The Extreme Danger of Dehumanizing Rhetoric

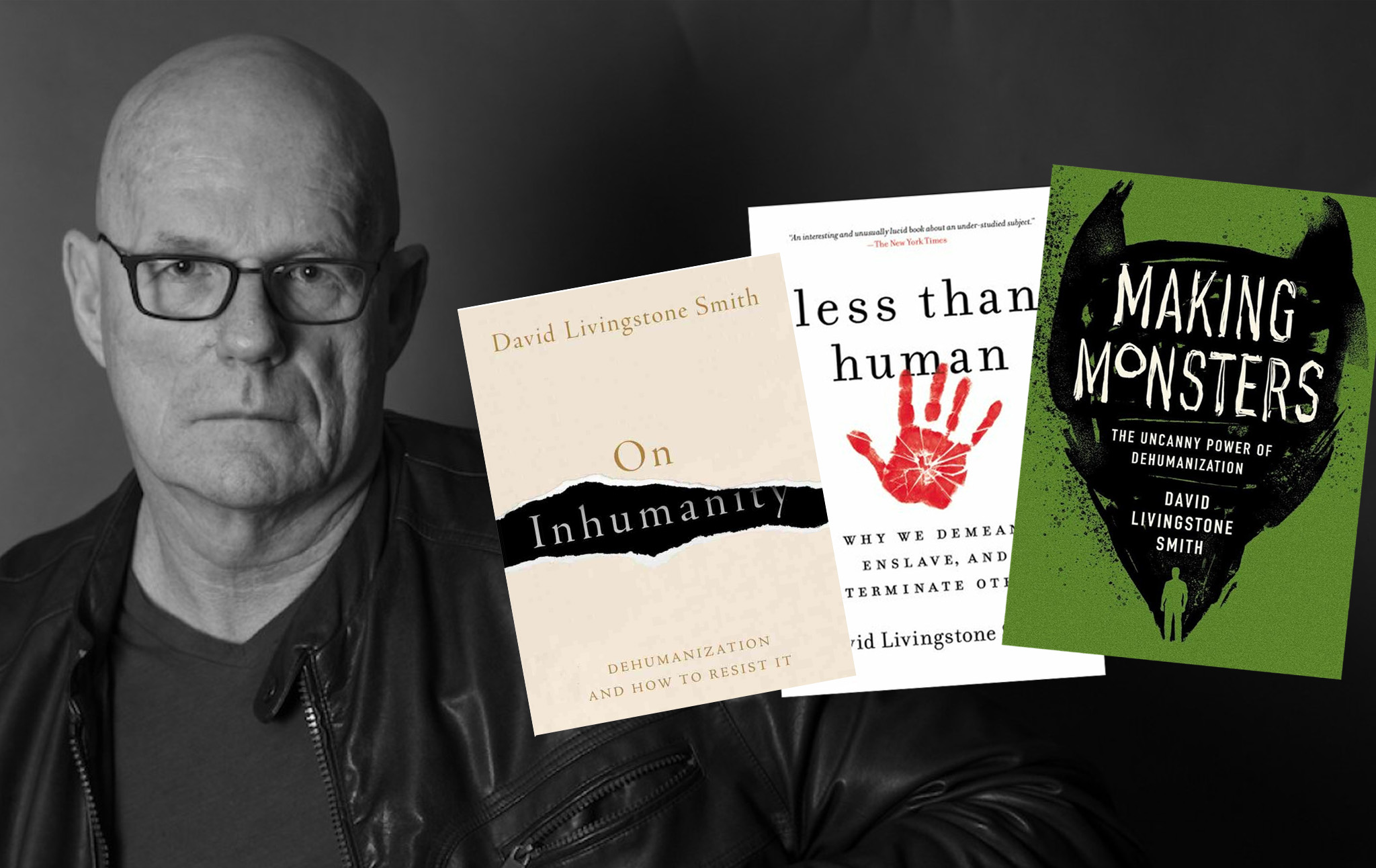

David Livingstone Smith, one of the world's leading scholars on dehumanization, explains what it is, why we're so prone to it, and how to resist it.

