How America Imagines a 'World of Enemies'

Osamah Khalil on how, both domestically and abroad, American elites have conjured existential nemeses who must be dealt with through never-ending militarization.

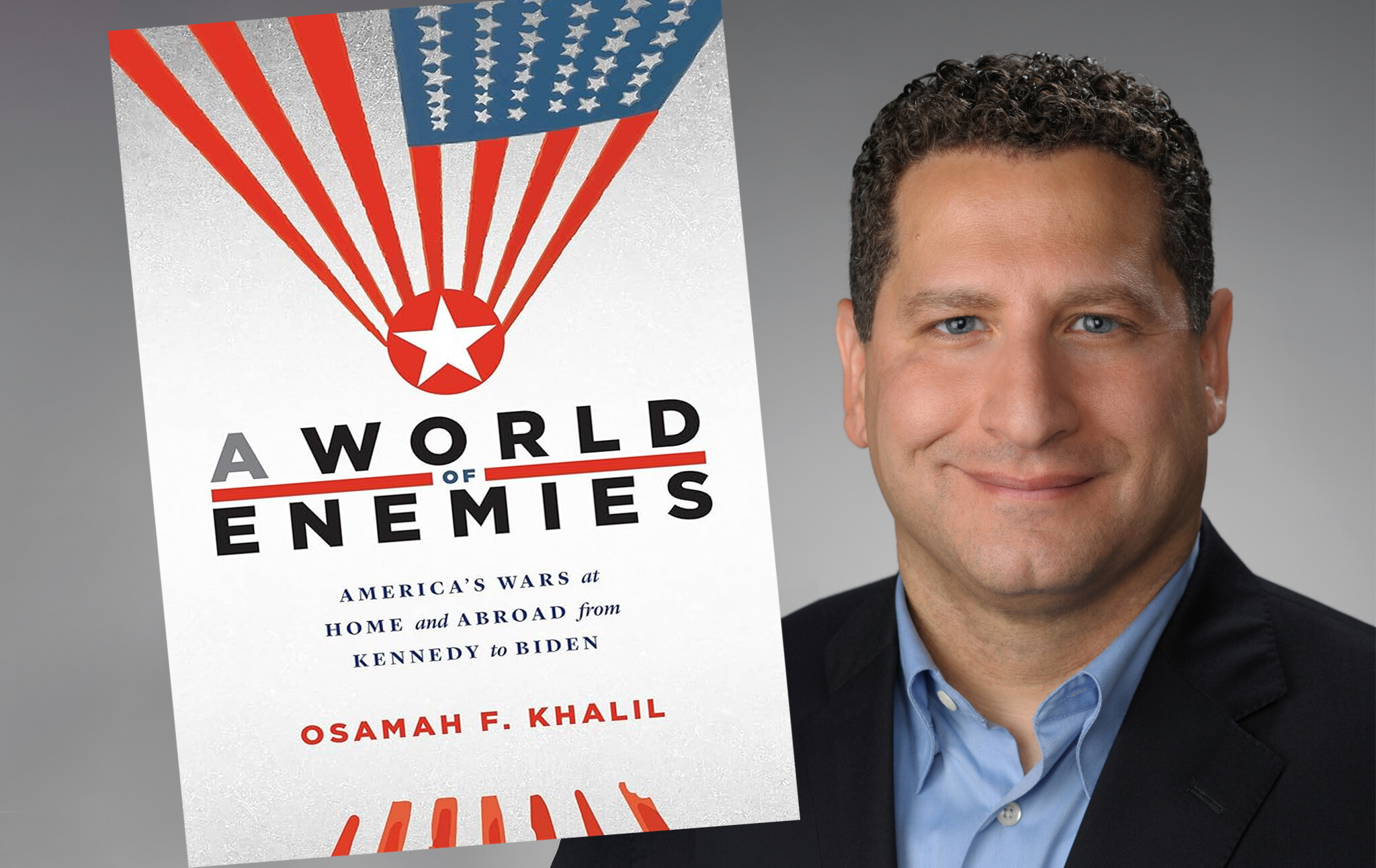

Osamah Khalil of Syracuse University is the author of A World of Enemies: America’s Wars at Home and Abroad from Kennedy to Biden, a vital history of the wars of the last 50 years. Prof. Khalil shows how, from the Vietnam War to the present day, American leaders (and American pop culture) conjured a "world of enemies" in which force was preferable to diplomacy. A cast of rotating villains (from Ho Chi Minh to Saddam Hussein to Hamas) are treated as existential threats to freedom and democracy, and because they are monstrous, they cannot be negotiated with and can only be destroyed. Prof. Khalil joins today to discuss his work, which argues that our militaristic attitude toward the rest of the world has also come to characterize domestic political discourse.

Nathan J. Robinson

You do something a little unusual in this book, which is hinted at in the subtitle. We are used to thinking about America's wars abroad and America's wars at home separately, in different domains. We talk about the history, from Vietnam to Afghanistan and Iraq, or we might talk about the war on drugs, but you put it all together and see it as one kind of unified history, domestic and foreign. Tell us why you think we need to consider America's wars as one category that includes domestic and foreign.

