The 'Capitalist Manifesto' is Manifestly Wrong

Endeavoring to play the same role for the Right that he imagines the 'Communist Manifesto' does for the Left, Johan Norberg simply repeats twenty-year-old libertarian errors from his previous book.

Conservatives have a reputation for hating progressive ideas like multiculturalism, socialism, and pacifism despite knowing little about them. American socialists have shared a few laughs in recent years over the right wing’s increasingly feverish books and tweets on the huge influence supposedly wielded by “race Marxism” or “postmodern neoMarxism.” Reading these, it quickly becomes clear that the Right isn’t diving too deeply into the ideas it denounces. Sometimes, their foolishness reaches ridiculous heights, like Jordan Peterson showing up to a debate on Marxism and being openly surprised to learn about some of Marx’s most basic ideas.

But the enduring appeal of left-wing ideas keeps bringing reactionaries back to the well of book writing in order to disparage the Left, thus delivering into our hands Johan Norberg’s book The Capitalist Manifesto. Endeavoring to play the same role for the Right that he imagines the Communist Manifesto does for the Left, Norberg uses his book to make arguments that will be familiar to readers of previous libertarian books, although with some special obnoxious features. But none of the predictable, chronic shortcomings of libertarian thinkers are improved upon here, such as their acceptance of the power of the ruling class and the destruction of the climate.

Old wine, new bottles. My point is, drink wine if you read this book.

Cato's Sword

Norberg is a Swede writer of libertarian politics (or “classical liberal” as they annoyingly say) and the writer and host of a number of documentaries that have appeared on American public television, including the 2014 Economic Freedom in Action and the 2017 Work & Happiness: The Human Cost of Welfare. The proud PBS legacy of airing meritless libertarian propaganda carries on, from its origins in Milton Friedman’s own 1980 Free to Choose series.

Norberg is more than a little resentful of his country’s association with some of the greatest successes of democratic socialism, including millions of units of public housing, a public pensions system, and a stupendous network of civil society groups and labor unions. He claims the country has been forced to finally discard much of its social welfare and other public programs and, misquoting Margaret Thatcher, repeats the famous claim that “sooner or later you always run out of other people’s money.” Of course, this is hardly representative of the Swedish public sector, which had great success until the wave of global neoliberalism cut it back through means like shifting the cost of services from the central government to local jurisdictions and a recent turn toward policy focused on rejecting migrants. Its surviving welfare state remains truly enviable from the point of view of a working American, but naturally Norberg’s point extends far broader than Sweden’s majestic lands. The whole world, in his view, cries out for austerity.

In addition to making relatively conventional arguments for trade and economic growth, Norberg is especially concerned that opposition to free trade deals and globalization is now a position claimed by the political Right as well as his more familiar left-wing opponents from past decades.

Thus Norberg opens his book with the lament, “What happened to Reagan and Thatcher?” A peculiar question.

U.S. President Ronald Reagan and U.K. Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher were, of course, the most recognized figures leading the great conservative turn in national and world policy now known as neoliberalism, which was a program of deregulation, privatization, tax relief for rich households, social conservatism, and aggressive military intervention. Neoliberalism was then continued by conservative regimes under Bill Clinton and Tony Blair (each under nominally progressive political parties, the Democrats and Labour), during which time most of the seeds of today’s chaos were laid: deregulating banks and finance, cutting taxes on the rich to create an even richer elite, perennially refusing to do anything substantive about climate change, letting corporations globalize, and declaring open season on unions. These leaders created the modern world.

Norberg asks the strange question because of the current resurgence of political threats to free markets and free trade, the policies his book advocates for. Bernie Sanders winning state after state in the 2020 Democratic primary? Kids supporting socialism by name? TV fascist Donald Trump utterly consuming the Republican Party and turning its partially libertarian program into one of aggressive protectionism? Whatever became of our great free ideals? Norberg asks.

So, what did happen to Reagan and Thatcher? They won. They utterly transformed society, wrenching it away from the orders of the New Deal and social democracy, which, for all their problems and limitations, had led to an actual sharing of economic growth, far fewer financial crises, and a far greater proportion of workers in unions, creating labor strength to at least partially offset corporate power. Today, our wealth inequality levels again approach those of the Gilded Age.