David Livingstone Smith is one of the leading scholars of dehumanization in the world, the author of books like Less Than Human: Why We Demean, Enslave, and Exterminate Others, On Inhumanity: Dehumanization and How to Resist It, and Making Monsters: The Uncanny Power of Dehumanization. He joins us today to discuss how the dehumanization process works and why it's so dangerous when we start to use dehumanizing language, which we can do without noticing it. Prof. Smith warns that while the point seems obvious, many of the worst atrocities are committed by those who are fully convinced they are on the side of the good and righteous, and any of us can become a dehumanizer. We discuss examples from the treatment of Palestinians as animals to the worst historical genocides to parts of the American right treating leftists as "unhuman" enemies of civilization. Prof. Smith explains how the process works and how we can resist it.

nathan j. Robinson

A great deal of your work has been concerned with this concept of dehumanization. What is it about this one concept, this one phenomenon, that has made it so important that you have dedicated so much time to trying to fathom it? [...] You argue that this phenomenon of dehumanization is at the root of so much of the worst of what humanity does. If we want to look at all the worst atrocities in history, and if we want to prevent atrocities in the future, we have to understand what this is, how we do it, and why we do it.

Smith

I think it's really important to invest our intellectual resources carefully in things that matter to the welfare of living things on this planet. So, in philosophy, generally, I think there's often—and this is incentivized by the profession, by the way—a shameful squandering of intellectual resources that could better and more productively be applied elsewhere. So, that's why I devote myself to dehumanization. The first thing I said was about how the work on it hasn’t been good and adequate, and it's terribly important. It's played such a role in genocides and war and other forms of atrocity that human beings have perpetrated against one another. It's vital to understand, and I think it's particularly important at this historical juncture and in light of impending climate change, which will produce social and political effects that will be a perfect storm for producing the very worst things that human beings are capable of doing to one another.

Robinson

I want to ask you more about that later in the program. Let's start with what people's popular conception of dehumanization might be, and some of the ways in which you get us to think more deeply about it. I think if I were to ask someone to tell me about an example of dehumanization, they would probably go to the paradigmatic example, one of the worst examples in history, which is the Holocaust. They might tell us about the Nazi dehumanization of Jews, seeing Jews as untermenschen, as less than human. I think people might have a good understanding that the Nazi view of Jews as not being fully human clearly played a significant role in the project to exterminate them.

One of the insights in your books that will make people uncomfortable is you write that, yes, that's a very clear example. But if we're going to talk about World War II, in fact, all parties in the war, not just the Nazis, were engaged in dehumanization. In fact, as the Nazis dehumanized Jews, so did the Soviets dehumanize Germans. And it sounds strange to say “dehumanize Nazis” because I think that people do very easily say, the Nazis are monsters and are really not human.

Smith

Yes, that's right, and that's a mistake. I think that's a fatal mistake to dehumanize the dehumanizers. It's exactly the wrong attitude to take. I think we need to look at the Nazis and think of them as holding up a mirror to what we're capable of doing. They were not that different from anyone else. So, yes, popular ideas of dehumanization are all over the map. The term entered the English language in the early 19th century, and it has just accumulated a whole number of meanings, extending from Auschwitz to the open-plan office.

Robinson

Right. People will talk about dehumanization as "de-individuation," or seeing people as numbers, like how a bureaucracy can be dehumanizing.

Smith

So often, it casts way more heat than light, and it's often mixed up with what I call nearby phenomena. I think it's important to refrain from doing this. Nearby phenomena like racism, classism, homophobia, misogyny and so on are all really important things, and they all deserve to be studied properly. But we don't gain anything from lumping them all together under a vague umbrella of dehumanization.

So, when I talk about dehumanization, I think of something very particular. It’s a very particular kind of phenomena which deserves to be treated on its own terms. And as you said, when you're talking about World War II, yes, all parties engaged in dehumanization. And one of the things that's really crucial to get a hold of is it comes really easy for us. It's not like there are the dehumanizers and there are the rest of us, the “normals.” one could say. No, it's not like that at all.

