How the Soul of New York City is Vanishing

Jeremiah Moss on what neoliberalism has done to the culture and soul of New York City.

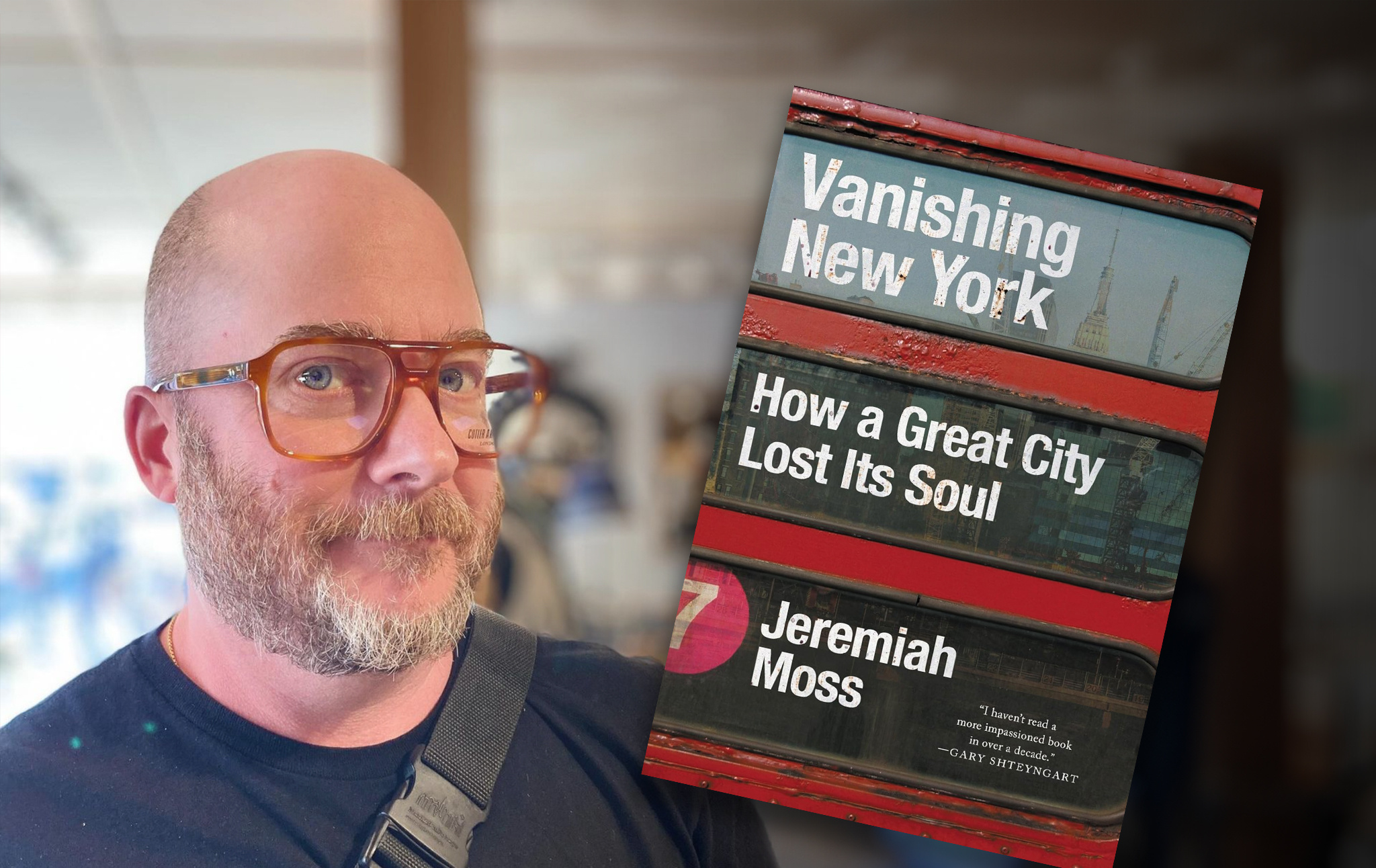

Jeremiah Moss (pseudonym of Griffin Hansbury) is the author of two books, Vanishing New York: How a Great City Lost Its Soul and Feral City: On Finding Liberation in Lockdown New York. Jeremiah's blog "Vanishing New York" has documented the disappearance of precious city institutions from delis to newsstands to theaters. Jeremiah's photography has previously appeared in Current Affairs. The New York Times, in its review of Moss's first book, says that "He begins no thought with 'on the other hand.' For Moss there is only one hand, and it is the hand of menacing greed and self-interest." You can see why he's our kind of guy. (The Times thought he was too hard on the rich, writing that "There is a case to be made that the enormously high price of living in New York (and Boston, and San Francisco) has had a positive ripple effect.")

