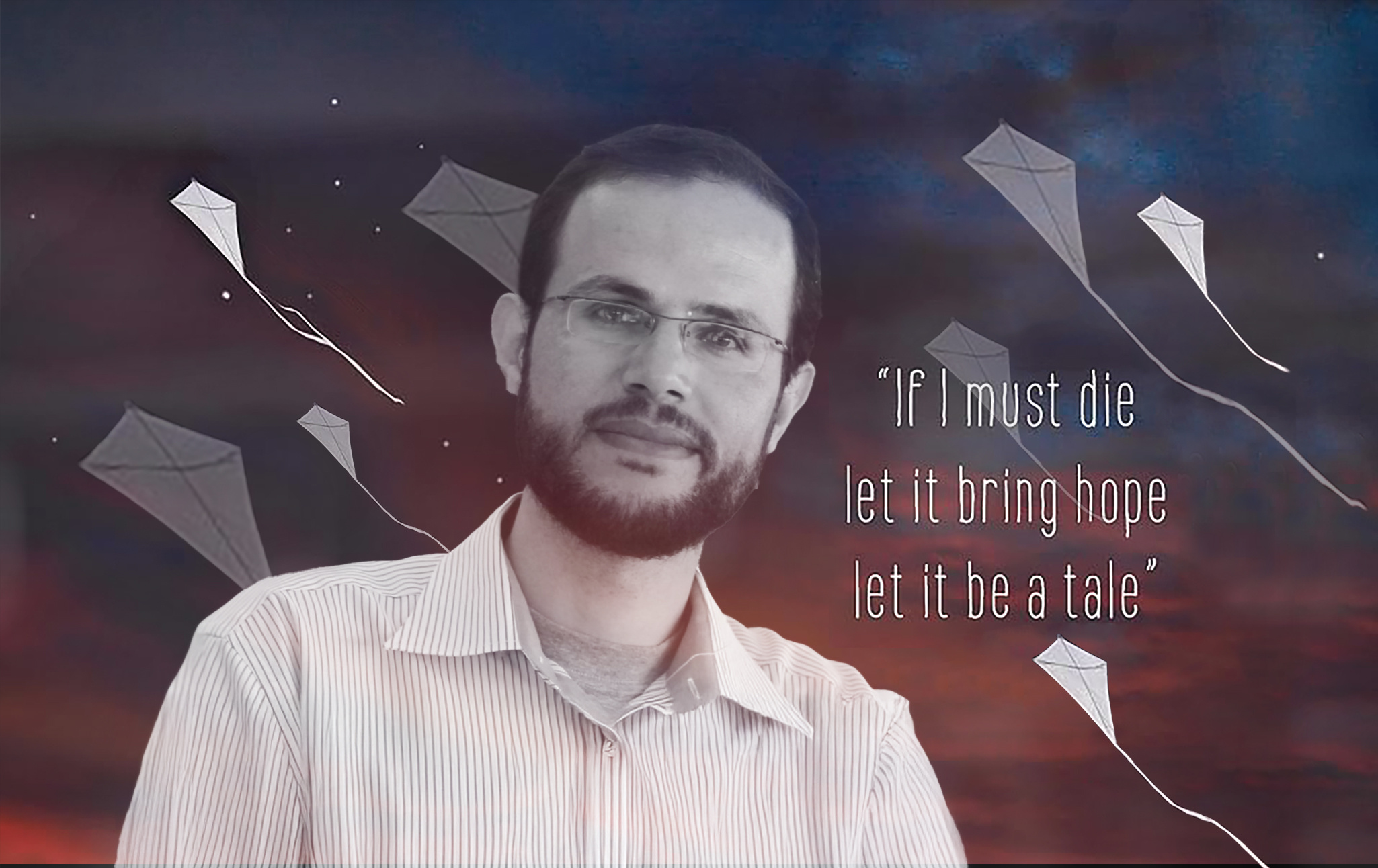

Refaat Alareer's White Kite Will Fly Forever

A year ago, Israel murdered a poet, scholar, and activist for the human rights of Palestinians. Now, a new book ensures his message will live on.

