Lessons from the Business Plot

In 1934, American oligarchs planned a 'Wall Street Putsch' to stop Roosevelt’s New Deal. What would today’s capitalists do if their power was under threat?

For the past three years, American politics has existed in the shadow of January 6. Since the right-wing riots at the Capitol, hardly a week has gone by without new press coverage of the congressional hearings, the ongoing criminal case against Donald Trump, and the scandals about Supreme Court justices’ alleged support for the “Stop the Steal” movement. As another election draws near, the “threat to our democracy” posed by Trump and his followers has been a central theme of the Democratic presidential campaign, and countless journalists have speculated about a possible repeat performance of January 6 if Trump loses in November. None of this should be surprising. The spectacle of over 2,000 die-hard MAGA supporters breaking into Congress, some of them wearing shirts with neo-Nazi slogans like “CAMP AUSCHWITZ” and chanting “hang Mike Pence,” was enough to rattle anyone. But if we take a look through history, 2021 was not the first time the United States faced the prospect of an antidemocratic coup. Nor, for that matter, was it the most serious. For that, we have to turn the clock back to 1934, when the country’s financial elite tried to overthrow President Franklin D. Roosevelt. By looking at the “Business Plot,” as it’s known, we can gain some valuable insight into the political threats of our own time.

In 1934, FDR was a president at the beginning of his time. His greatest achievements, like the Social Security Act and the creation of the federal minimum wage, were still ahead of him, as was the outbreak of World War II. But Roosevelt’s economic agenda had already begun to anger the wealthiest Americans, earning him powerful enemies. In his first Inaugural Address in 1933, the incoming president railed against the country’s “unscrupulous money changers,” placing the blame for the Great Depression squarely on bankers, stockbrokers, and the rich as a class:

[T]he rulers of the exchange of mankind’s goods have failed, through their own stubbornness and their own incompetence, have admitted their failure, and abdicated. Practices of the unscrupulous money changers stand indicted in the court of public opinion, rejected by the hearts and minds of men. […] The money changers have fled from their high seats in the temple of our civilization. We may now restore that temple to the ancient truths. The measure of the restoration lies in the extent to which we apply social values more noble than mere monetary profit.

For an interesting mental exercise, try to imagine Joe Biden or Kamala Harris saying anything this bold today. It’s hard. Roosevelt set big goals, demanding “a strict supervision of all banking and credits and investments” and “an end to speculation with other people’s money.” To be clear, he wasn’t a true socialist like Eugene V. Debs or Upton Sinclair, his contemporaries. Roosevelt’s “New Deal” was aimed mainly at stabilizing the capitalist system, not ending it. But he did assert that democratically elected leaders held authority over commerce and the market, not the other way around. In essence, he told Wall Street: You had your chance in the driver’s seat, and you crashed the car. Now the government takes the wheel for a while.

For the ultra-rich, who have never taken kindly to any limit on their wealth and power, this might as well have been full-blown Marxism. William Randolph Hearst, one of the most influential newspaper barons of the era, wrote in the Chicago Tribune that Roosevelt’s administration was “more Communistic than the Communists,” and the Hearst papers devoted endless column inches to tearing down the New Deal as it took shape. Other prominent capitalists, including the chemical company millionaire Irénée du Pont and General Motors CEO Alfred P. Sloan Jr., founded the American Liberty League in 1934. A precursor to modern conservative networks like the Federalist Society and the Heritage Foundation, the League trumpeted the virtues of property rights and the free market, loudly opposed the Social Security Act, and disparaged left-wing economic ideas at every turn. For both sides, the battle lines had been clearly drawn.

At the same time, one of the United States’ most fascinating historical figures was entering a new phase of life. Major General Smedley D. Butler, of the U.S. Marine Corps, had retired from the military in 1931 after 33 years of service. Butler had joined the Marines in 1898, lying about his age in order to enlist for the Spanish-American War at just 16. Over the next three decades, he became a ruthlessly effective soldier for the U.S. empire. Among other wars and military interventions, he fought in the U.S occupation of Veracruz during the Mexican Revolution, helped to put down the Boxer Rebellion in China, waged the so-called “Banana Wars” to protect U.S. fruit company interests in Central America, and invaded Haiti, where he later wrote that his men “hunted the Cacos [rebels] down like pigs.” He even served a brief stint as the head of the Philadelphia police in 1924, taking a leave of absence from the Marines, and led a violent Prohibition crackdown against bootleggers and speakeasies that included 973 police raids. By the time of his retirement, he’d been richly rewarded for shedding all that blood, and was the most decorated Marine in the corps’ history up to that point, having received both an Army and Navy Distinguished Service Medal and two Medals of Honor—the highest award the U.S. military has to offer.

