Hard Times in Professional Wrestling

Professional wrestling embodies the tension between art and commerce, a tension inescapable in a monopolized industry under capitalism.

Professional wrestling is a bricolage built for over a century from whatever could be grabbed from any art form or sport that happened to be passing by. It’s theater, it’s television, it’s combat, it’s carnival. It’s a soap opera, but with backflips off the top rope. Its roots are deeply proletarian—surely the origin of the “wrestling fans are so dumb they don’t realize it’s fake!” libel—and its branches are frenetically transcultural, stretching from the United States to Britain to Mexico to Japan and back again. Wrestlers are actors and acrobats, choreographing and performing an elaborate series of stunts right after delivering a heart-pounding monologue about kicking your ass. “Here we find a grandiloquence which must have been that of ancient theaters…” cultural critic Roland Barthes wrote in 1984. “Even hidden in the most squalid Parisian halls, wrestling partakes of the nature of the great solar spectacles, Greek drama and bullfights: in both, a light without shadow generates an emotion without reserve.”

American professional wrestling has also, after spending most of the 20th century fragmented into regional promotions, become so monopolized by the WWE (World Wrestling Entertainment) that All Elite Wrestling (AEW), founded by billionaire father and son team Shahid and Tony Khan, seems like an underdog with its $2 billion estimated valuation. Last year, WWE settled an antitrust lawsuit after the court rejected their move to dismiss the case, with the judge saying WWE’s arguments were “improperly asserted” since they “contained no facts.” Meanwhile the plaintiff, Major League Wrestling, claimed that WWE had captured 92 percent of the revenue from the media market for professional wrestling. WWE uses its monopoly power to crush and exploit labor, categorizing its wrestlers as independent contractors while forbidding them from working for third parties and pressuring them to perform before injuries have fully healed. While the top stars are well compensated, WWE typically has dozens of wrestlers under contract who are paid far less. Even for the top stars, as is the case with so many professional athletes, the physical ramifications of their work can be severe, even if their career isn’t cut short by an injury. “Wrestling… has a tremendous entrance plan. You come in, it’s ‘boy, here you are,’ you’re rock and roll and everything is wonderful,” Rowdy Roddy Piper once said. “It’s got no exit plan… What would you have me do at forty-nine? When my pension plan, I can’t take out 'til I’m sixty-five? I’m not gonna make sixty-five. Let’s just face facts, guys.” Piper died at 61.

Wrestlers, a docuseries directed by Greg Whiteley and released last year on Netflix, follows the fortunes of Ohio Valley Wrestling, an independent wrestling promotion in Kentucky. OVW is small, a speck of dust compared to WWE or AEW. Yet in its documentation of this speck of dust, Wrestlers lives up to its title’s implied claim of encompassing professional wrestling as a whole. We witness all that is beautiful and horrible about wrestling in this microcosmos. That tension is never resolved, not permanently: now spikey and now smooth, perhaps, now intensified and now dissipated. It forms a part of the larger tension, inescapable in a monopolized industry under capitalism, between art and commerce.

OVW is the only indie wrestling company in the United States to air a weekly TV show, just like the big boys—albeit theirs is broadcast on a local Christian network that just wants to fill out its schedule. OVW once acted as the developmental pipeline for WWE stars, including people like John Cena, Randy Orton, and Batista (now better-known in Hollywood as Dave Bautista), but WWE ended that relationship in 2008, moving development in-house. A decade and change later, when Wrestlers begins, OVW has just come within a hair’s breadth of bankruptcy before being saved by a pair of outside investors.

The creative force behind OVW is Al Snow, who wrestled in WWE and Extreme Championship Wrestling (ECW, ultimately bought by WWE) in the 1990s and 2000s. With his tree-trunk arms and saggy belly, he is practically the archetype of a retired wrestler. His main gimmick as a wrestler involved carrying around a mannequin head that he spoke to and even wrestled as a tag team with: Al insisted that Head was crazy, not him. Al was never a headliner, but he was closer to the top than anyone at OVW could imagine. In the series, we see The Rock pretending to not know who he is in an old promo, and it makes his position clear: within touching distance of the marquee names, but unmistakably apart from them. Today, he is minority owner at OVW after the recent bailout but retains creative control, from deciding on storylines to feeding the TV commentator lines in his earpiece. He has highly specific ideas about how wrestling should be, and he pursues them doggedly, regardless of whether the result is “good,” so to speak. The televised matches might look like crap, but TV is part of what wrestling is, damn it, even if it’s grainy and the sound is bad. Al evokes, for me, Ben Gazzara’s character, Cosmo, in the John Cassavetes film The Killing of a Chinese Bookie. Cosmo is a strip club owner so deeply invested in his mediocre burlesque show that he takes time out from carrying out a hit for a mob boss to call the club and check how the “Paris number” went. (The employee isn’t sure what the “Paris number” is.)

