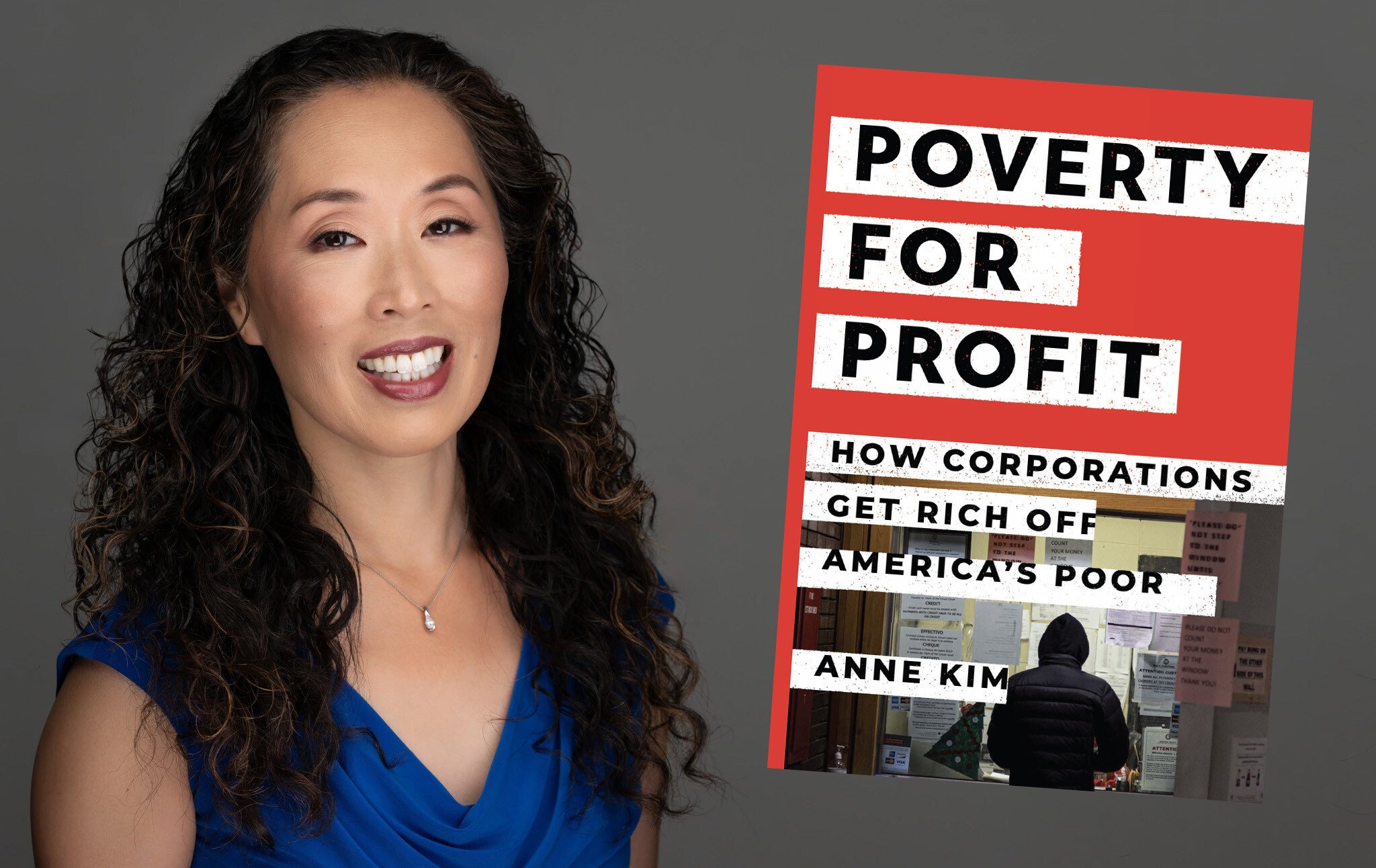

How Corporations Profit Off Poverty

Policy journalist Anne Kim on how the welfare state is sucked dry by parasitic for-profit companies.

