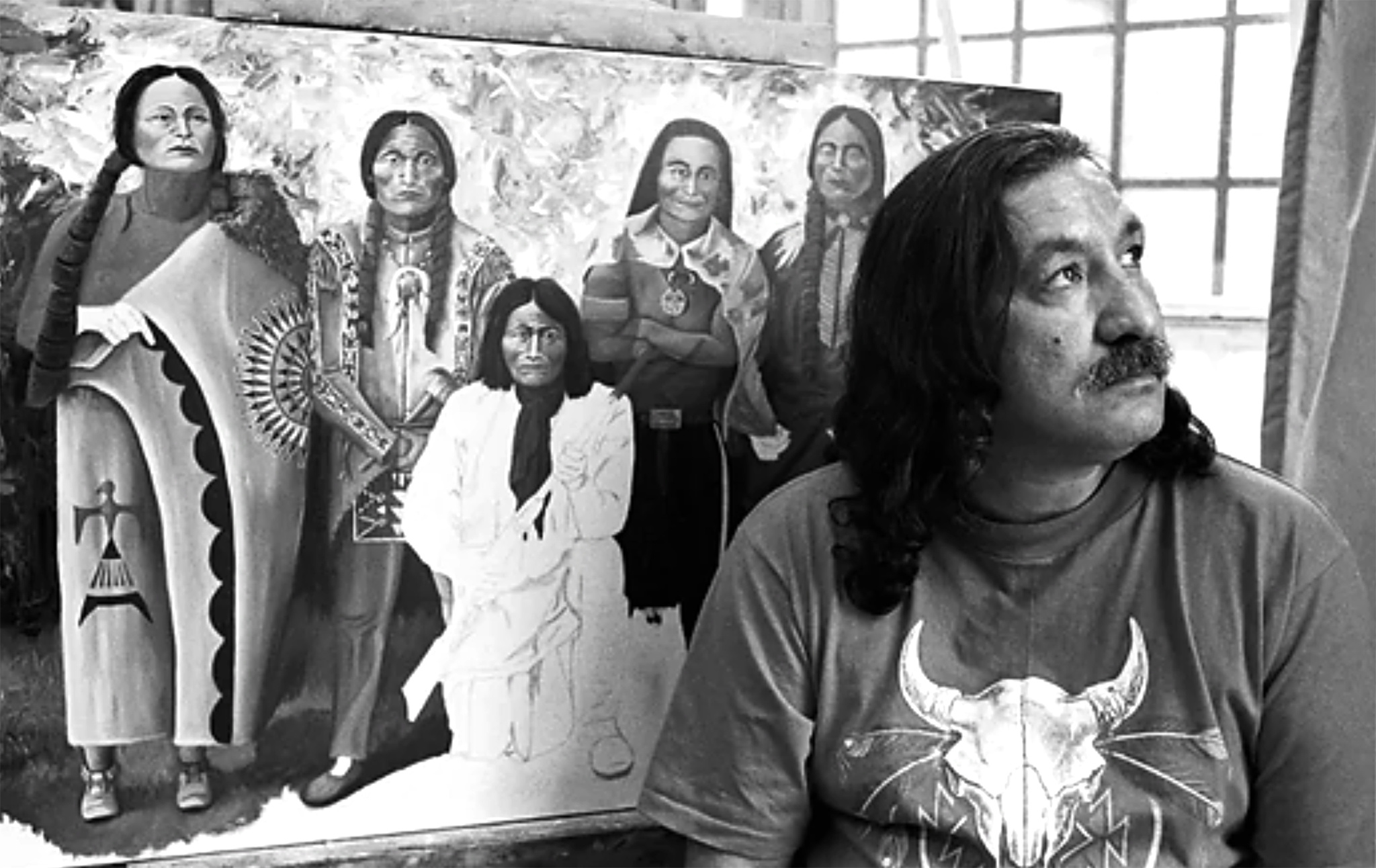

Free Leonard Peltier—Before it's Too Late

The Native American activist’s continued imprisonment is one of America’s worst injustices.

