Is James Baldwin Nostalgia For The Better or Worse?

In his 100th year, there's a danger in celebrating Baldwin without recognizing his true radicalism.

The year was 1968 and James Baldwin was sitting by his hotel pool in Palm Springs, California, being interviewed about a forthcoming writing project when a phone was brought out to him with breaking news. The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. had just been assassinated. In his essay “The Shot that Echoes Still,” Baldwin recalls the terror he felt on that evening:

I hardly remember the rest of that evening at all, it’s retired into some deep cavern in my mind. We must have turned on the television set if we had one, I don’t remember. But we must have had one. I remember weeping, briefly, more in helpless rage than in sorrow, and Billy trying to comfort me. But I really don’t remember that evening at all.

Yet another comrade in the struggle for Black liberation had been murdered. This terror at what the white world would produce led Baldwin, inevitably, to abandon his project—a planned biopic script about the life of Malcolm X, who was assassinated in 1965.

From the beginning, Hollywood tried to water down the ferocity of Baldwin’s Malcolm X script. In The Devil Finds Work, Baldwin recalls a memo from a Columbia Pictures executive advising him that “the writer (me) should be advised that the tragedy of Malcolm’s life was that he had been mistreated, early, by some whites, and betrayed (later) by many blacks: emphasis in the original.” The executive also wanted to avoid any suggestion that Malcolm’s trip to Mecca had political implications. As D. Quentin Miller noted in the African American Review, the studio sought a “sanitized and carefully controlled version” of Malcolm’s life, removing its political edge. Baldwin wanted Billy Dee Williams to play Malcolm, but the studio pushed for actors like James Earl Jones, Sidney Poitier, and even Charlton Heston. Baldwin refused to compromise and walked away, saying he’d make the film “my way or not at all.” Later, in No Name in the Street, he reflected that “The Hollywood gig did not work out because I did not wish to be a party to a second assassination”—this time of Malcolm’s legacy.

