The Shifting Discourse on Israel, Zionism, and Jewish Identity

Peter Beinart discusses how narratives of Jewish identity impact understanding of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, parallels between Zionism and colonialism, and lessons we can take from the end of South African apartheid.

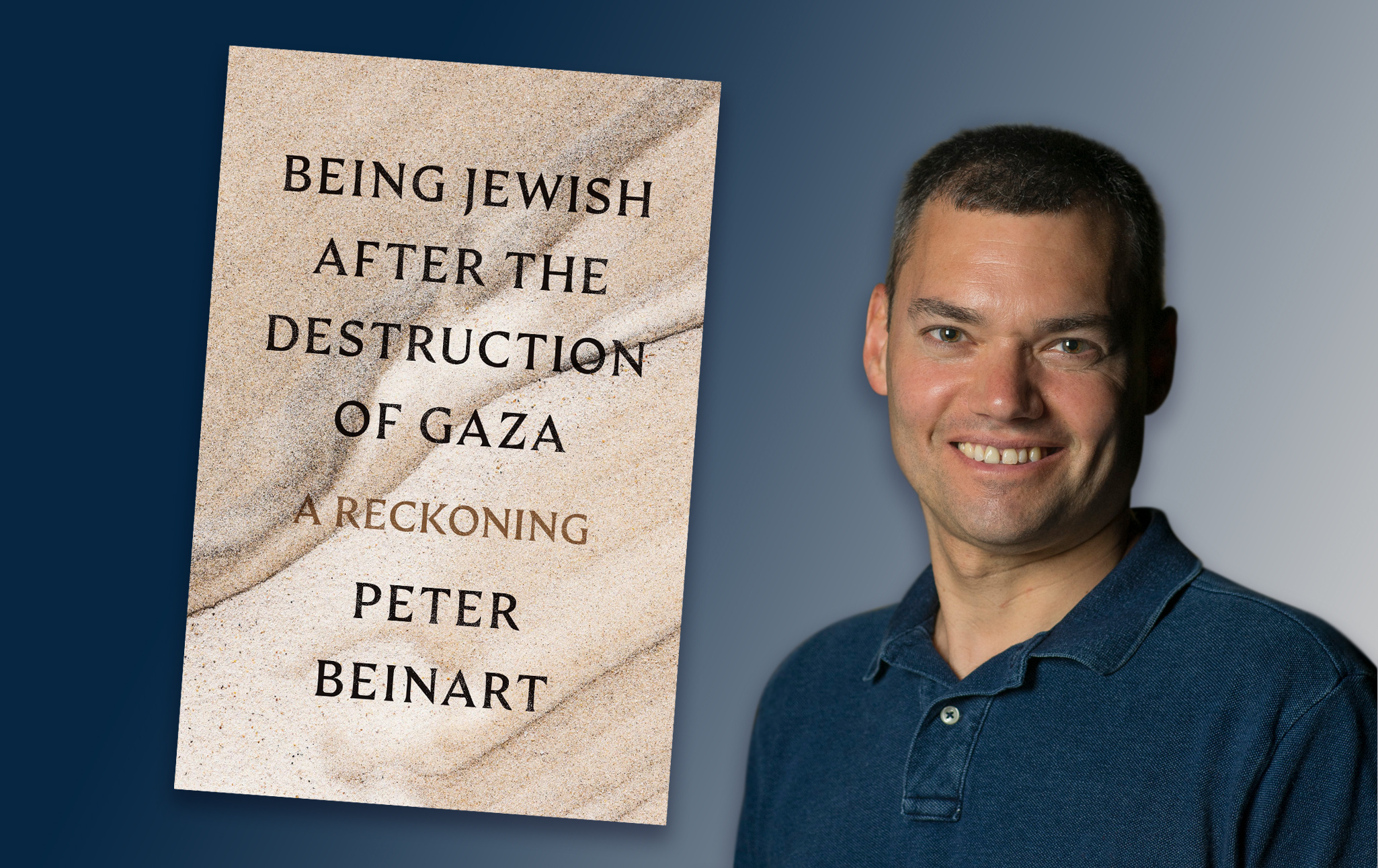

Peter Beinart is a distinguished journalist, political scientist, and editor-at-large at Jewish Currents. He joins today to discuss his latest book, Being Jewish After the Destruction of Gaza: A Reckoning, and the shifting discourse on Israel, Zionism, and Jewish identity. Beinart reflects on his own ideological transformation, the narratives that shape Jewish perceptions of Palestinian resistance, and why Israeli policy ultimately makes Jews less safe. He also explores the historical parallels between Zionism and colonialism, the suppression of Palestinian resistance, and what lessons can be drawn from the end of South African apartheid.