Robinson

At various points, you talk about the U.S. wars in Japan, Vietnam, and Iraq. And if you look back at how Americans talked about the Japanese, one of the scary things is how quickly dehumanization can set in. A group of people who many Americans might not even have had very strong opinions about at all up to the Pearl Harbor attacks are suddenly a race of insect people. The propaganda and the language are really disturbing when you excavate it.

Anti-Japanese propaganda from World War II

Smith

It's exterminationist language, some of the stuff from that era. Yes, so we can slip into it very easily because we have certain psychological propensities which, under the right circumstances, make it possible for us to think of other members of our species as less than human creatures. And, of course, propaganda plays a big role in it. Skillful propagandists know how to induce these sorts of attitudes.

I should really define what I mean by dehumanization. Dehumanization, in my view, is the attitude of conceiving of others as subhuman creatures—less than human creatures. So, it's attitudinal. It happens in people's heads. And that distinguishes my view from many other views that see dehumanization as a purely rhetorical phenomenon, simply the use of slurs, or dehumanization as a kind of activity, treating people in cruel and degrading ways and so on. I see it as attitudinal. It happens in people's heads. But—and this is where I had problems with the social psychologists—one of several issues I have with them is that you cannot understand it just by looking at what's going on in people's heads. You have to look at what people's heads are in.

In other words, you have to look at the social and political environment in which people are embedded. You have to look at the forces impacting human psychology. Human psychology is essential for any kind of explanation of behavior. Without psychology, we don't behave. It's necessary, but it's not sufficient. So, we need to understand that interface.

Now, you refer to a number of examples, and all of those examples have something in common, and that's the connection between dehumanization and racialization. There are forms of dehumanization which are not associated with notions of race, but the big, dramatic examples that we're all familiar with are the paradigmatic examples, like what I concentrate on in my work: the Holocaust, or more broadly, European antisemitism from the Middle Ages onward, and anti-Black racism in the United States as it manifested after the Civil War when you had the most vile kind of dehumanization of African Americans. So, race and dehumanization are intimately entwined.

It's very revealing that Americans in World War Two tended not to dehumanize Germans, but certainly dehumanized Japanese people. So, we can ask the question, why is that? Why is dehumanization so linked with racialization? (I use the term racialization, by the way, because I don't believe in race, but that's another story.)

Why? Well, you have to understand how race works, how racialization works. In my view, the notion of race, at least a very prevalent notion of race, today and historically, involves the following components: It's the idea that there are a small number of fundamentally different kinds of people, that belonging to one of those kinds is a matter of descent, and third—and most controversially, when I speak to my colleagues—the notion is inherently hierarchical. There's an idea of higher and lower human beings.

We're not to dehumanization yet. Of course, the racializers typically modestly place themselves at the top of the hierarchy. Sometimes this is very explicit, and whoever is being enslaved or colonized goes at the bottom. So, we have this hierarchy within the category of the human. In my 2020 book, On Inhumanity, I described dehumanization as racism on steroids. That is, when we racialized people, we demote them in the category of human, and when we dehumanize them, we take it further. We take it that they don't belong to the category of human at all. There's something more primitive, something of lesser value, even of a despised race, and that makes dehumanization particularly dangerous and toxic.

So, people don't wake up in the morning and think, "those others: they look different, they talk different, so they must be subhuman." That is not how it works. The way it works, and every historical example that I've studied conforms to this, is through what I call epistemic deference. We hold certain people up as authorities, as having inside knowledge, as having special knowledge. This is vital to human culture. We couldn't get on without it. And once people are placed in that position, whether they merit it or not, it is reasonable and rational for us to defer to them because they're the experts—they're the people who are supposed to know. We do this all the time. When we're children, the experts might be our parents. Or, when I grew up in the Deep South in the '50s and '60s, it was the local pastor or sheriff, the person who's in the position of being the person who was supposed to know.

