How Workers Everywhere Can Win

Labor studies professor Eric Blanc explains why worker-to-worker organizing is critical to fighting Trumpism and building a more just society in the long term.

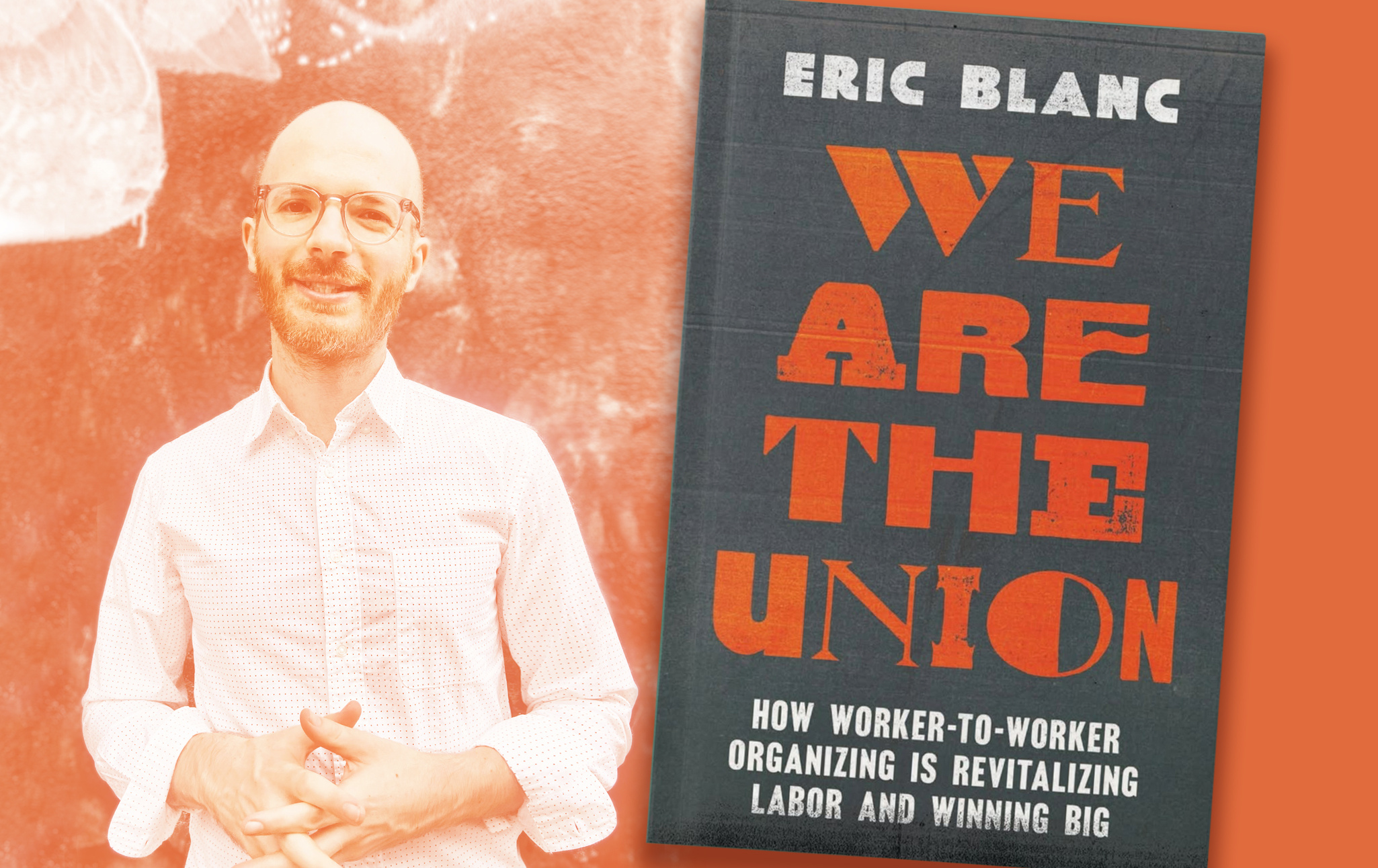

Eric Blanc is the author of We Are the Union: How Worker-to-Worker Organizing Is Revitalizing Labor and Winning Big, which covers the recent wave of unionization drives in America and summarizes the lessons we can learn from them. Eric shows that today's new unions have succeeded against incredible odds through bottom-up organizing: the workers themselves decide to organize a union, rather than existing large unions launching campaigns. Eric argues that we can learn from what baristas and Amazon workers and media workers have been doing and that there is a substantial possibility of reversing the ongoing decline in unionization rates. His book is a vital toolkit for those seeking to transform their workplaces and the world, and he joins to day to give us clear, concrete lessons that he gleaned from hundreds of interviews with union members around America.

