How to Read Nietzsche

Is Nietzsche best categorized as a reactionary or a champion of personal liberation? Daniel Tutt, author of a new book on Nietzsche's thought, weighs in.

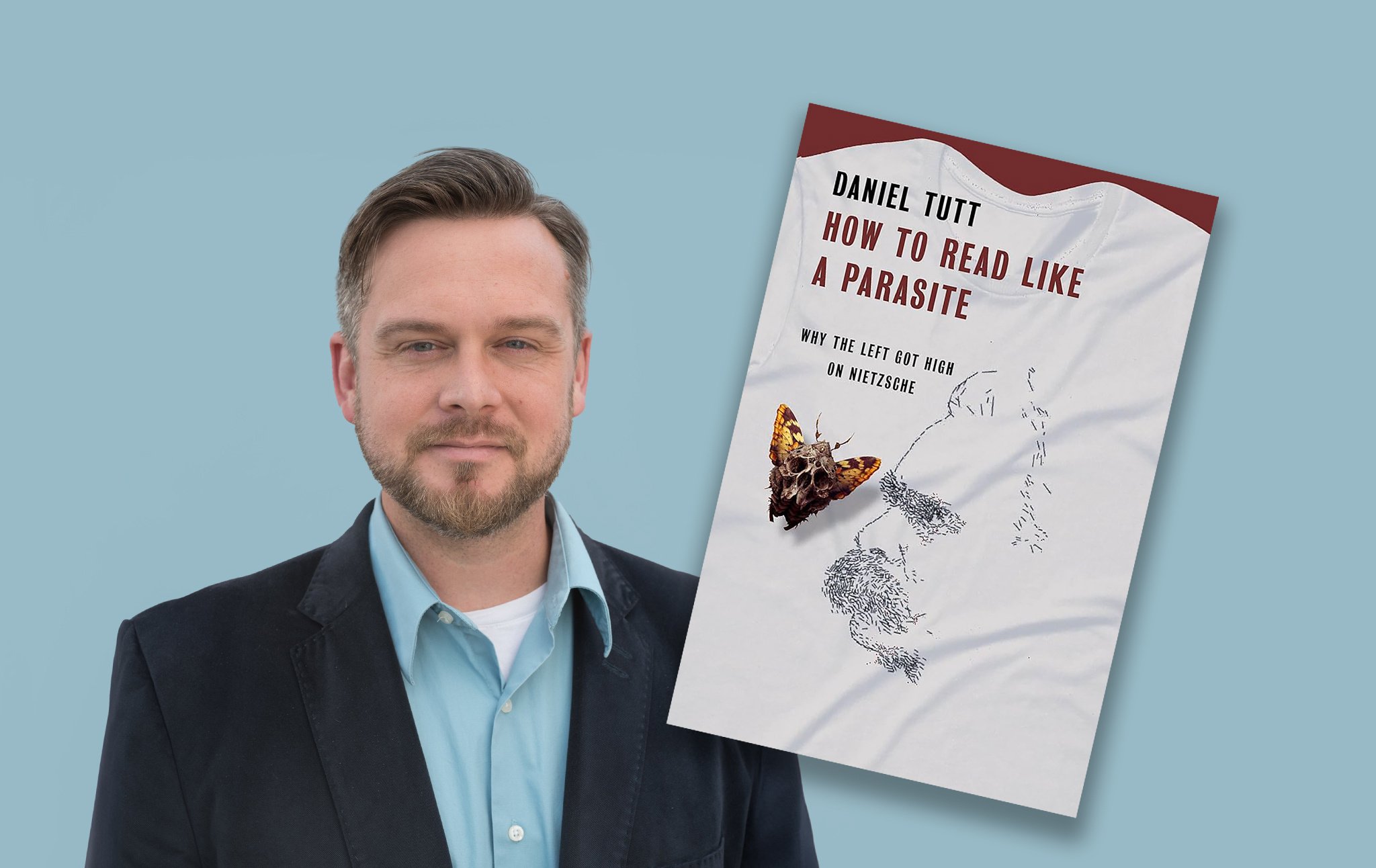

Friedrich Nietzsche was one of the most influential philosophers of all time. Interestingly, thinkers on both the right and left have found inspiration in Nietzsche, and his ideas show up everywhere from the anti-democratic elitism of H.L. Mencken to the liberatory politics of the Black Panther Party. There is an ongoing debate over whether Nietzsche is best categorized as a reactionary or a champion of personal liberation. Today we are joined by Daniel Tutt, whose book How To Read Like a Parasite: Why The Left Got High on Nietzsche offers a stinging critique of Nietzsche's core philosophical ideas, while arguing that we still ought to read and engage with them.

Nathan J. Robinson

I'm ready to dive in to some 19th century philosophy with you. Nietzsche has been dead a long time, and one might wonder why you thought it would be of value to write an entire book dissecting and critiquing the thought of Nietzsche. Let's assume that we're speaking to listeners and readers who have absolutely no familiarity with his writing, who have heard of him and know he was a 19th century philosopher. Maybe they've heard the word “Übermensch,” and that's about what they know. So tell us more about why it is important to think and write about Nietzsche.

Daniel Tutt

Well, part of the argument I make in the book, of course, is that we live in Nietzsche's world. So, concepts such as our personal values—we are partially indebted to Nietzsche for bequeathing to us the idea of the death of God. There's the idea of perspectivism, the idea of the eternal return of the same. Nietzsche is an inventor of very sticky concepts, and has mesmerized popular and academic audiences, and even before he died, he became a cult sensation. There's actually a lot written about the Nietzsche cults that emerged in Germany and beyond.

Nietzsche was born four years prior to the great 1848 worker rebellions, where Marx and Engels penned The Communist Manifesto. He's born into a family of a Protestant preacher, and his father dies when he's a young boy of a mysterious brain disease. Nietzsche is an extremely precocious student. He excels. He's put into private education, a classical education, and at the young