In Florida, Leonard Peltier—one of the longest-held political prisoners in the United States, or anywhere else for that matter—was recently denied parole for the sixth time. Peltier is a member of the Turtle Mountain Chippewa, Dakota, and Lakota Sioux tribes, and a lifelong activist for the rights of Native Americans. In the 1970s he joined the American Indian Movement (AIM) and was arrested for the murder of two FBI agents at the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota. The charges were never adequately proven, and his 1977 trial, which was full of official misconduct and deception, violated the most basic rights of due process. Despite this, Peltier was sentenced to two consecutive life sentences and has served more than 49 years behind bars. He’s now 79 years old, and won’t be eligible for another parole hearing until 2026. Given his poor health, he may not reach that date alive.

This is a terrible injustice, but there is still time to correct it. The U.S. Department of Justice has a policy allowing for “compassionate release” for federal prisoners who meet certain conditions, including medical conditions and advanced age. This year, both indigenous leaders and several U.S. lawmakers have urged that Peltier be granted such a release. President Biden, too, can grant Peltier clemency any time he likes; all it would take is the stroke of a pen. Releasing Peltier wouldn’t give back the decades of freedom the FBI, courts, and prison system have stolen from him. Nothing can do that. But it would be the right thing to do, and if they actually care about justice, Biden and the Justice Department should give the order.

The historical background is important here. Peltier is sometimes described as a militant, and AIM as a militant movement, and to an extent that’s accurate. But it’s important to remember that their militancy only came about as a response to sustained racist abuse, state-sponsored violence, and the forced displacement of Native Americans by the U.S. government. In the first place, the American Indian Movement arose as a response to the abhorrent policy of “Indian termination,” which was practiced by the United States from the 1940s to the 1960s, and it’s in that context that this resistance has to be understood.

Essentially, the government’s policy in these decades was to forcibly assimilate Native Americans into broader U.S. society by removing official recognition of their tribes, literally “terminating” them as legal entities. Millions had already been forced to migrate onto reservations in the previous century, where they were officially considered “wards of the state.” Depending on the tribe and the area, they were often dependent on the U.S. government for things like education, healthcare, employment, and even food (as reservations were frequently placed on the worst land available for agriculture.) Under the guise of granting a fuller citizenship, “termination” stripped the sovereign authority from tribal governments, placed Native Americans under the jurisdiction of U.S. state and federal law (and taxes), and abruptly cut off federal resources and services to the reservations. As journalist Max Nesterak writes for American Public Media:

The goal was to move Native Americans to cities, where they would disappear through assimilation into the white, American mainstream. Then, the government would make tribal land taxable and available for purchase and development. The vision was that eventually there would be no more BIA [Bureau of Indian Affairs], no more tribal governments, no more reservations, and no more Native Americans.

More than 100 tribes—including the Turtle Mountain Chippewa, to which Peltier and his family belong—were ordered “terminated” during this era, and Native Americans lost more than 3 million acres of their land as a result. In his prison memoir, My Life is My Sun Dance, Leonard Peltier recalls what “termination” looked like in practice:

We were given two choices: either relocate or starve. Later, court decisions would declare this compulsory policy totally illegal, which it was, but that was no comfort to us at the time. We pleaded with the government to let us stay on our land and to create some employment on the reservation, as they had promised to do, but all that was in vain[...] Hunger was the only thing we had plenty of; yeah, there was plenty of that to go around, enough for everybody. When frantic mothers took their bloated-bellied children to the clinic, the nurses smiled and told them the children just had “gas.” A little girl who lived right near us on the reservation died of malnutrition. Sounds like “termination” to me.

This reads like an account of colonial atrocities from the 1600s, but it’s not. It happened within living memory, under the administration of modern leaders like Eisenhower and JFK. The U.S. government deliberately starved entire communities and planned the slow eradication of Native American culture and identity. They also forcibly separated tens of thousands of Native American children from their families and shipped them off to abusive boarding schools, where they were forced to speak English and physically punished for any expression of their own culture (something Peltier and his siblings experienced in 1953) or even killed. Scholars refer to this kind of policy as “cultural genocide” or “ethnocide,” and it was the logical successor to the mass slaughter of Native Americans in the previous centuries. Needless to say, it violated all kinds of human rights—but the United States has a habit of ignoring such things, and among the international community, only the socialist countries really complained.