Osamah Khalil

We tend to think of these as two distinct and separate spheres: the domestic sphere and the foreign policy sphere. What I wanted to get across was how much domestic politics and policy not only influenced foreign policy but how foreign policy has come home and influenced our own domestic politics and policy. And so I wanted to trace that out from the Vietnam War era to the present. One of the challenges was, where do you begin this story? I could have started in 1945, but what really struck me about these intersections between the wars on crime, drugs, and terror was how influential that period was, particularly with the baby boomers.

If you think about the United States in 1945, or even in 1959, the idea that American power was unbounded, the American dream would be fulfilled for generations to come, that this was the American century, so much of that is embodied in Kennedy's inauguration speech. And as I talk about in the book, you have a whole generation of baby boomers who come into government service, whether it's State Department, Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), Department of Defense (DoD), or even running for elected office, they were inspired by Kennedy, and Vietnam became their testing ground. And then on top of that, I argue in the book that America's failure in Vietnam has profound consequences, not just for the policies the United States pursues at home and abroad, but also for how it views its place in the world and these perceptions of decline, and the continuing ramifications of those perceptions of decline take us from Kennedy to Reagan to the Bush years and then, of course, eventually, the Trump presidency.

Robinson

You point out how the shadow of Vietnam hangs over everything that comes after it and looms large in the story that you tell. As time goes on, the Vietnam War fades into history, and Americans probably know less and less about it. I hear statements sometimes made that I think perhaps wouldn't have been made 20 years ago. I'm thinking of John Fetterman, who said it was a war to defend democracy. That was something people believed in 1965, but I thought we'd gotten past that. So you encourage us to go back and understand what the Vietnam War was and why it mattered. Tell us a little bit more.

Khalil

It's a great point you're making and one I've seen with my own students. In part, this book was written for this younger generation that is getting very little history of the Vietnam War in high school or college. Unless they take a specific class in college, they're unlikely to get it. The Vietnam War has had these profound implications, not just for how the United States views its place in the world—the idea that this will be this great testing ground, to your point—but for how it's talked about at home as defending democracy. And then, of course, one of the great revelations for many of the baby boomers is that South Vietnam was not a democracy, that this was an insurgency and not a civil war. It was presented in certain ways. The way the Kennedy, and then Johnson and Nixon administrations, in some respects, would talk about it as an invasion from the north. And so to see this as a homegrown insurgency against, initially, a dictatorship funded and supported by the United States, and then a military junta, is one issue.

The second issue is, as the war was failing and the United States was throwing immense resources at, again, this very poor, what we then called third-world nation, and not demonstrating an ability to defeat this insurgency, the United States sought to contain the impact globally. Domestically, there was a second problem, which is that it now coincided with rising internal dissent, and so we started to see a number of aspects at home in dealing with this issue, including domestic surveillance that's connected to foreign surveillance. We're seeing attempts to “contain” radicalism, whether student protesters, the Black Power movement, or even the movement for civil rights. And that had profound implications for the Johnson and the Nixon administration and then beyond.

And then the third piece is, again, as the Vietnam War effectively ends, this idea that the American Dream is no longer achievable begins to be adopted, and actually, Nixon ran a bit on this. So this actually formed Nixon's campaign, in addition to things like law and order very much tied to crime, drugs, and, of course, urban unrest, and law and order abroad. And that's going to, again, be about containing the impact of Vietnam.

So there's the other aspect here that is really important for your listeners and readers to understand: there are policies that are implemented in Vietnam—counterinsurgency policies—that are also applied domestically in the United States and then exported as well to different conflict zones. They will be revisited, as I talk about in the book, again and again, in different conflict zones, and much like Fetterman's quote that you began with, instead of actually looking at their failures in Vietnam, they will be presented as successes. So everything from key counterinsurgency aspects that we will revisit with the global war on terror, that will then be presented as well. These were successes in Vietnam, and we're going to apply it here in Iraq, Afghanistan, or elsewhere, and that includes everything from torture to full-on assassination programs. The connection to, as I talk about in the book, the attempts now to infuse a ton of money into Afghanistan and develop Afghanistan, in a sense, on the Vietnam experience, and like in Vietnam, it fails.

Robinson

About a year ago, we interviewed Vietnam veteran Bill Ehrhart, who has written some great memoirs of the war. He said on this program that when he went to Vietnam—having seen all the Audie Murphy movies about World War Two—he thought he was going to be welcomed with open arms. He thought the women were going to throw flowers at him because he understood America through the lens of the great, heroic World War Two stories. And when he got there, it was a profoundly disorienting experience that he was unable to process until years afterward because he couldn't understand why he was hated. He couldn't understand what he was doing there. He said, nothing made sense. And then he realized it was this horrendous atrocity, and his image of the country just collapsed completely. But it was very difficult for him to accept that the United States he had believed so much in could, in fact, be doing what you laid out there. And what you said there I wanted to dwell on because you said that it wasn't a civil war, and I think people will say, no, it was a civil war. No, it wasn't a civil war. There was no North and South Vietnam. These were artificial entities. So there's so much about that war that even the people who were in it had struggled to understand.