That's important because such people can make it possible for us to override our perceptions. So, one of the most distinguished biologists in late 19th century Germany was a man named Ernst Haeckel. In his textbook on biology, there is an illustration of the great apes, and that illustration included the orangutan, the chimpanzee, the gorilla, and the African man. Biology students in Germany were not well-placed to challenge that. That was the great Ernst Haeckel. So, it could be a scientist, it could be a religious leader, it could be a political propagandist like Joseph Goebbels, it could be a right-wing radio jock. Whoever is in that position is endowed with the power to induce us to think of others as less than human, to play on our sensibilities and our psychological dispositions.

Racist illustration from Haeckel's book, 1870

Robinson

What you're saying there reminds me of what I’ve read in a fair number of Vietnam War memoirs. A couple of times a version of the same story came up: a soldier went to Vietnam thinking that they were going to liberate the Vietnamese, and then when they were there were told, essentially, to not use the term “Vietnamese,” and then were given a list of acceptable racial slurs. You could only speak in slurs about the Vietnamese. They were not regarded as human.

But then there's that process that you're talking about, which is that wasn't the natural inclination of the soldier who shows up in Vietnam. That's the instruction that you're given immediately by a figure in authority. I suppose because the military is such a hierarchical organization, it would explain why it's much easier to do this in the military. You get handed your orders, and one of your orders is, don't regard these people as people.

Smith

That's right. We find the same thing among the Einsatzgruppen, the mobile death squads that followed the German army into Eastern Europe and were responsible for the Holocaust of bullets. Before the extermination camps were built, it was bullets in the back of the head of thousands, or sometimes tens of thousands, of men, women, and children at once. They were explicitly instructed: you are not to conceive of Jewish people as people. So, people need to be induced into doing that. And they need to be induced because, as hyper-social animals, we are exquisitely attuned to indications of humanness in one another. That comes naturally to us; the sight of a human face, the pair of human eyes, and bang, it's automatic.

Robinson

This is almost an encouraging finding in a certain way. It's not that it's not a natural phenomenon—obviously it is natural. But it suggests that there is a powerful counter-current, or counter-instinct. It's not like we constantly have to be fighting the ordinary drift towards dehumanization.

Smith

Yes, that's just something that that many people don't get. But paradoxically, it's our very tendency to humanize which produces the most dangerous and toxic effects of dehumanization.

Robinson

You'll have to explain that.

Smith

So, when I wrote my first book on dehumanization, Less Than Human, which came out in 2011, I used to think the whole story of dehumanization went something like this: When we dehumanize others, we attribute to them the essence of a non-human animal, that is, irrespective of how they appear, what they really are on the inside is something akin to a rat or a cockroach or a bloodthirsty, dangerous predator, or whatever.

Then years later, approximately, I revised that view somewhat with two books that fell out right on the heels of one another. I realized that this wasn't quite right for two reasons. One, I call the problem of monstrosity, and the other, I call the problem of humanity. Let's start with the problem of humanity. So, again, if we look at real historical examples, what we find is that people who dehumanize others alternate, typically, between regarding them as human and regarding them as subhuman. Sometimes this happens in the space of a single sentence, and that's quite explicit. This also happens implicitly. Dehumanized groups are often, for instance, accused of being criminal. This is just very standard.

We find it in my two paradigmatic examples: Black people, particularly Black men, were supposed to be inherently criminal, and the Nazis presented Jews as inherently criminal as well. And the same in Myanmar with the Rohingya. We can find it all over the place. But only human beings can be criminals. Cockroaches can't be criminals, and rats can't. So, any decent theory of dehumanization has got to explain that, and that observation has led some people to be really skeptical of the very notion of dehumanization. The idea being, but they're talked about as though they're human beings, so, when dehumanizers call them cockroaches, they can't really mean it. They're just trying to use words as a weapon of degradation.

I don't think that's it. The problem of monstrosity: if we look at the most horrible forms of dehumanization, say those bound up with genocide, what we typically find is not simply that the dehumanized other is described as a non-human animal, but as a monstrous or demonic entity, a pure embodiment of evil. Now, in the Middle Ages, people were fine talking about demons. In the antisemitic literature of, say, the 14th century, Jews were routinely described as demonic beings. Doesn't quite cut it in the secular world today. It does cut it among religious conservatives of certain stride. So, there are equivalents. Nazi is often an equivalent, by the way; to say someone's a Nazi is to say they're rotten to the core, they're evil to the core, and so on.