It was injustices like these that caused the formation of AIM in 1968, in Minneapolis. The movement initially focused on getting aid to Native Americans who needed it, raising awareness of the issues they faced, and carrying out peaceful—if dramatic—acts of protest. Starting in 1969, members of AIM joined other Native American protestors to occupy the former prison on the island of Alcatraz for 19 months, citing an 1868 treaty that granted land abandoned by the federal government to Native Americans. Showing a bitter satirical side, they offered to buy the island for “$24 in glass beads and red cloth,” the meager price paid to its original inhabitants, and to set up a “Bureau of Caucasian Affairs” to govern any white people who chose to remain. Unamused, the Nixon administration tried to starve them out by cutting off electricity and fresh water to the island, then sent federal marshals to arrest the 15 occupiers who had refused to leave. The action inspired a similar one the following year, in which a coalition of Native American protestors from various tribes—including a young Leonard Peltier—occupied Fort Lawton in Washington, which had been declared surplus land by the U.S. Army. (They eventually won a concession of 20 acres, which now house the Daybreak Star Indian Cultural Center.)

Peltier officially joined AIM in 1972, and took part in the “Trail of Broken Treaties,” a march on Washington, D.C., that culminated in a six-day occupation of the Bureau of Indian Affairs building—just a few blocks from the White House. In his memoir, he recalls being met with excessive violence from the police and military at each new protest:

Men, women, and even children were beaten—and much worse—when Indians were arrested[...] At Fort Lawton the government confronted us with machine guns and flamethrowers. When we were arrested, the soldiers fondled the women in front of the men, trying to trick us into reacting so they could justify killing us. Those of us singled out as leaders were beaten in our military jail cells in the army stockade. I refused to leave until every one of our group of warriors was allowed to leave. That got me several extra beatings…

To underline the point: it was the U.S. government who first used violence against AIM, not the other way around, and caused them to turn increasingly to armed self-defense as the 1970s wore on.

This was also the era of COINTELPRO, the covert war against American dissidents which saw the FBI assassinate Fred Hampton, the chairman of the Illinois Black Panther Party, in his bed and write an anonymous letter urging Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. to commit suicide. Just as it did with Black liberation movements, the Bureau did everything in its power to destroy AIM. FBI agents spied on the group’s meetings, spread propaganda that accused it of nonexistent connections to communism and the Viet Cong, and even drew up plans for what they called “FBI Paramilitary Operations in Indian Country.” Finally, beginning in 1973, the hostilities turned deadly.

As Lower Brule Sioux historian Nick Estes has written, South Dakota’s Pine Ridge reservation—where the two FBI agents were killed—was divided between two groups in the early 1970s. On one side was a conservative Oglala Sioux leadership—administered by tribal president Richard “Dick” Wilson—that opposed AIM’s protests, especially the occupation of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. On the other side was a more radical faction that supported AIM and felt Wilson was making too many compromises with the U.S. government, essentially becoming a collaborator against his own people’s interests. In 1972, Wilson established a paramilitary police force called the Guardians of the Oglala Nation (aptly nicknamed the GOONs) to crack down on his opponents, and banned members of AIM from the reservation. In response, the dissident faction called on AIM to stage a protest on the reservation itself—which they did, occupying the site of the notorious 1890 Wounded Knee Massacre with around 200 local supporters. There, they demanded the restoration of tribal sovereignty to the Oglala people—which would mean dissolving Wilson’s government, who they condemned as “Bureau of Indian Affairs puppets.” In the 71 days that followed, the FBI, BIA, and U.S. Marshals surrounded Wounded Knee, leading to a standoff. Throughout, the FBI armed and supported the GOONs as they launched periodic attacks on the camp. By this point, many AIM members were armed, and a crossfire broke out between the factions. A U.S. Marshal was shot and wounded by gunfire coming from Wounded Knee (though exactly whose gunfire is unclear) in March 1973. Soon after, the blockade was dramatically ramped up to include fighter jets and armored vehicles, and two Native American activists, Frank Clearwater and Lawrence “Buddy” Lamont, were killed—Lamont by a sniper, Clearwater by a “stray bullet” of uncertain origin. On May 8, AIM surrendered.1