Al is a tragic figure, devoted to his art—which no one respects or cares about—in a totalizing way. For him, all else is just distraction. His ambition outstrips his ability for the practical realities in which he finds himself. But he’s also a triumphant figure, who in his devotion to his art—to making art for art’s sake, making it the best he can regardless of what he gets in return—achieves something transcendent. What ceases to matter is whether the art is "good" or not. Al's ambition, like his art, is something better, purer, than that.

This puts him in conflict with Matt Jones, one of the new investors, who would like OVW to stop lighting piles of his money on fire, thank you. It would be easy to paint Matt as the villain of the series: in the war between art and money, Al is the art and he’s the money. Matt has a ton of bad ideas, a sightline that goes no further than the borders of Kentucky, and an insistence that he can see the future while Al’s stuck in the past (even as Matt hosts a radio show). He gets the OVW wrestlers to tour the state, at county fairs mostly. Not only does this leave them tired, overworked, and underpaid, but it relies on what Al calls “cheap heat”: getting cheers for the hometown team and boos for their rival, instead of through character and story. It runs counter to the very core of wrestling, which is capable of telling stories in immediate, intelligible ways: “The physique of the wrestlers therefore constitutes a basic sign, which like a seed contains the whole fight,” Barthes writes. “But this seed proliferates, for it is at every turn during the fight, in each new situation, that the body of the wrestler casts to the public the magical entertainment of a temperament which finds its natural expression in a gesture.”

But at least in the context of this failing, flailing indie wrestling company, Wrestlers gives due weight to both sides of the argument. Matt wants OVW to make money—or at least stop losing money—and he needs to figure out a way to do that when nobody else cares. Matt isn’t Shahid and Tony Khan; he can’t keep burning money until things turn around. The TV show loses money every week, and they can’t keep going the way they were, especially when “the way they were going” brought the company so close to financial collapse. Matt is under a tremendous amount of stress, which no doubt contributes to his inability to manage his epilepsy. He has a seizure on-screen, and it was the first time I ever felt like I was seeing my experience of epilepsy from the outside—the way he comes out of it especially, talking nonsense while insisting he’s fine. The worst part about having a seizure, he says afterward, is how scared other people look.

While Al and Matt battle about the state of the company, a whole roster of wrestlers work at OVW while hoping for something more. A melting pot of has-beens and never-weres, of people on the way up and people who remain convinced that they’re on the way up despite abundant evidence to the contrary. People who surely deserve to be signed to WWE or AEW, and maybe they will, maybe they won’t, but they’ll put their body on the line and their lives on hold in the meantime. Dislocate a shoulder, blow out a knee, scramble from one paycheck to the next.