age of 24 he becomes a philologist and a professor at the University of Basel. And Nietzsche at that time, as a young man, befriends one of the most famous intellectuals across Europe, Richard Wagner, who was a musician and a philosopher in his own right. They then begin an artistic and esthetic relationship, and Wagner becomes like a muse to Nietzsche, and Nietzsche pens his first text, The Birth of Tragedy, in the political backdrop of 1872, which is a very important moment politically in the European Western history because it is the moment in which the Paris Commune takes place. The Paris Commune was the first moment in which the working class actually seized the governmental apparatus in Paris, and Nietzsche writes in a letter to a friend that this is the saddest day of his life because there was a rumor that the Communards—the anarchists and the socialists in the streets of Paris—had burned down the Louvre, the famous French museum.

Nietzsche creates a sort of very esoteric political philosophy, which is highly esthetic. His first book, Birth of Tragedy, is actually a text about music, but it's sort of a politicization of music. And one of the things that's been very interesting about Nietzsche is, how do we get at the veiled or esoteric dimension of his political thought? You have to understand, as an inventor of concepts, Nietzsche actually introduces and makes an intervention into philosophy proper. He's the inventor of a very important notion of what's called perspectivism, and perspectivism comes out of a notion that the centered subject, the subject of Descartes, the subject of reason—this kind of autonomous subject for whom their dispensation of rationality and knowledge is under their rational purview—Nietzsche disrupts that. Nietzsche introduces what Freud would later elaborate under the notion of the drives. Nietzsche theorizes the human being as largely governed by irrationalist impulses that are largely de-centered from their rational faculties. So, Nietzsche is a great disruptor of Western philosophy.

And at the same time, he writes in a style which is extremely seductive, in what's called an aphorism. It's sort of a poetic style that is written in a short, highly accessible, punctuated mode, and this is what allows Nietzsche to have a readership way beyond the academy, way beyond just stuffy academics. So that's one thing you have to understand about him.