These leaders saw to it that companies became drastically less regulated than during the last century, and their existing regulation was largely written by their corporate legislative lobbyists to reinforce their own market dominance. Their global reach, and the role of the new tech sector in tracking and commodifying our every thought, allows the market even more control over what governments and individuals can do.

Their victories continue in the realm of climate, with major economies having taken quite limited serious action on the environment, which appears too little, too late. Many environmental goals were achieved in the developed world, like environmental policy to clean up the domestic air and water. But in the developing world, all natural systems are objects for plunder to feed global supply chains, from the palm oil in your chips that was grown on increasingly deforested Indonesian islands to the iPhone’s cobalt mined in the Congo.

And so far, the Right’s victory endures, with Sanders and his U.K. counterpart Jeremy Corbyn having been defeated in no small part by nonstop smears from the political establishment and wall-to-wall media hostility. And Trump’s administration (or his first one, anyway) was scattershot with trade policy. He started many clumsy trade conflicts which were later relatively easily wound down (except, of course, with China). One of Norberg’s big preoccupations in the book is that this tendency to be skeptical of, or antagonistic toward, world trade comes increasingly from the Right today rather than the Left.

So you won: congratulations, mission accomplished. The world sucks except for the rich. Quit whining that the increasing beshittedness of the world is causing left-wing and now right-wing backlash.

Norberg ought to know better. He’s now a fellow at CATO, the prominent libertarian think tank founded in 1977 by the prominent libertarian billionaire industrialist Charles Koch. Norberg’s cozy position only exists thanks to the massive “fiscal relief” (aka tax cuts) brought to high-income families like the Kochs, who may have been torn apart as a family by their wealth but who have major influence in spreading right-wing economics. Other beneficiaries of their tremendous wealth, like George Mason University libertarian economist and stunning boob Tyler Cowen, have been previously reviewed in this fine magazine.

Norberg says early in the book that capitalism—in other words, markets and private property—“threaten[s] the powerful.” Pretty laughable! He occupies an intellectual post that was created from concentrated capital, the thing that makes capitalists powerful in society rather than just rich. Wealth is turned into ideas people will hear when Koch Foundation-approved intellectuals get hired to teach at universities, get their books bulk-purchased by right-wing think tanks, or appear on news networks owned by other billionaires.

Norberg is doubtless sincere in his love of what he conceives as free markets and the quite real benefits of economic growth and development. It’s because of his sincerity and communicative skills that he can prepare a superficially appealing book like this, and on that basis, figures with gigantic fortunes and political axes to grind will select persons like him for their think tanks. But his legacy is of a piece with libertarians broadly, acting as a support for that part of the conservative project that upholds economic hierarchies in the workplace, in society, and certainly in the marketplace.

Norberg, Cowen, and other minions of the Koch brothers may speak and publish in the language of freedom and liberty, but their paychecks are signed by the same oligarchs that their ideas helped raise to power. Far from “threatening the powerful,” Norberg and his colleagues work for them, reaping the rewards that the owning class can bestow, like wealth, prestige, and media reach. The powerful are threatened by these “classical liberals” about as much as a king is threatened by his scribe.

Manifesto Destiny

Norberg writes early in the book, “Free market capitalism is not really about capital, it is about handing control of the economy from the top to billions of independent consumers, entrepreneurs and workers, and allowing them to make their own decisions about what they think will improve their lives.” On these grounds, he condemns socialists and their Medicare for All as well as Trumpy conservatives who want to re-onshore manufacturing: “careless talk about ‘taking control of capitalism’ actually means that governments take control of citizens.”

A bold claim to open with. Capitalism allegedly takes control from the top and subverts hierarchies, even though both eras of deregulated capitalism were ruled by tiny cliques of billionaires, whether Rockefeller, Carnegie, Morgan, and Frick in the past or Bezos, Gates, Trump, and Musk today. Norberg’s argument paints a familiar conservative picture of capitalism, where the term “free markets” signifies an imagined world where gigantic established firms magically don’t have commonly-observed market advantages, like economies of scale or network effects.

