Do We Need a Second New Deal?

Revisiting the New Deal era offers crucial lessons in the current political moment. It shows how a distinctly American progressive politics might capture the support of a broad swath of the country and how major reforms can in fact be accomplished.

To go back and read Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s first Inaugural Address is a peculiar experience. It offers a glimpse of a world in which a Democratic president talked very differently than the Democrats of 2024 tend to talk. Elected in the depths of the Great Depression, Roosevelt used his first inaugural speech to promise a sweeping transformation of the country. He said the United States had been captured by “a generation of self-seekers” and that “unscrupulous money changers” (i.e., Wall Street) with “no vision” had plunged the country into catastrophe. But, he said, the plutocrats had been discredited, and society would be rebuilt:

The money changers have fled from their high seats in the temple of our civilization. We may now restore that temple to the ancient truths. The measure of the restoration lies in the extent to which we apply social values more noble than mere monetary profit.

“Depression” did not just describe an economic condition but a spiritual one, and FDR did not just come in with “liberal” policies but with a forward-looking vision that exhorted the country to have faith that its problems were soluble through unified national action.

He delivered. Let’s run through the familiar list of New Deal projects:

- The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC): Provided jobs for young men in conservation and natural resource projects.

- Public Works Administration (PWA): Funded large-scale public works like bridges, schools, and dams to stimulate the economy.

- Works Progress Administration (WPA): Employed millions in diverse projects, including construction and the arts.

- Social Security Act: Established pensions for the elderly and unemployment insurance.

- National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA): Regulated industries to promote fair wages and prices.

- Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA): Subsidized farmers to reduce crop production and stabilize prices.

- Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA): Brought electricity and economic development to the Tennessee Valley region.

- Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA): Provided direct relief and work relief to those in need.

- Securities Act of 1933: Mandated financial transparency in the issuance of securities.

- Securities Exchange Act of 1934: Established regulations for stock trading and created the SEC.

- Glass-Steagall Act (Banking Act of 1933): Separated commercial and investment banking to prevent financial instability.

- Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC): Insured bank deposits to restore public confidence in banks.

- National Labor Relations Act (Wagner Act): Guaranteed workers' rights to unionize and collectively bargain.

- Fair Labor Standards Act: Set minimum wage and maximum hours and banned child labor.

- Rural Electrification Administration (REA): Brought electricity to rural areas.

- Home Owners' Loan Corporation (HOLC): Helped homeowners refinance mortgages to avoid foreclosure.

- Federal Housing Administration (FHA): Provided insurance for home loans to make housing more affordable.

- Resettlement Administration: Relocated struggling families to planned communities.

- Civil Works Administration (CWA): Provided short-term jobs during the winter of 1933-34.

- Emergency Banking Act: Stabilized the banking system by closing and inspecting banks.

- Farm Security Administration (FSA): Supported rural poverty alleviation and migrant workers.

- Soil Conservation Service (SCS): Promoted soil conservation to combat erosion and improve agriculture.

- Federal Surplus Relief Corporation: Distributed surplus food and commodities to the needy.

- National Youth Administration (NYA): Provided work and education opportunities for young people.

- Federal Communications Commission (FCC): Regulated radio, television, and other communication industries.

- United States Housing Authority (USHA): Funded low-income housing projects.

- Federal Writers' Project: Employed writers to produce state guides, histories, and other works.

- Federal Theatre Project: Funded theater productions and performances nationwide.

- Federal Art Project: Supported artists to create public art and educational programs.

- Federal Music Project: Employed musicians to perform and teach music.

- Rural Rehabilitation Program: Aided impoverished rural families with loans, training, and resources.

Historian Harvey Kaye summarizes just some of the accomplishments in The Fight for the Four Freedoms: What Made FDR and the Greatest Generation Truly Great:

Employing 4.5 million people during the harshest months of 1933–34, the CWA "built or improved 500,000 miles of roads, 40,000 schools, over 3,500 playgrounds, athletic fields, and 1,000 airports." And affording work to a total of 8.5 million people between 1935 and 1943, the WPA of the ensuing "Second New Deal" would upgrade 600,000 miles of rural roads, lay 67,000 miles of city streets, erect 78,000 new bridges and viaducts, construct 40,000 public buildings, and build several hundred airports. Concurrently, the PWA would underwrite construction of thousands of miles of roadways and an equally remarkable number of public buildings and structures such as schools, libraries, hospitals, post offices, state and municipal offices, bridges, and water and sewer systems—35,000 projects altogether—including the Boulder, Grand Coulee, and Bonneville dams out west, the Lincoln Tunnel and Triborough Bridge in New York, Skyline Drive in Virginia, and the Los Angeles water supply system. The TVA would realize a dazzling scheme of dams, reservoirs, environmental works, and community enterprises providing hydroelectric power and economic development to the long-neglected people of the Tennessee Valley region. And the Rural Electrification Administration (REA), created in 1935, would in just a few years enable the formation of more than 400 local power cooperatives, bringing affordable electricity to nearly 300,000 farms and rural households that corporate utilities had refused to serve. FDR’s "public works revolution" dramatically enhanced the state of the public weal and—placing the needs of the commonwealth above those of corporations—rendered powerful testimony to the possibility of pursuing public action for the public good.