Today Moss joins to explain what gives a city a soul and why he believes New York has lost a large piece of its own soul. He discusses what neoliberalism has done to culture and the effects of gentrification on beloved institutions. We discuss why "nostalgia" is actually healthy, why old, broken-down things can be good, and why people with money shouldn't be able to buy their way out of the inconvenience of living in a place with other people.

nathan j. Robinson

So, Jeremiah Moss is a pseudonym that you have written under for many years. Your blog, "Jeremiah’s Vanishing New York," attracted a lot of notice. How did the New York Times describe you? As some kind of curmudgeon? I think that was the number one word associated with you.

Jeremiah Moss

Yes, that word often came up a lot. It did.

Robinson

You wrote about the disappearance of a certain aspect of New York, a certain version of New York, and that's what we want to discuss today. Oh yes, "Curmudgeon with a penchant for apocalyptic bombast"—that's what I was looking for from the New York Times. I wanted to read that, and also the New York Daily News described you as a "fetishist for filth," which is also a wonderful description. Sorry, I had to find those because they're so good. But as I say, Jeremiah Moss is a pseudonym. So tell us a little more about who you are when you write as Jeremiah Moss.

Moss

I'm myself, certainly, but I think I'm occupying a part of myself. I'm also a psychoanalyst, and I think about, and talk to my patients about, multiplicity of self. We all have lots of parts, and sometimes we're occupying these parts depending on what context we're in. We all do it all the time. So Jeremiah was, and to some extent still is, a way to occupy that apocalyptic, bombastic part of me in a way that was emotionally freeing, and to just be in that part without having to worry too much about other parts that might complicate it.

Robinson

Of course, the name Jeremiah is a great biblical prophet name. So let me start with what I think is kind of an obvious question, which is the paradox of vanishing New York. Obviously, New York has not vanished. In one sense, you can still go to New York City. You can visit it. It's a city with millions of people. The streets are there. There are a lot of buildings there. There is a place on a map called New York City. It has not vanished, and yet it has. So, what do you mean when you talk about vanishing New York? What was the whole premise behind it?

Moss

I think of it as, everybody has their version of New York, the New York to which they're attached. The New York to which I am attached is the one that has served for a very long time as a space for outsiders to the American status quo, people who might be against the normative order of things. That New York City was a place where we could come, particularly neighborhoods like the East Village, Lower East Side, Greenwich village, Times Square area. These were pockets where we could come and find people like ourselves, people not like ourselves but occupying another position of outsiderness, and where there could be friction and happenstance, surprise and creativity, and ways of being that might be considered strange, negative, or dangerous to, again, the normativity of much of the world we live in.

Robinson

Tell us a little bit more specifically about what kinds of people you're talking about, and what it means for that to vanish. Describe a little more the tendency of disappearance that you're talking about. You describe certain people and phenomena in this book as “polar bears,” and when you spot someone who fits into the category that you mentioned, they're sort of like an endangered species at this point.

Moss

Well, it's interesting, because things have really changed since the pandemic. In my experience in lockdown New York from spring of 2020 through 2021, the polar bears came back during that time. New York City almost unvanished during lockdown, the New York that I'm talking about, and the streets, parks, the public spaces, really became filled again with people who were displaying queerness, and maybe street fashion became much more interesting. All that stuff is what really has been in many ways under attack.

So a lot of what I would write about on the blog "Vanishing New York" was about stores disappearing because of high rents and greedy landlords. People thought that it was a nostalgia project in some ways, but that's not really what I was trying to get across. It was really about how this is an ecosystem, and the storefronts, public spaces, and streets are all critical parts of that ecosystem that attract and enable a way of life. And that way of life also requires rents to be low. We need low rents for people who are more marginal to come in and occupy the space.

