In the creepy Netflix series You, which I’m slightly embarrassed to say I’ve watched one season of, manager and book nerd Joe Goldberg presides over a sprawling New York City bookstore, the kind that any book lover would be excited to come upon and linger in for hours. Besides books, it’s filled with plush chairs and reading nooks and lamps that emit soft light. A charming doorbell jingles when customers enter. Joe’s something of a romantic, and right away he falls for Guinevere Beck, an insecure graduate student who comes into the store and asks his help finding a book. Cringey flirting ensues—followed by obsession, stalking, and serial murder. Meanwhile, the store, Mooney’s—the exterior of which was filmed outside an actual bookstore on the Upper East Side, Logos Bookstore—seems to be doing just fine financially. Little do customers know, Joe has in the store’s basement a climate-controlled rare book storage and repair room-turned-dungeon where he tortures and murders his kidnapped victims in between friendly cash register interactions aboveground.

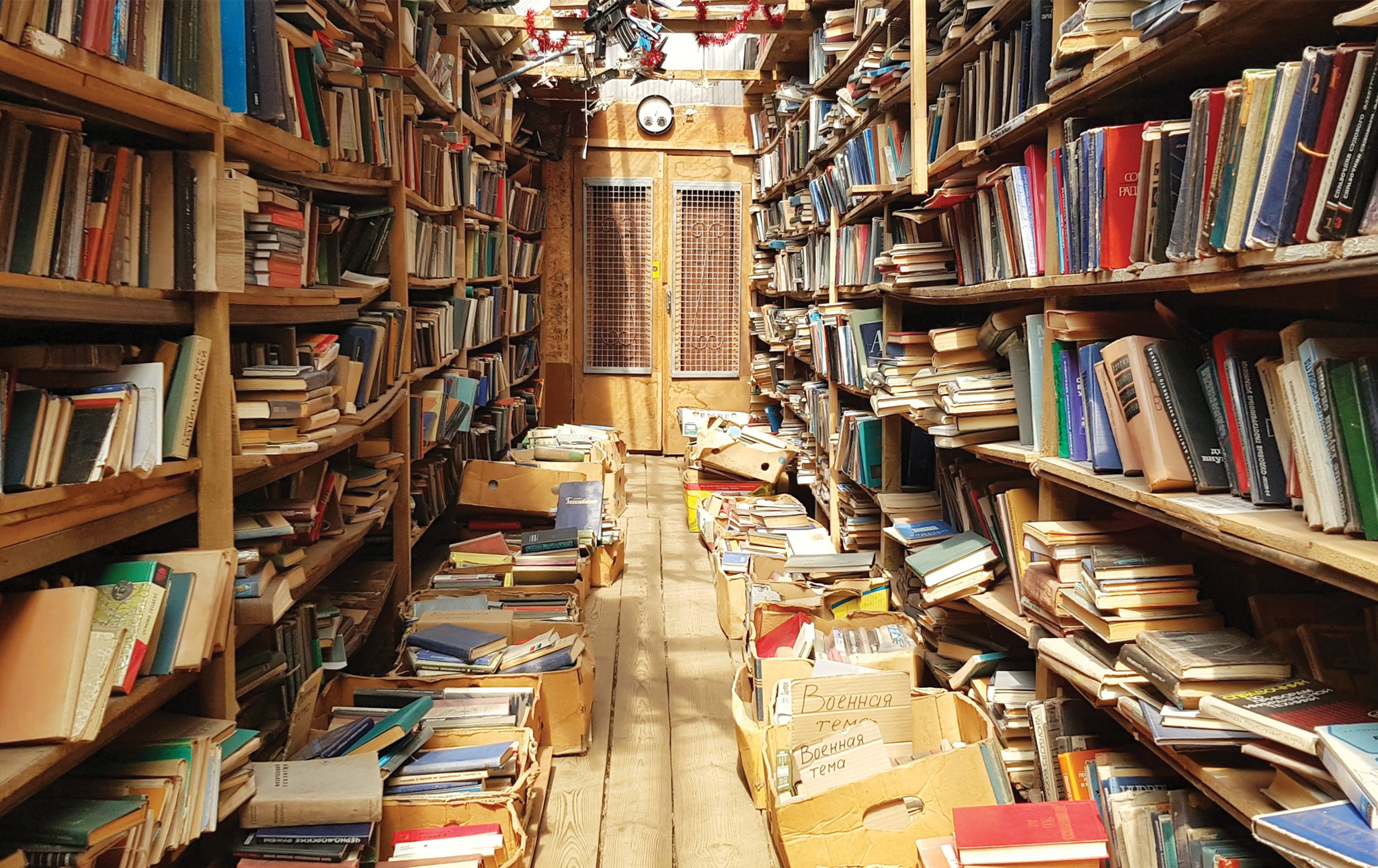

Murders aside, I find myself wishing I could visit a bookstore like Mooney’s. (Better yet, to walk—not drive—to one.) Bookstores, whether hosting author talks, book release events, or other gatherings, provide important social functions to their communities. Sociologist Ray Oldenburg in 1989 coined a term for places like bookstores, cafés, coffee shops, and hair salons, among others: “third places,” sites where people spend time while not at work or at home. As historian Evan Friss notes in his 2024 book The Bookshop: A History of the American Bookstore, third places “function as critical sites for intellectual, social, political, and cultural exchange. They nurture existing communities and foster new ones.” Because they “cost nothing to enter,” “they are de facto public spaces, gathering spots.”

Sometimes bookstores are overtly political. In the United States, bookstores owned by women, African Americans, and LGBTQ people, for example, have played an important role in educating and organizing community members around the empowerment of marginalized groups. Feminist bookstores sprang up in the 1970s. Black-owned bookstores were targeted by the FBI as part of its larger operation to suppress Black Power and Black nationalism in the late ’60s. The ’80s and ’90s saw the rise of queer bookstores in parallel with the HIV and AIDS crises. Black-owned bookstores saw a surge in demand for books about antiracism after the murder of George Floyd in 2020, which led to what was possibly the largest protest movement in U.S. history.

Bookstores are going to continue to play important roles in social justice work in the coming years. We’re facing right-wing attacks on everything from LGBTQ rights to immigrants’ rights to women’s reproductive rights to the teaching of African American history. And book bans, which tend to target books about racism, gender, sexuality, and history, are going to continue to be a problem. As Stephen King put it, kids should “haul [their] ass to the nearest bookstore” and find the books that adults don’t want them to read. But they can’t do that if there’s no bookstore.