Nathan J. Robinson

You and I are talking at a moment where I think a lot of people on our side are feeling demoralized because there has been a right-wing takeover of the apparatus of government. The billionaire class seems to have won some major victories. And so I would begin by encouraging every single person listening to this on the program or reading the transcript version to pick up this book immediately if you want to feel energized, if you want to feel like there's a plan and there's something you can do. Your book is a hybrid of a playbook and also a piece of academic scholarship, but I think this is a pretty forward-looking and encouraging work that you've produced.

Eric Blanc

Well, thank you. And that was the goal. In addition to, as you mentioned, trying to explain what's going on, a major impetus really was to give a shot of hope. No matter who's in power, it’s hard living in this world and not feeling despair, but I think that union organizing really is one of the few things that continues to give me hope, and it's also just one of the few things that you can do no matter what. No matter who's in power, you always have the capacity to go speak with your coworkers. You can go on strike. And that's a form of power that is just always there. It's not tapped as much as it should be, but that's my eternal spring of optimism. It's always a power that can be tapped.

Robinson

Well, tell us a little bit more about the moment that we're in for labor. It's mixed. You certainly have some very discouraging infographics in your book. Figure one in chapter one shows the relationship of inequality and union strength in the U.S. And just to give a summary here: inequality—that is, the share of national income that is held by the top 10 percent—starts high. It drops as union density goes up in the 1930s and '40s, and then as union density undergoes its steady decline from a peak of around 35 percent to where it is now, which is hovering around 10 percent, the income share of the top 10 percent of the country goes up and up and up. This is a dispiriting picture. On the other hand, there's one little infographic here, one little chart, that shows us a tiny little uptick that may give us a little bit of hope and confidence in the last couple of years. So tell us a little bit about where things stand historically and what we've seen in the last couple of years.

Blanc

Yes, the big picture is still that we're in the midst of a moment in history of rampant inequality, of billionaire control, and we haven't turned that around yet. And I think, just generally speaking, the crisis of American society and really of the world at this point is deeply rooted in this power imbalance between bosses and workers. So that's the terrain we're on. The exciting thing is that really since 2018, workers have taken action and have organized on a scale that we haven't seen in many decades in the United States. So listeners and readers might remember the teachers strikes in 2018. You had hundreds of thousands of teachers in red states—West Virginia, Arizona, Oklahoma—taking action and winning. So that got the ball rolling. And then we've seen workers across Starbucks, Amazon, and the auto industry organizing, most of the time from below, not waiting for union leaders to signal that they should or to give support. Workers have taken the initiative, and this has created a different dynamic where all of a sudden the labor movement is in the headlines. People are excited about the labor movement. They're winning first contracts, they're winning concessions. And we're at a moment now where it remains to be seen what will happen.

There's still momentum. There's still this fighting spirit. To me, this recent labor uptick is something that poses a possibility, not just for winning these campaigns that are already going on, but it shows a model for, really, what the rest of the labor movement and what progressives, more generally, should do on how you can win at scale, how you can beat the billionaire class.

Robinson

Well, to be specific here on the picture, as I understand it, it is the case that we have seen an increase in the number of workers in unions, but we have not yet seen an increase in union density, that is, the percentage of workers in unions. Is that correct?

Blanc

Yes. To get into the numbers, hundreds of thousands of workers have joined unions since 2021. So these are some of the biggest numbers we've seen in the last 50 years. About 100,000 workers joined last year, almost 100,000 the year before, and a little bit less the year before. So this is a large number of people. You're talking about 300,000 people. This is not chump change. The only reason that union density hasn't turned around is that the economy itself actually has been expanding. There's very low unemployment, and so it hasn't been at the scale necessary to turn around union density numbers, but it is actually quite a lot of workers, and they're building power. So both things are true. It's both been extremely exciting and still far short of what it needs to be to really transform the country.

Robinson

In that hundreds of thousands statistic that you cited, for every one of those people, there's a story. Every single one of those hundreds of thousands of people either organized, worked on an organizing campaign themselves, or was organized by someone. So what you did for this book is hundreds of interviews. You're not just recapitulating press accounts. This is a work of original research that required a ton of interviews with people who had actually been on these campaigns to get to the bottom of what happened. How did these come about? What are the models here? Tell us a little bit about the people that you've talked to.