Leonard Peltier wasn’t at Wounded Knee during the 1973 occupation. Instead, he came to the Pine Ridge reservation to deal with its violent aftermath. In the wake of the protest, Wilson and the GOONs began what Estes calls a “vicious crackdown on reservation dissidents,” during which at least 60 people associated with AIM were murdered under suspicious circumstances. This “reign of terror” led two Oglala elders, Cecelia and Harry Jumping Bull, to request protection by AIM’s more militant members in 1975. Peltier was one of the small group who answered their call, camping out on the Jumping Bulls’ ranch to serve as bodyguards. On June 26, 1975, two FBI agents—Jack Coler and Ronald Williams—came to the ranch, purportedly trying to serve an arrest warrant for a Native American man named James Eagle. A firefight broke out between them and the AIM members, during which around 150 nearby FBI and BIA agents (who had never left the area after the Wounded Knee standoff) surrounded the ranch. Soon, Coler and Williams had first been injured, then fatally shot at point-blank range. One AIM member—Joseph Stuntz Killsright, of the Coeur d’Alene tribe—was also killed by an unknown government sniper. Peltier barely escaped, and fled to Canada.

That scant description encompasses all that’s actually known about the incident beyond a reasonable doubt. There’s no concrete proof of who shot Coler and Williams, or how exactly it happened. We don’t know for sure which side shot first in the altercation, AIM or the FBI agents. We don’t know if the agents were actually trying to serve an arrest warrant for James Eagle, as they said, or if they just used the warrant as a pretext to enter the ranch for some other purpose. A cloud of confusion and uncertainty hangs over the events of June 26 to this day. And yet Leonard Peltier was convicted for these killings, and he now sits in an iron cage at the United States Penitentiary in Coleman, Florida.

The entire process of Peltier’s extradition, trial, and conviction was marked by a degree of official misconduct that seems incredible today. In the first place, a 1983 article in the Yale Law and Policy Review points out that the conditions of his extradition from Canada were highly questionable. To justify it, the U.S. government put forth three affidavits from a woman named Myrtle Poor Bear, who claimed that she’d been Peltier’s partner and heard him discuss plans to kill federal agents. But one of the affidavits contradicted the other two, saying that Poor Bear had left the Jumping Bull ranch before the shooting broke out, while the others said she had been present and actually seen Peltier pull the trigger. That alone should have been enough to get the supposed evidence thrown out, but Peltier was extradited regardless. At trial, the defense called Poor Bear to the stand—but the judge excused the jury so they wouldn’t actually hear her testimony. As the Yale Law Review puts it:

Poor Bear stated that she had never seen Peltier before the trial and that she had never lived in the Jumping Bull Compound. She explained that two FBI agents spent a considerable amount of time with her in February and March of 1976, and that the agents obtained the affidavits by threatening her with arrest, physical harm, and even death to herself and members of her family. According to her testimony, the agents took her to the Jumping Bull area at least twice and showed her a model of the scene in order to add credibility to the affidavits. Further, she testified that the affidavits were untrue, that she had never read them, and that she had signed them only under coercion and not in the presence of a notary.

Astonishingly, the judge found that this testimony of witness intimidation by the FBI was “immaterial,” apparently based on his opinion that Poor Bear was “unreliable.” But it was actually highly relevant. In the first place, if an extradition is illegitimate, it throws the jurisdiction of the court on shaky ground, since the defendant arguably shouldn’t be standing trial there in the first place. And in the second, it demonstrates that the federal government was willing to falsify evidence to prove their case against Peltier, which casts all their other evidence into doubt.((In 2000, Poor Bear officially retracted her affidavits, testified that she had never even met Peltier, and said that FBI agents threatened to abduct her child to make her say otherwise.))