Importantly, Butler had also started to clash with the federal government over politics, especially when it came to the treatment of veterans. In 1932, thousands of military veterans who’d been made poor and destitute by the Depression marched on Washington, forming what they called a “Bonus Army” in protest. They’d all served in World War I and been promised a “bonus” for doing so in 1924—but one that functioned like a bond and wouldn’t actually be paid out until 1945. But the veterans were struggling now, so they demanded their bonuses early. Butler sympathized with them and traveled to Washington to see their protest encampment for himself, even making a speech there:

I never saw such fine Americanism as is exhibited by you people. […] You have just as much right to have a lobby here as any steel corporation. […] Makes me so damn mad, a whole lot of people speak of you as tramps. By God, they didn’t speak of you as tramps in 1917 and ’18.

Unfortunately, it was no use. Soon after Butler’s visit, then-President Herbert Hoover sent in the Army to disperse the protest. Tents were burned, tear gas filled the air, the veterans were driven out at gunpoint, and nobody got their bonus. For Hoover, it was a PR disaster, one that would contribute to his defeat by Roosevelt in the 1932 election. For Butler, seeing his fellow servicemen treated as disposable pawns was a shock that would alter his politics forever.

Finally, there’s a third important strand to this story: the rise of fascism across Europe. By 1934, Benito Mussolini had already made his March on Rome and been in power for more than ten years in Italy, and Adolf Hitler had recently been appointed as chancellor in Germany. In the United States, too, fascism had a degree of support—especially among the upper class—that’s shocking to modern eyes. As Noam Chomsky likes to point out, Fortune magazine ran an entire issue about Mussolini’s Italy in July 1934, writing in glowing terms about “The State: Fascist and Total”:

The young Kingdom of Italy—as yet but sixty-four years old—has found itself. Its people, once almost ashamed to acknowledge their nationality, now survey the rest of Europe not merely with a fervent but with an arrogant pride. Other nations falter or reel hysterically in search of unity. Italy is calm and united under the emblem of common strength and effort which is Fascism.

Yes, that’s a quote from a real editorial. Incredible as it might seem today, Fortune magazine—the same publication that runs cover stories about Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos today—spent the 1930s applauding the supposed achievements of Il Duce. They weren’t the only ones, either. Alf Landon, the Republican governor of Arkansas, said in 1933 that “even the iron hand of a national dictator is in preference to a paralytic stroke,” referring to Roosevelt’s agenda, and Republican Senator David Reed declared that “if this country ever needed a Mussolini, it needs one now.” The fascist sympathizers in the upper echelon of U.S. society weren’t even trying to be subtle.