Robinson

Can I just pause there? You say he's seductive in a way. You write in the book about your first exposure to his writing and why he is so compelling. He's kind of known for appealing especially to young people. Nietzsche books are classified, along with Kurt Vonnegut books, as books you might discover as a teenager that blow your mind. And it's not just young people. You point out that it's leftists, conservatives, great writers like Jack London and H.L. Mencken, and French theorists. What is it about Nietzsche that pulls people in?

Tutt

That is part of the mystery of Nietzsche. I think part of it, Nathan, is the fact that Nietzsche has this energy through the aphorism that leaps beyond the page. So, he conveys his ideas in what he calls a gestural style. [...] One of the most important concepts of Nietzsche, of course, is the genealogical method, which is this idea that we can track the origin of values that we socially share in common, back in through the history of thought. Nietzsche says that his genius is found in his nostrils. Nietzsche claims that his genius, and what makes him so alluring, is found in his capacity of being able to detect—being able to smell—what he calls decadence.

Nietzsche becomes a social critic of what he calls the nihilism of European society. Part of the reason that he is so alluring is that he makes a critique of modernity, the world that we still live in, in many ways, that feel extremely fresh. Nietzsche says that he writes for the philosophers of the future, and moreover, those philosophers of the future are not exactly understood as academic philosophers. I said that Nietzsche got his academic post at 24, but he resigned at 38, and he basically led a Bohemian traveling life. He goes on long walks every day, and he writes in this inspired way, writing in his journal at a mountain peak in Switzerland, and then comes back and formalizes this through the aphorism. And basically, in the late 1870s and early 1880s, Nietzsche has an extremely productive writer, where he basically published almost six or seven books a year.

So there's something about this movement of Nietzschean thought which is very much engaged in this highly reflective social critique that has just captivated people. It's captivated people across the entire class spectrum. There was once a survey right after Nietzsche died which asked, who's the most popular writer among industrial proletarian workers? It was Nietzsche—Marx was sixth on the list. So that actually shows you that what Nietzsche is capable of doing is mesmerizing philologists, trained philosophers, and the layman alike. That's a very unique thing.

Robinson

You mentioned workers reading Nietzsche, and I mentioned young people, left theorists, and kind of cultural conservatives—many different people—but it strikes me that what a lot of those people have in common is feeling dissatisfied with or alienated from the society they live in. People who have no discontent might not see what's of value in Nietzsche, but when people who suspect that there is something wrong with the world around them encounter his work and find explanations of what has gone wrong and what could be right, what is it that he shows them? He says, this is what you have to understand about the world. What is it?

Tutt

Nietzsche's vision of the world is what he calls the tragic vision of the world, and it's an interesting historical and political vision. As a young person who came to Nietzsche, I had very few tools to actually contextualize. Again, Nietzsche calls himself a propagator of the tragic worldview, but also a propagator of what he calls an untimeliness, and he calls himself one of the great hermits. He never marries. He says, any philosopher in modernity that marries and has children is really not a philosopher. So there is a profound asceticism in Nietzsche, and a lot has been written about his theological and religious upbringing, and how he transposes that, or performs what he calls a transvaluation on the Christian morals and values of his youth.

So part of what I argue Nietzsche does is build a type of community. And yes, you're right, that community attracts people who are isolated and who are lonely. But, it just so happens that the forces of alienation, an effect of modernity, makes a lot of us that way. It's only natural that Nietzsche will connect with you, and when you read Nietzsche, you do feel a sort of self-help, but of a sophisticated variety.

There's nothing commodified about the self-help that Nietzsche offers. It's rigorous, it's erudite, it's strong. Nietzsche has a huge emphasis on preserving strength. One of his core ideas is that modernity is eradicating the possibility of individual genius. We talked before about Nietzsche's view of the Western individual. Part of the community that he's trying to build is meant to preserve a particular form of individualism that Nietzsche believes to be massification, or the movement of democracy, of socialism, of liberalism, of everything that was opened in the glorious French Revolution—Nietzsche becomes a thinker who's trying to build a community that is literally 180 degrees from these egalitarian socialist movements, which are seemingly sprouting up all around him.