Last Friday, December 6, marked one year since the murder of Dr. Refaat Alareer by the State of Israel (and by extension its accomplice, the United States). Alareer was one of the most important literary voices of Palestine—a poet, essayist, and professor of English literature whose work has changed the lives of countless people, both in Gaza and far beyond. His life was brutally cut short by an Israeli airstrike, which Euro-Med Human Rights Monitor describes as “surgical” and “apparently deliberate,” targeting his sister’s apartment “out of the entire building where it’s located.” It was the second time Alareer had been the target of Israeli bombs, after he and his family survived a strike on their own home in late October 2023, and it came after weeks of death threats from Israeli soldiers and their supporters over his online activism—threats spurred on by Free Press editor Bari Weiss, who painted a target on Alareer’s back on social media. Writing after that first airstrike, Alareer speculated that his home had been singled out because he was sharing electricity and other scarce resources with his neighbors, “helping people to live a ‘normal’ life despite Israel's attempts to starve us,” or perhaps “because I talk to the media.” But if the Israeli military and its hangers-on hoped that they could silence Alareer’s voice or put a stop to his activism by taking his life, they severely miscalculated. They may have killed the poet in physical form, but his message lives on, and one year later, it’s stronger and clearer than ever.

Since Alareer’s death, his poem “If I Must Die” has become one of the most widely read of the 21st century. It’s been translated into more than 70 languages, including Chinese, Spanish, Hebrew, Greek, Russian, and Hindi, and has been viewed more than 33 million times on social media. It’s been carried on handmade signs through street protests, recited by renowned Shakespearian actors like Brian Cox, and graffitied on walls from Ireland to Atlanta. On the slight chance you haven’t seen it yet, it goes like this:

If I must die,

you must live

to tell my story

to sell my things

to buy a piece of cloth

and some strings,

(make it white with a long tail)

so that a child, somewhere in Gaza

while looking heaven in the eye

awaiting his dad who left in a blaze–

and bid no one farewell

not even to his flesh

not even to himself–

sees the kite, my kite you made, flying up above

and thinks for a moment an angel is there

bringing back love

If I must die

let it bring hope

let it be a tale.

Perfect poems are rare, but this is one. Even critics hostile to Alareer’s politics and art, like Tablet magazine’s Maxim Shrayer, have to admit they find it moving. If Alareer had written nothing else, his place in literary history would be assured by “If I Must Die” alone. But as it happens, he wrote and edited quite a lot besides that one famous poem. There’s his 2014 book Gaza Writes Back, in which he collected the short stories of his literature students and introduced a new generation of Palestinian writers to the world. It’s now available in a memorial edition that provides updates on where each contributor is today—those who could be contacted, that is. And this week, O/R Books has published a collected edition of Alareer’s writing, curated by his former student Yousef M. Aljamal and entitled If I Must Die: Poetry and Prose. In its pages, we can find a richer and more detailed portrait of a teacher and writer who was taken from the world far too soon.