Blanc

Personally, I just find it incredibly inspiring to talk to workers who've organized their workplace. I could basically do that every day. There's almost nothing better. And the stories are always different. There's always particularities of the workplace and this person, but there's a universal kind of dynamic. So I'll talk about that and give a couple of examples.

The universal dynamic is that really ordinary people did heroic things. And it's remarkable because it's a big risk. It is a risk to organize your workplace. I think about Maggie Carter. Maggie Carter is the Starbucks worker who organized the first Starbucks in the South. She had a little kid during the pandemic—single mother entirely on her own—and, nevertheless, took the risk to unionize her workplace in Tennessee and ended up having a crucial role in spreading the Starbucks campaign across the South. She explained to me that she did it because she wanted her son to live in the type of world that he deserved instead of just hunkering down and trying to get by individually like so many people do. She understood that it was going to be by building collective power, that she was going to be able to both build a better world for her son, and frankly, to model what it was to be a good mom. She talked a lot about that. She wanted to show what the labor movement was and show how important it was to take a stand for her son and to be a good model.

And so you have across the economy in different industries, whether it's auto, whether it's journalists, whether it's fast food, people like Maggie who risk getting fired. And I'd ask them, were you worried about getting fired? Everyone said, yes, in this country where labor law isn't strongly enforced, it is a risk you can potentially get fired. Most didn't because they had large numbers, but they took that risk, and not only did they win—most of the stories contain big wins—but I found particularly moving how often they described that the process itself of organizing was something that just they cherished. They describe it in almost reverential terms. They had felt lonely and isolated before, and by building a union with their coworkers, all of a sudden, they had this really rich community, had new friends, and they saw sides of people they'd never seen before. Really, their lives were transformed by this camaraderie. And in a moment in the U.S. where people feel very isolated, that's one of the aspects of unionization that oftentimes gets overlooked. It's not just about getting the raise. It's about finding meaning, and it's about finding a connection to people beyond yourself. And I hope I told those stories well in the book.

Robinson

One of the Starbucks baristas said:

“Unionizing has taught me how to advocate and speak up for myself in all areas of my life. I've found my motherfucking calling, dude. There's nothing else I'd rather be doing during late stage capitalism. Is it stressful. Of course. Is it difficult? Nothing worth fighting for is easy. Is the company going to gas light and manipulate you? You bet. But don't quit. This is everything.”

And you have a photo right above of the delighted Starbucks baristas. And this is such a common story as people feel a power within themselves that comes out that they didn't know that they had. People find bits of themselves.

You open with a story of a woman who was organizing coworkers in between chemotherapy sessions. These are just incredible people, but they're also ordinary people who became conscious of their power and became determined to do something about an injustice.

Blanc

Right. There's a reason I start the book with that story. I found it very moving. That’s [Salwa], a Starbucks worker in Connecticut. She had stage four Hodgkin lymphoma and decided, with the time left on the earth—and thankfully, she’s still alive, so she made it through, but at the time, she didn't know what would happen—she just said, I have no idea what's going to happen with my life. I may or may not make it through, but what I want to do is make the time count. And so she spent her whole time unionizing her coworkers. And she's going around after chemo talking to her coworkers—literally, she talks about the best time for her where she had the most amount of energy, because she didn't normally, is right after they give her the steroids for chemo. So just think about that. To me, I get just a tremendous amount of hope from knowing that humans can do these types of extraordinary things, and I think the union upsurge has been full of them.

Robinson

Now, I want to get into one of the core arguments of your book. Your book's thesis is not just that the labor movement is good. The subtitle is “how worker-to-worker organizing is revitalizing labor.” And earlier in this conversation, you used the phrase “bottom up versus top down.” And one of the core points that you make is that if we accept the premise that rebuilding the labor movement is important for all kinds of reasons—and you say at the beginning of the book that the stakes could not be higher, and you explain why you think this is so crucial—if we wish to do that, you're talking about different paths to doing that, and you advocate a particular model. So tell us a little bit more about that.

Blanc

Yes, so part of the reason I talk about these inspirational stories of workers is because my argument in the book is essentially that workers taking the lead is the only way you're going to be able to unionize by the millions, and you will have to unionize by the tens of millions to actually turn things around. So worker-to-worker organizing is essentially a form of labor organizing that we've seen recently—in Starbucks, in media, in auto—but its defining characteristic is that it just depends far less on staff than traditional organizing.