Anne Kim's book Poverty For Profit: How Corporations Get Rich Off America's Poor gives a partial answer to an enduring question: how come we spend so much trying to solve poverty but poverty persists? One major reason, Kim argues, is that parasitic for-profit industries suck a lot of the money out of antipoverty programs. The privatization of government functions has meant that plenty of money that should be going to the least well-off ends up padding the pockets of the already wealthy. Kim's book helps us understand why, for example, cities can spend so much trying to combat homelessness and not seem to actually do much to alleviate it. Kim shows us how our tax dollars get siphoned away, and lays out a blueprint for how we might use government far more effectively, if we abandon the mindset that privatization means "efficiency."

Robinson

I suppose the first question here is, how is it possible to make a profit from poverty? Poor people don't have much money. That's the nature of being in poverty. So how is there money to be made off the poor?

Kim

Well, the government has money, and the federal government spends at least $900 billion a year—that's an underestimate, actually—on programs for the poor, and over the last 40 to 50 years, there has been a steady privatization of social services. So, that is government money that is going to private corporations to deliver social services, and then there is a lot of profit taking from poor people themselves, in the form of skimming off the benefits that low-income Americans receive from the federal government.

Robinson

Your book kind of surprised me. When I'd think about profiting off poverty, my first thought was just pure private industry, like payday lending. But then, you point out that, actually, we don't really think correctly about the way that anti-poverty programs work. You point out that we have this kind of binary thinking, where the Right says we need less funding for anti-poverty programs, and we need personal responsibility, and progressives say, no, we need more generous funding for anti-poverty programs. You say that that binary actually misleads us about what is going on with the funding of anti-poverty programs. Tell us what you mean by that.

Kim

The debate over poverty, at least in the United States, is kind of stuck in the binary you're talking about, and part of that is because we spend a huge amount of money on anti-poverty programs, but the poverty rate hasn't moved. In 2023, the poverty rate was about 11.5%, which was basically the same as it was in 1977, so both sides look at that number and say, what's going on? and these are the two kinds of leading explanations for what's happened in this very polarized debate we have just about everything. What I'm positing in this book is that there's something else that's going on here that is making federal and state anti-poverty programs a lot less efficient than they could be, and that accounts for some portion of the reason that poverty has been so persistent over the past 50 years. That is because this infrastructure of poverty has arisen that is dependent upon poverty and upon poverty programs to survive, and that, I think, is a significant drag on the effectiveness of anti-poverty programs and the efficiency of government spending. If we could tackle this problem that's been hidden for so many decades, perhaps we can make some progress on reducing poverty for real.

Robinson

I was saying there is a common conservative argument that will look at that huge amount of money spent on poverty and the stubbornness of the poverty rate, and will say, we are wasting all of this money, and clearly, poverty is just a matter of choice. And also, your book helps illuminate something that has just frustrated me for so long and always wanted to know the answer to, which is that I'm constantly reading stories that you sometimes hear from the Right, that California spent so much on homelessness, and there's still so many homeless people. When I read that, I think to myself, where on earth is the money going? They say, you see, some cities spent this much per homeless person, and they built this few houses. And you wonder, where is the money going? What is actually happening here? And so, you dive in and go down to the ground level and try to answer this. So, tell us, where is the money going?

Kim

Well, it's going to the company that's supposed to be building the affordable housing or delivering job training or whatever. What I'm talking about here in large part is this colossal failure of governance, this money sluicing through the system for which there is not enough oversight and accountability for what is happening with these dollars. It is the result of this wave of privatization that began in the 1980s with Ronald Reagan. There was an ideological shift between government versus the private sector. Ronald Reagan famously said, government is not the solution, government is the problem, and he convened two commissions in 1984 and 1988 to discuss different ways in which the private sector can take over government. That's what's happened. But guess what? The private sector is actually not doing a good job compared to possibly what government could be doing, and that is what we're seeing when we see all these dollars going to homelessness or what have you. It's not necessarily going to the actors who are acting in the best interests of the people who are to be served, but perhaps acting in their own interests, and they may be acting without a lot of oversight. So, the leaky bucket is extremely leaky. Let's put it that way.