Again, he's born four years after 1848. He writes his first book right as the Second Reich in Germany under Bismarck forms, and one of the things we know about the Second Reich in Bismarck's Germany is the fact that it's basically one of the first large-scale social democracy experiments. You have introduced social insurance for the first time. You have what Nietzsche calls a new type of intellectual entering the European scene, what he calls the philosopher journalist, who he thinks is a Philistine intellectual. So, there's a type of radical elitism in Nietzsche that he wants to preserve. Nietzsche therefore becomes a very stealthy reactionary thinker, but here's the interesting thing: you could read Nietzsche and walk away and say, I don't really see the elitism, and that's actually the heart of my book.

Robinson

Yes, this is really important. I didn't realize until reading your work that one of the things that attracts people to the writings of Karl Marx is the vision for what life could be like for people: fish in the morning, poetry after dinner; to end your alienation to feel like your true self; that you do your work for yourself and not just a component of a giant machine designed to produce profit for somebody else. And one of the things that is compelling about Nietzsche is that he offers people something similar, a feeling of what true freedom could be, how you could live well, and how you could have the fulfillment of a great and heroic life. Before we get to the deeply reactionary politics that you argue underlie all of this and why you think we ultimately need to reject Nietzsche's vision, talk a little bit more about the promise that he gives to the reader of what they could and should be.

Tutt

Right. Well, part of what this is about is the class dynamics ushered in by what Wagner calls the age of revolutions, which was ushered in by the 1848 worker rebellions, The Communist Manifesto and so on, of which, by the way, Wagner welcomes. Wagner takes himself as kind of a left-wing philosopher, artist, etc. Nietzsche does not. The cause of their break is a whole other story. But Nietzsche becomes very concerned with how what you might call the ruling class can preserve culture. So why does Nietzsche look out at the Paris Commune and the worker uprisings and feel sadness? This goes back to Nietzsche's view that the ancient Greeks—remember, he's a philologist, an expert in the Greeks—had developed a conception of society, and particularly of the maintenance of suffering. Social suffering is a big motif in Nietzsche’s writings. Many philosophers have argued that one of the ingenious things that Nietzsche does is place human suffering at the very center of his metaphysics. And what concerns Nietzsche is the rise of a set of egalitarian movements for equality that are basically trying to argue that the subordinated working class should not be a subordinated working class any longer. And Nietzsche is saying, wait a second, if this comes to fruition—universal male suffrage, the rights of the working class, etc.—it will actually result in the incapacity for great culture, for great thought to happen.

So he called his movement the Free Spirits, which was a very interesting choice if you study the history because the Free Spirits was literally the opposite of a very popular socialist movement at the time called the Free Thinkers. So, Nietzsche gives a series of lectures to the German intelligentsia, for example, on the future of our public education system in the Second Reich, where he is pinpointing this problem of massification, of movements for equality. And so what I argue is part of that is about the invention of a new type of thinker—the invention of, as I said before, a new type of philosopher. And that's sort of what the Nietzschean project is about.

It's so fascinating because we have to also understand that as Nietzsche matures—when he writes his work, such as Thus Spoke Zarathustra, he adopts dramatic personae, and a lot of what goes on in Nietzsche is prophecy. Now that may sound strange, but it's sort of a secular prophecy. A lot has been written about this. Nietzsche is sort of trying to invent a direction that Western civilization could take. There's a highly grandiose project at work here, and when you're reading it, you are being inducted into some kind of secular, quasi-religious community. And many folks have written, actually, about how Nietzschean concepts have a secular religious quality to them. I hope that gets at part of what you're asking.