Reading If I Must Die, the first thing you notice is that Alareer saw his death coming a long way off. In fact, the titular poem was not written during the current assault on Gaza, although you might get that impression from the way it’s been described in the press as “the last poem shared by Alareer.” Shared, but not created. In fact, it was written all the way back in 2011, when Alareer was only 32 years old—and when he had already begun to see his loved ones hurt and killed by the Israeli state. This is a crucial thing to realize, because it serves as a counter to the narrative that the current bloodshed began on October 7, 2023, with the Hamas attacks on Israel. On the contrary, long before that day, much of the Alareer family tree had already been cut down. In an essay called “They Even Keep Our Corpses,” Alareer writes poignantly of his uncle Oun, who was arrested and tortured to death by the IDF in 1971, and whose son Yasser was later arrested in turn by a soldier who taunted him, telling him that “I killed your father.” In “Israel’s Killer Bureaucracy,” he tells us about the life and death of Awad Alareer, his cousin, who died of cancer after Israeli officials insisted on endless security checks that delayed his treatment until it was too late. In the same essay, he notes the passing of Awad’s uncle Tayseer Alareer, a farmer who was shot on his own land by IDF soldiers in 2001. He gives us “The Story of My Brother, Martyr Mohammed Alareer,” who was killed by an Israeli bomb at the age of 31. He even recalls how his father was badly injured in 1985 by a hail of bullets that came out of nowhere from an Israeli gun and struck his Peugeot car and how he feared riding “shotgun” ever since. No wonder, after seeing all that, that he could write a poem like “If I Must Die”—or even “O, Earth,” from 2012, in which he pleads with the ground to “devour me / To suffer no more.” For him, an early death was always more likely than not.

Almost every piece of writing in the book is to some extent an elegy, and Alareer describes war and death as a member of the family—“a grumpy old relative, one that we can’t stand but can’t rid ourselves of either.” In an essay from 2021, he says of himself and his wife that “Nusayba and I are a perfectly average Palestinian couple; between us we have lost more than thirty relatives.” By late October 2023, the number had increased to “over fifty.” (Nor, for that matter, was Alareer himself the last to die, as his daughter Shymaa was killed by yet another airstrike this April.) In this way, the Alareers are indeed “perfectly average,” as Israel has annihilated every member of at least 902 different Palestinian families—further evidence, if you needed it, of the genocidal nature of its so-called “defense.” It’s an old cliché that “a single death is a tragedy, [but] a million deaths are a statistic,” but the news coverage of Gaza can often feel that way; when you see a headline like “Death toll in Gaza from Israel-Hamas war passes 44,000,” the scale of the devastation is so huge that it’s hard to grasp in human terms, like the distance between the Earth and the Sun. Alareer brings us back down to the individual level, and shows us the tragedy that we in the United States are indirectly responsible for.

It’s a strange experience, reading If I Must Die on the cusp of the American holiday season, when your own family is making plans to hold reunion dinners free from starvation or the threat of sudden death. It’s a reminder of how fragile and temporary human life really is, and it brings with it a strong sense of guilt about sitting and reading comfortably at home while people in Gaza can’t do the same. And yet the book is also deeply touching. Knowing that their lives could be snuffed out at any moment, Alareer did his best to immortalize the people he cared about most in poetry, complete with all the idiosyncratic details of their histories and personalities. The best example of this comes in “Over the Wall,” a remembrance of his grandmother:

‘There,’ points Grandma.

She had a tent that was a home.

She had a goat and a camel.

She had a rake and a fork and a trowel.

She had a machete and a watering can.

She had a grove and two hundred plants.

She had a child and another one and another one.

‘There,’ she insists.

I could not see

Because of the wall.

I could not hear

Because of the noise.

I could not smell

Because of the powder.

But I can always tell,

I am sure of Grandma

Who always was

And is still

And will always be.

This is unmistakably a political poem. It makes a pointed critique of the Israeli apartheid wall that separates Gaza from the rest of the world, the violence that’s needed to enforce that separation, and the historic theft of Palestinians’ farms and homes during the Nakba. But in preserving the memory of his grandmother in the written word, where bullets and explosions can’t touch her, Alareer also offers something else: a grandson’s simple act of love.