The rest of the trial wasn’t much better. As Nick Estes points out, one of the jurors—a woman named Shirley Klocke—openly said during a coffee break that she was “prejudiced against Indians,” but was allowed to stay on the jury anyway. One key witness, an AIM member named Michael Anderson, testified that he’d seen Peltier carrying an AR-15 rifle, the same type of gun used to kill Coler and Williams—but then testified on cross-examination that he, too, had been threatened by an FBI agent before the trial, with the understanding that he would “get beat up if [he] didn't give him the answers that he wanted.” Another important part of the case hinged on the idea that only Leonard Peltier possessed an AR-15, out of everyone at the Jumping Bull ranch—but this, too, was never actually proven, and it’s since then been suggested that several other people had these guns. An FBI firearms expert, Evan Hodge, even testified that he hadn’t conducted a particular ballistic test on Peltier’s gun, only for it to later come out that he had conducted the test, with results that suggested it couldn’t have been the murder weapon. The whole prosecution was sketchy from top to bottom.

In 2021, James H. Reynolds—the federal prosecutor who handled Peltier’s case—wrote a remarkable letter to President Biden. In it, he admits that “We were not able to prove that Mr. Peltier personally committed any offense on the Pine Ridge reservation,” and says that “the prosecution and continued incarceration of Mr. Peltier was and is unjust.” He says Peltier was deemed “guilty of murder simply because he was present with a weapon at the Reservation that day,” and calls the verdict “a result that I strongly doubt would be upheld in any court today” based on the “minimal evidence” involved. Finally, he urges Biden to issue a clemency order to “take a step towards healing a wound that I had a part in making.” It’s rare for a former United States Attorney to urge the release of a prisoner he helped to put away, but Reynolds did it. That’s how bad the trial was, and how indefensible Peltier’s imprisonment is today.

Reynolds is far from the only prominent voice calling for Peltier’s freedom. Amnesty International, one of the world’s foremost human rights organizations, has considered Peltier a political prisoner since 2000, around the time they called on Bill Clinton to issue him clemency. Mary Robinson, the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights at the time, did the same. (Clinton, in typical form, ignored them both.) In 2009, Archbishop Desmond Tutu issued a statement urging Peltier’s release. At various points in the past, a long list of political and spiritual leaders including Nelson Mandela, Pope Francis, Coretta Scott King, and the Dalai Lama among others, have done the same—as have multiple former FBI agents, judges, members of Congress, Nobel laureates, and the United Nations Working Group on Arbitrary Detention. The ACLU and Human Rights Watch also wrote a joint letter to the U.S. Parole Commission this year, urging them to have mercy. The consensus is overwhelming.

You don’t have to believe Peltier is innocent of the killings to call for his freedom. The point is that the U.S. government failed to satisfactorily prove him guilty in a fair trial. The standard, in what we somewhat laughably call the “justice system,” is that one is innocent until conclusively proven guilty. Peltier was denied the basic rights of due process that everyone is entitled to. He did not receive an unbiased jury, a lawful extradition process, or a trial untainted by coerced testimony and dubious evidence. Thus, his continued imprisonment is not just an injury to him, and not just to Native Americans—who are already imprisoned at a wildly disproportionate rate compared to other groups—but to every other defendant in a U.S. court, and to the principle of justice itself.

Along with the legal dimension, though, there is also a grave moral one. Even if you believe Peltier did kill those FBI agents, it was nearly 50 years ago. In the intervening half-century, he’s suffered more than enough. He has several chronic health issues—including diabetes, high blood pressure, a life-threatening heart aneurysm, and severe jaw pain—that have been worsened by the wretched standard of medical care in U.S. prisons. Now, as he nears 80 years of age, it’s impossible to claim that his imprisonment is somehow necessary to protect the broader community. He’s not a threat to anyone or anything. Instead, it begins to look more like simple cruelty. In all likelihood, Peltier has only a handful of years to live, and it would be a great shame if he’s forced to spend them in a dismal cell as a result of something that happened in 1975. This is what the Pope, the Dalai Lama, and dozens of other advocates understand. It’s time President Biden and the Justice Department did too.

Free Leonard Peltier!

notes

1. This is the quick capsule version of events, by the way. A much fuller account can be found in Peter Matthiessen’s excellent book In the Spirit of Crazy Horse.