Robinson

Yes, the argument would be that the private sector is more efficient than the government, but another thing we learn from basic economics is that people and corporations respond to incentives, and if there is a bunch of free government money to be handed out, there are going to arise companies who do everything possible to get as much money of that free government money as they can, while delivering as little in return for it as possible. And you point out that in many different parts of the system, that's precisely what is happening: companies arise that do very well pocketing as much as they can and giving back as little as they can in return.

Kim

That's right. I think the private sector is efficient when you have the right incentives in place, and you have competition. And this latter point is very important because when you're talking about social services, what exactly does that market look like? There really isn't one. Just to back up a little bit, at the University of Chicago, a very famous economist there came up with this idea of “public choice theory,” which I've always thought is kind of very strangely named. I don't quite understand the connection between the name and what it is.

Robinson

Yes, it's kind of misleading.

Kim

But the idea is that government agencies, because they lack competition, become inefficient, kind of lazy, and not terribly good at their jobs; therefore you need the private sector to challenge the government to do a better job. Well, what's happened here is that this public choice theory has been turned on its head, and you have these private companies who are now holding their own monopolies on government services and also getting lazy and inefficient and not doing a terribly good job. So, it's a perversion of what was supposed to happen when the private sector came in. What's happening is exactly what you said: due to the lack of oversight, and perhaps the lack of proper incentives and the lack of competition, there are these industries that have popped up with huge profit margins and not a lot of accountability, that are just kind of happily humming along making their money off low-income Americans and the programs that serve them.

Robinson

We've talked so far in generalities about the trend, but could you give us a more specific example of a company or an industry and how exactly this works?

Kim

The book is organized into chapters that go into pretty much every service that can be provided to low-income Americans, whether it's housing, nutrition, or private prisons. Pretty much every aspect of the lives of low-income Americans is infiltrated in some way by some industry that is profiting from their status as a poor person and from some government program that is touching their lives. So, just one example that I'll give is a tax credit for working poor Americans called the earned income tax credit (EITC). It is actually one of the largest federal anti-poverty programs available, second only to SNAP—food stamps. Food stamps provide more than $100 billion a year. The EITC was about $57 billion in 2022. The tax credit is fiendishly complex and difficult to claim, and so, what's happened is this entire industry of paid tax preparers, both large chains like Liberty Tax or Jackson Hewitt that target lower income taxpayers who receive the EITC, or just the fly-by-night people that pop up every spring and offer to do your taxes, have become brokers of this benefit because it is pretty difficult for a person to be able to claim the credit without fear of committing an error. Also, you need to have access to electronic filing, and the law is such that you cannot get the refund for some period of time. So, these tax preparers offer an instant refund, which is basically like a payday loan. This entire industry has popped up to basically take a tax off the tax refund by acting as intermediaries for this benefit and charging predatory fees for the products that will advance the refund to you at tax time. If you have a second, I can give you one example of a used car dealership in Arkansas that I called that offered to do my taxes and sell me a used car on the same day. So basically, the idea there is that they would grab the entirety of my refund, $300 for the taxes, and then I had my selection of used cars to choose from.

There are a lot of partnering industries that will do that with the view of taking advantage of this $57 billion every tax time. So, within housing subsidies—the Housing Choice Voucher Program—there are landlords that specialize in providing housing for Section 8 housing voucher tenants. There are Medicaid dentists who specialize in providing dental care to poor children who qualify for Medicaid. This is an interesting industry because it has been taken over by chains primarily owned by private equity at this point. What we've learned is that if you want to provide dental care to poor children on Medicaid, you do so as a volume business. For one of the places that I visited that's detailed in the book, they basically set up this kind of factory inside a dental office with six to seven chairs arranged like spokes on a wheel with children kind of cycling through. Medicaid doesn't pay enough for mainstream dentists to really take very many Medicaid patients, and there are other reasons why many dentists don't want Medicaid patients, I guess. But what's happened is that because of the shortage of dentists willing to treat Medicaid patients, you've created a niche industry for the Medicaid dentist who's willing to go in there, and many of them have been prosecuted for putting root canals into toddlers and multiple unnecessary fillings into baby teeth, that kind of thing. The school lunch program: that's another place where "big food" has come in and taken advantage of the federal money going to free lunch for poor people. That includes even like Domino's Pizza and Pizza Hut, which even has its own special formula for pizza dough that uses 51% whole wheat flour that complies with federal lunch standards. They call it the A+ Pizza Program.