Khalil

Whether it was the Kennedy and then, of course, the Johnson administration, they would not even talk about it from that perspective. This was an invasion. One of the things they would constantly talk about was infiltration from the north, which there was, but that there was also a strong domestic base of support in South Vietnam for the insurgency opposed to the government of Ngo Dinh Diem and then the juntas that come in afterward. The other thing I would throw out, even if you begin to talk about it as a civil war, as you start to see later, it was a civil war within South Vietnam, not so much between these two countries. And that is, of course, a leap. It won't be until, for example, the Nixon administration, that we finally saw an American President talk about recognizing the National Liberation Front (NLF), what the Americans called the Viet Cong—the VC—and recognizing them as a political actor. And of course, this is a fundamental piece of what North Vietnam wants, what the NLF wants, but the Americans refuse to recognize or deal with the NLF. I think the other thing that's really important there, and you've tapped right into it, is a number of Vietnam veterans have talked about this—Ron Kovic, for example—which is the influence of John Wayne and Audie Murphy and the influence of those World War Two movies.

One of the other aspects that is important, and is a thread that runs through the book, is the idea of the quick victory. Of course, for the Johnson administration, they expected this to be a quick victory. How could it not? The world's most powerful military was going to go fight against, quite frankly, as they would refer to it, pajama clad fighters with sandals and AK-47s. How could they stand up to us? And so, one of the things I get across in the book is not just the arrogance that persists through conflicts over the next six decades, including, for example, in Yemen today, but how when this desire for the quick victory with use of overwhelming force to achieve it doesn't happen, the decision is not made to back off. The decision is now made to increase force. And so, for example, one of the things I hope readers and listeners will take away from this is the following: in 1964-65, as President Johnson is deliberately preparing for war—he’s lying to the American public as he's going into the '64 campaign and preparing for war right after the election, and the idea here is to dictate terms of surrender to North Vietnam. So you have a military strategy that's connected to a political strategy in which, quite frankly, they will literally say they will make North Vietnam beg for peace through this bombing campaign. So this was never about meeting as equals at the negotiating table. We're going to dictate surrender, and we will see that again and again in different conflicts.

As I talk about in the book, think about 2003, when President Bush gives Saddam Hussein 48 hours to withdraw, take his sons, and leave Iraq, or military action will commence. Or, quite frankly, in December 2023 when Secretary of State Blinken, right after the humanitarian pause ended and there was an exchange of Israeli hostages for Palestinian prisoners, said, all this could be over tomorrow if Hamas just surrendered. You still have this over and over again, this really quite persistent belief from the United States that it can dictate terms of surrender, and when that doesn't happen, as I talk about in the book, that reinforces notions of decline.

Robinson

Of course, in Afghanistan as well, the Taliban offered to surrender. I think Rumsfeld said, we don't negotiate surrenders in this country. And the Taliban were even offering to give up Osama bin Laden at that point.

Khalil

Exactly. I talk about another key moment with Afghanistan. For example, in 2008, feelers were put out for negotiation for a power-sharing agreement, much like the United States had just done in Iraq under the Bush administration, and this was rejected. It's rejected wholesale by Condoleezza Rice. And, in fact, much of what could have been achieved, perhaps, with that power-sharing agreement would have avoided another almost decade of war, with the eventual victory of the Taliban. And so that could have been avoided as well. Of course, some of this is well-documented. Some is documented in the book. And there's still more that we'll learn about, all these missed roads and opportunities that were not taken because, quite frankly, the administrations of power knew better or had another agenda, as in the case with Rumsfeld.

Robinson

There's obviously an arrogance of power there with the belief that you don't need to make compromises because you can just inflict absolute defeat. But there are a few kinds of racism: the racism of believing in the weakness and stupidity of your enemy, the racism of believing that you face an implacable foe who can't negotiate because they are ruthless and merciless—they are enemies. And you saw this kind of contradiction as early as the war against Japan during World War Two, where the Japanese were both weak, foolish children, and superhuman. Tell us about the way the conception of the enemy plays into this.

Khalil

It's a great point. So yes, the dastardly villains—the evil Japanese who are, on the one hand, like innocent children that had to be molded, and on the other, would stab you in the back. And I think that's a persistent thread I talk about in the book. There's a broader framework of the war for civilization. You're seeing some of that play out again today. How the United States talks about its enemies is often a reflection of how it talks about itself. We are civilized, they are savage. And we see that in the use of phrases like Indian Country, for example. The U.S. military still applies some of this phrasing and terminology that it used in its own genocidal wars in the American West against Native American tribes into the 20th and 21st century. So that war for civilization rhetoric is really profound, and it's consistent.