So in a normal staff-driven campaign, the best practice is you have one staff person for every 100 workers. And that can be, at its best, very effective. I'm actually not trying to argue that staff is unimportant or that resources are unimportant or expertise is unimportant. That can be really effective. When you have a good staff organizer, it can be very empowering, and they can win. The problem is, you just can't win widely enough because it's so expensive. There's literally not enough money, enough time, enough staffers in the country to be able to organize tens of millions of workers that way. And that's part of the reason why the labor movement isn't doing enough organizing. It's so cost intensive. So my argument is that not only are these recent campaigns inspirational and exciting to read about, but this is essentially the type of model that we need if we're going to turn things around for the labor movement.

Robinson

Does that suggest that we just need to wait for these things to pop up organically? Or are there ways in which these kinds of campaigns can be seeded and encouraged?

Blanc

Yes, that's a good question. One of the knocks against this argument when it's been made in the past—I'm not the first person to make a similar case—but the knock has been, well, you're just romanticizing workers; you're waiting for this sort of spontaneous explosion; and, we live in the real world, that's not going to happen. The argument I make is, yes, to a certain sense, that's true. We can't just wait for millions of workers to rise up. The tricky thing, and the crucial step, is actually to figure out ways to seed the idea of unionization to millions of workers.

So to give an example of what that looks like, look at what happened with the auto workers. The auto workers had a massive strike in the fall of 2023. They went on strike against the big three, and they won. Now, most unions would have just called a victory. They would have said, okay, great, we won this. But the auto workers were much more ambitious. They were looking at a more worker-to-worker direction. And they used that moment in which the whole country was watching them—Shawn Fain was getting interviewed every night on television—and they used that spotlight to say, okay, all workers in the auto industry in the South, we’re calling on you to start self-organizing. So they seeded this idea.

Workers across the country were saying—auto workers in particular—we'd love to get a 33 percent raise, a 45 percent raise. And the union said, okay, not only should you do that, but we're going to support you in doing that: Jump on this national call, fill out this form—we're going to give you the tools you need to start self-organizing. And that ultimately ended up leading to the first union auto factory in the South winning a union election at Volkswagen in Tennessee. Now we see the movement continuing to spread.

So this idea of seeding is partly using high attention moments to call on other workers and to give them the tools to start self-organizing, but it can also be something as simple as salting. Salting is a crucial tactic that I talk about in the book in which mostly young radicals get jobs at particular workplaces and strategic industries with the conscious goal of unionizing them. That type of salting activity is another way where you can get the initial ball rolling, even without a lot of staff, because you're a worker and you can relate to your coworkers as someone else who's on the shop floor. We saw that at Amazon, and we saw that at Starbucks.

And I would just put a plug in, actually, for anybody listening to this show. I would imagine that Current Affairs listeners and readers are potentially a target demographic for salting. You really should consider it right now. This is one of the crucial ways we're going to keep the momentum up over the next few years. And you should reach out to me. It's very easy to get my email online, and I would love to connect any listeners to organizing in a strategic industry. So, yes, definitely reach out on that.

Robinson

One of the things I understand you argue is that many existing unions have been insufficiently committed to growth, insufficiently committed to thinking about how to support every worker in the country who would love to start trying to organize their workplace but has no idea what to do. And I've talked to people before who have salted where a union has pulled the plug on the campaign, and it's been very dispiriting. And certainly, when the late great Jane McAlevey was on the program, she was very critical of many unions for failing to invest in and support these bottom-up efforts. Obviously, we want to be careful about criticizing the fellow members of the labor movement because we're all in this together. But tell us a little bit more about what you think every union should be doing to make sure that they are helping the rest of the movement grow.

Blanc

The reality is that the vast majority of unions aren't trying to grow. So it's not true, as it's often said in the media, that this inexorable decline of the labor movement shows there's no future for organized labor—presumably something about the economy, or something about contemporary American life, makes it impossible for unions to grow. The reason I am skeptical of that, although who knows, is that most unions aren't trying to grow. They're not putting money towards growth. The vast majority of unions, at most, are trying to service their existing memberships. And most union leaders are, frankly, not thinking about what it would take to expand the union. They don't have a conception that the stakes for their own union are tied deeply to the organization of the rest of the working class. Most of them think that it's still possible to just skate by with how things have been, and that's becoming more and more untenable with Trump, the economic crisis, and climate change.

