sweep” itself is dehumanizing, implying that these people are simply dirt that shouldn’t be around.

In the end, the Guardian reports that the price tag for the so-called “transitional center” ended up being $17.5 million for three months’ operations, higher than either of the numbers Landry gave. So, for those of you keeping score at home, let’s do a little math. $17.5 million divided by 200 people is $87,500 per person. That’s the cost to keep any given individual in Landry’s warehouse for the allotted time. Meanwhile, the average monthly rent in New Orleans is $1,750. Take that $87,500 and divide it by $1,750, and you get exactly 50. So for the same price as keeping someone in a warehouse for three months, you could rent them a decent apartment and have them living there for 50 months, or a little over four years! Or, alternatively, you could get them a hotel room, where the utilities would also be included. At the downtown New Orleans Holiday Inn, you can get a room for anywhere between $132 and $379 a day, depending on the size and what’s included. For a conservative estimate, let’s round that up to an even $400. For $87,500, you could have someone stay at the Holiday Inn for roughly 219 days at $400 per day—the better part of a year. Not as cost-effective as renting an apartment, but still a lot better than paying the same amount and only getting three months on a cot in a warehouse. In fact, giving unhoused people free hotel rooms is exactly what the city of New Orleans did during the worst months of the COVID pandemic. When they did, there was virtually no homelessness (only about 30 people remained unhoused in a city of more than 360,000), until our politicians stupidly ended the program and brought homelessness roaring back. If Landry actually cared about poor people who need housing, he’d just run the same program again. Clearly, something else was going on here.

There’s reason to suspect that “something else” may have been good old-fashioned backroom dealing. As the Louisiana Illuminator reports, Landry’s warehouse is being run by a private contractor (of course!) called The Workforce Group, which provides “housing recovery” services like rebuilding homes after hurricanes. It’s a subsidiary of a firm called the Lemoine Company, which has donated $60,000 to the Republican Party of Louisiana since 2019. There’s also a family connection: according to the Illuminator, the head of the Workforce Group, Seth Lemoine, “is the stepson of Eddie Rispone, the Baton Rouge businessman who ran unsuccessfully for governor and was a key backer of Gov. Jeff Landry in his 2023 election win.” So here we have a private contractor that’s connected to the Louisiana governor through both political donations and a personal relationship, which received a lucrative contract on short notice from that same governor. By itself, that’s not evidence of anything illegal—but it certainly seems extremely unethical, and it may provide an explanation of why more sensible options, like apartments or hotel rooms, were rejected in favor of a very expensive warehouse.

When you take a look at the detailed breakdown of the Workforce Group’s proposal for the project—the initial one with the $16.2 million price tag, before the numbers even started to creep upward to $17.5 million—the impression of a highly unethical profiteering racket only increases. In fact, some of the line-items on the plan are downright disgusting. In the “equipment” section, it appears that the contractors didn’t sell the government items like cots for the homeless to sleep on; it rented them at a daily rate, which is multiplied by 60 on the relevant table. So you get line items like 200 cots at a rate of $20.48 per day, for 60 days, resulting in a total charge of $245,700 (or an eye-watering $1288.50 per cot!)—when, if you just go to Amazon or Walmart.com, a nice-looking folding cot can be purchased outright for anywhere between 60 and 80 dollars.

The full quote document can be found here, and if it conveniently disappears from the internet, we have copies.

The prices for other items appear similarly inflated, like the 225 “sleep kits” that apparently cost $318,937 ($1,417.49 apiece), or 20 “light towers” for $343,980. Again, there’s no proof of any criminal wrongdoing—but it looks like somebody was making money hand over fist here, and using the poorest and most vulnerable of us as an excuse to do it.

And what did the end result of all this outlandish spending look like? Well, it’s difficult to tell, because as the Guardian points out, the press “has not been granted entry to the site.” But we do have disturbing reports from people who’ve visited. Just a few days before the state police started sending people there, the chief of staff for a New Orleans city council member reported that “the warehouse had no floor, and I was told by [on-site] staff that the walls had no insulation.” For the first few days of operation, the Guardian notes that “the heat wasn’t working correctly, and indoor temperatures hovered in the mid-50s.” One local housing organizer says that “conditions in the warehouse were so difficult and cold that several people left” during the historic snowstorm that hit New Orleans in late January, preferring to take their chances outside. There are very few photographs online from inside the building, which is suspicious in itself. The few we do have come from a visit that Alonzo Knox, a Democratic state representative, made and posted to Instagram on January 23. In these, we can see rows of cots with cloth dividers between them; folding tables and chairs; a group of recliners around a single flatscreen TV; a sign that says “showers between 5:30 and 11:30.” In the post’s text, Knox claims that “issues with the sewer line and the heat were addressed”—but in the pictures themselves, everyone is still bundled up in their hats and coats, which makes you wonder whether the heat was really “addressed” adequately at all. Admittedly, the place looks better than sleeping on the street. But it also looks remarkably like the accommodations you’d find in a prison.