Robinson

One of the things I've always loved about the way that you write is, first, you help us articulate what seems inarticulable. A lot of people see these tendencies, experience these tendencies, feel distressed by these tendencies, but don't really know quite how to put into words what they're seeing. And you also give an explanation of why what is often dismissed as nostalgia is, in fact, a kind of rational response. If you're in a neighborhood, and the institutions that you love, the places that you frequent, the buildings that form your world, all the many different aspects that make up your world, start to be taken away piece by piece—you quote the term "root shock," which I rather liked, which is the feeling of distress that comes when you’re basically having the roots pulled up around you.

Moss

Exactly, which speaks to the "unnaturalness" of it. When I would talk about this with people, or when people would have a response to what I'm writing about, they would say, well, New York is always changing, that's just part of life. I use the climate crisis analogy, because even now, and certainly when I was writing the book, people would say the same thing: no, the climate's always changing, nothing's happening, or, it's a natural process rather than something that's being done, something that is part of extractive capitalism and how that works.

This is a project. The so-called gentrification of New York and many other cities like San Francisco is a project. It is planned. It is policy. It has an intent behind it. It's not just happening. It's not just a natural development that occurs over time with changing tastes or something like that.

Robinson

I want to get a little more into the structural causes of the tendencies that you are writing about. But first, I want to dwell a little more on the symptoms of what you're describing. There's a version of a story that occurs dozens of times over the course of this book. You describe a deli that's been there since 1904 or something like that. Interestingly and importantly, you mentioned earlier this romantic city of artists, poets, and outcasts, but it's also a city of immigrants and working-class people, and in many ways, this is a war on them. Family businesses have been there for generations and generations, and then all of a sudden, a developer comes in, buys the building, and the rent goes from $3,000 to $30,000 a month. Just ridiculous jumps, and there's absolutely no way that this business that has been there a hundred years can possibly survive. So, tell us a little more about the archetype of this story that has recurred hundreds or thousands of times across New York.

Moss

Yes, that was often the subject of the blog, that this was going on. It was like whiplash. Every day there'd be another one, another one. I think it really reached a peak in the Bloomberg years when I was writing the blog, where there was this just this rush. It almost felt as if these places were being targeted, and in some ways they are. I think older buildings get targeted for renovation. Again, I see a lot of it as a psychological hatred of the old. Maybe that's a very American or very Western kind of position, but anything that is old, that looks aged, that isn't keeping up with not only the present but the future has to be wiped out. And so, this would happen to buildings, to businesses, and to people. An older type of New Yorker also has to be wiped out, and that is the working class, the immigrant, as well as the queer and the creative. This kind of person is no longer welcome in this city and is very much being replaced. And we use the idea of settler colonialism: not just being removed but being replaced by a new, improved version of a human, a building, and a business.

Robinson

Yes, who are the new people? You talk at the beginning of Feral City about the new people.

Moss

Yes. So that's a tough one to write about, to grapple with this sense that there were these new people trickling in. And when I say new, I don't just mean new to New York. I mean a new kind of person, a neoliberalized self. This sense of walking around and thinking they're not quite human, they don't feel quite human. They're not engaging with other humans, and they all look exactly the same. Their ability to root out any sort of difference that would mark them as individuals is profound, to the point where they have the same skin, the same kind of buttery tan white person skin. It's the same tone. The clothing has no variation on a theme, even. It's got to be exactly the same.

I call them hypernormative, with this very intense need to conform to one another and to have this belonging. I'm fascinated by them. They operate almost by hive mind. I've noticed that it could be a 70-degree cloudy day, and they would not come out of their apartments. The sun has to be shining for them to come out. The weather, the temperature, everything has to be optimal for them to emerge, and then they emerge all at once.

Their behaviors—and I would hear this from people in different cities—would be the same from city to city. If they move into your building, they're going to behave just like the same kinds of people who came before and take up space in the same kind of way. They're going to sound the same. I'm obsessively fascinated by it.

Robinson

As you were talking about how the skin is the same, I was reminded of this passage in your book about your influencer neighbor’s decor, which I just want to read, because I think the aesthetic is interesting, too. Here she is giving a tour of her renovated apartment—this is on her video on Instagram or whatever. "Behind my crummy kitchen with its broken stove and leaky sink, I look for books painting some sign of a creative and uncontrolled life, conflict and imperfection, but there is nothing. She has one green plant, a housewarming gift from the landlord. Everything else is white. The couch is white. The pillows are white. The curtains are white. The bedsheets and blankets are white. The desk is white. The dining set is white. The rug is white. The new mirror, the one that replaced the old white mirror, has a blonde wood frame that looks almost white. The influencer loves the blonde wood because she says everything's white, so I needed, like, some texture."