Indeed, despite the book’s often gloomy and death-laden subject matter, love is a constant theme in If I Must Die. Beyond his own family, Alareer also shows a strong sense of devotion to his students, who he seems to view as family themselves. In the essay “Gaza Asks: When Shall This Pass?,” he writes that in the aftermath of Operation Cast Lead—another of the many Israeli onslaughts, this one in 2008 and early 2009—“I decided that if I lived, I would dedicate much of my life to telling the stories of Palestine, empowering Palestinian narratives, and nurturing younger voices,” training young Gazans to tell their stories in English for the wider world to read. Again, this is a political project. The ability to read and write well in the lingua franca of the time has always been a potent tool, which is why enslavers in the United States forbade the enslaved to become literate, and why “Each One, Teach One” has been a slogan for revolutionary movements around the world. Alareer taught a lot more than one, and in the preface to If I Must Die, Yousef Aljamal—who was one of his students—describes him as trying to raise “an army of young writers and bloggers able to challenge Israel’s narrative on Palestine.” But this was more than politics; it was also evidence of a great faith in his students’ abilities, and a desire for them to have a future that was brighter than the life Alareer had lived himself. Aljamal writes that Alareer was “loved deeply by his students,” and that the “adoration was mutual, as Refaat cared for his students like his own children,” and an influence like that won’t soon be forgotten.

In turn, this goes a long way toward explaining why Israel saw fit to assassinate Alareer. The United Nations has identified a “pattern of attacks on schools, universities, teachers, and students” in Gaza, where Alareer was just one of the “5,479 students, 261 teachers and 95 university professors” who had been killed as of April 18. This constitutes the crime of scholasticide, and its motive is obvious. As James Baldwin wrote of the United States, “The victim who is able to articulate the situation of the victim has ceased to be a victim: he or she has become a threat.” Israel, like all oppressor states, badly wants to prevent such threats to its dominance from emerging. Like the English kings who occupied Ireland for centuries, it uses the destruction and suppression of the occupied culture to cement its rule. And so eloquent and outspoken Palestinians like Refaat Alareer are marked for death from the moment they put pen to paper.

The love of art and culture for their own sake, too, is unmistakable in If I Must Die. Like Edward Said, his predecessor in the fields of Palestinian literature and politics, Alareer believed in “cultural universalism”—the idea that great artistic works can be appreciated by anyone, without regard for the nation or ethnicity of the writer or reader. Alareer’s writing is rich with references to both Palestinian writers and the classics of the English-speaking world, blended together equally, just as his teaching aimed to help people on both sides of the cultural divide understand each other better. In one poem, he borrows a line from Macbeth to write that “‘All the perfumes of Arabia will not’ / grace the rot / Israel breeds” when it kills; in another, he makes a joke about Oliver Goldsmith’s 1773 play “She Stoops to Conquer.” One of his earliest pieces of published writing is an extended riff on Jonathan Swift’s A Modest Proposal, and his doctoral thesis was on John Donne—a sixteenth-century poet only the nerdiest of English majors in this country still read with much enthusiasm—but who was Alareer’s favorite. In his lectures, which are still available on YouTube, he taught Wilfred Owen, Laurence Sterne, T.S. Eliot, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, and a dozen others. What’s more, he taught both male and female students equally—a fact that would be nigh-incomprehensible to the Western writers who like to portray all of the Middle East as a sexist backwater, and use women’s rights as an excuse for imperial war. He even had moments where he sounded like an exasperated American feminist, recalling in the essay “An Introduction to Poetry” how he had to correct his class about the poet Fadwa Tuqan: “Please don’t introduce her as ‘Ibrahim Tuqan’s sister.”

What’s ironic is that, for all that English-speaking conservatives like to drone on about the importance of the so-called Western Canon of literature, Alareer understood its treasures a lot better than the majority of them. Like Said, who should have been free to write poetry as he once did in his youth, Alareer, with his talents and love of the written word, should have had the peace and quiet he needed to write a really excellent book on Donne. It’s a great injustice that he was forced to wade into the tawdry world of geopolitics and spend so much of his time writing about death and destruction. The fact that Alareer was deprived of the opportunity to more fully express his creativity is hardly the greatest injustice in Gaza, but it still stings.

Alareer even had a surprising degree of compassion—if not exactly affection—for his oppressors in Israel. In the poem “I Am You,” he addresses Israelis directly, appealing to their moral conscience and trying to spark a sense of shared humanity in the reader:

I do not hate you.