Photo: Rep. Alonzo Knox via Instagram

And so, on February 7, Current Affairs editor-in-chief Nathan Robinson and I set out to discover what we could about the benighted place. It was about a 15-minute drive from the populated center of New Orleans, and the sheer distance and isolation might be the most important thing to know. France Road really is in the middle of nowhere, and for anyone trying to leave the “transitional center,” it would be a hell of a hike back to civilization—especially if you happened to be an older person, or dealing with any kind of illness or injury. As the New York Times points out, “The closest fast-food outlets are a half-hour away on foot,” and most of the nearby roads have no sidewalk. That doesn’t deter everyone; along the way, we stopped and talked to a man who said he was walking from the shelter to Walmart, which is about 1.5 miles off. He said he didn’t mind the long walk, but most people probably don’t share his opinion. More importantly for Jeff Landry’s purposes, it’s 6.3 miles from the warehouse to the Superdome, so it’s highly unlikely that anyone from one place would show up at the other. On the day of our visit, ours was practically the only regular car around. Mostly, huge tractor-trailers barreled along, carrying construction materials and presenting a menace to any would-be pedestrian. Ironically enough, the closest business is one that repairs yachts; maybe Shahid Khan stops in when the Kismet springs a leak. There is a residential neighborhood nearby, but none of its roads connect to France Road. Instead, there’s a railroad in between. The shelter is literally on the wrong side of the tracks, and given that it was Jeff Landry and his associates who chose it, it’s hard not to see that as deliberate.

Image: Google Maps. Circle added for emphasis.

Photo: Alex Skopic for Current Affairs

When we finally arrived and pulled into the gravel parking lot, we didn’t get far. There was a uniformed cop in an unmarked car—a green Lexus SUV, by the way—waiting, who had clearly been posted there to deter journalists and other undesirables. Nathan kept the engine running, just in case things got difficult, and I walked over. The officer asked who I was there to see, and if I’d been clever, I would have said a common name like “John” and maybe got in. Instead, I stupidly told the truth, and she told me the same thing as the reporters from the Guardian and the New York Times: no press access, unless “the woman who runs the place” said so. I asked to talk to this woman; the cop said she wasn’t there. I asked when she would be there; the cop said she didn’t know. At this point, it was clear that this was a stonewall, and we wouldn’t be finding out much. So I snapped the picture at the top of this section, and we got out of Dodge. But it wasn’t a complete waste of time.

In itself, the fact that the Louisiana government has posted a cop specifically to keep journalists out is telling. Hiding a location from the press is almost never a good sign; presumably if the site were a great success, the government would want to brag about it. And if you zoom in a bit on the picture I managed to get, you can see a few people sitting around a pair of sliding glass doors at the front of the warehouse. These are the same people the reporters from the Times describe: “security guards” who “adjudicate who comes in and who leaves.” It’s not clear what the “adjudication” involves—who can leave, and when, and why? But there is a system of control in place. To some extent, at least, the warehouse resembles a prison because it is one. Or, more accurately, it’s a modern reincarnation of the poorhouse—a Victorian pseudo-prison where people were sent specifically because they were poor and couldn’t pay their debts. You might remember it from Charles Dickens’ novels, but now it’s back.

The Men with Guns

Heavily armed FBI agents gather a few blocks from the Current Affairs offices. Photo: Alex Skopic for Current Affairs