The other thing that ties the wars on crime, drugs and terror together is that all three have been presented as these wars for civilization. Crime is drugs, and then, of course, the war on terror, and then built within that is what happens to these areas that, as I talk about in the book, what the United States begins to refer to as Badlands. The Badlands is this really rich metaphor, as you can imagine, for policymakers. You can take what were areas that were laden with “crime” at the turn of the century around the prohibition era—taking that myth from the American West, of the Badlands and these areas of Native American violence to be subdued, to America's inner cities for crime, then by the '90s for drugs, and then, of course, it's adapted into the global war on terror logic. The Badlands are applied to Afghanistan and Pakistan, Gaza, Somalia, Yemen and so forth. And they actually come back home by the late Bush administration with Mexico's war on drugs because the Southwest United States is now a Badlands. And so much of this becomes really rich territory, and it taps into this cavalcade, this rogues' gallery of evildoers. So whether it is El Chapo, Saddam Hussein, or Bin Laden, Americans are often presented with this rogues' gallery of enemies, much like with Ho Chi Minh, that can't be negotiated or reasoned with. All we can do is fight them, and we must fight until the bitter end. And sadly, what it has led to is a foreign policy that's fully militarized. We don't even think about diplomacy anymore. We're almost always initially relying on military force.

Robinson

And because of that view, obvious opportunities for diplomatic resolution of conflicts are missed. Obviously, Hamas is now the most prominent example. People talk about Hamas the way they talked about the Taliban and al-Qaeda after 9/11. They're pure evil. They can't be reasoned with. You just have to destroy them. And we miss the various kinds of diplomatic feelers that were put out by Hamas for many years, where they indicated maybe they'd be open to a two-state settlement. Because we already know who these people are, we deal with them accordingly.

By adopting that perspective, in many ways you create the threat that you think exists. You have this striking thing that you mentioned in the book, where you say that only a fraction of the dollars that were spent in the global war on terror were actually needed to secure the homeland, so we ended up spending a lot of money to increase the threats. Can you talk about how adopting this view actually makes the threats that we perceive worse and more real?

Khalil

Absolutely, and it's a great point. It's often missed. I just had this conversation recently, where we've just passed another 9/11 anniversary, and what's striking is how the younger generation, either born on or since 9/11, knows so little about that day and what happened and who was involved and even just some of the basic facts about it. And for example, as I talk about in the book, what's missed often in this discussion is that it was 19 hijackers armed with box cutters. They weren't agents of a superpower. They weren't even agents of another state actor. And, in fact, much of this could have been avoided with locks on cabin doors. Al-Qaeda, as most Americans refer to it, had likely fewer than 1,000 members, maybe even fewer than 100, and yet, the Bush administration completely blows this out of proportion. And of course, it's for political reasons, as well as the shock and awe of the day.

But in terms of conflating a number of groups with al-Qaeda, so tying in Hezbollah, Hamas, and Palestinian Islamic Jihad, along with a number of other groups in and around South Asia, and claiming these are global terrorist organizations that are either a threat to the United States or its allies and partners in the region and across the world—that's one fundamental mistake. Even today, 20-plus years later, we've settled for security theater at airports. I don't think anybody feels safer. We know, for example, based on the audits of the TSA, that it's not a well-functioning organization. Anybody who's been through an airport knows that. We know that they fail audits regularly. We also know that less than three percent of cargo that comes into the United States is ever searched. So there's where we've diverted our money.

And so, of course, there's the war and occupation of Afghanistan for 20 years in which the United States, even as its allies, particularly Afghan President Hamid Karzai, talked about bringing the Taliban into the government and finding a way to split this movement. This movement had several different aspects to it that could have been divided and played against. Instead, the United States decided we will not do that.

And then, of course, the war in Iraq, which we often now just refer to as a blunder. And what that does is to paper over how much of a criminal act this was in terms of deliberate deception of the American public, of the international public, the drive for war and the way the war is conducted, and the occupation that occurred and the number of lives lost, which we still don't know, and the profound implications for Iraqi society and the broader region. All of this comes with a cost. It comes with a cost both at home and abroad for Americans, not just in our standing in the world, but the fact that we are still conducting military operations in and around Iraq is telling about where we are 20-plus years later.

To bring us back to domestic politics, much of that history has been forgotten. You've seen it with the embrace, for example, of Vice President Dick Cheney, one of the architects of the war, by Kamala Harris. You've seen it when you look at some of the key architects and proponents of the war, how they have now fully embraced the Democratic Party and want more of this kind of policy, not just in the region, but globally. Even when President Biden announced that he was not going to stay in the race, he claimed he was proud to be the only American president to not have soldiers at war. And yet, the United States is active in several different war zones, including in Iraq. And so this has had profound implications, not just for our society, but how we think about what it means to be at war. And that's one of the things I want, hopefully, your listeners and readers to take away. What are the trade-offs to pursuing this kind of policy, to pursue endless war for decades without even thinking about what it means for the families that are involved? And quite frankly, Nathan, we never think about the populations overseas. They're invisible.