I want to help you stop hating

And killing me.

I tell you:

The noise of your machine gun

Renders you deaf

The smell of the powder

Beats that of my blood.

The sparks disfigure

My facial expressions.

Would you stop shooting?

For a moment?

Would you?

All you have to do

Is close your eyes

(Seeing these days

Blinds our hearts.)

Close your eyes, tightly

So that you can see

In your mind’s eye.

Then look into the mirror.

One. Two.

I am you.

I am your past.

And killing me,

You kill you.

This mirrors exactly the case made by members of the Israeli antiwar movement, such as journalist Gideon Levy. Levy says that the “Killing of Gaza” (the title of his recent book) is not just bad for Gaza, which is obvious, but bad for Israel, too, as its society has become “brainwashed” by fear and hatred to think of all Palestinians as mortal enemies. In If I Must Die, Alareer tries to break down that hatred, even writing at one point that “Sometimes I think we may one day find it in our hearts to forgive Israeli leaders” once their occupation of Gaza ends. He also rejects antisemitism explicitly, speaking fondly of the “generous Jewish hosts” who gave him a place to stay during a book tour in the United States. He promises to teach his daughter Shymaa that the struggle for Palestinian liberation is political in nature and not religious:

I will tell her that we were made to believe the fight is between Jews and Palestinian Christians and Muslims. And I will tell her Israel builds walls and checkpoints to maintain this fiction and to keep us isolated. I will tell her that in my tour I learned that Jews, too, can and have been victims, and that Judaism has been hijacked by Zionism.

In another essay, Alareer recalls teaching his students The Merchant of Venice, and slowly helping them to overcome their initial lack of sympathy for Shakespeare’s Jewish characters:

I worked very closely with my students to overcome all prejudices when judging people, or at least when analyzing literary texts. Shylock, therefore, also evolved from a simplistic idea of a Jew who just wanted a pound of flesh to satisfy some cannibalistic primitive desires of revenge into a totally different human being. Shylock was just like us Palestinians. [...]

Perhaps the most emotional moment in my six-year teaching career in [the Islamic University of Gaza’s] English department was when I asked my students which character they identified with more: Othello, with his Arab origins, or Shylock the Jew. Most students felt they were closer to Shylock and more sympathetic to him than Othello. Only then did I realize that I had managed to help my students grow and shatter the prejudices they had grown up with because of the occupation and the siege.

For his trouble, Israel bombed Alareer’s university soon afterward, claiming it was a “weapons distribution center.” All of his notes on the Shakespeare module—which he’d planned to turn into a book—were lost, depriving the world of another fascinating academic work. Later, the same daughter he’d taught religious tolerance was the one killed in this April’s bombing. The phrase “no good deed goes unpunished” springs to mind.

In the months since his death, there has been a concerted effort to ignore these facts, and to portray Alareer as virulently antisemitic. It’s unfortunate that this even has to be mentioned in a review of his book, but the narrative is a persistent one, and needs to be addressed. In his Tablet profile of Alareer, Maxim Shrayer writes that “poets of Gaza are voices of Israel-hatred by choice, and channels of antisemitism by default,” and said that he would “love to see some evidence to suggest otherwise.” In a more crass statement, the often-ridiculous organization “StopAntisemitism” went so far as to call Alareer “an antisemitic monster, nothing more” on the anniversary of his death. (The “nothing more” is especially offensive, as even if you believe Alareer did harbor some kind of antisemitic views, he was clearly other things besides.) The basis for this charge, to the extent there is any, comes from two incidents: one when Alareer tweeted an edgy joke about the rumor that Hamas baked children in ovens on October 7, asking if it was “with or without baking powder?,” and one when he described certain Israeli poems—most notably by Tuvia Ruebner—as “dangerous” and said that “this kind of poetry is in part to blame for the ethnic cleansing and destruction of Palestine.” Just on the face of it, that’s pretty thin stuff to justify accusing someone of being an “antisemitic monster,” but the label falls apart even further when you look into either incident. In the first case, there was never any real evidence that anyone, young or old, had been baked in an oven on October 7; in fact, when reporters from Ha’aretz and the ultra-Orthodox website Kikar Hashabbat asked IDF officials and volunteer rescue workers in the area where the baking supposedly occurred, they all said they “were not familiar with the incident.” To this day, there is still no solid evidence for the alleged atrocity, although Hamas committed plenty of real atrocities, which are bad enough without inventing new ones. So it seems Alareer had a point when he dismissed the “ovens” story as absurd war propaganda. Undoubtedly, his joke was in bad taste—but people who are actively being bombed in their homes are, I think, entitled to a little bad taste from time to time.