In a time when it takes a political fight to maintain even existing social programs, it’s hard to imagine the government taking this much decisive action, this quickly. The New Deal fundamentally changed Americans’ relationship with their government. It introduced the modern social safety net, and Roosevelt was so successful at cultivating public support for his project that he was elected more times than any other president, attained huge majorities in Congress, and was revered after his death.

As William Leuchtenburg writes in Franklin Roosevelt and the New Deal, “the devotion Roosevelt aroused owed much to the fact that the New Deal assumed the responsibility for guaranteeing every American a minimum standard of subsistence.” Never mind Ronald Reagan’s famous phrase that the scariest words in the English language are “I’m from the government, and I’m here to help.” Roosevelt said: the government should be and will be there to help, and he convinced Americans to have faith in him.

Partly, he did that by introducing programs with results that people could see. They could see the dams and bridges being built, the electric lines being strung, the millions of trees being planted, the art and theater productions. They got Social Security checks and affordable home loans. Their bank balances were guaranteed so that they didn’t have to fear bank runs. The Fair Labor Standards Act brought them a 40-hour workweek and (largely) got rid of child labor. They could see their government delivering for them, and, as a result, right-wing scaremongering about the New Deal as creeping authoritarianism was unsuccessful. As Michael Hiltzik writes in The New Deal:

The New Dealers did not think about government in the limited terms of their predecessors, as an agency of national defense and little else. They did not perceive it as an antagonist of the common man, an enemy of liberty, or an entity interested in its own growth for growth’s sake. They understood that it was a powerful force and that its power could be exercised by inaction as well as action, to very different ends.

Roosevelt believed it was his job to explain to people what their government was doing, and people trusted him in part because he spoke to them directly and plainly. In his press conferences, Roosevelt won over journalists with “good-humored ease and impressed them with his knowledge of detail.” In part through his use of the “fireside chats,” Roosevelt became “in a very special sense the people’s President,” as Justice William O. Douglas said, “because he made them feel that with him in the White House they shared the presidency. The sense of sharing the Presidency gave even the most humble citizen a lively sense of belonging.” Eleanor Roosevelt said that after his death, people told her they “missed the way the president used to talk to them. They’d say ‘he used to talk to me about my government.’” (Interestingly, the same quality explains some of Donald Trump’s appeal to his supporters.)

Of course, Eleanor herself was a major factor behind Roosevelt’s success. Theodore Roosevelt’s widow Edith had dismissed Franklin as “nine-tenths mush and one-tenth Eleanor,” and Mrs. Roosevelt was one of the most remarkable women of the 20th century. Through her newspaper columns, books, and speeches, she was herself an exceptional communicator of democratic ideals, and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights that she helped draft remains perhaps the clearest and most comprehensive vision for what a genuinely fair society would look like.

Illustration by C.M. Duffy

Illustration by C.M. Duffy

The New Deal programs did not fully end the Great Depression, although they did cut unemployment substantially and provide relief to millions. Interestingly, Roosevelt did not come into office with a sweeping plan, and on the campaign trail in 1932, he had often not sounded that distinct from his opponent, Herbert Hoover, in his promise to rein in government spending and adopt responsible budgets. Roosevelt had declared that he “regard[ed] reduction in Federal spending as one of the most important issues of this campaign.” But the only way to fulfill Roosevelt’s promise to deal aggressively with the suffering that had gripped the nation was to conduct what Roosevelt referred to as “bold, persistent experimentation,” and Roosevelt was swiftly forced to abandon his earlier promise to be fiscally conservative.

Some of those experiments failed, but some, like Social Security, were so spectacularly successful that 80 years of right-wing efforts to undo them have not succeeded. Dwight Eisenhower, a Republican, famously declared that core parts of the New Deal reforms had built such a lasting consensus that they simply could not be undone:

Should any political party attempt to abolish social security, unemployment insurance, and eliminate labor laws and farm programs, you would not hear of that party again in our political history. There is a tiny splinter group, of course, that believes you can do these things. Among them are [a few] Texas oil millionaires, and an occasional politician or business man from other areas. Their number is negligible and they are stupid.