Now, how do we explain these two things, the problem of humanity and the problem with monstrosity? Well, I think the best story is this. I have to go to an academic mini-industry called Monster Theory. Monster Theory is mostly in literary studies, but the theorist who's influenced me most is a philosopher named Noël Carroll. He looks at horror fiction, and one of the things Carroll tries to do is set out the conditions for being what he calls a horrific monster, the kind of monster you see in horror flicks and so on.

Carol says that there are two requirements; this is the job description: The monster has to be physically threatening—monsters want to hurt you—but that doesn't distinguish monsters from all kinds of other beings that are perfectly ordinary, like serial killers and so on; the monster also has to be—now I depart from his language— metaphysically threatening. (He uses the term cognitively threatening; I think my term works better.) A being that's metaphysically threatening is an impossible combination of incompatible types of things.

So, think of zombie flicks. Zombies are simultaneously alive and dead. That's impossible. It crosses the boundary of how we conceive of life and death, and it's not that they're partially alive and partially dead. They're totally alive and totally dead. They're decaying corpses that walk around. Or, think of a werewolf, which is wolf and human simultaneously.

Okay, so now we've got a kind of handle on monstrosity. Here's what I think happens and that is my best explanation of the problem of humanity and the problem of monstrosity: on the one hand, as exquisitely social beings who are hypersensitive to the humanness of others, as beings who, when we see a human face or a pair of human eyes, bang, we see them as human—we can't help it, we can't turn it off—but on the other hand, as beings who defer to those who try to convince us that these others are subhuman creatures, what happens is we have a contradictory representation of those whom we dehumanize.

When we follow the experts, and they say the Jews are untermenschen, or Black men are beasts, we've got that, but we've got this countervailing force—our perceptions of the other as human—and then we get this kind of superimposition of these two representations, and that transforms them into monsters. And that is really evocative of the very worst violence we can see because if you're fighting monsters, there's no quarter and there's no mercy.

Robinson

I couldn't help think of a contemporary example that you've written about yourself, which is that after the October 7th attacks against Israel, one of the Israeli Defense Minister famously, or infamously, said that we're fighting human animals, and we'll respond accordingly. And a lot of the rhetoric in Israel about Palestinians, generally, and definitely about Hamas specifically, is that while maybe you can make a distinction between Palestinians and Hamas (which they don't always do), when you're talking about Hamas specifically, then you are really talking about monsters in human form.

Smith

Yes. Actually, there were two steps to this. The human animal statement was from immediately after the atrocities on October 7th. And as soon as I heard that, I said, oh boy. He didn't say wicked people, and he didn't say animals. He said human animals, and that's the prelude to monstrousness. Then shortly afterwards, it was Yoav Gallant, the Defense Minister, who said, we are fighting monsters. That transition was entirely predictable. When you get that kind of rhetoric, you just know there will be terrible atrocities following from it.

Robinson

This is partly to do with the fact that we devalue animals so much. You write that if we treated animals well and elevated the status of animals, then it wouldn't be nearly so much of a license for atrocity to compare a human being to an animal. But once a person is a creature rather than a full human being, anything can be done to them in a situation where you feel like you're defending yourself.

Oftentimes, I'm fascinated by how in situations where one party is in the right, in that they are defending themselves, that can actually contribute to their committing atrocities. You mentioned the Allies in World War II.

Smith

Yes. And virtually every genocidaire—in every genocide, the perpetrators' attitude is of righteousness. They're saving the world from evil. Genocide is very often a highly moralistic affair, and that is entirely compatible with dehumanization. Killing the monsters.

Robinson

It's striking just to linger a little bit on the case of Israel. I think it's such a strange example in a certain way because you would expect that no people would be more sensitive and aware of the dynamic of dehumanization than the state founded in the aftermath of the Holocaust, the most infamous example of this in history. And yet, I've heard Israeli politicians essentially using Nazi rhetoric, even saying things like the children themselves are the future terrorists, and so we might need to eliminate the children as well, the same kinds of things that you would hear from Himmler.