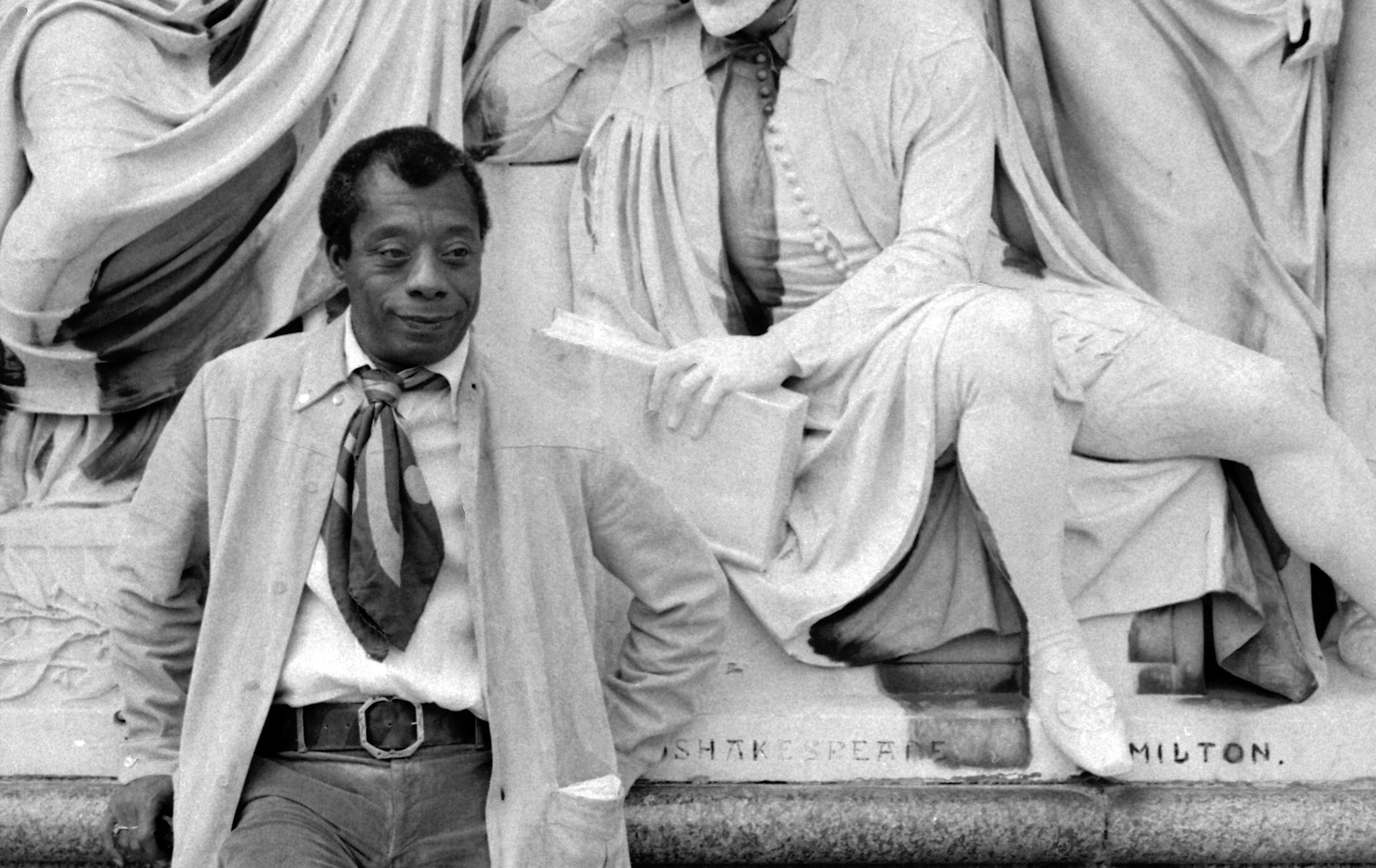

James Baldwin, born in 1924 in Harlem, NYC, was a bisexual, Black writer who wrote prominent works like The Fire Next Time, Giovanni’s Room, and Notes of a Native Son while challenging the literary and political establishment to do the right thing in the face of injustice. His advocacy in the Civil Rights and Black Power Movement, as well as his artistic versatility, have continued to inspire since his death in 1987. Throughout his career, Baldwin was deeply aware of the need for artistic integrity in a world determined to destroy Blackness by any means. He understood that how we depict important Black figures matters. Today, the struggle to honor Black legacy, especially Baldwin’s, remains incredibly relevant. As mainstream media commodifies and sanitizes revolutionary Black figures, there is a growing risk of reducing their radical contributions to mere symbols of diversity or inclusion.

In 2015, Ta-Nehisi Coates released Between the World and Me, a meditation on his son's awakening to the dangers of being Black in America, framed by the murder of Trayvon Martin. The book is inspired by Baldwin, who wrote The Fire Next Time in a similar format, as a letter to his nephew—and it soared, winning the National Book Award and twice making the New York Times Best Seller list. Coates’ acclaim marked a wave of Baldwin nostalgia, and a renewed mainstream interest in Baldwin's work and life. This renewed interest has led to acclaimed film projects like Raoul Peck’s 2016 documentary I Am Not Your Negro, in which Baldwin is one of the main subjects, and the forthcoming Baldwin biopic planned by POSE actor Billy Porter. There have been other efforts of commemoration, like Parisian walking tours to places that Baldwin frequented. Despite these efforts, the central question remains, as Tara Phillips, the current executive director of La Maison Baldwin, puts it: “What [does] his honor demand when it comes to honoring him? Or what did he want?”

Dr. Cornel West, a revered Black liberation theologist, has stated that Baldwin served as “the great Black hope” of his time to white moderates and liberals as he debated on public stages and did the labor of articulating the horrors of white supremacy, sometimes to his exhaustion. Today, we face a similar choice. Will we merely celebrate Black figures, like Baldwin, through selective quotes and stories? Or will we emulate his fearless stand against colonial and imperial violence, whether for Palestine or Black America?