Bookstores, defined by the Census Bureau as primarily engaging in the sale of new books, are, Friss notes, an “endangered species.” According to Census Bureau data, the number of bookstores has roughly halved from 1998 to 2019, going from 12,151 to 6,045. In 2021, that number had gone down to 5,591. The chain Borders, for instance, went bankrupt in 2011, closing at least 400 stores that year. During the early years of the pandemic, bookstores, like other physical businesses, were impacted by public health shutdowns. Used bookstores, too. Half Price Books, a Dallas-based used bookstore chain that started in 1972, closed all 126 of its stores temporarily in the spring of 2020. Even though the chain survived, they laid off or furloughed over three-fourths of their workforce in April 2020. Other stores closed for good in part because they weren’t able to transition their business model to accommodate the pandemic demand for online or curbside sales. But then the New York Times reported in 2022 that over 300 independent bookstores had opened, including a number of minority-owned stores, an encouraging sign after the “slump” of the early pandemic years and something of an “indie bookstore renaissance,” as poet and bookstore co-owner Danny Caine put it in his 2023 booklet 50 Ways to Protect Bookstores (a real gem that I highly recommend).

The bookselling industry, like the publishing industry, is “traditionally overwhelmingly white,” so the opening of minority-owned bookstores has been an especially important development in recent years. Caine notes that 96 bookstores have been opened by people of color since 2020, according to the American Booksellers Association. While not all minority-owned bookstores will necessarily be overtly politically oriented, such stores often feature books written by and about racial and ethnic minorities, which can serve as an immediate antidote to public school education systems whose textbooks have historically taught white supremacy and whose curricula often feature books written by mostly white authors and that include mostly white characters. (I attended majority-minority public schools and recall the curriculum being Eurocentric.)

Nowadays, most books aren’t purchased in the kind of bookstore shown in You. They’re more likely to be purchased from Amazon.com, the largest bookseller, or in physical stores like Costco or Target, the two largest sellers of books among physical retail stores (although Costco has plans to make bookselling seasonal, as opposed to year-round, at many of its stores). Caine points out that bookselling is hard work for stores that deal primarily in books, and this makes conditions ripe for labor exploitation. As bookseller Michael White explained in “A Brief History of Organizing at Half Price Books” in the December 2023 issue of The North Meridian Review:

While Booksellers at various other bookstore companies have an organizing precedence going back to Powell’s Books in the late 1990s, recent union organizing among Booksellers has been growing at a higher frequency and with a higher degree of militancy due to deteriorating living conditions, lack of living wages, lack of preventative health care, and a general degeneration of the career into another bad retail job.