Smith

Yes, that's absolutely true, and that should be a very useful corrective to the naive idea that anyone, or any group of people, is immune from dehumanization as perpetrators, or indeed, as victims.

Robinson

Because we do tend to think that perpetrators are monsters and not people. One of the key insights from your work is to not dehumanize the perpetrators either. When you dehumanize the perpetrators, then you're incapable of the self-scrutiny necessary to understand the process by which an ordinary person becomes a dehumanizer.

Smith

That's quite right. That's why I say we need to look in the mirror that they hold up to us. And of course, it feels good to say that Hitler was a monster. I'm Jewish, so it's important to get my bona fides there. It produces this nice flow of self-righteousness, and you feel good because you're reassuring yourself that Adolf Hitler was essentially, fundamentally, different. You're creating this kind of moral distance, and that's not good. That's perpetuating the phenomenon which we should all be working at trying to at least constrain, if not eliminate.

Robinson

When you start to think about dehumanization as a distinct category of thing, you can start to be able to identify it kind of precisely when you see it. You cited an example of Donald Trump. At a rally, he was talking about a nursing student who was killed by an unauthorized immigrant, and he said, “she was barbarically murdered by an illegal alien animal.” He said, “and Democrats said, Please don't call immigrants animals. I said, No, they're not humans, they're animals.” And I take it that you do regard dehumanization as a particularly dangerous kind of thing to engage in, that to say they’re a monster or an animal is worse than just saying this was a psychopath or a psychopathic criminal.

Smith

Yes, but it's really tricky, because just as “Nazi” can be seen as a secular euphemism for demon, psychopath can have that vibe too. But your general point holds. So, if he had said something like, to use the term that Republicans are fond of using, a violent “illegal”, that's not quite the same as not human. An animal. He's being really explicit.

Robinson

He's like, they would like me not to call him an animal. I am going to. I am specifically saying animal.

Smith

That's so typically Trump, yes. Because often what happens is—although this has been changing since Trump—it's not seen as socially acceptable to be explicit about it, so political propagandists just pepper their speeches with terms and the audience can connect the dots. When you talk about “swarms” coming in over the border, “swarm” is an animalistic term. When you talk about “breeding grounds” of terrorism, again, we have an animalistic term. So, you don't have to necessarily come right out and say it, but of course, it’s much more easily identifiable, and it's easier to protect ourselves from it when it is explicit.

Robinson

I want to quote from a speech that was given at the National Conservatism Conference recently:

"We don't negotiate with globalist Neo Marxists. We don't negotiate with the political version of an autoimmune disease. In a word, ladies and gentlemen, we don't negotiate with unhumans... because that's the stake of this battle, humanity versus unhumanity. Populist nationalist versus atheist Marxist globalist. strength, beauty and genius versus weakness, ugliness and stupidity. Civilization versus barbarism."

Well, civilization versus barbarism is kind of classic, but the speaker even knows that he's adding something by saying “unhuman” because he says, “we don't negotiate with unhumans.” He said it makes a difference that I'm stripping the enemy of their humanity.

Smith

Yes, it certainly does. When you start calling people the political version of an autoimmune disease, you're there. Who was that?

Robinson

Jack Posobiec. He's written a whole book called Unhumans about the left.

Smith

My God, I'm going to have to check that out.

Robinson

This is grist for your scholarship, I feel like.

Smith

Yes, there will be a few Substack essays on that one.

Robinson

But obviously, political rhetoric in the United States is often heated. The left believes that the right is a threat to democracy. The right believes that the left is eroding the foundations of Western civilization, etc. But it does seem like when we get to the sort of things that Posobiec is doing there, that Trump is doing, we take it into very dangerous territory because of what it licenses.

Smith

This is, in my view, a fascist style of politics, and that style of politics is particularly associated with dehumanization. And we've had examples, such as the one you just read to me. So yes, this is very dangerous.