But Norberg’s main blind spot is the perennial conservative one—resistance to thinking about the concentration of economic resources and outright refusal to contemplate its ramifications. Getting anything done in society, in the public or private sector, takes resources. Changing how goods are produced by major companies or implementing public policy to alter where people live and how they get to work takes resources. It takes material goods, organizational work, and people to make it happen, and all of this must be paid for. It takes money, or capital, as we say in economics, and money is now nearly as concentrated as it was in the original, unregulated, free-market Gilded Age of the 19th century.

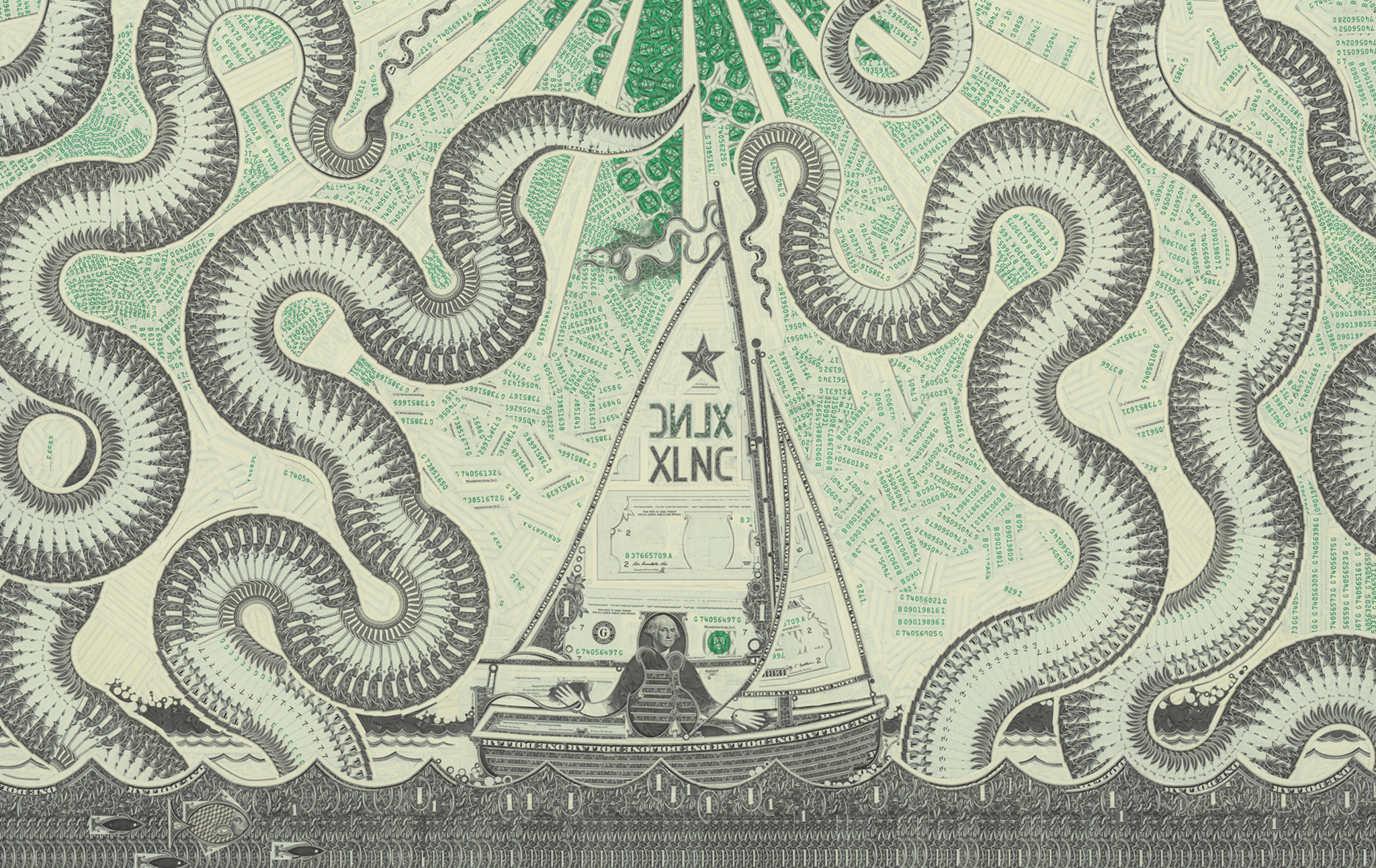

Art by Mark Wagner

Art by Mark Wagner

“Free enterprise is not primarily about efficiency or optimal use of resources. It is about opening the dams for human creativity—to let everyone participate and test their ideas and see if they work,” says Norberg. Libertarians frequently make this point, as when Yaron Brook, head of the Ayn Rand Institute, said in his debate with me that capitalism allows for experimentation since free markets and enterprise don’t keep new competitors out. Unless, of course, enterprise requires resources! “Everyone,” in this scenario, is somehow able to just get a bank loan and access capital, an idea that really stretches the imagination, especially if you have any familiarity with the realities of wealth concentration today.

The reality is that in the United States, the leading experts at the World Inequality Database estimate that the richest 1 percent of households owns 34.9 percent of all national wealth in the U.S., while the bottom 50 percent holds a whopping 1.5 percent. Meanwhile, the Federal Reserve’s Distributional Financial Accounts shows the richest 1 percent owning a similar 30.4 percent percent of all wealth and the top 10 percent owning 67 percent, as of 2024. This drastically lopsided wealth share makes a mockery of the idea that capitalism takes power “from the top.” Plainly, to the contrary, it adds to the power of the top. That’s why claims that free markets allow anyone to try out ideas don’t hold up—capital is concentrated, it’s necessary to do any large project, and banks don’t hand out loans unless you present a plausible capitalist business model (plus they want your house for collateral).