Robinson

But I suppose a basic question that I think your book is very heavily concerned with is that for Nietzsche, the Paris Commune is horrifying because: what about culture? What about the Louvre? You've said that he looks upon the movements of workers to break their chains as something disturbing, which raises the question, why would the student protesters of May '68, the New Left, the Black Panthers—the subtitle of your book is, Why the Left Got High on Nietzsche, so how does the left get high on Nietzsche when at the core of his philosophy there seems to be a loathing of socialism?

Tutt

This is a great mystery, Nathan. I have an argument here, which is that the left used to not get high on Nietzsche. And part of it is the notion of parasite: it’s parasitical. It's a book, really, about a reading method. How do we approach this figure to extract this esoteric political dimension and put it to use? And one of my arguments is that Nietzscheism should actually be perceived as an antagonistic philosophy to Marxism, if we define Marxism as a philosophy: a worldview that is centered on the activation of working-class consciousness. And so my argument is that the left makes a mistake when they adopt Nietzsche as the primary muse or the primary philosopher of the left.

Robinson

Well, yes, but why? Why would they?

Tutt

Why they do that is an interesting story. Part of it has to do with the Cold War and the politics of translation. You have to understand that, after the war, Nietzsche was basically a done deal. And I'm not making the claim that the Nazi philosophers were bringing the best interpretation of Nietzsche. I'm not saying that, but it is a fact that they abused and incorporated the Nietzschean elitism. People call Nietzsche the spiritual godfather of the eugenics movement. Nietzsche has aphorisms that are for the annihilation of the weak, for extermination, etc. The Nazis appropriate Nietzsche in a certain way.

So, after the war, most Western academics and German specialists in the West are prepared to abandon this philosopher. However, it's very interesting, because who controlled the Nietzsche archive at the Goethe and Schiller Institute? It was actually the Soviets in East Germany, and there began a translation process of huge unpublished fragments of the later Nietzsche. And what happened, basically, is that we had in France a renaissance in Western philosophy. Michel Foucault, Gilles Deleuze, Pierre Klossowski, George Bataille—all of these names that we're very familiar with that became super popular in the 1990s in American academia, under what is known as French Theory. They were interested in challenging the roots of Western metaphysics. They were interested in challenging the idea of the subject, of the individual, of the author, and Nietzsche became their muse. That popularity spilled over into a philosophy that happened concurrent to what? To the ossification of socialism under Stalin.

So when Stalinism became a brick wall for the advancement of Marxism in the West, Nietzsche enters in to replace Marx for many Western thinkers and therefore for the masses. So, '68 and even the movement of libertarian socialism and the uprisings that happened in Italy in the late '70s are largely philosophically driven by a kind of left-wing Nietzscheanism. I argue that those forms of left-wing Nietzscheanism are problematic. I call them elective affinity because, for example, with Deleuze, he wrote a manifesto called Nomad Thought in the early 1960s where he basically says that Nietzsche is the most important thinker for the left because Nietzsche—this is his argument—helps the left to discover the counterculture. Nietzsche’s philosophy can be used to help us transcend the repression of welfare state capitalism, the repressive bourgeois family, the repressive norms—the Vietnam War is happening, etc. So, Nietzsche becomes this libertine philosopher through French Theory. I can tell you about my problems with that form of left-wing Nietzscheanism, and I can also share with you a left-wing Nietzscheanism that I think is more interesting. You mentioned Huey Newton. There's also Kurt Eisner and Jack London. Those left-wing Nietzscheans are very different from French Theory left-wing Nietzsche, and I make a strong distinction there. We can talk about that if you wish.

Robinson

What I wanted to dwell on here is your reading and argument of Nietzsche seems like it should be obvious or inarguable: Nietzsche is an explicitly aristocratic philosopher. I'll just quote you here.

"He intended for his philosophy to be a prevenative strategy against what the egalitarian social movement of the French Revolution had brought to the world historical scene. Nietzsche's concepts are meant to pacify any changing of the status quo, to ensure that rank order is maintained and then any unruly Plebeian or working class is kept in place, if not eradicated as an agent of social transformation."