Robinson

You've thought a lot about the step-by-step process. You mentioned one aspect of it, which is what you call the epistemic deference. There are authority figures, and they help to define our world for us. If we're an attendee at the National Conservatism Conference, the speakers are now giving us license to think of people as less than human. Tell us more about how we can be on guard for the process by which this tends to occur.

Smith

The first thing to say is there isn't any vaccine. This requires vigilance. We can push back against dehumanization on a number of fronts, and some of them involve self-knowledge, which I think should be part of everyone's education—not what they learn in Psychology 101, but sort of a self-defense manual. What is it about us and the way that we think that makes us vulnerable, so we can track ourselves.

The other is historical education. I think this is the most important. First, if we look worldwide, nations are generally born in violence and perpetuated in violence, and everyone's got blood on their hands. Every group of human beings does somewhere along the line. So, it's really important for people to know what they, whoever they are, have done. And I can assure you that this does not enter very much into education in the United States. My undergraduate students at a New England liberal arts college really have no idea. You have no idea of the history of race, and no idea of how race and colonialism tip into dehumanization.

So, that's important too. These are like prophylactic measures. One of the things which I think is super important has to do with being able to identify the kind of propaganda which leads us down that path to dehumanization. And here I'm very influenced by a paper that was published in 1941 by a British psychoanalyst named Roger Money-Kyrle. He was a psychoanalyst and had two PhDs in philosophy and anthropology, so he was a smart dude. He went to Germany in 1932 to listen to Hitler and Goebbels making their stump speeches, and his paper is all about his experience. A lot of stuff is barely intelligible in the paper, but I think he makes one very important point, which in fact, is an extension of some of Freud's work.

He says, when I listened to Hitler and Goebbels, they always did the same thing. The first step was to make the audience feel helpless, endangered. And he actually goes through this in greater detail. He said, first, to make them depressed: we were humiliated by the Treaty of Versailles; we're in the midst of economic crisis; law and order has gone out the window; we're a mess; we've let Germany down. So on and so forth. And then, as Money-Kyrle put it, when the audience is rolling around in an orgy of self-pity, he switches to a paranoid thing. Well, it's not your fault, really. It's the Social Democrats and the Jews. They're the enemy. So the audience then gets worked up into fear. I think fear is greatly underestimated as a powerful political force. And then Hitler did two things. One was to give them a pitch about the Nazi Party: from small beginnings, we've become a mighty force; and then an appeal to German unity. And if you've taken the bait at the beginning, you're a sucker for the final step.

Now, back in 2015, I watched Trump's speech when he came down the escalator to throw his hat into the ring as a potential Republican nominee, and I was really astonished. He followed that playbook to the absolute letter. First it was we’re the laughingstock, everyone is exploiting us, and a once great nation has fallen on hard times. Then he switches to the familiar theme: the Mexicans are pouring into our country—rapists and murderers. So, that's the paranoid moment, and then only one man can make America great again: Donald J. Trump.

And so I noticed, and I thought, holy shit, this is a very dangerous man. He knows what he's doing. I think what's going on with him is he just has a gut instinct for what moves people, and he uses it. But of course, all my well-meaning liberal friends metaphorically patted me on the head and said, silly boy, he's a clown, this is just entertainment. So, being able to come around and be able to spot this stuff while it's happening and push back, to recognize that one is being drawn in—and this is powerful stuff—is, I think, really important for protecting themselves.

Robinson

Yes, I think to have the humility not to be confident that you would never be taken in is very important. A small note: I don't know if it's ever been completely confirmed, but Vanity Fair reported in 1990 that Ivana Trump had claimed that Donald Trump read a book of Hitler's collected speeches and kept it by his bedside.

Smith

I wrote a Substack essay about that, and I used to think that it's just that he had the salesman's instinct, but I'm not so sure. Actually, there were a couple of reports of him having read Hitler's speeches.

Robinson

Well, just to be clear, the explanation for it that I think is most plausible is that Donald Trump thought to himself, wow, Hitler was a very good salesman—I don't agree with him, but a very good salesman, and I need to study whatever his methods were.