In recent years, the dangers of the co-optation of Black radical legacies have become more insidious. Following the 2009 inauguration of the first Black president, Barack Obama, many claimed that America was in a “post-racial era”—a claim that became more complicated with the rise of the Black Lives Matter Movement in 2014 and calls for racial justice and prison abolition coalescing during the 2020 George Floyd rebellion. As these movements gained traction, the complexities of how Black radicalism has been sanitized and repurposed for mainstream acceptance became more apparent. In today's landscape, this co-optation has taken on new forms, warranting a closer look.

One of the most notable examples of Black radical co-optation is that of Martin Luther King Jr, who by the end of his life began to expand his public discourse beyond Civil Rights and towards a more radical international approach to liberation, including economic justice and calling out America’s imperialist violence in the Vietnam War. Since his death, this more radical side of King has been obscured, and his legacy has been distorted by all kinds of unscrupulous political figures. One of the most glaring examples came during the 2024 U.S. Presidential Election, when Republican candidate Vivek Ramaswamy claimed recklessly that MLK Jr. would be in favor of book bans censoring Black history. Or there’s the 2015 film Stonewall, which was promptly criticized for whitewashing the June 1969 riot at Stonewall Inn in New York City—which is widely believed to have been sparked by Black and Latinx trans activists, including Marsha P. Johnson, who don’t appear in the film at all. Ironically, much of this co-optation mirrors Baldwin’s warning in his 1969 speech, The Artist’s Struggle For Integrity:

The crime of which you discover slowly you are guilty is not so much that you are aware, which is bad enough, but that other people see that you are and cannot bear to watch it, because it testifies to the fact that they are not. You’re bearing witness helplessly to something which everybody knows and nobody wants to face.

To those who love Baldwin, this section of his speech is a call to radically confront others for their complicity in the face of systemic violence, like the struggle for Palestinian liberation today or the United States’ role in global imperialism. Likewise, there are those today who “cannot bear” to acknowledge Baldwin’s true radicalism.

Since Baldwin died in 1987, the fascination with his life, travels, and work has taken many forms in the cultural zeitgeist. In Paris, the second city that Baldwin is most associated with, walking tours are an option for Baldwinites invested in learning more about the city. One notable tour group, Entree to Black Paris, was started in 2018 by Monique Wells and her husband, Tom Reeves, to highlight the history of Black Americans and Africans expatriating to the city. Their “Baldwin in Paris” tour takes visitors to prime locations of Baldwin’s Paris ranging from Cafe de Flore, where he wrote much of Go Tell It On The Mountain, to various places in the city where Baldwin lived.

The notion of a James Baldwin pilgrimage has also materialized in acclaimed literary works of the last few years, where Black authors retrace Baldwin’s steps to draw contemporary conclusions about racial progress. Some of the works in this mini-genre include the 2019 book Afropean: Notes from Black Europe by Johnny Pitts and Begin Again: James Baldwin’s America and Its Urgent Message for Our Own by Eddie Glaude Jr.

In Afropean, Pitts signs up for a walking tour in Paris similar to the one Wells and Reeves run, and then ventures to Saint Paul de Vence, a town in the South of France where Baldwin lived for 16 years until his death. He visits the dilapidated property that was once Baldwin’s home, ruminates on the lack of visible commemoration of Baldwin there, and moves on with the understanding Baldwin is always with him because “his spirit lay in a book in my backpack.” In Begin Again, Eddie Glaude Jr. juxtaposes Baldwin’s racial reckonings with present-day movements fueled by the Black Lives Matter Movement and Donald Trump’s presidency. Throughout the book, which was a New York Times bestseller, Glaude Jr humanizes the lesser-known Baldwin, who escaped to Istanbul to confront his political disillusionment and sometimes struggled to take care of himself.

Many of these efforts to commemorate Baldwin speak to a desire among Black Americans to know a deeper version of Baldwin than the one typically offered to us by the media and education system. They resist a diluted version of Baldwin that soothes the current status quo. And just as Baldwin himself struggled with Hollywood over the appropriate way to honor Malcolm X, the tension underlying Baldwin nostalgia has fueled significant criticism of a forthcoming James Baldwin biopic today.