Robinson

You mentioned al-Qaeda, a core group of about 1,000 people that could have been dealt with accordingly. With the global War on Terror that was launched after 9/11, the Brown University Costs of War Project has tried to estimate the human toll of these wars, and Americans really don't understand the amount of direct and indirect consequences—the cascading consequences. They ultimately have concluded that as a result of the wars that were spawned in the post-9/11 era, the human toll approaching a million direct deaths, with another three and a half million indirect deaths, and 38 million people displaced by the post-9/11 wars in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iraq, Syria, Libya, Yemen, Somalia and the Philippines. It's the greatest displacement of human beings since World War Two, and essentially undiscussed in the United States.

Khalil

No, we don't discuss this at all. And to give one example of it, think about how little discussion there was of Afghanistan, perhaps from Obama's second term, up to the peace agreement that was signed during the Trump administration. This was rarely discussed in the press, particularly as it was failing. Number one, you had very few media based in Afghanistan, and that was from the Bush period on. So there was not much media attention. When there was media, it was mostly focused on a particular military exercise, and often what you would hear was that the U.S. military went into Helmand Province, they engaged with some Taliban fighters, but the Taliban fled, only to reemerge a month or two later or three months later, and reoccupy these areas without ever understanding, why did they have so much support, especially in the rural areas versus the urban areas? So we've done a poor job, I think.

And it's easy to blame the media, but the reality is that Americans haven't been paying attention. Part of that has to do with the fact that we have a volunteer military. We no longer have a draft. This is one of the key differences between the Vietnam era I talked about in the book. You have a volunteer military, in which the footprint of those that are affected is small. The other aspect is that war has become deeply embedded in our economy and dual use. Whether it's from technology companies or your old standard military contractors, it's deeply embedded in a way that is often invisible to most Americans, and yet they benefit from it. You've had a recent example of this, quite frankly, earlier in the year, where the Wall Street Journal and President Biden, who agree on almost nothing—the one thing they agreed on is that foreign military assistance benefits comes back home in the form of American jobs. So when the Wall Street Journal is saying almost the same thing as President Biden, that should actually strike us. And that, I think, is quite telling.

In that Brown study that you referenced, one of the things that they point out is the cost of this—the human cost and the financial cost. If the wars continue, which they have, those costs keep compounding. The other thing is we're still dealing with a full generation of men and women who fought in these conflict and the wounds they sustained. The rehabilitation, the mental impact—all of this is going to last for decades, and the costs of that, both human and financial, is one that we have yet to even fully understand or engage with.

We're seeing it, quite frankly, today in and around the Red Sea. There was some recent reporting, for example, by the Associated Press, which talked to some of the sailors who were deployed. And one of these talked about how this is the first major naval engagement that the United States has had since the Second World War and how stressful it was to actually be under fire every day, multiple times a day. And this is to keep in mind by, the de facto government of Yemen, which only a decade ago was a non-state actor but now has very low-cost drones and missiles that the United States is countering by spending millions of dollars to shoot down—millions and effectively billions of dollars by the time we're done. And what the Houthi militia and the Ansarallah movement have shown is that they can actually trade tit for tat with the strongest navy in the world and its air force and can cut the trade and traffic through the Red Sea in the Suez Canal dramatically—there are some estimates that it's more than 50 percent or even higher the amount of trade that's been impacted in and out of the Red Sea. And no discernible benefit to U.S. military action. None.

So U.S. air strikes against the Houthi militia have not deterred them. You have the bombing of schools, most recently by U.S. air strikes, that have not deterred the Houthis. The book was published before October 7, but there was this moment that really sums up the book and its argument back in January, where the United States begins these airstrikes against Yemen and President Biden is asked, are the airstrikes working? He says, are the airstrikes working? Do you mean, are they deterring the Houthis? No. Will they continue? Yes. And this fundamentally sums up U.S. foreign policy.

Robinson

U.S. foreign policy in a 10-second nutshell: Is it working? No. Will it continue? Yes.

Khalil

If I had known, I would have held off on the book, Nathan. I just would have waited if I had known he was going to do that. So just wait three months, we'll have this. And what's sad is that it has continued and just bring us up to where we are. U.S. air strikes have not deterred the Houthis, nor has the United States been willing to end Israel's invasion of Gaza, which it is not only fully supporting but participating in. Now, the Houthis have made it clear, if you get a ceasefire in Gaza, we will end the interdiction of shipping. The Biden administration has sought to separate these two, and it has said, the Gaza war is contained. It's kind of your typical, there's nothing to see here folks, move along. There's nothing happening in Lebanon. There's nothing happening in Yemen. These are separate.