Moss

Yes.

Robinson

What's with that?

Moss

What's with that? I know it's a trend: the white trend. I also read white supremacy into it. There's also something about purity and cleanliness: what white represents. The white shoes—this is also another thing that makes them crazy. They all wear these white sneakers that never have a blemish. It looks as if the soles have never touched the ground. And this is New York City—you're walking through vomit and dog shit and all kinds of filth, yet these shoes are never blemished. And I think that that's part of it. This sort of streamlined look that indicates I've never been touched by anything. Nothing can get to me. That is a sort of hermetically sealed way of going through the world, and I think that that's very much part of what they're doing. They are not interested in being New Yorkers.

Oftentimes, they'll talk about actually disliking the city, disliking the things of the city. They want to bring the suburbs to the city—the suburbs as a place of safety from the disorder of the world. Everything manicured and fortressed. And they are—in themselves, in their bodies— little fortresses going down the sidewalk.

Robinson

Can I ask you to elaborate on a phrase you used earlier, “the neoliberalization of the self”? You also use the phrase “the neoliberal psyche” here. We've described a certain aesthetic, a certain way of going through the world, trying to seal yourself off from the mess. You've talked about conformity, but listeners might wonder, well, how does that relate to neoliberalism?

Moss

So, neoliberalism is policy and economics, but I think it also has this psychic piece as well. You could think about the neoliberalization of the mind as a way of influencing how people think and how people think about themselves as humans amongst other humans in the world. Neoliberalism encourages all of us to turn ourselves into products so that people can then identify with other product. They identify with their MacBook, they identify with their Coca-Cola, whatever it might be. And if you've ever criticized a product in front of one of these people, they'll become extremely defensive, and they will often defend and protect that product very angrily. To me, that indicates that there's been some sort of enmeshment with the product world.

Social media, of course, enhances this. We brand. We become brands. Influencers certainly do this. Something that blows my mind is the way that people will—I don't know what they're called. There's “advertainment,” or some kind of word for this stuff. A brand will pop up in a public space, and you line up to take your picture with these Instagrammable brand moments or something. How easy it is to get people to advertise for free and provide advertising for corporations. That, to me, is a mind that's been neoliberalized. It is one with capitalism. It has no critique of capitalism, and a lot of people will de-subjectify or dehumanize themselves in order to make space internally for that way of experiencing themselves as a dehumanized product.

Robinson

You talk about how New York City leaders have also tried to turn the city into a marketable product. You have a whole chapter called Gloomberg, and Michael Bloomberg himself said, essentially, the goal is to create value. He said, what I've tried to do is create value for developers every single day of my time. You talked about a different way of conceiving of the self, and that same way is mirrored in how you can conceive of the city.

Moss

Exactly. And Bloomberg also said, New York City is a luxury product. So it was very much a construction, if you will. The stage was sort of set prior to that—I think that Rudy Giuliani played a really big role. He came in as the cop who beefed up policing and brought in broken windows policing, the idea that at any sign of social disorder should equate in people's minds with violence, so you have to remove it. So, graffiti means there's going to be murder, and so you get rid of the graffiti, and somehow you don't have murder. That's not really how it works. It's been debunked, but that's what Giuliani did.

The "quality-of-life" campaign was another one of his policing strategies. So Giuliani came in and “cleaned things up.” And then under Bloomberg’s reign, it was really the pinnacle of the neoliberal city. He was very much about turning the city into a glittering playground for the very wealthy. He said numerous times he'd want to get every—I think he said—Russian oligarch billionaire to come to New York. He was very unabashed about that. And that kind of city is not meant for everybody. It's not meant for the working class, the immigrants, struggling artists, young queer people, people starting out. It's certainly not for people who are homeless. It's not for the poor. It's very much for the very wealthy, and a lot of them are the people that I'm talking about, the new people.