But the vast majority of union leaders are extremely risk averse. They're extremely narrow minded, and insofar as there's some sort of broader perspective, it's linked to a kind of deferential approach towards lobbying the Democratic Party. The vision of change, in so far as exists, is that hopefully we elect the Democrats, they'll pass labor law reform, and then maybe down the road, we'd be able to organize large numbers of workers. And this doesn't mean they're bad people. I think union leaders are often very honest, hardworking people, but it's a practice and a vision that can literally only lead to more union decline.

And so the crucial thing that would need to happen is a massive investment in new organizing. There's been a lot of good recent research on how much money the labor movement has in its coffers. There's $38 billion in net assets sitting there, over a third of which is highly liquid. This is just an unprecedented amount of money. Even 10 years ago, labor didn't have this amount of resources. So there's a huge war chest that could be used, not only to beat back Trump's attacks but to go on the offensive. And nevertheless, unions are sitting on that, and they've sat on it over the last four years, despite an extremely favorable context for new organizing. And if there isn’t more of a push from below, from rank and filers, or some sort of change from above—though, maybe the Trump situation will shake things up—then, frankly, there's not much chance that they will make a turn towards new organizing.

Unions should be funding at least 30 percent of their budgets towards new organizing. That was a goal that was floated in the 1990s—the goal of organizing at least one million workers in unions was a goal that was floated by the AFL-CIO in the early 2000s. So actually, we know what kind of investment is necessary and possible. It's a question of will.

Robinson

Well, that is an argument for a change in how union leaders approach organizing. But let's talk more about, until such time, a central reason why anyone—everyone—who's not even part of a union today should pick up your book. You show what workers can do on their own under adverse circumstances without much external support from an existing organization. We were talking about how you're not making the romantic argument that there's going to be a spontaneous burst of unionization across America's workplace. What happens is things are seeded. And in the story that you tell and the interviews you collected, surely, one of the things that you found out was what inspired people in the first place. So when you talk to people, what tends to be a common story about how it got into people's heads that they should start an organizing campaign?

Blanc

It's a really important question. And one of the novel dynamics of the last few years has been the extent to which labor organizing has, for lack of a better term, gone viral. So there's a copycat dynamic at play. To give one example, the Starbucks workers were organizing in Buffalo, New York, and this was actually initially intended to be a purely regional campaign. There was no intention of even trying to organize Starbucks nationally. They were trying to organize coffee shops basically in the Buffalo region. Then they win one union election in the fall of 2021, and somewhat to their surprise—actually, very much to their surprise—they get inundated with emails and calls from all across the country saying, how did you do that? We want to do the same thing.

And so what happened is, in part, because they were media savvy—they were posting things on social media—and they were testing the waters to see if other workers might be interested, well, it went viral. It caught the imagination of other workers who had been experiencing similar sort of traumas under the pandemic—similar insecurities, similar dashing of expectations. Starbucks said it was a good employer. It turns out, it sucks. That context was so widespread, there was fertile ground where it just took that one spark, just one store in Buffalo, for then, all of a sudden, literally hundreds and eventually thousands of workers to say, if they could do it, I can do it, too.

And so that's essentially been the pattern of the recent unionization uptick. It has been this inspiration, this copycat dynamic, in which one high-profile battle, and not even necessarily a win—not even necessarily did they win every time. Think of one example: the Amazon organizing, in many ways, started with a loss. There was a union election in Bessemer, Alabama. Listeners and readers might remember this. They lost their election, but it was just the very act of workers fighting back. There was a lot of attention and enthusiasm about it, and that's what inspired the workers at JFK8 Staten Island warehouse—Chris Smalls and company—to turn their very nascent and somewhat chaotic and inchoate organizing effort into a union effort because they saw what happened in Bessemer.

They saw that's a path we could take. It's a path that people are excited about and gets a lot of media attention. Why don't we do that? So you can see that even sometimes when you lose the immediate battle, you can end up inspiring others to fight back as well.

Robinson

But how do they win? When they do win? Because they are facing formidable odds. This worker-to-worker organizing approach is difficult because you have no money and you have no experienced union staff helping you. You're really out there on your own, and you're profiling people who, many of them, again, have never done this before. They're figuring out everything, often independently. They're learning lessons on their own. I'm sure some of them study history, or they talk to people. But when you've talked to people, and they're like, here's what we learned, we wish you could put this in your book so that other people would know this when they started—we wish we'd known it when that we started—what's the takeaway there?