Like other libertarians, Norberg is a major exponent of economic growth and is eager to wave away concerns that all this great economic growth actually only benefits a small upper crust. He mocks economists who want “pro-poor” growth or “inclusive growth,” saying “the best way to create inclusive growth is to increase growth for everyone and to keep it up.” Perhaps, but the relatively uncontroversial numbers on growth are insane. The WID estimates that from 1980 to 2017, the 1 percent globally soaked up fully 37 percent of the world’s per capita wealth growth. The bottom 50 percent captured just 2 percent of all economic growth from the 1990s to today. In the U.S., the same research shows that the bottom 50 percent of households saw their income share fall from “more than 20% in 1980 to 13% in 2016.” So those lower incomes did grow a little in buying power, but this was in the context of an elite whose wealth has seen them grow into towering giants. These numbers unavoidably mean that when Norberg says capitalism means “growth for everyone,” he doesn’t really mean it, since he only refers to how much wealth is growing overall and just insists that this “overall” growth is for “everyone,” which is visibly not the case when the data is examined.

If most growth goes to the most affluent families and their corporate property, then it’s not the Left—but Norberg and his ilk—dooming the poor to penury. Norberg can continue to blame the Left for limiting growth and thus development, but a more credible suspect would be the overfed elite gorging on the new wealth produced by society. This is important, as growth itself comes at a cost to the planet we still live on.

Pennies from Heaven

Coping with the naked reality of the destruction of the natural environment is a perennial weak point for many “classical liberals,” and Norberg is no exception. However, Norberg is less dumb than some of his colleagues and avoids, for example, the pitfall of citing the prominent climate skeptic and international scientific laughing stock Bjørn Lomborg, cited favorably in Norberg’s first book. Lomborg is famous for his book The Skeptical Environmentalist, which argues that environmental problems like the extinction crisis are trumped-up fantasies that don’t justify the implementation of costly regulations on a capitalist economy.

Among scientists, Lomborg’s name is synonymous with irresponsible data handling and a belief in fully debunked climate myths. He later did a very public U-turn on climate specifically and called for gigantic investments in climate adaptation. Figures like Norberg, who wish to be taken seriously, have to recognize the projected economic realities and stupendous, unpayable costs of climate change and related ecological issues. The scope of these developments is well beyond the wee reformist measures he proposes (below) to grudgingly address “global warming.”