In April 2023, the Allen Media Group announced a forthcoming James Baldwin biopic to be co-written and acted by Billy Porter. As Baldwin himself noted in The Devil Finds Work, “you can make a fairly accurate guess as to the direction a film is likely to take by observing who is cast in it, and who has been assigned to direct it”—and although the biopic project initially appeared hopeful, a 2024 Guardian interview with Porter was immediately met with backlash. When asked about Baldwin’s support for Palestinians in the interview, Porter claimed ignorance of the ongoing genocide in Gaza, saying that “I don’t want to be in the conversation, because I don’t know enough about it” despite being a vocal supporter of Israel since 2021. “It’s not a part of the script – his civil rights work in America is what we’re focused on,” Porter said when asked about the political scope of the film, “More than what he thought about the crisis in the Middle East.”

Porter’s America-centrism goes against Baldwin’s righteous support of colonial struggles abroad, whether highlighting the Algerian struggle for liberation from France in No Name In The Street or penning a 1979 letter in support of Palestinian liberation. In his “Open Letter to the Born Again,” published in the Nation, Baldwin both rejects antisemitism absolutely and indicts the nation of Israel as a colonial project:

But the state of Israel was not created for the salvation of the Jews; it was created for the salvation of the Western interests. This is what is becoming clear (I must say that it was always clear to me). The Palestinians have been paying for the British colonial policy of “divide and rule” and for Europe’s guilty Christian conscience for more than thirty years. Finally: there is absolutely—repeat: absolutely—no hope of establishing peace in what Europe so arrogantly calls the Middle East (how in the world would Europe know? having so dismally failed to find a passage to India) without dealing with the Palestinians.

The real Baldwin, as shown in his words, sharply contrasts Hollywood’s version, especially as Porter’s avoidance of Baldwin’s stance on Palestine undermines Baldwin’s commitment to truth over political safety—his insistence on saying the things “which everybody knows and nobody wants to face,” no matter the cost. Since the Guardian interview, Porter has received criticism online from countless Baldwin lovers for that exact reason, even leading to a petition calling for his removal from the film which has received more than 7,000 signatures.

In contrast, Tara Phillips, the Executive Director of La Maison Baldwin, understands the complexity of how some people attempt to commemorate Baldwin’s legacy for better and for worse. The organization began in 2016. While working at a charter school in Brooklyn, Phillips organized student visits to Paris, which included walking tours that mentioned Baldwin’s significance. Since taking the role of Executive Director, Phillips has concentrated on nourishing the organization’s relationship with Baldwin’s family.

When I spoke to Phillips earlier this year, she was reflective. “The centennial, in particular, has been a double-edged sword,” she said. “Because what I have been discovering is that there are so many people that latch onto his legacy or use it in a way to enrich themselves that I was kind of naive to when I took the job.”

The centennial of James Baldwin’s birth this year offers a chance for collective reflection and action. For La Maison Baldwin, this looks like a Paris festival honoring Baldwin’s 100th birthday and exploring a theme of “Truth, Liberation, Activism,” along with forthcoming artist residencies for Black writers in cities around the world that Baldwin loved. For other Baldwin lovers, conscious commemoration can take many forms, like personal Baldwin pilgrimages or bookstores in his honor, like Baldwin & Co. in New Orleans.

But there is a danger in the bookstores and festivals, too—the danger of turning Baldwin into a mere commodity to be bought and sold, or a harmless icon separated from today’s struggles. Beyond them, there is a deeper call to confront hard truths about power, privilege, and the courage it takes to live fully and honestly in this world. Answering that call isn’t just about honoring Baldwin’s memory; it’s about carrying his fire forward—bearing witness to injustice and refusing to look away.

We must resist the state and imperialist violence Baldwin condemned, whether it's student protests against war profiteering in Palestine or movements like Uncommitted, fighting to dismantle the stranglehold of the two-party system in the United States. Baldwin never shied away from exposing the brutal systems of oppression in his time, and neither should we. His legacy demands more than remembrance—it demands action.