He didn't like socialism. He didn't like what we might call the sappy parts of Christianity about loving thy neighbor just because he's thy neighbor, turning the other cheek, etc. And as you note, a lot of this has been kind of buried, and it's easy to miss, but if you're a careful reader, you can see all the parts that are pro-slavery and that could very easily be used by a movement like the Nazis to justify a belief in eliminating the “untermenschen”: the weak and the pathetic, the people who have no culture and are intended for a natural life of slavery and what have you—or the “bug men,” as the Bronze Age Pervert guy now calls that, who’s very inspired by Nietzsche. So I get how Nietzsche inspires reactionaries. The mystery is why there even is a left Nietzscheanism. So, you've given us a little hint of how. Tell us a little more about how someone can construct this other version, this alternate Nietzsche, because it seems like it would be very difficult.

Tutt

In the book, I perform a genealogy of left-wing Nietzscheanism. One of the things you should realize is that because Nietzsche was trying to preserve something aristocratic amidst egalitarian movements of modernity opened by the French Revolution, a lot of left-wing thinkers have argued that we need to incorporate an aspect of Nietzsche's thought in order to activate the proletariat into a sort of dialectical transformation of the status quo. And the first thinker that does this is a very interesting leader of a successful socialist revolution in 1918 by the name of Kurt Eisner.

The Revolution of 1918 is not talked about much—obviously, the Russian Revolution of 1917 is talked about a lot more—and the reason for that is because Eisner basically created a kind of Bohemian government that didn't last too long. But you see, Eisner and the Bolsheviks were wrestling with Nietzscheism, what we can define as the cultural atmosphere of Nietzsche's elitist philosophy, which is very much implicitly in line with capitalist hierarchy. Nietzsche's philosophy is what we call romantic anti-capitalism. Romantic anti-capitalism is a very interesting concept, which is basically a tendency that emerged after 1848 in European thought. We see this a lot today as well—it's a very troubling fact. Usually, it is the left intellectuals who have a strident critique of capitalism. Romantic anti-capitalism is a critique of capitalism from the right. Usually, it's a nostalgic interest for returning to a bygone era. So it's an imminent critique of capitalism, but it's not a critique of capitalism that wants to overthrow capitalism. No, it usually wants to replace capitalism with a new elite. So you see, you have to incorporate this because in a revolutionary sequence in the early 20th century, Nietzsche became this parasite figure that activates the working class and also helps contest the ruling aristocratic ideals. That's an interesting historical moment, as I mentioned before, that once we get to the Second World War period and after, Nietzsche is reintroduced almost in a completely different way. This is what I call the hermeneutics of innocence, which is an ahistorical version of Nietzsche that we get from French Theory primarily, but other sources as well, that I find to be problematic because they center Nietzsche as the main philosopher of the left. [...]

Sometimes without knowing it, we're still looking for a philosophical compass. Some have argued that Marx needs a supplement. This is why you have things like Freudian Marxism, that the insights of Freud teach us something about human desire and subjectivity that Marx couldn't address. Others argued that Nietzsche has an aesthetics, a vision of culture, that is necessary for Marxism. Here's my argument. I'm not an anti-Nietzschean. The title of the book is not anti-Nietzsche. No, my argument is Nietzsche should be an appendage of Marxism, but not the driver of Marxism. So I want to learn from Nietzsche because I think there's a lot to learn from him if we read him in a proper historical context. That's sort of the argument, because there's actually a whole position on the left which is stridently anti-Nietzschean. I think that that's a sort of foolish position, in part, because I do believe that we live in Nietzsche's world. I do think that his thought has actually shaped us, shaped our culture. So it's too vulgar for me to just be sort of anti.