Nathan J. Robinson

It is safe to say at this point that much of your writing career, much of your published work, is about changing your mind on things, whether it's the war in Iraq or whether it's about contemporary Zionism. If you look back at the Peter Beinart who worked at The New Republic under Marty Peretz, for example, can you tell us how that Peter Beinart, someone who still held the original views that you may have held about Israel, would have interpreted the destruction of Gaza?

Peter Beinart

Well, the truth is that at that time in my career, I wasn't writing very much about Israel at all. It wasn't the focus of my writing until after I left The New Republic. And honestly, I can hardly exactly imagine even how The New Republic itself, the institution, would have responded. It was a very different moment. But I think that my evolution on this question really began as I started spending time in the West Bank with Palestinians, reading more Palestinian writing, and thinking more about what Israel or Zionism meant from the standpoint of its victims. And there are plenty of things in the 1990s that I believed and still believe, [...] but on this particular topic, I have changed very profoundly.

Robinson

One of the things that comes across in your book is that you are in many ways dissenting from and in conflict with the views of many other Jewish people on Israel-Palestine. You begin your book with a letter to a former friend who would now very much disagree with you on this topic. Lay out the perspective that they hold and that you are responding to in this book.

Beinart

Sure. I think the perspective is that the world is a merciless and brutal place, and if you don't have a state that you control, that you rule, you are likely to be in grave jeopardy. That's the interpretation of Jewish history that many Jews around the world hold. And so from that perspective, even if you are inclined to admit that Israel is doing things that are not particularly nice to the Palestinians, you believe that it’s the ultimate bedrock of Jewish safety.

Robinson

It seems like what you're arguing here is that, in many ways, Jewish history, storytelling, and mythology has ended up coloring perceptions of the contemporary world for many Jewish people in a way that distorts their understanding of what is actually going on with Palestinians, how Palestinians feel, and what their actual motivations are.

Beinart

Yes. I think there is a tendency to see Palestinians and the conflict between Palestinians in Israel in a certain template. [...] [It's a] narrative [that says] that in every generation an enemy rises to destroy it and that that enemy is motivated by some kind of perhaps inherent desire to destroy and kill and subjugate Jews, rather than understanding Palestinian responses to Israel and Zionism—not all of which I would always agree with, by the way—as a response to dispossession and oppression.

Robinson

It’s not totally unreasonable to have a story that in every generation an enemy rises to try to destroy the Jewish people given the history—not just the Holocaust but the history of pogroms. You go back to the Purim story, which is at the center of what you tell here, which is a story that I think many non-Jews like myself might not necessarily be familiar with. It’s a story of a genocide that is ordered, and they have to stop it by killing a very large number of people.

Beinart

Yes, in fact, we’re speaking literally on the day of Purim itself, where you can read the Book of Esther that tells that story. So yes, the challenge that I was wrestling with in the book is that, I think all of us who want to be critical of not just what Israel is doing in Gaza but critical of the entire idea of Jewish supremacy, need to balance that criticism, that moral position—which is fundamentally important—with some empathy for these kinds of experiences that would have led many Jews—not all, but many Jews—to see the world in this way.

Robinson

You hear very much in the rhetoric of Israeli politicians, “Hamas are Nazis” or even “Palestinians are Nazis.” Constantly, it's “they want to throw the Jews into the sea. They want to wipe out Israel. If we do not act, we will be destroyed.” This is the narrative. And thus, from the right to the more liberal Zionist perspective, you often hear this—and the liberal Zionist perspective is, yes, the destruction is a tragedy, but, sadly, the destruction of Gaza is a necessity because that's what happens when you are facing an existential threat. As in the Purim story, you must do things that are unpleasant but necessary for survival.