Robinson

You're talking about how there's even been war made against hot dog vendors on the street. But these are the people who make your city what it is. People love the hot dog vendors, but they, too, are part of the mess that must be cleared away.

Moss

Right. We had all these lovely old newsstands, and they were made of wood and were all really idiosyncratic. They were owned by the newsstand person, and some of them were painted red or green or blue, and they were decorated and done however the person wanted to do it. This offended the Bloomberg sense of order. They were too messy, so he basically got rid of them and essentially stole them from their owners and made them all install these glass and steely-looking boxes that are all the same and that look exactly like the condo buildings that were being built, the same aesthetic.

So the people who own the newsstands then had to rent the newsstands from a corporation that Bloomberg made a deal with to run the newsstands. He wanted everything streamlined and the same, like all that whiteness—perfect, pure white sneakers that don't ever get a smudge of dirt on them. This is the kind of aesthetic that he brought into the city, and there's a lot of fear in that, a fear of contamination. And so you can have the germophobic part of that as well as the fear of difference. To me, a city is a place we're supposed to rub up against each other, rub up against difference, and be changed by it. We're supposed to get contaminated. You come to the city to be contaminated by it. That's what it's for. It's not to be kept out.

Robinson

There's also this kind of belief that if you have money, you should be able to buy your way out of any inconvenience. And the city that you're talking about, we have to be honest, imposes inconvenience on people. Some of the people that you're talking about are difficult to live with. Some of them are going to be obnoxious. You're not going to get everything you want. It's going to be hard to live with other people. Some things are going to smell bad sometimes, and you're not going to be able to just call someone and say, can you have the police carry away the smelly thing, this thing that I don't like, this thing that is a burden on me? People will complain about the city that you're defending as a place that has dirt and noise and grime and say these are bad things that need to be carried away, but you're talking about the way we have to develop a tolerance for one another and a willingness to accept difference and outsiderness.

Moss

I can complain about absolutely everything. It’s a New Yorker’s birthright, and we should complain about all these things, but the expectation that it shouldn't be there is something else. I think it mirrors a kind of internalized capitalism, this internalized neoliberalism, the idea that we should somehow be above the human condition of you can't get what you want. And so, I bring in the idea of queer negativity. I was just reading a book called [Negativity in Psychoanalysis], which really is against the idea of cure. So, cure is, in many ways, a capitalist idea: you can always improve, you can always get better. But you can't, actually. The work, to me, of psychoanalysis is getting to a place where you can live with the fact that you're in a body that's dying. There is chaos and disorder, and you can't control it. You're going to be gone one day, you can't have what you want, you can't have the perfect love, and you can't have the perfect whatever. These are illusions. I think that that illusion gets sold because it makes money.

Robinson

One thing in New York that's been really harrowing is the cab driver suicides, what happened to New York cabbies in the age of Uber. Uber and Lyft are premised on the idea that you shouldn't ever have to have a grumpy cab driver. If you have a grumpy cab driver, you can just give them a bad review—they've got no stars, and then they'll get fired. And that's what happens to a grumpy cab driver. The New York that you're defending is full of grumpy cab drivers.

Moss

And the grumpy person—you referred to how I was called a curmudgeon—is a problem for people. They don't want that. But the grumpiness was part of what attracted me to New York. There was a great restaurant—quasi-restaurant—called Manganaro's in Hell's Kitchen, and two Italian American women ran it, and they were really grumpy. You'd walk in, and it was like walking into their kitchen. They'd be hanging out—there was a table in the back where they made food, and if you had a question, they'd be like, hurry up and order already. I love that. I grew up in a working-class Italian American household, so that, to me, was like being at home. I get that there's also this Midwest kind of passive-aggressive thing that's coming to New York. New York used to just be aggressive-aggressive.

Robinson

Because they're not nice. It's not that they've replaced being a curmudgeon with being really kind.

Moss

No, they're not. They’re actually quite violent, in a lot of ways. But with the old grumpy thing, you knew what you were getting. It was Italian, Jewish, sort of working class—that wave of immigration as well as others—but that's not permitted anymore, and so these people get pushed out. And with Manganaro's, what would happen is a lot of people would go in there and would write Yelp reviews and absolutely slam them.

Robinson

I was going to say, those women have two stars on Yelp.