At the same time, they know they're directly related. And what we're seeing is, in typical fashion, op-eds being written, including one recently by a leading professor and someone at the American Enterprise Institute (AEI)—AEI is a think tank, and the war in Iraq was basically shaped at AEI—in which he's arguing that right now, the United States is losing the war in the Red Sea, and he says that the issue here is that Biden's not going to do anything, and this is an issue for the next president. And so this, again, takes us back to the argument of the book. So what's the wrong lesson that's going to be applied? He's saying is that the United States actually needs now to amplify its actions in and around Yemen—

Robinson

More force.

Khalil

More force because we're sending the wrong message to China. We are weak now. Our standing in the world is weak. And what is the message China will get if we can't stand up to the Houthis in Yemen? What does that say about Taiwan and the Taiwan Straits? One of the key things I talk about in the book is policy that's actually a failure being discussed as a success. And so a great example of that is to go back to Colombia in the 1990s, in which you have this idea of dictating terms of surrender. The Clinton administration was faced with a fairly thorny negotiation between the FARC, this left-wing rebel group, and the Colombian government. And so instead of actually really engaging in diplomacy, we're going to launch a counter narcotics effort that's really counterinsurgency, and the way it's pitched at home is this: we will eliminate Colombian cocaine from American streets in three years. Okay, so clearly, if that's the initial goal, we know that failed. And instead, what ends up happening is we have a massive infusion of force into Colombia that leads to broad human rights violations, the highest death rate in the world for three or four years.

We shifted from a counter narcotics campaign after 9/11 to a counterinsurgency counterterrorism campaign. But here's what's remarkable: the same ambassador who's put in charge in Colombia by the Bush administration will be told, you did such an amazing job in Colombia with your crop eradication, go now to Afghanistan and do the same thing in Afghanistan. So we're going to take a failed policy in Colombia—obviously we didn't eradicate cocaine in Colombia—and we're going to take it to Afghanistan, where it will also fail, and at the same time, claim these were both successes. So it's a remarkable statement about U.S. foreign policy, and not only how it's militarized, but also how it's portrayed as a success when, in fact, it's a failure.

Robinson

The response to losing is that we clearly need more bombs and more force, which inevitably every Wall Street Journal op-ed is about. What's the problem in Ukraine? The problem is clearly we need more force. How do we solve the problem with Iran? Well, clearly, we just need to increase our threats—we're not credible in our threats. Well, what's the problem in Gaza? Israel is not being given enough destructive force.

Khalil

They're fighting with one hand tied behind their back. I make this point in the book: not everybody who went to Vietnam obviously drew the same lessons from it. And I think it's important to remember the lack of education about what happened in Vietnam today. The same way that there's a lot of really strong and divisive opinions and differing opinions on the war on terror, there's also obviously still about Vietnam.

So, scholars are split on this. They're not evenly split, but you will still find a particular segment that will come and tell you that the war was winnable. If we'd only listened to X, Y or Z individual—often Edward Lansdale or someone else—we could have won that war. Max Boot has a whole book about this. But also, you will hear from military figures, including some of those that served: politicians hurt us, the hippies back on campus hurt us, the press hurt us, we were fighting with one hand tied behind our back, and that's why we lost in Vietnam. They, the “Viet Cong” quote, unquote, never defeated us on the battlefield. So that's going to become really important to some of these key figures as they stay in government service, particularly DoD and CIA, and when I talk about them, the United States tends to contain the impact of Vietnam. They will take some of these policies out into Latin America, into the Middle East, into southern Africa, to try and apply them there, with mixed results. Sometimes they're successful. Most of the time they're not.

This takes us back to your earlier question, but it's going to entrench these conflicts in a way that removes certain options. So, for example, I talk about how in the Obama administration, even though key figures were being killed with the drone assassination campaign, they're being replaced. And you're starting to get these differences within the administration, some of which plays out in the press, saying, what we're doing is killing people, but we don't really have an end game here. We don't know how this ends, or where it ends. The other thing I would bring up, and this comes back to your point, is how this plays out today in the media. In the Wall Street Journal, you'll have these op-eds that are written by two or three figures at the Atlantic Council, where it's always calls for more force. All you have to do is switch out the headline. You could switch out China and North Korea with North Korea and Russia, with Russia and China, Russia and Iran, and just keep alternating who to bomb next. There's constantly a threat the United States has to be preparing for.

And so whether it is someone at the Atlantic Council writing about foreign policy or it's the National Review or the National Interest, these journals that are tied, often, to the foreign policy establishment, and of course, military contractors are shaping this public opinion of a perpetual threat that can only be dealt with by military force.

Robinson

You write a lot in the book about pop culture and movies and the way that our policies shape the pop culture that we get, and then we imbibe it and get this view that essentially, war is like it is in movies. First off, you don't have to see the worst parts of it. You don't have to see horrible things happen to children. You just see people fall over. But also, that war consists of going out and killing the enemy, and then you win the war. And in every case that you mentioned, in these stories of the world of enemies, there's this basic fact about human beings that I feel is missing, which is that human beings react like human beings to violence. So with Israel's recent pager attack in Lebanon, with all the people who are traumatized by that, do you think they're just going to go home and not care? Or do you think they're going to be angry and resentful? Of all the people in Gaza who survive, are they not going to spend the rest of their lives despising you for this? In Afghanistan, when we were dropping bombs on villages and calling them Taliban, the people in those villages knew that you're lying, and do you think they don't despise you afterward? Do you think they don't want to get back at you like a human being would? It's crazy.