Beinart

Yes. My book is an argument against that, not only as a moral argument but also an argument for Jewish self-interest. Because I do care very deeply about Jewish safety, about the safety of my people, and just at a kind of child-like level, I think there's a fundamental flaw in thinking that you can make yourself safe by making the people who live next door to you radically unsafe. That system of violence which has now reached apocalyptic proportions in Gaza produces violent resistance. That doesn't justify things like targeting civilians, as what was done on October 7, but the truth is that that system of violence is likely to make everybody less safe.

Robinson

What's the Auden line that you quote that about this? You'll remember it.

Beinart

I think the line is, "to those whom evil is done, do evil in return."

Robinson

Which is valuable both as a caution to Israelis about avoiding this narrative of perpetual victim[hood]—those who fled and survived the Holocaust definitely had evil done to them—and is crucial to understanding the Palestinian reaction to the Israeli occupation. At one point, you profile a Palestinian who hated Hamas, despised Hamas in his bones, and then after so much violence, finally tips to the point of, well, now I support armed resistance.

Beinart

Yes, absolutely. This is a human response. And this is part of why I argue in my book that the more revolted and upset you are about the targeting and kidnapping of civilians on October 7, the more emphatically you need to support Palestinian resistance that's ethical, by which I mean that conforms to international law, whether boycotting, sanctions, nonviolent marches, going to the international criminal court, or even violence that respects the laws—the norms of international law.

Ukrainians have the right to fight Russian soldiers but not Russian civilians. And the same thing goes to Palestinians who are having their land seized by Israeli soldiers. But I think the problem is that the mainstream American Jewish community and most American politicians simultaneously condemn Palestinian armed resistance against civilians and fight fiercely against any other form of Palestinian resistance, even when those other forms of Palestinian resistance don't threaten the lives of Israeli civilians.

Robinson

Yes. You highlight things like, for example, the Israeli response to the 2018 Gaza Great March of Return, which was a largely peaceful protest in which Palestinians did follow the kind of Gandhian path of, well, what are you going to do? Well, they marched. They decided to march to the wall and tried to symbolically cross over. And the Israeli response was to get out snipers and shoot them, some in the legs, but some not in the legs. Two hundred people were shot to death.

Beinart

Right. And the way it was depicted was, well, maybe they're marching nonviolently, but they want to leave Gaza and return to the land they're from, and that is inherently a threat, even if they're not harmed. Just the idea that they may want to go back to the land from which their parents or grandparents were expelled inherently makes them a threat. And that's the problem with the entire discourse, which is based on the idea of Jewish supremacy. It’s the notion that Palestinians would want things that in other contexts would be seen as entirely legitimate and normal. To be able to return to lands from which you were violently expelled can only be understood as an existential threat to Jews.

Robinson

You point out how language is used, so that phrases like “the right to exist” are used to suggest that, unless Israel is maintained as an explicitly Jewish state, Israel no longer exists, and it's sort of implied that Jewish people in the land of Israel no longer exist. To fight against Israel as a Jewish supremacist state is conflated with genocide.

Beinart

Yes, absolutely. [...] States don't have unconditional value. They are merely instruments for the protection of human life. One should start in evaluating any state with the human beings who live under its control—Palestinians and Jews—and ask whether the state is doing a good job of protecting their lives and allowing them to flourish. And if it isn’t, you think about a different kind of state that might do a better job. The human right to exist is what is unconditional, not a particular state form, especially one in this case that is built on the legal supremacy of one group over another.

Robinson

Do you think that the concept of Zionism is inherently defensible? There are plenty of people who say Zionism is inherently wrong. And I suppose your answer is probably going to be something like, it depends on what we mean by the term.

Beinart

Yes. Until 1948 there were forms of Zionism, sometimes called cultural Zionism, that did not believe in a Jewish state. That's kind of weird for people to hear now because now Zionism is a Jewish state. Noam Chomsky, as a very young person, was a member of a Zionist youth group that opposed the creation of a Jewish state. That was the position of Martin Buber. So there was a form of Zionism that meant Jewish cultural flourishing in historic Palestine. That form of Zionism, I don't think, is inherently oppressive because it’s compatible with equality under the law. But the Zionism that actually emerged in the state form, the ideology of the state in 1948, is built on this legal supremacy of Jews and therefore is an inherent contradiction to the principles of liberal democracy.