Blanc

A few different takeaways. One is, and I think this goes to how you framed the question, it's not actually the case that all of these drives, especially the ones that won, [were done by workers] on their own. Part of the argument of the book is that workers should take the lead. You don't need to wait for a union to start. But ultimately, especially if you're going to win in large numbers against really powerful corporations and companies, you do need some level of resources. You don't need the extremely heavily-handed staff of the dominant approach, but in the drives I profiled, there were, ultimately, some staff that supported. They had some lawyers. They have these things that are important as a back end kind of scaffolding to support a worker-to-worker—worker led—drive.

Okay, so part of it, I think, has been—and this is something that workers themselves realized, for instance, at Amazon—that they started as a purely independent effort, and they've recently affiliated with the Teamsters, which, for all of its limitations and contradictions, is an organization that's seriously committed to organizing Amazon and that has the resources to help sustain this bottom-up organizing. So one thing they realized through their experiences, is that, actually, we don't have the ability to just do it purely on our own. We do need to work with an existing union because the battle will be a long one. And I would say that’s one.

And the second lesson I would stress is that it does take a while if you're going to beat a major corporation. That's not something that you're likely to see in an extremely short amount of time. Of the smaller companies, many won their union election and won a first contract. But at Starbucks, they're still fighting for a first contract. It's been four years in now, almost. At Amazon, it's going to take even longer. As a point of comparison, it took 20 or 30 years to organize the major mass production industries in the 1930s, I think, with General Motors and Ford. There were lefties and young people and activists trying to organize them for a long time. So if you're looking for a quick fix, at least if we're talking about organizing the biggest companies, it's different.

When you're going up against a smaller employer, it's easier, frankly, to win. But if you're going up against the biggest companies, you need to be prepared for the long haul. And part of the argument of the book is that workers are doing that, and they're sticking it out at jobs in which their turnover rate is normally extremely high. Often at these jobs, you're out after half a year. We have workers sticking it out because they become so committed to the effort and so committed to the camaraderie with their coworkers that they understand that they have not only a possibility but a responsibility to stay at the job for the long haul, to see through the victory, through all of its ups and downs towards the first contract.

Robinson

The last time we spoke to Jane McAlevey on this program, we were talking about that second phase where you've won your election, everyone's elated, but then you have to get the contract. Her last book was about this, the second half, and how to win in the negotiations that ensue. And one of the troubles is that it's extremely difficult to get. The Amazon labor union, I believe, has not succeeded in getting Amazon to the table to negotiate a contract with them. But one of the points that you make, and I'll just go to page 135 of your book, is that even before these unions have won a contract, you highlight the importance of pre-contract changes won by local unionization efforts. And you say, interestingly and importantly, “wherever workers band together, a workplace rarely remains the same.” And you give all of these examples of cases where these campaigns may not have gotten to a contract yet, but they actually forced important concessions out of the employer nonetheless.

Blanc

Yes, and I think that's a crucial point you make, and it's often lost. It's not true that the only way you make changes and win things is with a first contract. That's a great and important goal that can take a while to get to. But part of the way you sustain your morale and your movement is that you win all sorts of things along the way, if you're organizing in a serious way. If you're weak, then they won't give you anything, but if they're scared of you, they will make major concessions. And so we've seen that at Amazon, there were major pay bumps after the first union election. For Starbucks, major changes have been won across the board. Also, some small things. I think you might remember, there's these small anecdotes that I like of how individual stores change.

So, for instance, at one store they unionized, they finally got rid of the beehive that had been stinging everybody that management refused to get rid of, even though it was in the back of the store. So you have these small changes, like getting an abusive manager fired. The power of organizing is such that companies will try to stave you off by giving some concessions. But those concessions, in turn, can be used by good organizers to say, look, when we organize, it's getting results, don't give up.

And the last piece of these kinds of pre-concession, pre-contract concessions and wins that is worth stressing—we talked about it a bit before—is that the win isn't just the external policy win around wages or whatever. It's also just the win of workers feeling meaning and feeling power and having a sense of community with your coworkers. And one of the quotes I really like in the book is, you might remember Michelle Valentin Nieves, who's an Amazon worker at the JFK warehouse. She says the warehouse isn't the same. The supervisors aren't as cocky as they used to be. And if somebody has something done to them, we're all going to go up en masse and march on the boss. It's that feeling of work not just being an authoritarian dictatorship but some place where you can have a voice and be contested. That's true, not only when you get a first contract. That can be true if you're organizing in a serious way along the way.