But Norberg’s treatment of the environment is a laugh and a half. He says his complete omission of climate change from his first book—quite standard practice for the Right in the ’90s—was a “startling oversight. […] I underestimated the risk of greenhouse gases.” But before you give him credit for his candor, he continues that this was “in part because so many of the environmental movement’s warnings had previously turned out to be exaggerated or outright false.” In classic conservative manner, every half-remembered environmental cause is smooshed together without citation, so that it’s our own environmentalists’ fault that poor conservatives were fooled into not taking seriously something that already conflicted with their worldviews. Note that this is based on bashing the environmental movement, not on the scientific consensus among actual climate and Earth science researchers, which was already quite sturdy in the 1990s, when Norberg was apparently too busy laughing at overpopulation fears to take thousands of professional scientists seriously.

Norberg condemns (yes, this is a quote) “the widespread perception that we cannot rely on the growth and technology that have created the problems to solve them.” His argument is that our fossil fuel-based energy system and extractive model for consuming ever-growing amounts of limited natural resources got us into this mess, and it’ll get us out. A near-universal conservative move is to refer to past fears of environmental problems not panning out. But almost without exception these are more popular media-based than scientific, usually based on half-remembered concerns they stopped hearing about and thus assumed weren’t real, even though some are still going on (like resource depletion and groundwater exhaustion), while others were actually addressed (like the hole in the ozone layer). This practice allows Norberg to carry on the right-wing tradition of utterly, abjectly failing to engage seriously with the very broad and established scientific climate literature. This is pretty pitiful, as it’s primarily a scientific issue, but keeping an ill-defined “movement” as your opponent is far less intimidating to a cowardly “social scientist” like Norberg than telling the world’s climate experts that they don’t know what they’re talking about.

Norberg settles on a split-the-difference climate solution of greenhouse emissions permits, a technocratic program popular among liberals in which emitters must buy permits to burn fossil fuels, which creates a market for pollution rights. Like many intellectual compromises, this really fails to satisfy. Climate taxes or emissions-permit systems leave extensive influence to the fossil fuel industry over the amount and assessment method of the taxes, or the amount of permits to be issued, which is one reason why emissions taxes are seen as a relatively weak climate policy by many environmentalists. This combination of weak efficacy to reduce emissions, plus implacable opposition by industry to any climate measure—meaning, any legislation would likely fail to pass in the face of this opposition—was why Exxon Mobil’s own lobbyists admitted they favored this (doomed) climate policy. On the other hand, emissions taxes are taxes, and to conservatives, Taxation Is Slavery, and no self-respecting libertarian, I mean Shmlassical Shmliberal, would ever accept such an awful statist coercion of innocent victimized power plant operators.

Norberg elsewhere admits that “Unfortunately, growth has also been an effective way of exploiting nature, but […] richer countries are also better at reducing and repairing environmental damage once they decide that is a priority.” This is an increasingly common libertarian argument today, faced as they are with a public increasingly convinced of climate change as its impacts cause fires and/or floods in their states. Since growth creates so much wealth, some of it can later be put toward “repairing” ecological devastation, Norberg says.

Norberg elsewhere admits that “Unfortunately, growth has also been an effective way of exploiting nature, but […] richer countries are also better at reducing and repairing environmental damage once they decide that is a priority.” This is an increasingly common libertarian argument today, faced as they are with a public increasingly convinced of climate change as its impacts cause fires and/or floods in their states. Since growth creates so much wealth, some of it can later be put toward “repairing” ecological devastation, Norberg says.

To which I can only say: Extinction, noun: The death of the final specimen of a species.

There is no “investment” that can restore the Tasmanian tiger or the passenger pigeon, no new “priority” that can restore to life the beautiful golden toad or the gigantic Polynesian moa, or the great ecological systems they inhabited and evolved to rely upon. Idiots like Norberg, along with fellow libertarian academic Tyler Cowen, are so consumed by the magical power of compounded growth to create alleged shared prosperity, but they generally have zero scientific credentials. They’re resultantly quite happy to make hideously blasé remarks about how future growth will create new science for “reducing and repairing environmental damage,” presumably resurrecting long-vanished ecosystems or doing a Jurassic Park to bring back some dodos for their grandkids to view.

