Did Bob Dylan Betray Left Politics?

The new Dylan biopic "A Complete Unknown" examines the singer’s shift away from the political folk scene and into rock-and-roll stardom. It underlines the difficult tension between using art for political force and individual expression.

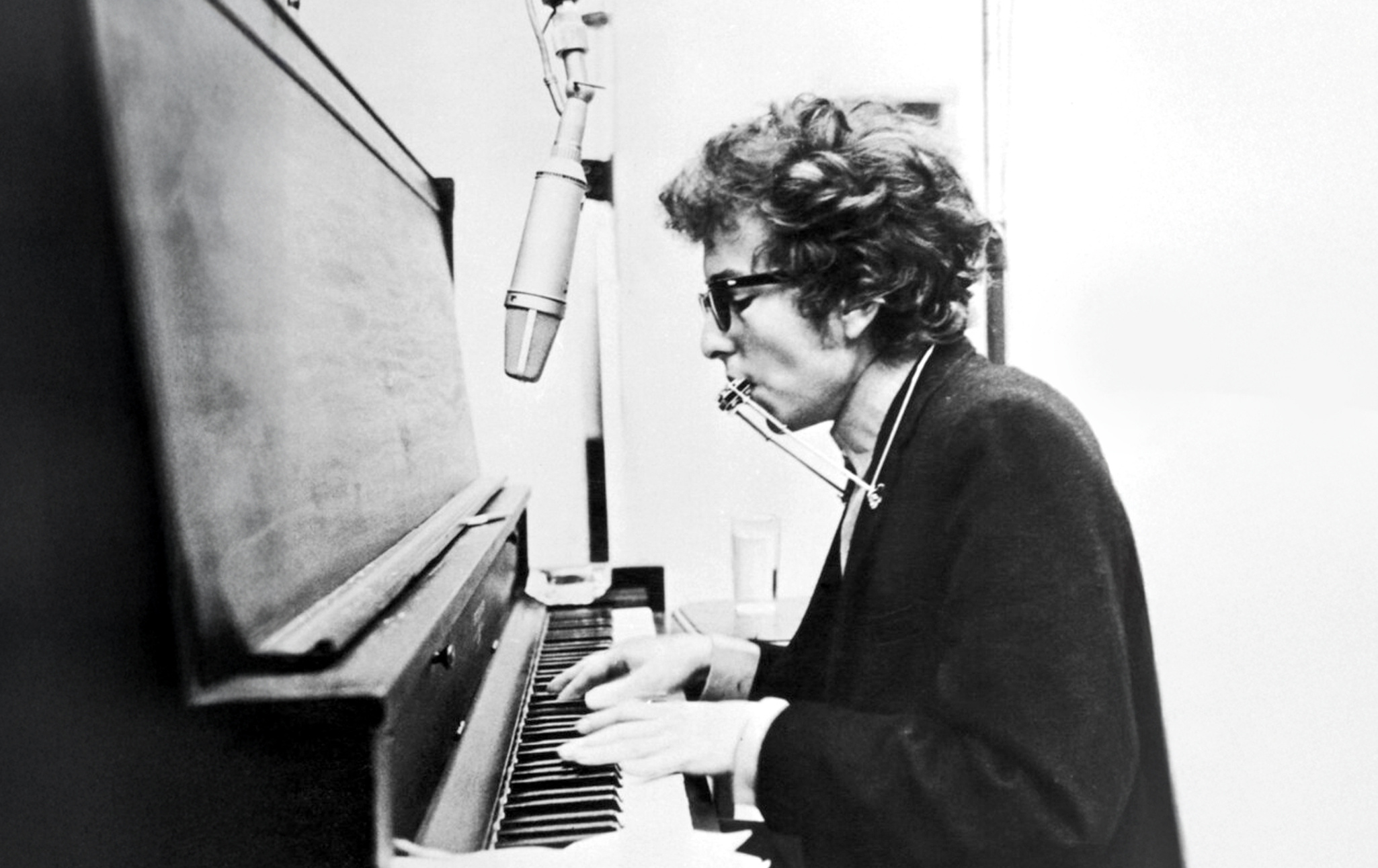

To call A Complete Unknown, the Bob Dylan biopic that released this past Christmas, a “film” in the proper sense feels a bit imprecise. It’s essentially a two-and-a-half-hour Dylan tribute show structured loosely by a series of scenes from the singer’s early career. It provides the Wikipedia bullet points of one of the most heavily researched and pored-over chapters in the history of rock ‘n’ roll: Dylan’s infamous performance at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival.