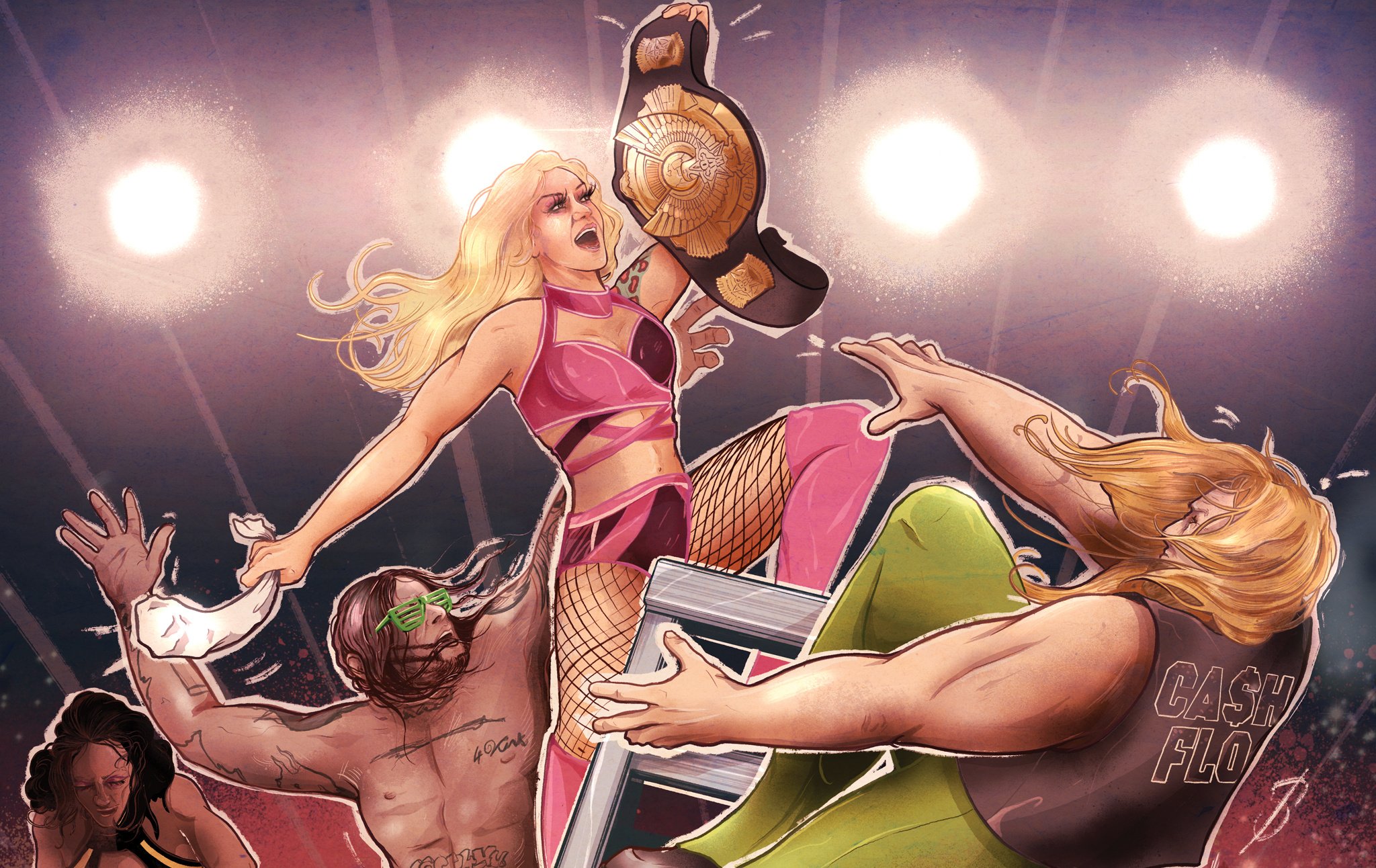

The most compelling of these is Hollyhood Haley J, who pops like a live grenade. When one of her matches finishes early, she has to vamp for ten minutes, filling the time before the next match, and it’s still some of the best wrestling I’ve ever seen. Haley is preternaturally talented, a born star, but deeply troubled in a way that both explains why she wrestles and threatens to spoil her career before it truly begins. Her mother—The Amazing Maria, also a wrestler—was incarcerated for drug dealing convictions for much of Haley’s childhood, and since she had no relationship with her father, she was cared for by relatives and left feeling like a burden. She was raped at the age of 15 and ran away from home at 16. After she and her infant son were held at gunpoint and robbed, she ended up turning to wrestling, which allows her to both escape from her traumas and work through them in her art. She and her mother have reconnected, but their relationship isn’t exactly repaired. The lingering resentment and trauma there is mediated through—what else?—wrestling. They have a hardcore match—Maria’s specialty, in which there are no disqualifications and so weapons can be used—and you can sense the depth of feeling behind every trash can lid and thumbtack. (The work they do together at the syndicated Women of Wrestling (WOW) is way less compelling, but they get paid a lot more than they do at OVW.)

Illustration by John Biggs

Illustration by John Biggs

Haley’s older boyfriend, meanwhile, is clearly jealous of her talent and her budding success, which he expresses by claiming that women’s wrestling is inherently bad and only being promoted because of the woke agenda. He’s a loser and a misogynist with some of the worst tattoos I’ve ever seen, but there’s a tragic air to him, too. It’s easier for him to invent this narrative than concede that his time has come and gone without him “making it,” and Haley still might.

They all dream of making it. Haley is sure she’ll work in WWE or AEW someday soon. Meanwhile, another wrestler, Shera, was briefly signed to WWE in 2018: when he was let go, he contemplated suicide before deciding to commit to following his dream, fantasizing about WWE one day coming back to him, begging. “I’m only going back to India,” he says, “when I make a huge name on my own.”

But making it is a trap. It fetishizes success in industries where exploitation is baked in—and not just wrestling, but all entertainment industries, where high salaries in the short term are sweeteners in a Faustian bargain. To “make it” is to see your peers not as comrades or collaborators but as competition for a limited number of slots. It belittles work made outside of the gatekeeping institutions, like WWE, as both art and labor: just the necessary drudge work to prove yourself worthy, itself unworthy of artistic respect or adequate compensation. American college sports earn billions in profits while the athletes that make it happen go unpaid, justified on the elusive promise of maybe, maybe being drafted into the NBA or NFL. Musical artists work as session musicians before they ever get to record under their own name. Emerging writers get paid in “exposure,” which is, it turns out, not legal tender. All are told to “earn their dues,” to “spend money to make money.” Dreams are grist to the mill of billion-dollar conglomerates, ground up for profit.

When Al Snow talks about his regrets, it’s the moments he didn’t push hard enough for his creative vision, when he acquiesced to a joke ending for a match instead of being true to his character and story. Here at OVW, he has artistic freedom. The trouble is, artistic freedom doesn’t pay the bills.