Eisenhower was not wrong that they were stupid, and even today Republicans have to pretend not to despise Social Security. Roosevelt is routinely ranked by historians as among the greatest U.S. presidents, not just for his role in leading the country during World War II but for transformatively expanding the social safety net and giving people a new faith in what government was capable of doing for the people.

And yet the dark spots on FDR’s legacy are dark indeed, so much so that they virtually ruin the heroic image of him.

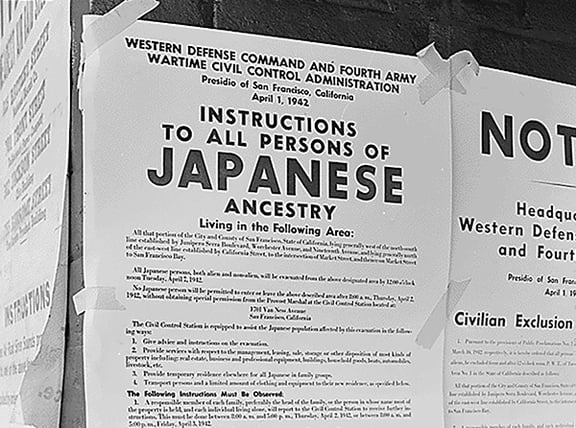

The internment of Japanese Americans in concentration camps was not some mere regrettable minor error. Roosevelt knew that there was no evidence that Japanese Americans were disloyal. He had commissioned a report which found a “remarkable, even extraordinary degree of loyalty among this generally suspect ethnic group.” But after Pearl Harbor, public opinion was harshly anti-Japanese, and instead of working to remind Americans that Japanese Americans were their neighbors, Roosevelt appointed a racist named John DeWitt to head a vast incarceration program. DeWitt told the newspapers “a Jap’s a Jap” and testified:

I don't want any of them here. They are a dangerous element. There is no way to determine their loyalty. It makes no difference whether he is an American citizen, he is still a Japanese.

Anyone who had at least one-sixteenth Japanese ancestry was put in a camp for the duration of the war, and many found when they were released that their property had been appropriated in their absence. The internment was so shameful that even George H.W. Bush, who famously said he would “never apologize for America,” apologized for America, supporting reparations and admitting that “serious injustices were done to Japanese Americans during World War II.”

It was not the only ugly act by Roosevelt. He continued Hoover’s policy of deporting large numbers of Mexican Americans to Mexico, including U.S. citizens. Infamously, he did not take even basic steps to rescue Jewish refugees from Hitler’s persecution. As Andrew Hollinger of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum explains, “[Rescuing Jews] was not a priority for President Roosevelt or virtually anyone else in the government. […] President Roosevelt led the effort to prepare America to enter the war, but never made rescuing the victims of Nazism a priority.” After Kristallnacht in 1938, Roosevelt “refused to criticize the leaders of Nazi Germany” and “did not issue a single statement critical of the Nazis during the first five years of Hitler’s rule” and “repeatedly compelled Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes to remove critical references to Hitler from his speeches.” Roosevelt “refused to support a bill that would have let 20,000 Jewish German adolescents into the U.S.” This was not because he harbored extreme Hitlerian anti-Jewish animus. Although he made some antisemitic remarks, he was generally strongly supported by American Jews and had many Jewish advisers. But for the most part he simply did not regard the fate of European Jewry as something America was obligated to do something about.

These details are often overlooked because of Roosevelt’s role in defeating Nazi Germany, as if it is petty to quibble over the shortcomings of a president who saved the world from Nazism (or at least helped the Soviet Union to do so). And it’s true that, as the authors of FDR and the Jews point out, “Roosevelt reacted more decisively to Nazi crimes against Jews than did any other world leader of his time,” which shows how low the bar was. They note that Roosevelt was in part making a political calculation that “the more Roosevelt risked on initiatives for Jews, the less he thought he could carry Congress and the public with him on broad issues of foreign policy.” But the failure of the United States to take meaningful action to prevent the Holocaust is a historic disgrace, and we should not set it aside out of a desire to preserve a heroic narrative of our own role in World War II, or a saintly image of Franklin Roosevelt.

There are other less extreme, but also disturbing, failings. The New Deal’s social safety net was not extended equally to Americans of all races. Infamously, agricultural and domestic workers were originally excluded from Social Security, and government loans were not available in Black neighborhoods. Roosevelt was, to put it charitably, not a bold leader on civil rights. He refused to support an anti-lynching bill in order to maintain the support of Southern Democrats on other issues, and it took pressure from A. Philip Randolph and the threat of a massive march for Roosevelt to issue an executive order prohibiting discrimination in the defense industry.