The film explores Dylan’s early career, beginning with his sojourn from small-town Minnesota to New York to visit his ailing idol Woody Guthrie in the hospital. It follows him as he becomes a beloved acoustic balladeer and the centerpiece of a protest folk scene that was ascendant amid the radical social change of the early 1960s. But at the height of his powers as a revered countercultural icon and “spokesman of a generation,” Dylan makes a radical shift in his sound and his lyrical approach, ditching his acoustic guitar for a Stratocaster and his topical songs about the injustices of the day for ones that were much more idiosyncratic and individualistic.

The climax of the film takes place on a fateful July night in Newport, where Dylan debuted his new sound in front of a throng of folk music fans who’d expected to be roused with the acoustic civil rights and anti-war anthems they’d come to revere him for—songs like “The Times They Are A-Changin,” “Blowin’ in the Wind,” and “When the Ship Comes In.” Instead, he strode to the stage in a leather jacket, with a full backing band, and delivered a plugged-in set that left many in the crowd stunned and angry. As the film depicts, many onlookers booed and jeered, leading Dylan to exit the stage after just three songs. He departs Newport alone on his motorcycle and spiritually departs the folk scene that brought him to stardom.

A Complete Unknown largely treads through the beats of this well-known saga without much effort to understand Dylan’s inner monologue during this pivotal point in his career. As a lifelong admirer of Dylan’s music, I still found the film thoroughly enjoyable, in no small part due to the titanic performance of Timothée Chalamet, who not only spent five years learning to play the guitar in anticipation of the role but almost uncannily mimics Dylan’s nasal drawl. But if you come expecting a definitive answer about what motivated Dylan’s fateful decision to change his sound, you will be left wanting. (Perhaps going into a film titled A Complete Unknown expecting to come out knowing things is your own mistake.) That said, the film does raise some important questions about the uneasy relationship between activism and artistic expression, and about the unique challenges that can arise when an artist tries to simultaneously serve a social or political “movement” and themselves.

The film depicts Dylan as a chimeric trickster god who can only be witnessed, not understood. Despite the fact that we follow him for the entire movie, we never get a real glimpse into what motivated him to write some of the defining pieces of music from his era. Rather, we experience him at a distance alongside the people who knew him best. We see “Sylvie Russo,” Elle Fanning’s stand-in for Dylan’s real-life girlfriend, Suze Rotolo, shepherding him into the political struggles of the time. At one point she brings him to a meeting of the Congress for Racial Equality, which is shown to have been an inspiration for his music about the civil rights struggle. (Rotolo, in real life, was an underappreciated inspiration for Dylan’s early protest music. In her obituary, the Guardian credits her with having “schooled Dylan in the politics of the left and [...] first made him aware of the labour and civil rights movements.”)

We see his relationship and musical collaboration with Joan Baez, who, despite an exceptional performance by Monica Barbaro, is mostly relegated to the status of a love interest for Dylan, and who sits around being amazed and/or infuriated by the singer’s eccentric genius. At one point, he shows up unannounced at her apartment in the middle of the night after they’ve broken up just so she can watch him write a song before she kicks him out. By contrast, the most fleshed out of Dylan’s relationships depicted in the film is the one he has with Pete Seeger, whose performance by a perfectly reedy and upright Ed Norton is my favorite in the film. The iconic singer, socialist activist, and steward of a nascent folk revival is shown seeking to mold the scruffy vagabond Dylan into an ideal successor to spread his social gospel.

Seeger’s life as a performer and his life as a political spokesman were deeply intertwined. As Elijah Wald writes in his book Dylan Goes Electric!, upon which the film is loosely based, “Seeger always preferred to think of himself as a conduit, proselytizer, and catalyst rather than as a star.” Along with Woody Guthrie, Lee Hays, Lead Belly, and other artists, Seeger spent much of the 1940s barnstorming the country, playing picket lines and union halls, before settling in Greenwich Village. There, he and other leftist musicians became known for hosting raucous singing parties that came to be known as “hootenannies.” In a recent Current Affairs article about the joys of hootenannies, Annie Levin described how they functioned dually as a means of social gathering and a means of organizing. She quotes Seeger, who wrote in his book The Incompleat Folk Singer that “Ultimately, rank-and-file participation in music goes hand-in-hand with creativity in other planes—arts, sciences, and yes, even politics.”