Robinson

Can I tell you my favorite anecdote in your book? It is the stable hand from the Medieval Times Castle union, who said that with the relations between the staff, we definitely got closer. The Queens never used to talk to us stable hands. And so the medieval hierarchy broke down.

Blanc

I love that quote. I think he actually says that the Queens never remembered our names, even though they were written on our shirts. You can imagine how much unionization changes—

Robinson

It ended feudalism!

Blanc

Exactly.

Robinson

You talked about sustaining morale. Oftentimes, these are years-long campaigns. What you said for the big companies, if we look at the historical precedent, this is a project that's going to take decades. And even in other places, they said, these are really tough fights. They're very demoralizing. People get fired, and there’s a lot that people have to endure. A mutual acquaintance who's been on the podcast, Paul Waters-Smith, when he was in college worked with the Pomona College dining hall workers. The whole time he was there, they were working on this organizing campaign. And every time he went back, they're still working on the campaign. He graduated from and left college, and years later, was still working on the organizing campaign for the dining hall workers. Finally, they won the organized campaign for the dining hall workers. But it was very tough. It took years. People gave their lives to this.

So what are the lessons on how you sustain? You also talk about organizations that have found it difficult to sustain their energy. You mentioned things that were so exciting, like the Bernie Sanders campaign and the Sunrise Movement, that had not succeeded in building lasting, massive, popular infrastructure.

Blanc

Yes, that's a good point of comparison, I think, because those were both extremely important and exciting efforts. I was very deeply involved in the Bernie campaign. But a limitation that I think we see more clearly now in hindsight, is that because they weren't fundamentally democratic projects, they weren't projects in which the membership could determine what would happen, then, it meant that they ended up not being able to sustain themselves. Bernie actually just closed up shop with the campaign infrastructure, against what some volunteers would have wanted to see. There was a massive infrastructure that could have potentially continued, but they had no ability to debate what should happen to this massive infrastructure because it was an electoral campaign. And electoral campaigns tend to be top down, that's their nature. But if you're going to sustain things, then you do need to give people more ownership over the process. And democracy is hard, and I think anyone who's ever been to a really long meeting can understand that there's always going to be some tensions between efficiency and democracy.

Okay, so with that caveat being said, you need a real sense of ownership and a real practice of democratic functioning for people to stick with an effort for a long time. There's just no way that people are going to pour so much of their energy, their hearts, their sacrifices in daily life for an effort in which they don't feel like, actually, they're able to have a meaningful say in the direction of how things go. So part of it is the democracy piece, and I think the second piece—I wouldn't say it's a necessary precondition, but it sure helps a lot, honestly—is if you have some sort of political vision.

There's a reason why so many of the people who have taken the lead in these union drives and who have stuck it out are socialists or leftists of one form or another. And I think the motivating factor for them is not only the changes they want to see at work. That's a major part of it. But there's also this deeper impulse to make the world a better place, to make history, to be part of something bigger than yourself, and to see, ultimately, your struggle at that workplace as part of this very long, centuries-long, battle against capitalism for a more democratic future, for a democratic economy and country and world. And so when you have that long-term vision, then it makes the day-to-day setbacks and annoyances and all that easier to deal with. They are still frustrating, and it can be heartbreaking. But by placing yourself in that continuum, that legacy, and with that long-term vision, it's just easier to sustain. You're getting your meaning, not only by hopefully winning this first contract but by how you see yourself as being part of and helping build this bigger movement. Whatever you win in the short term will be contributing to empowering working people to fight back.

Robinson

You are very clear that you believe that there is a historic opportunity right now, despite the election of Donald Trump, which I don't think was certain at the time that you finished this manuscript, but certainly was not unforeseeable. You say in the conclusion of your book, “history will not look kindly on union officials who sleepwalk through the best opening for labor organizing in generations.” We've talked about how we can seed these kinds of efforts, but you quote a United Auto Workers strategist saying that seeding is one word for it, but Chris Brooks’s word is that

“We should be arsonists, fanning the flames of workplace organizing because there's a tinderbox out there. Inequalities out of control. People are upset about their lives and the conditions they operate under. The anger is there. So how do we dump gasoline everywhere to help workers spread and deepen as many organizing fires as possible?”

So, let me put that question to you because he asked the question there: How do we dump gasoline everywhere? What have you concluded about that? How do we light that organizing fire?