None of this is excusable. But nor does it negate the achievements of the New Deal agencies. There was perhaps more progress between 1929 and 1939 in advancing public welfare than in the first 300 years of American history. Roosevelt’s leadership helped save America and the world from fascism. He also managed it all despite having been paralyzed from the waist down since the age of 39, an extraordinary achievement that perhaps doesn’t get the awe it deserves because Roosevelt so carefully concealed his disability from the public.

Revisiting the New Deal era offers crucial lessons in the current political moment, when Democrats have spectacularly failed to offer a compelling alternative to Donald Trump’s right-wing authoritarian politics. We can see how a distinctly American progressive politics might capture the support of a broad swath of the country and how major reforms can in fact be accomplished.

Roosevelt, above all else, delivered. Apparently, there are some in Democratic circles who believe that Joe Biden practiced a form of politics known as “deliverism,” which focused on delivering tangible benefits to voters in the hope it would win their support. Well, that would be news to voters, few of whom could probably name a Biden policy that impacted them. Roosevelt showed people what their government was doing. He carved it in stone—here in New Orleans, “Built by the Works Progress Administration” is still etched into the bridges of beautiful City Park. And he took to the radio to explain to them what he was doing so that they could understand his project. Any president or party who wants to be successful should take that key lesson from Roosevelt: give people things they can see and feel, and then tell them you’ve given it to them. (When Donald Trump’s administration sent out stimulus checks to Americans during COVID, for instance, Trump made sure his name was on them.)

Importantly, the New Deal did not just give monetary handouts. It also fostered culture and belonging. The Federal Theater Project, for instance, was shut down prematurely in 1939 after anti-communists waged a witch hunt against it over the subversive themes of its productions. (Its director was asked in a hearing of the House Un-American Activities Committee whether Christopher Marlowe was the name of a communist.) But in its short life it made the theater accessible to countless Americans and was a starting point for major artists like Arthur Miller and Orson Welles. Theater critic Brooks Atkinson said the project “kept an average of ten thousand people employed on work that has helped to lift the dead weight from the lives of millions of Americans” and that it “has been the best friend the theatre as an institution has ever had in this country."

WPA art has become legendary and still adorns many federal buildings. Roosevelt said of the government funded art: “some of it [is] good, some of it [is] not so good, but all of it [is] native, human, eager, and alive—all of it painted by their own kind in their own country, and painted about things that they know and look at often and have touched and loved.”

Reviewing the New Deal generation’s accomplishments, Harvey Kaye writes that those of us living in the United States of the 21st century should be proud of what our forebears did:

Most of all we need to remember that we are the children and grandchildren of the men and women who accomplished all of that—in the face of powerful conservative, reactionary, and corporate opposition, and despite their own faults and failings—by making America freer, more equal, and more democratic than ever before. Now, when all that they fought for is under siege and we, too, find ourselves confronting crises and forces that threaten the nation and all that it stands for, we need to remember that we are the children and grandchildren of the most progressive generation in American history. We are the children of the men and women who articulated, fought for, and endowed us with the promise of the Four Freedoms.

For Kaye, Roosevelt’s idea of the Four Freedoms—freedom of speech, freedom of worship, freedom from want, and freedom from fear—was a powerful vision that helped Americans understand, at a time when fascist governments were taking hold around the world, what we should be fighting for. Kaye also points to Roosevelt’s “Second Bill of Rights” proposal, which would have guaranteed people employment, income, housing, healthcare, and education, as an agenda worth reviving and embracing. Roosevelt had a clear understanding of what government ought to be doing for people and thereby gave a convenient, easily remembered way for people to measure the performance of their public servants. Are we free of want? Clearly not, in a country with widespread homelessness, economic precarity, food insecurity, and other forms of easily preventable misery. Then we are not yet free.

Roosevelt, of course, took office amidst a catastrophe. What the New Dealers accomplished was only possible because the previous administration had been utterly discredited in its failure to deal with a serious crisis. Does it take a disaster to make a visionary social democratic politics possible? Let us hope not. But that can’t be proven either way. What we do know is that the New Deal era shows us a possible way out of the political dead end the Democratic Party has reached. Leftists often argue, perhaps rightly, that Rooseveltian social democracy helped neutralize revolutionary currents and “save” capitalism. (Roosevelt himself said that “It was this administration which saved the system of private profit and free enterprise after it had been dragged to the brink of ruin.”) But few today would wish for a world without Social Security. And every leftist can benefit from studying how an administration can win popular support through providing tangible gains and demonstrating leadership that builds public confidence. If we are to come back from and reverse Trumpism, it may require a Second New Deal.