The Greenwich hootenannies were Seeger’s effort to build an organization called People’s Songs, which wrote, performed, and disseminated “topical” music that promoted the labor movement and challenged war and racism while dispatching singers to perform at progressive benefit shows. The word “hootenanny” would come to be associated with radicalism, and Seeger was banned from advertising them in the New York Times as a result. But Seeger and the folk revival movement continued to grow in popularity, culminating in his group, the Weavers, charting No. 1 with a cover of Lead Belly’s song “Goodnight, Irene” in 1950. This was an astounding moment for a folk scene that had long remained niche, but it would prove an apogee. Seeger and his fellow travelers would be driven underground by the rise of McCarthyism and the anti-Communist blacklist. “About two years later,” Seeger said, “instead of singing in the Waldorf Astoria or Ciro’s in Hollywood, we were singing in Daffy's Bar and Grill in the outskirts of Cleveland and decided to take a sabbatical.”

In 1961, when Dylan hitchhiked into Greenwich Village, Seeger was in the process of rebuilding a movement that had been ripped apart by the forces of reaction. In the aftermath of the Red Scare, there were fewer picket lines at which to sing. But there were also new struggles against racism and militarism that were galvanizing young people the nation over.

By the time July 1965 had rolled around, the war in Vietnam was ratcheting up. On the morning before Dylan walked on stage at Newport, the New York Times reported that President Johnson—who’d already dramatically expanded the war in the past year and launched a brutal bombing campaign in February—had plans to double the military draft. And despite the folk scene’s broad unity on civil rights, in 1965, there was nothing near a consensus about the war. While Seeger and others like Phil Ochs stridently opposed it,1 other folk musicians were skittish about addressing it, fearing it would undermine their increasingly mainstream civil rights message or hurt their business.

In an environment where Seeger was struggling to keep the folk scene a clear-eyed political force, it must have felt like Dylan was the last remaining block that, if removed, could topple the entire Jenga tower. Here was somebody who could captivate a crowd at Carnegie Hall with long, stirring musical sermons. Someone who wouldn’t just render America’s fear of nuclear holocaust, but do so with stark imagery, singing on “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall” of “a young woman whose body was burning,” “a highway of diamonds with nobody on it,” and of a place “where black is the color and none is the number.” Someone who wouldn’t just call for the cannonballs to be “forever banned” but call out the “masters of war” getting rich from their destruction. Someone who wouldn’t just gesture at the injustice and violence wrought upon Black Americans like Emmett Till, Medgar Evers, and Hattie Carroll, but point out that even the perpetrators of that violence were being used as a “pawn in the game” of the powerful to destroy cross-racial solidarity. He was willing to perform those songs at a voter registration drive in Greenwood, Mississippi, while staring down racist cops and Klansmen. Dylan was a once-in-a-generation talent, and for someone like Seeger who believed in his marrow that folk music was an agent of societal change, losing him was not an option.

In the film, Seeger explains his mission and how Dylan fits into it in stark terms. He tells a parable (one he often told in real life) about what he called “teaspoon brigades”:

Imagine a big seesaw. One end of the seesaw is on the ground because it has a big basket half full of rocks in it. The other end of the seesaw is up in the air because it’s got a basket one-quarter full of sand. Some of us have teaspoons, and we are trying to fill it up. ‘Most people are scoffing at us. They say: “People like you have been trying for thousands of years, but it is leaking out of that basket as fast as you are putting it in.”

‘Our answer is that we are getting more people with teaspoons every day. And we believe that one of these days or years – who knows – that basket of sand is going to be so full that you are going to see that whole seesaw going “Zoop!” in the other direction.

Dylan—an artist who had achieved mass success while preaching an unflinching egalitarian vision—had, as Seeger put it, “brought a shovel.”

This critical context for the events portrayed in the film is nevertheless pushed to the sidelines. Director James Mangold portrays the Newport controversy as one that was primarily about Dylan’s change in musical direction—his abandoning of rousing acoustic ballads for surlier, more lyrically ambiguous rock songs like “Maggie’s Farm” and “Like a Rolling Stone.” Many fans complained about the change in style. (They also complained that the set itself sounded terrible on account of the folk festival’s sound system being unable to accommodate loud electric instruments.) But there’s evidence that, especially among his fellow folk singers, the feelings of betrayal ran deeper. As Newport talent coordinator Jim Rooney put it in a letter to the festival board:

Pete [Seeger] began the night with the sound of a new-born baby crying and asked that everyone sing to that baby and tell it what kind of a world it would be growing up into. But Pete already knew what he wanted others to sing. They were going to sing that it was a world of pollution, bombs, hunger, and injustice, but that PEOPLE would OVERCOME. And many people did sing that way. That baby was given hope.