Everywhere there is a government program, there is a company that's waiting to take advantage of that. Probably the biggest one, though, is within the administration of welfare programs. An example of a company like that is Maximus. It is a publicly traded company, and earned $4.9 billion in revenue last year, a billion of that was gross profit, and they run the welfare system. So, in the state of Texas, the welfare agency is Maximus because the entire thing was outsourced decades ago to private companies.

Robinson

One of the arguments that is made in favor of the free enterprise system is that, yes, corporations will ruthlessly and somewhat sociopathically pursue profit at the expense of all other values. However, they will be disciplined by the consumer because the consumer has the freedom to choose, as Milton Friedman's book is famously named. If you don't like what the corporation is doing, you can go elsewhere, and that will keep the corporation honest. Dishonest corporations will simply go out of business because no one will want to deal with them. But you point out that in the industries that you're describing, this mechanism for disciplining corporations doesn't really exist because poor people don't have the power that the consumer is expected to have that will tame the corporation.

Kim

That's right. In this instance, for the "consumer"—the low-income American—the companies have taken over the role of government. So there is no choice there. If the person wants to interact with the government to get access to the benefits to which they are entitled, they have to interface with the company that the government has outsourced these services to. Say that you're receiving welfare—Temporary Assistance to Needy Families it's called now—there are work requirements to receive your benefits. You don't have a choice. I guess you could not take welfare, but if you want to receive the benefit, you must comply with that work requirement. Who is going to help you comply? Another set of contractors that the state has hired to keep track of your hours and help you find a job if you so need one. So, there's really no choice on the part of the beneficiary. Now, the other customer in this, technically, is the government, but again, there's not a lot of choice for governments either because there aren't 50 companies that are providing the kind of sophisticated level of services that Maximus provides in running an entire welfare agency. There's really only a handful of companies that compete and kind of swap contracts every few years around the country. So, there's no choice or competition on any side of this particular set of transactions.

Robinson

Now I'm sure if I had one of the spokespeople of these companies on, and I put to them the arguments that you have made, they would say to me, we do well financially by doing—

Kim

They would say that they're providing a valuable service, which is true.

Robinson

We provide school lunches, we administer welfare benefits, we run prisons. We do only socially valuable things, or we provide job training. So, where does the evidence come in that they are not giving governments and people what they're paying for, that this is actually really seriously failing across a series of domains?

Kim

I will use job training as an example. And in particular, I'll use Job Corps, which is one of the oldest job training programs. It dates back to the War on Poverty. It was created by Sargent Shriver back in 1964, who had this idea of creating a training program for young adults, and he set up a series of job course centers around the country, mostly in rural areas, for, primarily at that time, young men to go and learn a skill and get a job. It was privatized from the start, as a contractor for companies like Xerox. And although these really large companies held the contracts initially, today they're held by a handful of Job Corps contractors who have hung on to these Job Corps contracts for literally decades at this point, outlasting administration after administration. The government has issued, through the Inspector General's office or through the Government Accountability Office, multiple audits about how this program actually does not work to put low income young adults into jobs. There was one particularly damning report back in 2018 by the Department of Labor's Inspector General that found that some of the students who are coming into Job Corps were going back to exactly the same jobs they had held before they entered the program. So, by any measure, that's not a success, but Job Corps considered it a success. These kinds of programs just kind of hang on and on. These are multimillion dollar contracts that we're talking about to run these centers, and the program remains popular. So, that's a piece of evidence there. I think what I cited earlier about Maximus having a 20% gross profit margin—$4.9 billion in revenues, and a billion of that being gross profit—tells you probably there are some efficiencies to be had that the government isn't reaping there. That's circumstantial evidence of a failure, but could we be getting these services for less money? Then, if you look at the endless list of prosecutions, investigations, and audits involving Medicaid practitioners, to some extent Maximus, paid tax preparers, and dialysis providers who make most of their money from Medicare and Medicaid because kidney failure patients tend to be disproportionately low income, as well as minority—if you look at all the black marks that all of these industries have collected from prosecutions and various government agencies, it begins to look like a cascading series of failures across many industries and companies that add up to a quality of life that's actually severely diminished for the low-income people who are supposed to benefit from these programs. It’s a terrific waste of taxpayer dollars. And there is this bigger question that's been animating our conversation: where would the poverty rate be if we really had taken a hard look at who's delivering these services and how effectively?