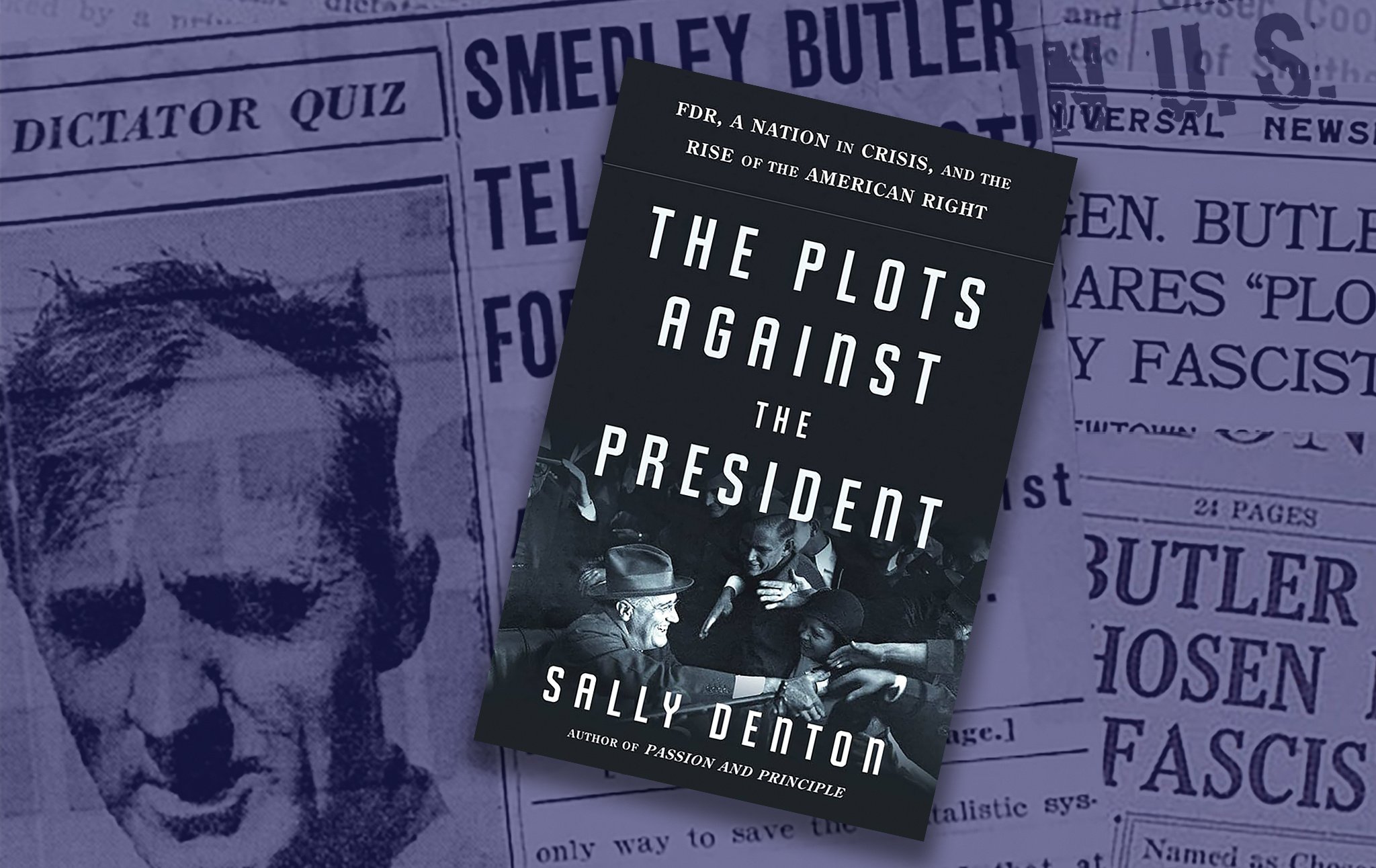

Take these three elements together—FDR, Smedley Butler, and rising fascism—and you have the ingredients of the Business Plot. But what actually happened? Well, to put it bluntly, some members of the American financial elite were so spooked by Roosevelt and the New Deal that they hatched a plan to overthrow him and install the American Mussolini of their dreams. It’s one of the least-known, but most important moments of the 20th century, and it’s been chronicled in depth in two recent books: The Plots Against the President: FDR, a Nation in Crisis, and the Rise of the American Right by Sally Denton and Gangsters of Capitalism: Smedley Butler, the Marines, and the Making and Breaking of America’s Empire by Jonathan M. Katz.

Both books are worth reading in full, but the gist of the Business Plot is this: Butler was approached in the fall of 1934 by Gerald C. MacGuire, a bond salesman with extensive connections on Wall Street. MacGuire had been trying to enlist Butler in right-wing political causes for a while, seeking to use his military reputation and influence among veterans to his own advantage. The previous year, he’d tried to convince the general to make a speech to the American Legion—which MacGuire had already commissioned for him—in favor of the gold standard. (Roosevelt had abolished gold as the basis of U.S. currency, but MacGuire and his associates hoped that if the Legion took up an official position against the change, he could be persuaded to reverse course—and thus protect their investments.) He’d offered Butler $18,000, a small fortune at the time, and said he represented several other East Coast financiers, including Robert Sterling Clark—the heir to the Singer sewing machine company, who’d served under Butler during the Boxer Rebellion—and Grayson M.P. Murphy, an investment banker who sat on the board of Goodyear, Anaconda Copper, and Bethlehem Steel. (Murphy was also the treasurer for the aforementioned American Liberty League.) Butler asked to meet the “principals” of the lobbying effort, and MacGuire introduced him to Clark, who was remarkably open about his plans to subvert Roosevelt’s economic agenda. As Denton describes the meeting in The Plots Against the President:

“I have got 30 million dollars and I don’t want to lose it,” Clark told Butler. “I am willing to spend half of the 30 million to save the other half.” Clark said he felt certain that if Butler made the speech in Chicago, the Legion would follow his directive and force Roosevelt to return to the gold standard. When Butler asked Clark why he believed that Roosevelt would be responsive to [an American Legion] resolution, Clark replied that when Roosevelt realized that it was his own patrician class directing the pressure, that he would willingly succumb. “You know the President is weak. He will come right along with us. He was born in this class. He was raised in this class, and he will come back,” Clark said. “He will run true to form. In the end he will come around. But we have got to be prepared to sustain him when he does.”