Robinson

Now, you've gone back to 1948. One of the other points that you make in your book is that early in the history of Zionism, the rhetoric was often explicitly colonial. There is now an effort to suggest that Israel is acting defensively against aggressors. But actually the language of Jabotinsky, for instance, who was kind of the intellectual forebear of Netanyahu, was that, no, we're the settlers, they're the Indians—essentially the equivalent of the American Indians—and we're going to hold them off.

Beinart

Yes, because colonialism was not a dirty word at that time. Many Jews and others get upset now because if you suggest that Israel or Zionism has these colonial features, you're denying that Jews have a connection to the land. But Jabotinsky was certainly aware that Jews pray facing Jerusalem and that our liturgy is filled with references to what we call [...] the land of Israel. But he didn't see that as a contradiction to the idea that this is also a movement led by Europeans who, like non-Jewish Europeans, had a certain attitude towards these parts of the world beyond Europe, which they saw as backward, and they saw themselves bringing modernity and progress. They believed that they had the right to dominate the people who were there [and to do so] in the name of modernity and progress, and it didn’t work out very well for the people who came under that colonial rule. So it was a much more frank discourse, in a lot of ways, than what we hear now.

Robinson

Well, there are still Israelis you cite, for instance, the historian Benny Morris, who's almost an embarrassment because he's very frank. He says, no, Ben-Gurion wanted to transfer the Arabs, and that was a good thing [because] they needed to be expelled. And ethnic cleansing isn't always bad. That's like a direct quote from Benny Morris: sometimes you have to ethnically cleanse some people. [...]

In your book, you talk about the story of Purim, and one of the things that you do so well is to excavate parts of Jewish history and of biblical teaching and stories that you think need to be recognized and grappled with. One of the things that you talk about is the obscuring of the Book of Joshua. Maybe you could mention that and how that fits uncomfortably into certain narratives.

Beinart

Sure. You're maybe the only person who's asked me that question, so I appreciate it. The point I'm trying to make is that in claiming Jewish indigeneity to the land, the American Jewish organizations will often say that there were these ancient Jewish kingdoms there, which was true. But what they don't acknowledge is that, according to the Hebrew Bible itself, these were the product of a [conflict]. Now again, whether there ever was such a person named Joshua, what he actually did—again, this is not history, it is a sacred text. But the point I'm trying to make is that when contemporary Jewish leaders talk today, they excise out those elements of our own tradition that talk about conquest in the same way that they avoid how Israeli actions today might be morally problematic. [This creates] what I call a kind of virtuous victim story.

Robinson

I think a lot of people probably feel deeply hopeless and pessimistic about the future of the Israel-Palestine conflict right now. The destruction of Gaza has been hideous. By some estimates, over 100,000 lives have been lost. Trump is talking about the full ethnic cleansing of Gaza. We really don't know the future of the conflict. However, in the book you mention the example of South Africa, where you have a family background. Obviously, South Africa isn't perfect today, but you do talk about it as an example of a place where the same kinds of stories were told and where they eventually came to be seen as ridiculous, and apartheid did, in fact, eventually crumble. So what is a potential vision for a conclusion to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in the long run?

Beinart

Yes. We don't know how history will turn out. And you're right. Right now, it looks extremely bleak, but there are moments to point to in the past where great moral movements have made things that seemed impossible at one point become possible. I know from personal experience. In the 1980s it was impossible for white South Africans to imagine that there would be a Black government, and indeed that they would be safe under one, and yet it came to pass, just as many Americans in the first half of the 20th century could never imagine a U.S. military where white soldiers took orders from Black officers, but the civil rights movement made that come to pass. So the question is, can there be a movement on behalf of Palestinian freedom that matches the kind of power that can make the impossible possible? We don't know, but I think the imperative is for us to do whatever we can to help bring that about.

Transcript edited by Patrick Farnsworth.