Smith

Yes. I think that's most plausible, too.

Robinson

I think he may have thought, wow, that guy could make a speech.

Smith

He'd be right.

Robinson

And these are techniques that, if you want to persuade people to join you in your mission to make America great again, you can use. As you say, there's no vaccine, but as we conclude here, one thing that has struck me in reading your work that we all kind of have to agree to do something really difficult, which is to commit to never dehumanizing anyone, regardless of the temptation. There's a temptation when you read about some horrible serial killer, when you read about Nazism, when you read about Japanese atrocities towards prisoners of war, or if you are highly critical of Donald Trump. It's really hard because you always want to carve out an exception. You always want to say, except for the real monsters, and as I mentioned earlier, except for Hamas, or except for Netanyahu. So, it's really tough to say, I will never dehumanize anybody, even the worst villains. But if you do that, if you make that commitment, that might be as close as you can get to an intellectual vaccine.

Smith

Yes, that's right. And to do that effectively, you have to catch some stuff upstream. There are certain forms of speech, for instance, which slide us right into dehumanization. It's what philosophers and linguists call generics. A non-political example is to say “dogs bark.” You're not saying some dogs bark. You're not saying all dogs bark. You're saying dogs bark. And research indicates that way of speaking encourages us to essentialize. Now, we find this kind of discourse in politics all the time: “the Democrats,” “the Republicans.” Well, I think we need to refrain from that. You could say most. You could say all, if that's what you mean. You could say some.

Robinson

Particular ones.

Smith

You could name names.

Robinson

You could say, this person; these are examples of someone doing this.

Smith

Yes, but that broad brush approach, the generic approach—the Democrats, the Republicans—that's dangerous.

Robinson

It's very hard to get out of saying things like “dogs bark,” though, without being extremely pedantic in your day-to-day speech.

Smith

Yes, but you see, with dogs bark, we don't have to. That's harmless. But “Jews are greedy” is not harmless at all.

Robinson

And then we certainly shouldn't do what Thomas Friedman of The New York Times did a couple of months ago, which is to write a column in which he decided to categorize each Middle Eastern country by what kind of animal he thought it was associated with.

Smith

Oh, my God. Yes, I remember coming across that.

Robinson

He said Iran is a parasitic wasp, the United States is a lion, Hamas is a spider.

Smith

That is just so stupid.

Robinson

That's obviously an extreme example. But that guy's probably the most distinguished Middle East correspondent in the country. I think he sort of apologized for it afterward, after he got a ton of letters saying he really shouldn't do this. Now, Friedman has lived in the Middle East. He does regard the people there as human beings. So the fact that he could lapse so easily into that kind of language...

Smith

Yes, that's crucial. It really is crucial.

Robinson

I think your work is an essential caution, and so I appreciate that you write so much about this. Just to conclude here: You mentioned the future and the climate change era. Where do you think this could lead? Tell us more about that.

Smith

Well, everything I have to say is just very obvious, really. Climate change will inevitably have profound social, political, and economic consequences, and that includes huge migrations of people from the unlivable to the livable, or attempted migrations. Because, of course, we can anticipate nations will close their doors. And in that sort of chaos—we already see with migrants. The dehumanization of migrants is extraordinarily common. Well, you ain't seen nothing yet if the predictions come off as predicted. So, we have that. We have breakdowns of infrastructure, we have shifts of centers of political power and so on. And to my mind, that's a perfect storm for not only exterminationist atrocity, but for dehumanization, which sort of greases the wheels of exterminatist atrocity. So, we need to get ready.

Robinson

Well, to get ready, I hope as many people as possible engage with your work. There's a step one, which is noticing what is not always obvious. We need some critical thinking and some ability to not let these things pass casually into our discourse. I just read a quote from the National Conservatism Conference, and I tell you, if I read their speeches from four years ago, I don't think they would be as extreme, and if I read them for four years before that, they probably wouldn't be as extreme by yet another degree. So, there's a path.

Smith

Yes, that's right. There's a definite trajectory here, which is very concerning.

Transcript edited by Patrick Farnsworth.