Ultimately, Butler declined to make the speech. But he kept up a relationship with MacGuire, wanting to know more about his Wall Street backers and their plans. Now, in 1934, MacGuire came to Butler’s Pennsylvania home in a black limousine, with a whole new idea in mind.

As Denton writes, MacGuire said he’d just returned from a tour of Europe, where he’d been learning all about fascism and the role of military veterans in fascist movements. He’d visited Italy, seeing Mussolini and his “Blackshirts” firsthand. He’d toured Germany and studied the growing Nazi movement, and done the same with Franco’s Spain. Finally, MacGuire had been in France and examined the Croix de Feu (Cross of Fire), a right-wing paramilitary made up largely of WWI veterans. This, he told Butler, would be the ideal model to bring political change to the United States. Once again being remarkably direct, MacGuire said his Wall Street friends had agreed to raise up an American Croix de Feu of their own, and they wanted Butler to lead it. Together they’d launch a soft coup against Roosevelt, who would remain the president but be reduced to a figurehead:

The plot was stunning in its presumption and simplicity. “Did it ever occur to you that the President is overworked?” MacGuire asked Butler. He explained that it did not require a constitutional change to authorize a “Secretary of General Affairs” to take over the details of the office of the presidency. The man the plotters had in mind for this task was Brigadier General Hugh S. Johnson, Roosevelt’s head of the National Recovery Administration, who, according to MacGuire’s purported inside information, was about to be fired by Roosevelt. “We have got the newspapers. We will start a campaign that the President’s health is failing. Everybody can tell that by looking at him, and the dumb American people will fall for it in a second” [MacGuire said.] The veterans’ army, led by Butler, would march on Washington and induce Roosevelt to step aside because of bad health.

“Stunning,” indeed. The plan was a grandiose one—but then again, not as ridiculous as it might initially seem. It’s worth remembering that, for most of his 33 years in the military, Butler had been in the business of overthrowing governments, suppressing left-wing political movements, and installing U.S.-backed dictatorships. What MacGuire and his cronies wanted to do wasn’t really so different from Butler’s previous interventions in places like Nicaragua or Haiti, with the exception that the coup on American soil was meant to be bloodless. Then, too, the 1932 “Bonus Army” had shown that veterans’ groups could apply serious political pressure to the U.S. government when they got together in an organized march. Additionally, FDR’s health issues—he had paralysis in both his legs—had been widely discussed in the media in the 1920s, even if his physical decline didn’t really begin until around 1943. So the plotters had reason to think the public might believe them if they enacted their plot and claimed Roosevelt had delegated his authority. Butler himself looked like the perfect ex-military strongman, and although the Business Plot was certainly ambitious, so were Mussolini’s March on Rome and Hitler’s seizure of power in Germany—and those had succeeded.

What the plotters didn’t realize, though, was that Butler’s political beliefs were rapidly moving left. The crushing of the Bonus Army had shattered his faith in the U.S. government he’d spent so long serving, and he’d begun to develop a conscience about his many imperial crusades. Just a year later, in 1935, he would write the landmark book War is a Racket, confessing that he had “helped in the raping of half a dozen Central American republics for the benefits of Wall Street” and condemning U.S. militarism as a gigantic scam “in which the profits are reckoned in dollars and the losses in lives.” The last thing he wanted was to help U.S. financiers overthrow democracy the way they already had in so many other countries, and he told MacGuire so, saying that “If you get 500,000 soldiers advocating anything smelling of Fascism, I am going to get 500,000 more and lick the hell out of you, and we will have a real war right at home.” He then blew the whistle to Congress and the press, even filming a newsreel where he exposed the plot.

In the months that followed, reactions were mixed. The New York Times dismissed Butler’s account of the plot as a “bald and unconvincing narrative,” treating the whole thing as a joke. But then again, the Times had claimed twelve years earlier that “[H]itler's anti-Semitism was not so genuine or violent as it sounded,” so its reporting wasn’t exactly infallible in this period. For its part, the congressional committee that took Butler’s testimony concluded that “There is no question that these attempts were discussed, were planned, and might have been placed in execution when and if the financial backers deemed it expedient.” But the committee never released its full report, and even Butler’s full testimony wasn’t printed in the major newspapers, appearing only in the left-wing New Masses magazine. More disturbingly, the names of all the “financial backers” never came out, and no one was ever prosecuted for their role in the scheme. In a BBC radio documentary, journalist John Buchanan speculates there was a simple reason for this: FDR himself may have struck a deal, allowing the organizers of the plot to escape treason charges if they ceased their agitation against him.