Robinson

One point that you make is that, in many ways, these industries have an incentive not to solve the problem that they are being assigned to deal with because the money would dry up. We can ask things like, why should there even need to be a paid tax preparer? If we had a well-designed program, you would just get people the money without having them having to dance through a series of hoops and go through and cut through a ton of red tape.

Kim

Yes, that makes perfect sense to me. But you're right, if the need for tax preparation went away, so would the industry. The industry has spent millions of dollars blocking congressional efforts to get free tax preparation available for low-income taxpayers. They finally kind of lost on this issue with the Inflation Reduction Act, and there is a pilot that the IRS rolled out this year didn't reach that many taxpayers, so that's a defeat, and it's going to be an extremely long time before this becomes available to everyone. But meanwhile, over the last 20 years thereabouts, the tax preparation industry has been fighting tooth and nail, with millions of lobbying dollars spent, to make sure that proposals to simplify the tax code or offer free filing die on the vine. I'll go back to Job Corps as an example—those contractors have their own trade association. They've created a little caucus inside of Congress to support Job Corps. Because Job Corps centers are in rural areas, they do support jobs, so they managed to get Congresspeople on board if they have a job center in their district. It's always fascinated me because these companies are using federal dollars, potentially, to lobby the federal government to keep their business going. I've always wondered how that's okay, but it's happening, and they do wield their political power to keep their industries going. Bail bondsmen oppose bail reform and oppose criminal justice reform. Private prisons have lobbied for three strikes laws and other harsh sentencing laws to ensure that they get plenty of customers coming to their prisons. They're not afraid to use political power, and they wield it pretty effectively.

Robinson

Well, I feel like your book offers a caution to progressives. We might think of it as a victory when we see a $100 million for a job training program, or the headlines about X amount of money. Usually, the way things are reported on, in terms of the amount of money that the government has assigned to deal with problem X, is that's a victory. A member of Congress will say, I just voted for a billion dollars to address X problem. But you point out that unless we trace the money, it's not that it will be meaningless, but that a lot of that money could be squandered or could end up in the pockets of people we are not trying to help.

Kim

That's exactly right. You would be throwing good money after bad in some instances. And don't get me wrong, I think we do need to invest more resources into the programs that do work, but we could be accomplishing a lot more if we were more effectively using the money that we are already spending. That’s not to say that there isn't more investment that is justified in this instance. I'll just go back to Job Corps again because it's a handy example here, and it's also illustrative of kind of the politics around poverty at this moment. There are actually quite a few people who understand that the Job Corps program is not terribly effective. However, for the money that is going to Job Corps, progressives say that, if you get rid of the program, that's $1.7 billion a year that's not going to help poor young adults, and the program is helping some people. And so, the fear is that if the program goes away, then that funding that was going to help young adults would just vanish. And that, I think, is a legitimate fear, and it does lock in the funding that's both going to the program, but it also kind of pushes those who want more funding to say, we need to plus up these programs because this is what currently exists, and it's helping some people, even if it's not helping as many people as it could, and that, I think, is a dynamic we are locked in as a result of where we are now with the politics of poverty.