And who, we might ask, keeps all this running smoothly during Super Bowl season? Who guards the superyachts on the river, and who forces the homeless into the warehouse? Why, the men with guns do. For the week of the big game, the New Orleans Police Department told reporters there were “Approximately 2,000 law enforcement officers” in the city. That’s an additional 200 state police and 300 National Guard members, on top of the NOPD itself, the FBI, the Department of Homeland Security, and various other acronym-laden agencies. That’s more than the militaries of some small nations, and it certainly felt like an armed occupation. Just walking through the French Quarter, you could encounter every conceivable subspecies of cop: traffic cops, motorcycle cops, cops on horseback, cops in helicopters circling ominously overhead, cops on bicycles wearing high-vis vests, and so on. It might be an exaggeration to say there were cops posted on every street corner, but not by much. One night I saw a gaggle of cops on Bienville Street working a metal barrier that clanked up and down; they’d raise it when they saw a car coming, crowd around the hapless driver, and have a drug-sniffing dog circle the car until they were satisfied, then clank the barrier down again. But the most startling were the soldiers serving as cops, decked out in their camo uniforms and bulletproof vests and equipped with weapons and vehicles designed for war. Some of them looked to be about 19 years old, which is alarming when they’re holding semiautomatic rifles. All of this, apparently, was intended to make everyone feel safe and secure.

Maybe it’s just me, but I don’t actually feel safer when I’m surrounded by men with guns. After all, that’s the reality that euphemisms like “law enforcement officers” or “security forces” are designed to obscure: that these are armed agents of the state, who could kill you at any time if they decided to. Every week, practically, there’s a news story about some cop who panicked and unloaded a magazine full of bullets in the general direction of what scared him, or mistook some innocuous object in someone’s hand for a weapon and killed them on the spot. Walking past a cop is like walking past a large dog who isn’t on a leash; you probably won’t get mauled, but you never quite know. In New Orleans, it seems that the sheer amount of coppage going on actually deterred the tourism it was supposed to protect. As the local Gambit magazine reports, “law enforcement outnumbered tourists on Bourbon Street” at some points:

“The military presence has completely changed the feel of the Quarter,” musician Dr. Sick told Gambit on Saturday evening. “The bright security lights are blinding the audience at one of the clubs where I play, so we made makeshift drapes to shield their eyes[...] Personally, I do not feel safer with the young members of the National Guard standing around with machine guns,” he added.

Some local business owners even report that they lost money as a result of the security crackdown:

“If I was a tourist, I wouldn’t want to be walking past all these army tanks... it was like a warzone,” said Lyla Clayre, who owns an art gallery in the Quarter a half block from Jackson Square. Law enforcement set up a checkpoint in front of her business, which meant there were four heavily armed members of the National Guard posted up at her door throughout most of the week — not exactly the welcoming environment one might want for their watercolor painting store. Her bottom line bears that out. On an average Saturday, Clayre said, her business makes around $1,000. On the Saturday before the Super Bowl? “We made $100,” she said.

The only things that really seemed to do well during the Super Bowl week, in fact, were the big corporate events from out of town. There was the 60-foot tailgate truck sponsored by Smirnoff, the “Madden Bowl” video game tournament hosted by EA Sports, Shaq’s Fun House, and PepsiCo’s “Chips and Sips” pop-up village—a bizarre imitation French Quarter built next to the actual French Quarter on Decatur Street, the very place Christopher Aylwen was driven away from by the cops. The bigger and more commercial something was, the better it did, all the way up to the NFL itself—the biggest corporation of them all, and one that’s notorious for mistreating athletes and other workers. Meanwhile, the less money someone had, the more they suffered, from the little bars and shops who saw their business choked off all the way down to the unhoused people who were driven away by the police. The class divide was in full effect, and enforced at gunpoint.

Photo: Nathan J. Robinson for Current Affairs

How Much Longer Will We Tolerate This?

The Super Bowl this year was a carnival of greed and depravity, but it’s not unique in American life. Far from it. The whole country is like this now, and getting more so by the day. The rich are getting richer and more powerful at an ever-accelerating rate, with the first trillionaires expected to emerge any moment now. Some of them have moved beyond yachts, and want luxury spaceships, which the rest of us will doubtless have to build for them. Meanwhile, more and more ordinary people find themselves unable to afford food, medicine, and housing—the most basic necessities of life. We’re hurtling toward a point where a handful of people have everything and the vast majority have nothing. Morally, that’s vile. Practically, it’s not a stable or sustainable way for a society to operate. The Marxists believe that capitalism’s tendency to accumulate more and more wealth in fewer and fewer hands will eventually lead to a breaking point where revolution is inevitable. Historically, I think calling anything “inevitable” is a bad bet—but looking at the Super Bowl and all the horrors that surround it, it does make you wonder how much longer people will tolerate living like this. The old catechisms about American capitalism being a wonderful system of freedom and opportunity, where hard work is rewarded and the wealth trickles down, are wearing thin. It’s increasingly obvious that it’s nothing of the kind. It’s a yacht, a warehouse, and a man with a gun. How much longer will we let it go on?