Robinson

Well, yes. But let me give you the vulgar argument, which is, here you have a philosopher who has the traits that I just described, that is to say, a contempt for weakness, a contempt for the idea of human equality and brotherhood and the dismantling of unjust power and hierarchy—all of the things that draw people to movements of solidarity. I don't know that solidarity was a concept that would have tugged on Nietzsche's heartstrings that much. What can you find, then, in such a philosopher? What is worth keeping? Why would you say that we need to retain any aspect of what he has to teach?

Tutt

Well, because the right is stridently and unapologetically Nietzschean. Because Nietzsche has such a keenness for preventing egalitarian movements from below. Again, my claim is that Nietzscheanism is a comprehensive philosophy that seeks to pacify all of that. Therefore, it's important for us to get on the inside of that and to upend it, and ultimately, to transcend Nietzsche. Nietzsche doesn't need to remain the philosopher of the left at all. No, what I'm calling for is a political and historical reading method that contextualizes his thought in a way which can be productive because Nietzsche identifies things about human resentment, for example. He has a very famous concept you're probably familiar with, which is called ressentiment. It's not exactly invented by him—it's a French neologism concept, which actually refers to a type of social suffering. There are many different interpretations of it, but my interpretation of it is that it's a type of social suffering in which the human being is unable to produce values. So Nietzsche has this notion of transvaluation of values, and he has this notion that political movements have actually been highly influenced by this. And I show, for example, in my section on the Black Panthers, they read Nietzsche kind of parasitically—Huey Newton in particular—and they were drawn especially to this idea of transvaluation of values. Transvaluation of values, in this sense, has to do with the way in which the linguistic status of the values that interpolate us, that influence us, can be modified at the level of language and how we invest in them. And so, basically, Huey Newton experiments with a new language for mobilizing and activating the black working class in America. That's a perfect example of how one can learn from Nietzsche, by using a particular concept of his, in this case, transvaluation of values.

But I also show that ressentiment also becomes a sort of lesson for understanding how capitalism can pacify the lower class. Basically, people impoverished have internalized a sense of defeatism, a sense of weakness that harms the possibility of large-scale solidarity and mobilization at a mass level. Nietzsche knew that. What's important is that we understand what Nietzsche wanted: he wanted to keep things that way, of course. Well, ultimately, for Nietzsche, he wants them actually to be happy and content. What he doesn't want of the working class is for them to be politicized. So you have to sort of get into the Nietzschean labyrinth to piece that out. There's a great Italian Marxist historian, Domenico Losurdo, who says that Nietzsche is more political than Marx because Nietzsche looks at certain domains of social life and history in his genealogical method, say, within the family, and he finds politics. Again, this notion of, I smell politics where it's never been smelled before. So if you really want to be a political actor, it's very important that you read Nietzsche. He gives you some tips on how to see politics. That would be one way to look at it.

Robinson

I suppose one way of putting that is that there's no reason that we have to have a simplistic acceptance or rejection of a particular philosopher; we don't put everyone in the good or bad column. What we do is we make distinctions between concepts that we find valuable in someone's work—pieces of analysis that we find valuable in someone's work—while being clear eyed about their actual vision for the world they wanted to see, and how if we do just sort of uncritically embrace their work, we are embracing something that might be very ugly. You point out that a lot of the uglier sides of Nietzsche's thought had been massaged by translation. You have an account in the book of your first encounters with him, where he feels like a bolt of lightning, and how it was so liberating to encounter this man's work because the first thing you encounter is not something that is obviously morally repugnant to you.

Tutt

Yes, that's right. Nietzsche said that no fresh idea was ever written sitting down. One of the things about being an intellectual, of course, is you need solitary time by yourself to study and figure things out, and Nietzsche speaks to the solitary soul in us. But he is also a thinker whose ideas literally jump off the page. So you read some Nietzsche, and you go on a hike; you read some Nietzsche, and you go off into the wilderness alone. You have a companion in Nietzsche. And so there's that spirituality. And the thing about the post-war translation, say, of Walter Kaufman, the most predominant translator of Nietzsche, is that he turned Nietzsche into an existentialist. They literally took all the self-help dimensions that I'm talking about here, and they said, this is the heart of Nietzsche. So part of what my book is trying to do is to remind folks on the left that actually there is a political side of Nietzsche, and that we can benefit from it by understanding its brutalism, but also understanding the depth by which Nietzsche actually thought politics, and the complexity by which he thought it.