Moss

And they were like, fuck it, I'm out, and they closed up. They couldn't handle the aggression anymore—the passive-aggression, really. Kim's Video was a notorious place: you'd go in, and you'd be terrified to rent some crappy little rom-com or something because they’d sneer at you or pretend they didn't know where it was, and you'd be judged. But that's part of the excitement and the thrill and the culture of being in New York.

Robinson

It makes life interesting. To live an interesting life where things happen to you that you don't expect, and they're not all good.

Moss

Exactly, and you get that feeling about it.

Robinson

Anger is one of those feelings, frustration is one of those feelings.

Moss

But you're alive.

Robinson

You're alive. You don't know what's special about things, sometimes, until they get taken away from you. You don't miss your water until your well runs dry. I had a tiny exposure to your vanishing New York. I'm not from New York, and I’ve spent about six days in New York over the course of my entire life. But one time I went to New York, and I'd heard that there was a wonderful accordion store, a place called Music Row. And so I went to it, and it was a magical place. I played the accordion when I was in middle school, so it was so cool to me to go to that place. But I didn't think much of it. I was just like, oh, there's an accordion store. A few years later, I see the end of Music Row. It’s all gone, turned into luxury development. The old man who ran the accordion stores said, we can't make it anymore, the rent is crazy high. I thought, I saw that, and no one else will ever see that. It's gone now. It has vanished, and they won't have any idea. And it did not touch me that that was even a special experience until I knew that nobody else could ever have it.

Moss

Right. That was a wonderful place, and you could stumble into it, and again, have that sense of surprise. What you said reminds me of another criticism that I would get about the blog, which was, why do you care about that place? Did you ever go there? And my response to that is, so I should only care about what was relevant to me? I shouldn't care about anybody else or their experiences? That's an anti-community attitude. Nobody else matters except for me, the individual. But all those places are important. They're all part of the fabric, the ecosystem of the city. We're talking about New York, but this is a global problem.

Robinson

I want to raise a couple of points that I'm sure you have gotten in response. You write in the book at one point quite fondly about a pretty crummy Howard Johnson's in Times Square. I understand how you could care about the cannoli that's been made the same way since 1902, but how can you have feelings about a crummy Howard Johnson's in Times Square? And you also write about, I think, your apartment building at one point. What's interesting is that it's not a beautiful old building that has all this exquisite masonry that's being torn down. It's falling into bits. There's a lot of stuff that you talk about where people will say, no, that's just objectively not great. So, how can you defend those things or argue that they shouldn't be replaced or upgraded?

Moss

I’m attracted to the crummy. I'm trans, and in Feral City, one of the things that I conclude is that there's something about my transness, my queerness, that identifies with the crummy in terms of it being outside of and against. In the crumminess and in the crumbling, it is standing, in some ways, in resistance to the prettification and the normativity that is being coerced from the outside. So, for people who are more marginal, the people who want to correct us, who people want to fix us, they might want to fix that Howard Johnson’s, they might want to fix that building. They fix the city in a way that makes it all clean and “nice.” And so, I'm with the people who are resisting being fixed.

Back to that idea of cure and the ways in which capitalism and normativity work through the cure, the fix is to make everything streamlined and take away the humanity that's in it. When I look at a crumbling building, to me, it has a humanity to it. It has a kind of texture and softness. It's like the Japanese idea of wabi-sabi, that an object is made more beautiful because it has a crack in it. I don't find a glass box to be beautiful in any way. I find it to be an aesthetic affront.

Robinson

We recently published an article called "In Defense of Graffiti,." You can tell a lot about a person by what they think about graffiti: are they amazed by it and see it as an incredible, vibrant expression of all these people with their individual messages and styles making their mark on the city? It's so interesting. Do you think a subway car is better or worse for having graffiti on it?

Moss

I love graffiti. It was really almost wiped out prior to the pandemic, and then when the lockdown started, graffiti just blossomed. We are in a renaissance of graffiti in New York City, and what I find so exciting about so much of it is that you can see that it's not being done by people who are really practiced at graffiti. It’s really shitty graffiti. It's like some sloppy kid with a can of paint or a magic marker or something. In 2020 and 2021, a lot of it was very political. A lot of it was poetic. A lot of it was text based. And at that time, all the advertising, those ad posters that go up on the boards and walls everywhere, had stopped completely, and so walls remained available to use completely. And then, of course, there were more wooden boards because in the George Floyd uprising, the windows of Soho and other places were smashed and people put up these protective boards, and those got covered with graffiti and art and incredible messaging. Suddenly it was like, oh my god, you can hear the streets again. You can hear what people are thinking about and what feels urgent to people. There's a communication happening there. That underground current that got covered up and smashed came back to life. It was just such an incredible experience. So, I love graffiti. On my Instagram page, I'm constantly taking pictures of what people have to say, what the streets have to say. Today I go out and look for it. It's beautiful.