So what lessons can we draw from the Business Plot today, as Donald Trump and his MAGA movement rear their heads? One is that we need to be very clear about who poses the actual “threat to democracy” in the United States. Despite the dramatic imagery of January 6, the gravest danger doesn’t actually come from street-level rioters like the ones who invaded the Capitol. Rather, it’s the wealthy people and organizations who stand behind right-wing movements—the ones who’d never dream of dirtying their thousand-dollar suits in a “Stop the Steal” rally—that we really need to worry about. In 1934 it was the Robert Sterling Clarks and Grayson M.P. Murphys of the world who wanted democracy gone. Today it’s the Rupert Murdochs, the Elon Musks, the Peter Thiels, and the Leonard Leos. The average Trump supporter, all fired-up by Fox News and social media posts, is not the enemy of democracy; they’re just deluded and misled. The people running Fox News and the social media platforms are the problem.

What’s more, the history of the Business Plot shows that democracy and capitalism are fundamentally contradictory forces. This is important to understand, because liberal and libertarian thought claim the opposite: that capitalism and democracy are allies. In this worldview, “free markets” are just another kind of freedom that a liberal society should afford people, along with freedom of speech, religion, and other civil liberties. Allegedly, free markets allow people to “vote with their dollars,” as if the ability to choose one product or corporation over another were the epitome of democracy. Government-run economies, meanwhile, are considered undemocratic and synonymous with tyranny. The slogan of Reason magazine, the foremost libertarian publication in the United States, reflects this dogma: “Free Minds and Free Markets.” But as the Business Plot shows, this is completely false. A society that “votes with its dollars” cannot be truly democratic, because it will always be dominated by the people with the most dollars to throw around.

As long as you have economic inequality, you don’t actually have democracy. What you have is a faux democracy with invisible fences around it. The economic elite will tolerate your elections and your “democracy” as long as it always delivers the outcomes they want: most importantly, free markets and the sanctity of property. But if an elected government strays beyond the fences, as Roosevelt began to with the New Deal, the elite will step in to stop it, and what the majority of the people might want or vote for is completely irrelevant. We see this pattern today, too—from unelected “superdelegates” tipping Democratic primaries toward business-friendly candidates, to Super PACs that spend millions to influence the outcomes of congressional elections, to an openly corrupt Supreme Court striking down abortion rights that the majority of the American people support. There are all kinds of antidemocratic levers of power, some more subtle than others.

Ultimately, only one side can get what it wants. A nation’s economy can be controlled democratically by its elected leaders, who attempt to make decisions in everyone’s best interest, or it can be controlled undemocratically by bankers and shareholders, who only look out for themselves. But it can’t be both. For finance capital to flourish, democratic influence over its operations has to be curtailed. Likewise, for democracy to flourish, capital has to be curtailed.

Really, the Business Plot is a mild example. A little later in the 20th century, in 1970, Salvador Allende was elected democratically as the president of Chile and tried to implement a popular socialist agenda, nationalizing his country’s mineral resources so his own people could benefit from them instead of U.S. corporations. For that offense, the United States backed a brutal military coup against him and installed the Pinochet dictatorship that would ravage Chile for the next 20 years. They did the same in Iran in 1953 and in Guatemala in 1954. Since then, less has changed than you might think. In 2019, yet another U.S.-backed coup overthrew the government of President Evo Morales in Bolivia, and Elon Musk decided to just state the views of his class openly, posting online: “We will coup whoever we want! Deal with it.” That, in less than 140 characters, is the relationship between capitalism and democracy. And is there any reason to think that “whoever we want” wouldn’t also include the government of the United States, if Musk and his fellow billionaires deemed it necessary?

The last takeaway from the Business Plot, though, is the most important: that the world’s economic elite aren’t invincible. They failed in 1934, all because one person refused to go along with the plan. Even a Major General in the Marines, it turns out, is capable of seeing through decades of lies and ideology and choosing a new path. That means there’s hope. Democracy—and I mean real democracy, not the hollow imitation that pits red capitalists against blue ones in meaningless Coke-or-Pepsi contests—can win. Smedley Butler beat the wealthy fascists of his day, and so can we.