In December of last year, 110 unionized workers went on a four-day strike, which resulted in a 37 percent pay raise, at New York City’s famed Strand Books, which had laid off most of its staff during the 2020 lockdown. (Strand’s owner, Nancy Bass Wyden, is the spouse of Oregon Senator Ron Wyden.) In his piece about Half Price Books, White explains the factors that led to unionization at nine stores in the Midwest after the initial 2020 lockdown. The previously “worker-friendly” Half Price Books had, over the years, reneged on the “initial ideals” espoused by its founders. Initially, workers had good pay, a healthcare plan entirely paid for by the company, childcare benefits, and paid hour-long lunch breaks, among other perks: “a system of profit sharing, quarterly bonuses, a holiday bonus, and contributions to 401k accounts. Booksellers had the opportunity to move up in the company, which used to have a strict policy of only hiring from within.” But in the early aughts, things started to go south, as the position of bookseller became “deskilled and computerized,” healthcare benefits were chopped into costly tiered plans, and lunch breaks became unpaid. When staff started to unionize, the company turned to union busting, enacting “captive audience” meetings and bringing in people higher up in the company to micromanage booksellers and “make people fearful and quiet.” Despite this, White remains defiant. “[M]ore stores will follow,” he writes.

Supporting bookstore worker unionization is one of Caine’s suggested “50 Ways to Protect Bookstores.” Caine’s booklet breaks down into three categories: “individual habits and choices,” “how policymakers and those in power can help,” and “active community membership.” Another way to think of it is: protect sellers, protect workers, and protect communities/books. Basically, it boils down to patronizing the stores you would like to see stick around; supporting antitrust enforcement (think: lessening the power of Amazon); supporting pro-worker legislation (universal healthcare, unionization); and supporting your community’s public amenities (libraries, public transit) and local news services. Caine’s tips are good advice in general to help foster a more literate and connected local community. The one thing I would add upstream of bookstores is to support local public schools and their libraries as well as adult education efforts when possible. Our country has a major literacy problem among both children and adults, and in this regard we need to provide a high-quality public education for all children as well as continuing education for their parents. These efforts are necessary if we wish to cultivate a citizenry that is literate and that enjoys reading for its own sake and enough to patronize bookstores and libraries.

The closure of bookstores has been frustrating me most of my life. I grew up in a family of readers, and we loved our book places—whether public libraries, where we made off with epic hauls of books packed into crates, or bookstores. We didn’t buy too many full-price books when I was growing up because they weren’t affordable. But as my older sister and I aged out of libraries—I’m not sure why this happened, maybe libraries weren’t “cool” anymore or we’d just been conditioned to be consumers who purchased things instead of borrowing them1—we spent more time in bookstores. The first bookstores to disappear were the B. Dalton at the local shopping mall and the local Bookstop, where you could get a “member’s discount.” In my elementary school years, we spent many a Friday evening in that Bookstop store, savoring hours browsing at our leisure. Then we lost our neighborhood strip mall Half Price Books, which was very disappointing. My sister and I had spent our teenage years browsing and buying from that store—it’s where I acquired a bunch of old copies of Ray Bradbury’s books like Dandelion Wine and The Golden Apples of the Sun, whose strange covers led me to even stranger stories.

"The Golden Apples of the Sun" book cover

"The Golden Apples of the Sun" book cover

Not too long after that, we got our first Barnes & Noble, which plopped itself down across the highway from my high school in the years before I graduated in 2000. Barnes and Who? The book prices struck us as shockingly expensive. And no discount?! (They now have a “membership and rewards” program.) The store was brightly lit and tidy and huge. But we have always longed for the more serendipitous experience of our neighborhood Half Price Books.

When I found out in 2020 that one of my more recent favorite used bookstores was closing for good, I was truly saddened. When I found out the reason why—the rent was too damn high—I was angered. I never got to see the final days of the store—the Half Price Books in Houston’s Rice Village, which had been around for 38 years—because its last day of business was March 8, which happened to be Super Tuesday, which found me at the local Bernie Sanders campaign office instead. I was calling people to remind them to get to the polls. I had been canvassing for the campaign since December and hadn’t even found out about the bookstore’s sad fate until it was too late to say goodbye. Even now, looking at a photo of the store’s last day, the shelves nearly emptied out, I get misty-eyed. I’d spent so many hours in that store! Mostly alone, but also, in the aughts, with my boyfriend at the time, whose impact on my political consciousness I still look back on with nostalgia some twenty years later. I was always finding gems at the bookstore to squeeze onto my cluttered bookshelves. They were the cheap kind from office supply stores that bowed in the middle under the strain of too many books. I can still remember the layout of the store. In the center near the cash registers close to the entrance, the CDs and records. To the right of the entrance, the journals and art books. Some rows behind that, political science and history. Off to the left, down a hallway with uneven flooring, a room that was home to psychology and sociology. Up the winding staircase to the second floor, fiction, endless medical textbooks, and study guides—physiology, anatomy, biochemistry, and so on—along with nonfiction by medical doctors and science writers. (The bookstore was down the street from the Texas Medical Center, a large complex of hospitals and other institutions, and the college of medicine we attended, hence the abundance of medical books.)