Khalil

The challenge is, as I mentioned, that we rarely ever talk about the cost. Even if you think about the great Hollywood movies about Vietnam, one of the things we miss is that there are few, if any, Vietnamese characters ever. Instead, it's all about the impact on the American soldier. The Deer Hunter does this in remarkable fashion. It's one of these movies that is the standard for this approach. The other issue is not only how pop culture influences action. So for example, and barring on the reporting and investigation, I talk a little bit about the impact of a show like 24 on using torture and interrogations, and how that is then taken to Iraq and applied to individuals who are arrested, scooped up, and tortured because the soldiers believe that they're just acting out what they've seen Kiefer Sutherland doing on the show 24. There's another aspect here, where, if you look at the press coverage, you brought up the pager attack—the exploding pagers. How it's being discussed in the media in the United States and in some cases Western Europe, is the following: look at the technological marvel. And, of course, everybody who had a pager, remarkably, was a “Hezbollah member.” Not that this is a form of communication that's still used by doctors and nurses, that we still don't know a lot about how exactly this happened, how widely available these pagers were, and what else may be exploding in Lebanon and what the implications are of it. And instead, you're hearing a narrative that the only ones who were killed were Hezbollah members, which must be quite reassuring for us as Americans. And this, of course, fits into a much broader theme.

If we go back to Vietnam, keep in mind, body counts were the key measure for the U.S. military of how they were defeating the insurgency. But this was also connected to promotion for both civilians and the military. If you go in and you're doing a search and destroy mission or a pacification mission, and you've killed 200 “VC,” that's great for the company commander, down to the soldiers. It's how you get promoted. It's how you get your R & R, how you get everything up the line, from the company commander to the general in Saigon to back in the Pentagon. Because it's a successful operation.

Well, then it turns out that they weren't 200 VC. They were individual villagers. The only way you could justify this action was because you just killed a bunch of villagers, and you've claimed that they were all VC. So then you take that and create an assassination program, the Phoenix Program, and you say, we're only going to target the “Viet Cong infrastructure.” So, Viet Cong infrastructure (VCI), as the CIA comes up with, and these amazing terms that you'll see repeated again and again. All this will sound familiar to your listeners, as you see how it's repeated in different conflict zones. The Viet Cong infrastructure—the CIA literally invents some number that's based on what they believe are the number of people who were trained, and this is how they describe it. So these are the number of Viet Minh, the original fighters who fought against the French, who go up to the north to be trained from the south and then infiltrated back. And so the idea is, there's 54,000, so if we set a goal within two years of eliminating 54,000 members of the VCI that will crack the insurgency. So, lo and behold, they institute this program, and they start within the first six months and are killing a certain number of individuals, and it looks like they're on track to kill 54,000, and then, of course, what you finally get is the revelation of, we now realize that we may not have been killing insurgents, and even if we were, it appears that our policies have actually created more than we were killing.

And you will hear this again in Iraq —this is what makes David Petraeus famous and almost a presidential candidate. David Petraeus, the famous general, actually—again, back to the Wall Street Journal—has a new piece of the Wall Street Journal about what we can do to win in Ukraine, in which he'll talk about this kind of counterinsurgency math, which is that what you want to do is adopt policies in which you are not creating as many insurgents as you kill. Whether it's the pager attack or it's the genocide in Gaza, think about this: at a minimum, we're looking at 21,000 orphans in Gaza. That's 21,000 orphans have been created in Gaza, at least a similar number of children under the age of 16 have been killed. How many new members of Hamas or another organization do you think you've created? Exactly what's the future look like when you have completely devastated this coastal territory, which was already under 17 years of siege, where 80 percent of the population are refugees, as the U.S. calculate refugees, going back to the 1948 Palestine war and the Nakba, the creation of the Palestinian refugee community? Eighty percent are refugees in one of the poorest places on Earth, and one of the most densely populated, and now it's been completely devastated. So you have that calculus.

You have the pager attacks followed by the walkie-talkie attacks followed by everything else. How many new insurgents are you creating? Is it in the fivefold and the tenfold? For example, Hezbollah has helped train a number of different militias around the region, including in Iraq and the Houthis in Yemen. And Kata'ib Hezbollah in Iraq has already said, we will help fill your ranks. We will volunteer to help fill your ranks for whoever was injured in these attacks. I want to point out one last thing. Yemen is such an interesting example because here's a case where you had the Saudis come to the Obama administration—how much this was a push and how much was a pull is, of course, up for discussion—but the Saudis argue they can defeat the Houthis in six weeks. That was a war that went on for over seven years, a war in which there were open war crimes bordering on a genocide. And the Saudis failed. And that was with full U.S. and U.K. support of the Saudi campaign—the Saudis with the United Arab Emirates, several other allies. Instead, what it did was it turned the Houthis from this ragtag militia into a battle-hardened militia that then became the de facto government—which, as I talked about earlier, is now openly challenging the strongest Navy in the world. This should tell us something about these conflicts in which they were promised a quick and decisive victory. Instead, what it turns into is a long, drawn out and ultimately bitter defeat.