Then came Dylan’s explosion of light, sounds, and anger. . . . The tone of the evening had vanished. Hope had been replaced by despair, selflessness by arrogance, harmony by insistent cacophony.

“The people” so loved by Pete Seeger are the mob so hated by Dylan. In the face of violence he has chosen to preserve himself alone. ... And he defies everyone else to have the courage to be as alone, as unconnected, as unfeeling toward others, as he. He screams through organ and drums and electric guitar, “How does it feel to be on your own?” And there is no mistaking the hostility, the defiance, the contempt for all those thousands sitting before him who aren’t on their own. Who can’t make it. And they seemed to understand that night as for the first time what Dylan had been trying to say for over a year—that he is not theirs or anyone else’s.

It’s tempting, in light of how Dylan would go on to dismiss protest music following his rock success, to view him as a shameless opportunist who never truly believed in any of the ideals he preached and merely latched onto an ascendant folk scene to launch his career as a rock star. If he was trying to avoid that perception, he certainly didn’t do himself any favors. An interview he gave to Nat Hentoff in Playboy in February 1966, a year after the disastrous Newport performance, is particularly infamous.

Hentoff asked him if he believed he had any responsibility to young people who looked up to him as a kind of folk hero. He responded:

I don't feel I have any responsibility, no. Whoever it is that listens to my songs owes me nothing. How could I possibly have any responsibility to any kind of thousands? What could possibly make me think that I owe anybody anything who just happens to be there? I've never written any song that begins with the words "I've gathered you here tonight . . ." I'm not about to tell anybody to be a good boy or a good girl and they'll go to heaven. I really don't know what the people who are on the receiving end of these songs think of me, anyway.

When asked why he’d abandoned “message” songs and whether he’d lost interest in protest, the following exchange occurred:

DYLAN: I just didn't have any interest in protest to begin with… You can't lose what you've never had. Anyway, when you don't like your situation, you either leave it or else you overthrow it. You can't just stand around and whine about it. People just get aware of your noise; they really don't get aware of you. Even if they give you what you want, it's only because you're making too much noise. First thing you know, you want something else, and then you want something else, and then you want something else, until finally it isn't a joke anymore, and whoever you're protesting against finally gets all fed up and stomps on everybody. Sure, you can go around trying to bring up people who are lesser than you, but then don't forget, you're messing around with gravity. I don't fight gravity. I do believe in equality, but I also believe in distance.

HENTOFF: Do you mean people keeping their racial distance?

DYLAN: I believe in people keeping everything they've got.

This would seem to be a smoking gun, wouldn’t it? It sure sounds like Dylan is not just dismissing protest songs as an effective tactic, but the idea of protesting anything at all. A sense of defeatism might be understandable at this point in time. After all, all the protest songs in the world had done nothing to slow down the destruction of Vietnam. But Dylan also seems to have been saying that inequality is as fundamental to the natural world as “gravity,” something that isn’t even worth taking the time to fight. Dylan said he still believed in “equality,” but that’s obviously irreconcilable with “people keeping everything they’ve got.” Of course, it shouldn’t be ignored that Dylan, who’d reached peak levels of rock stardom and acclaim, had a lot more to “keep” than he did when he was the darling of a marginal folk scene.

Noam Chomsky recalls hearing Dylan speak on the radio around this time, saying something similarly dismissive when asked his thoughts on the Berkeley Free Speech movement:

DYLAN: Well, I have free speech, you know... I... I don't have those problems that they have. I don't really have to put up with any teachers, you know, or I don't have to have any degree. I don't have to take any tests. I don't have to sort any kind of philosophies out in my mind. I don't have to memorize anything, you know. I don't have, you know, to look like the next person. I don't have to, uh... I just don't have these problems.

Two years later, he would put it more plainly. When asked by Seeger’s magazine Sing Out! whether he’d “have to take some kind of a position” on the student and Black militant movements of the day, he flatly responded, “No.” This was a pretty frank admission that he no longer believed he had any obligation to use his music to take political stances.

Chomsky concluded that “If the capitalist PR machine wanted to invent someone for their purposes, they couldn’t have made a better choice.” The implication here is that Dylan’s radicalism was a pure media contrivance from the start—that he served his function as someone who could harness genuine disaffection and channel it away from collective struggle and towards solipsism.