The years I spent going to Half Price Books were some of the best and worst of my life up to that point. Medical education was a kind of straightjacket, a prim induction into a conservative profession that was honorable (or at least had the potential to be) and storied but marred by the gross injustice of the American for-profit healthcare system, one that leaves people ruined from medical debt or sick because they can’t afford care. I wasn’t even sure I really wanted to be there, but after I’d left a graduate writing program that I’d felt was a poor fit the year prior (just a few weeks after matriculating, embarrassingly), I’d decided to take this supposedly more practical route with my life. M, as I’ll call him, was wonderfully different from our competitive and gossipy classmates. While everyone was focused on acing tests but acting like they were self-conscious about their abilities, M was off reading Naomi Klein’s No Logo and anything by Noam Chomsky, listening to the speeches of Malcolm X, and watching The Battle of Algiers (while still acing all the tests). He was asking questions no one else was asking. Like, why are medical professionals helping to torture and interrogate detainees at Guantánamo Bay? Wasn’t that a violation of medical ethics? He asked, “Why?” more than anybody I’d ever met. As readers, we spent a lot of time in the Rice Village store as well as another one not too far away in an area called Montrose. (Sadly, that store closed the following year, in 2021. I never got to say goodbye to that one, either.) Other stores we frequented included Barnes & Noble (that location closed, too, in 2022) and Bookstop (acquired by Barnes & Noble), which had taken over the historic Depression-era art deco Alabama Theater building and transformed it into a strange-looking bookstore (which has also closed since then and is now a Trader Joe’s). Then there was 1/4 Price Books, which we never felt had a very good selection, and the owner was not friendly (although one Reddit user remembers otherwise, saying he was “incredibly knowledgeable and kind”).

I can still remember the books that I found in those years and the impact they had on me personally and professionally (especially in my decision to work with low-income and minority patients once I finished my medical training). They stayed on my shelves for many years, and it was only because of frequent moves that I eventually had to part with them (although I still have the original Fromm and Farmer books in my possession). The books were:

Even though I wouldn’t discover the work of historian Howard Zinn until some years later, I look back on that time as a perfect example of what Zinn wrote about how people’s political consciousness changes: “[Y]ou read a book, you meet a person, you have a single experience, and your life is changed in some way. No act, therefore, however small, should be dismissed or ignored.” As Friss puts it, “The right book put in the right hands at the right time could change the course of a life or many lives.” I didn’t know it at the time, but I was discovering socialism in those books.

After we got our medical degrees—and long after M and I had split—our classmates all went our separate ways for training programs. While many left town, I stayed. For a long time, any time I’d walk into a bookstore—especially one with an in-store cafe, where you’re hit with the smell of coffee right as you enter—I’d remember my time with M and those years of intellectual discovery, and I’d feel dreadfully sad about what was no more. I held on to that sadness, wore it like a blanket—I think so that I could feel something in those zombified years of training where all I did was go to the hospital and then come home and sleep. Now, when I walk into a bookstore, even one with coffee, I’m mostly okay. Sometimes I feel a twinge of something bittersweet, if anything.

“More so than bars or coffee shops, [bookstores] are also places in which to get lost, and, by way of the books, to escape reality. For every chatty customer, there’s another who prefers to be left alone. To be by oneself among others. To feel a book’s heft. To smell a paperback’s perfume. To savor slowed time.” —"The Bookshop" by Even Friss

Besides finding good books, I especially like the slowing of time that occurs when browsing in a used bookstore. As Jason Guriel puts it in his essay collection On Browsing, slowing down is “the benefit of old-school browsing in the first place.” Browsing in general is similar to cooking or going for a walk without listening to anything on headphones in that you have to slow down and pay attention to the physical world around you. With cooking, you have to notice the transformation of food by sight, sound, and smell (garlic in oil burns quickly, do not leave it unattended; there are degrees of stiffness to achieve when whipping an egg white; is your pot of soup gently simmering or frothily boiling?). With walking, you have to watch out for an uneven sidewalk or an unleashed pet coming your way. Similarly, the act of browsing, Guriel notes, is “calibrated to the natural pace of a body moving through space.” Contrast that with scrolling a screen, where things whirl past you at the pace of a finger swipe.

"The Golden Apples of the Sun" book cover

"The Golden Apples of the Sun" book cover