This truly disgraceful glibness cannot survive any familiarity with today’s global extinction wave, where mostly human economy-driven extinctions are running at 100 times the normal background level and up to 1,000 for some genera. Scientists routinely refer to this as the “Sixth Extinction”—meaning it’s the sixth known global event in the full history of the world—or as the Anthropocene extinction, since it’s recognized to be a direct result of our wonderful economic growth. Norberg also considers 21st-century poverty reduction under capitalism to be “the greatest thing that has ever happened to mankind.” A great stride for humanity indeed, and yet the worst thing for almost all other forms of life on Earth.

Norberg’s treatment of the environment is disgracefully irresponsible and charmlessly blasé, but of course it’s all part of his larger body of work.

In Offense of Global Capitalism

While reading Norberg’s book, I realized another work of his has been sitting on my office shelf for some years, his In Defense of Global Capitalism from 2001, published in the U.S. in 2003 by CATO. This book, making familiar liberal arguments for growth and trade, was fun to revisit because of the timing of its release, immediately prior to the calamities of the 2000s, including global terrorism and a several-trillion-dollar world financial crash. This puts some of its recommendations in not precisely the most flattering of lights.

Writing after a resurgence of skepticism of capitalism after the 1999 Seattle anti-WTO protests, Norberg declaims, “In the anti-globalists’ worldview, multinational corporations are leading the race to the bottom. By moving to developing countries and taking advantage of poor people and lax regulations, they are making money hand over fist and forcing other governments to adopt ever less restrictive policies.”

Yes. The naked fact that giant trillion-dollar companies are incredibly mobile and can shift operations to poor states granting the most solicitous tax and regulatory “relief” gives them the upper hand throughout decades of globalization. But Norberg gives the game away as he laments that “The fact that 51 out of the world’s 100 biggest economies are corporations is repeated like an ominous mantra. […] Big corporations are no problem—they can achieve important economies of scale—as long as they are exposed to the threat of competition. […] What we have to fear is not size but monopoly.”

So, we’re told that we dumb leftists fear giant companies just for being giant, but in fact it’s monopoly that’s the problem. But that’s just it—the neoliberal era built by Norberg’s peers and favorite political leaders has seen wall-to-wall deregulation of industry, and—big surprise!—it’s been followed by a tsunami of consolidation, from chemicals to banking to railroads to airlines to media to energy to beer to insurance to cell carriers. It’s just a naked undeniable fact that Norberg’s precious deregulation has in fact led to near-universal oligopoly, and frequent full-on monopoly, in industry after industry and sector after sector. Giant firms, especially international ones, have incredible market power in oligopoly markets, and anyone denying this is just embarrassing themselves.

Looking back at the regionally cataclysmic (but today often-forgotten) East Asian financial crisis of the late 1990s, he insists, “Countries should liberalize their domestic financial markets. [...] Supervision and regulation […] have to be reformed, and competition must be permitted.” But deregulation of finance and competition among banks led directly to the stunning wave of mergers and consolidation that eventuated in the “megabanks,” the too-big-to-fail monsters whose failure would plunge the economy into chaos and contraction. Libertarians cannot bear the idea that competition frequently begets oligopoly, captured when the great socialist author George Orwell said in his review of Friedrich Hayek’s book Road to Serfdom that “The trouble with competitions is that somebody wins them. Professor Hayek denies that free capitalism necessarily leads to monopoly, but in practice that is where it has led.” Orwell called the resulting rule by monopolistic capitalists “tyranny.”

So it’s not “What we have to fear is not size but monopoly.” Just so happens you get size and monopoly with deregulation. Norberg is quite right that big companies exploit major efficiencies that any socialist society would definitely want to preserve, above all economies of scale, in which very large-scale operations lower costs enough so that essential goods remain widely available and relatively affordable. That’s an argument for size, and for socialism, since private companies with these efficiencies are extremely large and powerful, sufficiently so to both strong-arm society and to frequently flee anywhere, well-proven in the 20 years since this little ghoul of a book was published.

So it’s not “What we have to fear is not size but monopoly.” Just so happens you get size and monopoly with deregulation. Norberg is quite right that big companies exploit major efficiencies that any socialist society would definitely want to preserve, above all economies of scale, in which very large-scale operations lower costs enough so that essential goods remain widely available and relatively affordable. That’s an argument for size, and for socialism, since private companies with these efficiencies are extremely large and powerful, sufficiently so to both strong-arm society and to frequently flee anywhere, well-proven in the 20 years since this little ghoul of a book was published.