Meanwhile, the claim about Alareer being antisemitic because he disliked certain Israeli poems is even more nonsensical. When you actually zoom in to the (heavily edited) lecture video that was used to smear him as a “hatemonger,” one of the Tuvia Ruebner poems in question reads as follows:

THERE, I SAID

I set out from my temporary home to

Show my sons the place that I came From

“There,” I said. “I lay on the ground

With a stone for a pillow, lower than the grass,

Like the dust of the Earth;

Everything has been preserved There.”

Notice what’s being said here? The speaker sets out from a “temporary home” to a “place that I came From,” a clear allegory for moving from Europe to Palestine—something Ruebner actually did in 1941, fleeing Nazi Germany. The place he dubs “There” is described as consisting of stones, grass, and dust, “preserved” as if for the speaker’s use, with no people. This can easily be read as a depiction of the colonial myth that Palestine was “empty” before the 1947 Nakba, a “land without a people for a people without a land,” which the Israeli scholar Ilan Pappe has brilliantly debunked in his book Ten Myths About Israel. You can disagree with Alareer’s judgment that the poem is “dangerous,” and you can have a debate about it; that’s what literary journals are for. But the fact remains that “empty land” narratives like the one Ruebner’s poem arguably depicts have contributed to denying and excusing the violence of the Nakba, just as Alareer said. At any rate, to dismiss him as simply a raving antisemite is ludicrous, especially when you consider it in context with Alareer’s diligent work against antisemitism in the classroom. It’s a politically-motivated attack, and a contemptible attempt to kick dirt on the name of someone who’s no longer around to defend himself.

Israel has murdered Refaat Alareer, and the world is poorer without him in it. But in their attempt to silence him, they have accidentally done the opposite, and spread his words to more people than ever before. Even without a single book written (rather than edited) under his name, he’s become the Palestinian equivalent of someone like Chinua Achebe or even Shakespeare himself, whose works are synonymous with the history, culture, and struggles of his homeland. Now, thanks to the work of Yousef. Aljamal and O/R Books, he has a book, and it’s a fine one. Alareer will live on in his poems and essays, and people will still be reading his work when Benjamin Netanyahu, “Genocide Joe” Biden, and the rest of the soldiers and politicians who took his life are nothing but a bad memory. He will live on in his students, like Ahmed Sbaih, Wesam Abo Marq, Amnah Shabana, Mahmoud Alyazji, Hend Ghazi Alfarra, Sahar Qeshta, and Sara Nabil Hegy, all of whom have written moving memorials for him and will doubtless go on to teach and inspire others in turn. He will live on in projects like the Refaat Alareer Mobile Library, a mutual aid program that provides books to people who can’t otherwise afford them in Atlanta, in the Refaat Alareer Camp that’s currently providing medical care in Gaza itself, and in We Are Not Numbers, the nonprofit he helped found to pair young Palestinian writers with mentors who can help them master their art. And he will live on in every person who reads his words and finds themself moved to speak up against genocide, and to work for the liberation of Palestine and its people. His kites are flying everywhere now, more and more of them by the day, and the whole world can see.