Blanc

The first thing I would say is maybe where we started, which is, people need to understand that all is not lost because Trump is in office. The biggest obstacle we have right now is that so many people are feeling despair and demoralized and, as they put it to me, want to go into political hibernation for the next four years.

And I understand that sentiment. I get it. And especially with the horrors in Gaza and climate disasters, it can feel overwhelming, but it's not the case that we have to go gently and succumb to everything that Trump wants to do over the next four years. To the contrary, labor is in a very good position were it to choose to use its potential resources and power to defeat Trumpism. Not only is this important for the scaling up of unionization, not only is that important for beating back economic inequality, but I think that at this moment, the institution and the type of organizing that is most crucial for defeating Trumpism is the labor movement. Because think about what it would look like over the next couple of years if the labor movement spent 30 percent of its budget on new organizing and called on all workers to fight back against their companies?

Right now, the companies are almost indistinguishable from the Trump administration. You have the richest men in the world at Trump's inauguration. So if you want to fight Trumpism, unionize Tesla. You want to fight against Musk—if you're a Twitter/X worker or whatever, you have power there. You have disruptive power. So there is, I would say, a role to play, to understand the unionization effort as not only possible but necessary under Trump.

And just fanning the flames more generally. For listeners who I assume tend to be of the more leftist variety, let me just give two last plugs for what you could do. One is, I already mentioned you should salt. You really should. If your job sucks, and you don't like it, why not get a job that sucks that you don't like that's actually meaningful because you're changing the world, and you're part of an organizing effort? And so again, reach out to me. I'll connect you to unions who are very eager to onboard you to these very exciting campaigns.

And the second is, if you're in a workplace that doesn't have a union—most workers fit that bill—you should reach out to the Emergency Workplace Organizing Committee, which is a project of DSA together with the United Electrical Workers Union. You basically just go to workerorganizing.org—it's a website—and if you are somebody who doesn't have a union and/or if you just want to see even just a raise at work, go to that website, fill out that form, and what will happen is, within 72 hours, an experienced organizer is going to call you back and to talk through with you how you can start winning those changes you need to see at work. And so you don't have to just wait around. I think that the difficulty sometimes is it feels like the labor movement is something else—the labor movement is somebody else. Well, no, the labor movement is all of us, and it should be you, and you literally can, right now, go fill out that form and talk to an organizer and think through how you would start organizing at work, whether it's to make concessions from the boss, or it's to build a union.

And I do think it's particularly incumbent on leftists who haven't given up and who have this long-term vision and who haven't succumbed to political hibernation to take the lead right now. If we're able to start getting some wins in the short term and show that people are fighting back against Trump and that he's not invincible, that can very easily turn the energy around and turn the tide politically in this country. So I think that's what we need to see.

Robinson

Well, on that encouraging note, to our listeners and readers, you heard Professor Eric Blanc: go out there, build the movement you wish to see in the world. There is no time like the present. We have a historic opportunity. As you point out in this book, and as labor points out over and over, there are millions of us and very few of them. And, ultimately, those who do the work have the power. Ultimately, Elon Musk doesn't build a car. He's never built a car in his life. There are people who build his cars for him. Elon Musk doesn't run Twitter. He tells people what to do, and those people could tell him what to do instead. This is the fundamental fact that organizers have to point out to workers and make people conscious of. Ultimately, all the power is in their hands.

Blanc

Yes, that's exactly right, and I think that hopefully more and more people are starting to see that. It's interesting because the labor movement hasn't turned around union density, but we are in a moment where people are talking about the labor movement in a way that we haven't seen and that is really promising. The labor movement is a thing that people can get into. It's a thing that people debate in a way that even just 10 years ago was not the case. So, yes, that basic analysis that you have is an idea that is percolating more widely than it has in a long while.

Robinson

I just read an article in the Wall Street Journal saying power is shifting back towards the bosses after it shifted towards the workers over the past few years—the Wall Street Journal being a paper that acknowledges the existence of a class struggle but who [is on the side of the bosses]. It quotes all these bosses who are delighted that they don't have to listen to their employees anymore. But the point is that they're scared. They're very scared because they've seen what can happen. The Amazon labor union was a huge surprise to Jeff Bezos, and I'm sure Starbucks did not anticipate this unionization wave. There have been successes. These successes are profiled in your book. You talk about how people got these things done. You talk about the fact that this is practical and can be accomplished. The opportunity is there.

Transcript edited by Patrick Farnsworth.