And yet, Norberg smugly implies, as all these jacked-up simpleton servants of capital do, that monopoly mainly arises from state policy. Feudalism and mercantilism being far in the past, today’s monopoly arises more frequently from simple market forces like scale economies and network effects than it does from direct government favor, as Orwell observed.

Norberg’s older text is a great time capsule of ’90s-era libertarian thought, advocating policies that led to roller coasters of disaster in the new century. For a defense, it helped eventuate some grave calamity indeed.

Go Swede Racer

One distinguishing feature of Norberg’s libertarianism is a particular emphasis on pandering to liberals. He seems to stroke his chin as he writes:

There’s a reason why it’s so pathetic when some on the left claim that capitalism is racist and racism is capitalist. On the contrary, the market economy is the first economic system that makes it profitable to be colour-blind and look for the best supply and the best demand, regardless of who is responsible for it. Of course, it will not make everyone colour-blind, but it does so more than otherwise would have been the case (especially in combination with the liberal values on which capitalism is based).

Quite! After all, who ever heard of redlining, the once-common banking practice of denying mortgages to African Americans, who in the U.S. are of course historically poorer and therefore considered by lenders to be credit risks? (Redlining may have officially ended in 1968, but banks like Wells Fargo carried on their own discriminatory tradition by pushing higher-priced subprime loans onto Black and Hispanic people as recently as the 2010s.) What about the ubiquitous segregated lunch counters of the Jim Crow South? Libertarians love to—again, glibly—conjecture that because racist policies like those will hurt a business (since, in this reasoning, all the Black customers and whites of conscience will go elsewhere), they will not persist. “Segregation would alienate consumers,” Norberg claims. The inverse sounds more plausible—the customer market itself is racist, and local businesses (being often operated by similarly racist persons themselves) will naturally cater to the far-larger white market by barring African American customers, on straight free market grounds.

How are markets supposed to integrate (or make color-blind) institutions that serve racist markets? Since Black people in the U.S. are a smaller population and have lower average household wealth than whites, what can we expect from profit-seeking companies other than to cater to the main market? Tech firms have spent the last several years falling over themselves to sell identity-tracking software to the FBI and cops to better monitor Black people (with some reduction after the George Floyd murder). Who the hell sold all those Black people to U.S. and Brazilian slaveholders, anyway? After letting half of them die on the hellish passage over, that is. It would be the great merchants and traders of the era, of course. What a pandering phony.

Notably, before his insistence that it’s “pathetic” to suggest capitalism has made its contributions to racism, Norberg elsewhere mocks how concrete goals of economic growth and freedom are being replaced by “fuzzy code words such as inclusivity, sustainability.” It’s economic growth that will save all you restless minorities, not your leftist political demands for resources! With these vague and somewhat condescending gestures toward inclusion, only to return once again to enforcement of property rights that benefit the rich, Norberg isn’t doing a very convincing progressive pantomime here.

Norberg doesn’t benefit by comparison with the almost charmingly shallow charlatanry of other Koch-funded libertarians like Tyler Cowen, whose books Nathan Robinson and I reviewed somewhat slightly unfavorably. Cowen’s “Monopoly doesn’t matter because you can scroll Facebook whenever you want,” or even the weird frozen-in-time canards of Ayn Rand-genre libertarians, are preferable to this. The pandering to multiculturalism and racial equality, claiming “the market economy is the first economic system that makes it profitable to be colour-blind,” gets pretty nauseating as Norberg writes off any problems posed by economic inequality, such as billionaires who buy newspapers and TV networks with pocket change.

He concludes the book warning the reader to be wary of “authoritarian revolts” that could disrupt the Panglossian capitalist utopia, which of course to him means putting a wealth tax on the Koch brothers to pay for Medicare for All. Norberg’s books stink. I prefer other Swedish exports, like social democracy and ABBA, to this.

This book is stacked cover to cover with rehearsed libertarian talking points, dancing around the same gigantic blind spots and weaknesses, rich with pandering to shallow liberals and selling the same warmed-over, weak-sauce, right-wing goose shit from so, so many other libertarian classics. A manifesto you can detesto.