Robinson

To conclude here, one of the things that struck me when I read and wrote about the Vietnam War is how there's a chain of logic that leads you to think that genocide is necessary. If you do believe that the war is over once you've killed the enemy, and your policies are turning more and more of the population into the enemy, then it's becoming more and more necessary to destroy the population itself. And of course, three million people died in the Vietnam War. It is arguably genocidal in its consequences even if we don't think of it as having the requisite intent.

And it strikes me that Israel's approach towards Palestine is very similar. When you create Palestinian resistance, you see that resistance as a sign of a threat. You have to eliminate the threat, meaning you have to eliminate the Palestinians. You create the situation in which you've made your only option genocide—if the world is enemies, you can't win until you destroy the world.

The extreme point here that you haven't mentioned is nuclear weapons—if we have this view that we face people who just need to be destroyed, they can't be reasoned with. Putin can't be reasoned with, and he has to be met with force, and we escalate in response to him. We can't back down, so we have to send the long-range missiles. He escalates. Well, then the only option is to continue escalating. This is a nuclear-armed state, but we can't back down because no negotiations are possible. It leads you to this place where you've reasoned your way into creating horrific destruction. Could you discuss the threats that this view of the world, which is entrenched in the United States, now leads us towards?

Khalil

I think it's a great point and a great question you raise. That's not only how we look at the enemies abroad but how we look at our own domestic population. That's one thing that connects these Badlands and how we think about those trade-offs about war. What aren't we spending this money on? When we look at our own domestic issues, our own inner cities and rural areas, where aren't we spending money? So much of this came together with the COVID pandemic, as I talk about at the end of the book. The fact is that the United States, with the greatest military in the world, was caught under after decades of warning about a public health infrastructure that was weak and needed huge investments of money. The fact that we responded so poorly to the COVID pandemic should itself lead us to raise questions. It has led us to more divisiveness over things like masks and vaccines when we should be asking much deeper questions about that.

On the destructive capability, we spent a lot of time on Gaza and Yemen, but you're absolutely right about Ukraine. One of the things that was so striking about Secretary of State Blinken’s initial reaction to Russia's invasion was, we're not going to negotiate with Russia until the war is over. How do you expect the war to end? What we've learned then is that the U.S., with its allies, particularly the U.K., sought to prevent any kind of negotiated settlement over the next six to nine months, including blocking one almost a month into the war. It's remarkable, particularly where we sit today. Russia actually has not been defeated on the battlefield. It hasn't been defeated by sanctions. It has tightened ties with China. And so, at some point, we need to stop thinking about this from a constant world of threat into a world of cooperation. That message has not gotten across, and it's not going to get across with this book. It doesn't seem to have gotten across, even if you think about either presidential candidate. And remarkably, somehow Trump had the less warmongering speech than Kamala Harris did in terms of their acceptances.

What's also remarkable—and I think this also ties in when we think about Blinken from Ukraine to Gaza—is that shortly after October 7, Blinken takes part in the Israeli war cabinet. And what hasn't been discussed is the following: why is the U.S. secretary of state, America's top diplomat, in the Israeli war cabinet? That's not the place for him. That's for the joint chiefs of staff. That's for the secretary of defense. That's not for the secretary of state. He should be out negotiating a ceasefire. He should be out talking about de-escalation.

And in fact, we had the opposite. We had him, by the end of that first week, sending out memos to the State Department saying that we're not gonna talk about de-escalation. We're not gonna talk about a cease fire. This should tell us something about the militarization of foreign policy. It's setting us on a path, and this is my concern, for whoever is in power. We don't know what a Trump presidency will look like. We keep hearing these warnings that he's going to be even more unhinged than he was in the first term because he has nothing to lose.

Now, that may just be this kind of idea of having to talk this way for the election. The problem is that it's never just for one election. Pretty soon we have the midterms, and from the midterms, we have re-election, and then it's about helping my successor. So to your point, we are now tangling with, and you can see this inch by inch—inch by inch is actually conservative—we are jumping well ahead in Ukraine and attempting now to continue to tangle and embed ourselves in a conflict with Russia, a nuclear armed state, without an off-ramp. And there have been several off ramps possible but not one in which we are willing to accept a “defeat” and a Russian victory, and we're seeing the same thing in Gaza. We won't accept anything but a “full defeat” of Hamas, even though we also acknowledge that that's not possible, which leads us to more and more endless conflict. And quite frankly, the implications, not just for the globe, but for the populations there, as well as for the broader globe, are really profound, and they're profound for us at home as well.

Transcript edited by Patrick Farnsworth.