Robinson

Well, I want to just conclude by discussing how you went through a transition from being influenced more by Nietzsche to being influenced more by Marx. Let us say that you encounter someone who has fallen under the spell of Nietzsche, but they’re not reading him critically in the way that you advocate in this book, and you want to say, no, there's a better way, a deeper body of thought—come and join the left. Maybe one way to do that would be to talk about your own transition towards a richer body of work that envisions a society that would actually be worth living in.

Tutt

What I would say, Nathan, is that if one wishes to get at the political core of Nietzsche, of course it's always important to read the core original texts, but again, Nietzsche's politics are beneath the surface. That's one of the interesting things about the esoteric dimension of his community building project. Everybody tends to have a favorite period of Nietzsche: the middle period, the late period. Everybody tends to have a favorite text of Nietzsche.

I think one of the most interesting political texts by Nietzsche is Human, All Too Human. It's written right at the moment in which Bismarck's Second Reich really becomes very Bonapartist, and Bonapartist is a term we get from Karl Marx’s Eighteenth Brumaire, which refers to this kind of fusion between liberal and socialist policy at a governmental level. Nietzsche is curiously very much in favor of Bismarck's anti-socialist laws. So if you read Human, All Too Human, it is peppered with advice. Nietzsche wrote many letters to heads of state throughout his career, and it's peppered with advice for how to maintain this anti-socialist compact at the state level.

If you read Thus Spoke Zarathustra, which is a text that Nietzsche considered kind of a poetic opera. It's a remarkable, highly creative and strange book. It's written in his later years, and it is his most aristocratic call for a kind of alternative community to the kind of mass socialistic community that's happening. So, Nietzsche's politics are apparent if you read him closely. What I would furthermore suggest is that there exists also a great lineage that's often forgotten in academic Nietzschean studies of Marxist critics of Nietzsche. The first is and the most important being György Lukács, the great Hungarian Marxist who wrote famously History and Class Consciousness, the philosopher who gave us this very important concept of reification. Well, he wrote a systematic rebuke of Nietzsche's politics and how his politics connect to his metaphysics, into his philosophy, in a work called The Destruction of Reason, written in the 1950s. That is a wonderful place to get a grasp on a Marxist critique of Nietzsche.

The other source I would recommend would be reading these thinkers like Kurt Eisner, and like Jack London, who we didn't mention, but I think, Nathan, you've written about Jack London yourself. Jack London was a very interesting kind of left-wing Nietzschean who put Marx very much first, but argued that Nietzsche could help activate class consciousness, and he's a thinker that emerges in early 20th century up through First World War period, and he became one of the main propagandists of Eugene Debs’s Socialist Party. His social writings, by Philip S. Foner, I would recommend that text. In the social writings of Jack London, you can see a very creative left-wing Nietzschean, actually. I would also recommend a wonderful political biography of Nietzsche that recently was translated into English in 2020 by Domenico Losurdo, an Italian Marxist historian. Here you will find the most thorough—it's 1000 pages, but it's very readable—and the most convincing case of the political core. Losurdo takes the esoteric politics and he makes them exoteric. That's what I would say.

But again, I feel the challenge of my book is that one can sort of have the spiritual—one of the things I would hate is that people walk away from my book and say, I don't want a spiritual uplift from Nietzsche anymore. No, I think things are more complex than that. I think that people can have the self-help feeling and vibe from Nietzsche, while also honoring the radical, brutalistic, anti-socialist, pro-aristocratic politics, and be careful of those and learn from them very carefully, and then I would hope maybe even form a kind of pugilistic relationship with Nietzsche, which is what I've grown to have with him.

Transcript edited by Patrick Farnsworth.