Robinson

In your conclusion, with the takeaways that you have for policymakers and from all the evidence that you lay out, your number one takeaway is a statement that seems, I think, a little counterintuitive at first: a government doesn't deliver anti-poverty programs. Government can pass and fund anti-poverty programs, but in the real post-privatization world, we have to look at the institutions that are actually tasked with delivering the things that we're funding.

Kim

Yes, we've given away so much of our governmental capacity and governmental authority at this point, and it's always going to be popular with politicians to bash big government. It's very difficult to change that dynamic over 40 years. But the consequence of this hollowing out of the infrastructure and authority of government is that the government is actually not in charge anymore. Now it's these private companies that have taken on the functions of government that are delivering vital services and making really important decisions that affect the lives of very vulnerable Americans, and we're not paying attention to that. We're not terribly aware of what's going on, and we're not considering the larger term implications of this advocation of governmental authority and funding to the private sector on an issue that is of paramount importance to the economy and to the lives of poor Americans.

Robinson

To conclude here, there's a lot that's discouraging when you see all the ways in which the poorest and most vulnerable people are exploited and things that should benefit them are instead hurting them. But one of the positive things is that what you lay out means that poverty may be more solvable than it looks if we have the sort of talking point that we throw $900 billion at this problem and don't solve it. You come along here and say, there's a reason for that. We can address that reason, and it means that we could do a much better job addressing and lifting people out of poverty.

Kim

I think that's absolutely right. I really want to emphasize the point that government programs are effective in reducing poverty. When you look back to 1959 before Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid, the senior poverty rate was 35%, and the poverty rate among children was 27%. These programs have succeeded in virtually eradicating senior poverty. Senior poverty is half the overall poverty rate thanks to the safety net programs that we've created. So, government is effective, can be effective, and it is really a question of what is the most effective a government can be. It is not meeting that bar right now.

Robinson

Finally, could you just tell us, in the life of a poor person in the United States, as compared with perhaps in other countries, what are some of the key points in day-to-day life in which they are losing opportunities and losing money that is ending up in somebody else's pocket, that we could fix? You have to pay the tax preparer, you have to pay their fees; there are fees here, there's a little fee there, and it all adds up. In the life of a person, where are they losing out and how it could be different if we structured this differently?

Kim

In the introduction to the book, I talk about a community right outside Washington DC that exemplifies perfectly what you're talking about here, and in this neighborhood, we're not talking about the Starbucks and the Target, it's more the Discount Furniture Store. But beyond that, there are a lot of tax preparers, so if you want access to the tax refunds that you do every year, you'll probably have to go there to get them. There is a housing complex nearby that primarily rents out Section 8 apartments, and they're not the best apartments because that is a problem that is endemic to the Section 8 housing industry. So, you'll be living in substandard housing, possibly. In this community, there are also several dialysis centers because kidney disease and kidney failure are endemic to lower income and disproportionately minority communities. So, you might be spending some time there. If you are on dialysis, you are not likely to work. You're not likely to have much of a quality of life at all. Next to the dialysis center in the shopping center, you might find the dentist that primarily specializes in Medicaid patients. Will you get the best quality care there? Possibly, possibly not. Your children might go to the neighborhood school where there's a free lunch program. The free lunch program could be that Pizza Hut pizza that I was talking about earlier, versus something that might be more helpful and nutritious and that will affect their quality of life down the road. And unfortunately, in lower income communities as well, there is a disproportionate contact with the justice system, so you'll see a lot of bail bondsmen. And I think what many people don't realize is that even if you're acquitted, even if you're never charged, but you're in jail and can't afford to get yourself out, you're still going to owe the bail bondsman the premium for having gotten you out. And so, there are many people who are innocent who still owe a bail bondsman for a crime that they never committed, or for a crime for which they were acquitted. That is the substantial drain on the financial security of poor Americans: to deal with poor health, a justice system that's unfair, substandard housing, inadequate dental care, inadequate medical care, and then companies that want to grab your tax dollars wherever they can.

Transcript edited by Patrick Farnsworth.