Robinson

Let me ask you how we can think about an alternative and healthy conception of change and progress. One criticism is related to what I've said of your point of view, that you are romanticizing things that, in many ways, something should really be done about. Violent crime: no, we don't like violent crime. People look back on 1970s New York and murder. The murder rate in New York has dropped a lot, and we don't want people to be murdered. And there are also difficult cases, like how New Yorkers love the Pizza Rat. I have a friend who loves the Pizza Rat so much she did a song about the Pizza Rat. I find having a subway full of rats to be a little disturbing. I can't tell whether that's a good, romantic part of a city or whether that's a part of a city that's a problem that needs to be fixed, that we shouldn't romanticize the proliferation of vermin. Do you want to fix the subways, or do you like the fact that they don't work very well? So, how do you think about what kinds of improvements and changes should be made?

Moss

Right. I think when we talk about progress, we're often talking about a kind of capitalistic idea of progress: growth. It's always about growth, and we know that growth is destroying the planet. But god forbid anybody should say, maybe things shouldn't grow so much. Like cancer: maybe cancer shouldn't keep growing. I'm going back again to 2020, when there was this incredible progress that emerged. In things like mutual aid, we suddenly had community refrigerators on the corners of the streets in our neighborhoods, where anybody could put food into the fridge and anybody could take food out. They're slowly disappearing. We had free stores. Same thing in the abandoned storefronts. People put up shelving and signage, and anybody could leave anything, and anybody could take anything.

A group that I was involved with established a mutual aid every Friday night in Washington Square Park, bringing food, clothing, and community and connecting with other people who needed whatever there was to offer. The other phenomenon, and it's impossible to measure, but it was something that I witnessed, was that the homeless folks were really left alone in the pandemic and were not harassed by police and were much more visible on the streets. And because we were in this moment of ambient death and sickness and anxiety, and because the streets had quieted down in this very particular way, people who were not homeless were coming out and engaging with homeless people, talking with them, getting to know their names, bringing them food and clothing, and nobody was harassing them and making them invisible. And so people who were psychotic were very calm. As soon as lockdown ended and the city reopened and the new people came back, you saw that psychosis turn much more towards the aggressive and the frightening.

We have to ask, why does that happen? To me, it's quite obvious. Treat humans like humans, and they'll be more chill. It's not complicated. To me, progress means taking care of people. That's it. It doesn't mean building more condos and putting in more upscale restaurants. It means taking care of people. But a lot of people don't see that as progress. It doesn't make anybody rich.

Robinson

You've covered so many changes in New York over the course of doing "Vanishing New York" and writing a couple of books. Is there one thing that you really just can't stand? Just let your full Jeremiah Moss out—the thing you hate when you're at your most Jeremiah. And then tell us one thing you really, truly miss, that was beautiful, and that you think about a lot.

Moss

I'll talk about Washington Square Park, on both sides of that coin. Washington Square Park became very policed and controlled in the Bloomberg years, and in the pandemic lockdown, it really came back to life. It became an incredibly diverse, joyful place in the pandemic. We were having dance parties, and there was music in every corner of the park. It was no longer an almost all white space, which it had been prior. It was the most beautiful place I'd ever been.

And now it has reverted back to what it was. It has been violently policed in order to become a whitewashed space where the only music allowed is this calming sort of jazz for the tourists. Every time I go in there, I'm in a rage, basically, because I know what it used to be, and I know what it should be, and I know the violence that is used in order to make it what it is. And I was in that violence. I was in those protests and riots, and I saw my friends get hit in the head by police and dragged off and arrested because they weren't the right kind of person to be there. And every time I go into that park and I see the people who were there, taking pictures of the arch, all I can see is the violence that was used to make them comfortable.

Transcript edited by Patrick Farnsworth.