Chomsky would probably tell me not to be so naive, but I simply struggle to believe that someone could have ever written a song as piercing as, say, “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll,” a song about a white Maryland socialite who senselessly beat to death his Black housekeeper and was handed a “six-month sentence,” without a genuine rage in his heart about the injustices faced by Black Americans. Likewise, I doubt that he could have, or would have, written a song like “Masters of War,” which flatly tells war profiteers “I hope that you die and your death will come soon,” unless he truly meant it—especially given the still very real risk of being blacklisted as a Communist subversive. Just two years before “Masters of War” was released, Seeger had been sentenced to a year in prison for refusing to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee over his “subversive” music (although the sentence was later reversed), and he still remained effectively banned from appearing on network television, which meant that his Rainbow Quest variety show was condemned to the limited viewership of public access TV.2 If Dylan was truly just a careerist, writing music that so stridently condemned American militarism is a risk that he probably would have been reluctant to take.

But secondly, and more importantly, interviews with people who knew Dylan at the time show him to have been someone genuinely moved by the topics he wrote about. In the 2005 documentary No Direction Home, Mark Spoelstra, another folk singer-songwriter who played with Dylan during his time in Greenwich Village, recalls that at the height of the Civil Rights Movement…

He had a great desire to change the world. We even talked about it. We thought that segregation wasn't going to last, and that we were going to have something to do with ending it. We really believed we were going to have a part as songwriters in changing the world.

But Dylan would probably be the first to admit that he was never very politically sophisticated. Of Seeger, he said, “I didn't realize he was a communist. I really wasn't sure even what a communist was. You know, if he was, it wouldn't have mattered to me anyway. I really didn't think about people in those terms.”

A mentor of Dylan’s, guitarist Dave Van Ronk, who was also a prolific socialist organizer, described him as a “populist”:

He was tuned in to what was going on—and much more than most of the Village crowd, he was tuned in not just to what was going on around the campuses, but also to what was going on around the roadhouses—but it was a case of sharing the same mood, not of having an organized political point of view.

Even when he performed “Blowin’ in the Wind” at the March on Washington, he remarked, “This here ain’t a protest song or anything like that, ’cause I don’t write protest songs… I’m just writing it as something to be said, for somebody, by somebody.”

Dylan’s drift away from what he called “finger-pointing” music seems to have had less to do with a change in his political convictions and more to do with a broad skepticism of being part of any larger movement or institution or being seen as a moral arbiter.

This discomfort comes across in another interview Dylan did with Hentoff, then working for the New Yorker, in 1964 about his discomfort with being given an award by a progressive group, the National Emergency Civil Liberties Committee.3 “I agree with everything that’s happening,” he said of the civil rights movement, “but I’m not part of no Movement. If I was, I wouldn’t be able to do anything else but be in ‘the Movement.’ I just can’t have people sit around and make rules for me. I do a lot of things no Movement would allow.”

He felt similarly constrained by the requirements of political folk music: “Those records I’ve already made, I’ll stand behind them, but some of that was jumping into the scene to be heard and a lot of it was because I didn’t see anybody else doing that kind of thing,” he told Hentoff. “Now a lot of people are doing finger-pointing songs. You know—pointing to all the things that are wrong. Me, I don’t want to write for people anymore. You know—be a spokesman.”

Nevertheless, that role of spokesman was being thrust upon him. In February 1964, about two weeks after the release of his album The Times They Are a-Changin’, he appeared on the Steve Allen Show. The host read Dylan—then a baby-faced 22-year-old—a series of articles that had been written about him. San Francisco Chronicle music critic Ralph Gleason described him as “A singing conscience and moral referee, as well as a preacher.” Billboard wrote that “Dylan’s poetry is borne of a painful awareness of the tragedy that underlies the contemporary human condition.” You can see on Dylan’s face that he’s a bit shaken up by this, unable to look up.

I’m a few years older than Dylan was then. I still found it totally overwhelming when, a couple of weeks ago, a Current Affairs article I wrote about Elon Musk got a couple of million views and over a thousand comments on Reddit, which is by far the most eyeballs any of my work has ever gotten. Don’t get me wrong, it was exciting. But it also made me keenly aware of myself as someone with an audience that was actually paying attention to the words I wrote, taking them seriously, and using them to inform themselves. I was proud, but a part of me also wanted to crawl under my bed and stay there for about six months. Then I thought about the fact that the number of people hanging onto my words is a fraction of a fraction of the number who were hanging onto Dylan’s. I can only imagine what it must have felt like, at age 22, to suddenly be appointed moral arbiter for the entire nation.

Now, as somebody who’s chosen to write articles yapping about politics for a living, I think I’ve forfeited any right to complain when people expect to hear my opinions on things or take the things I say seriously. I obviously have a “responsibility” to those who read my thoughts. And I personally feel that Dylan comes off rather petulant when he acts scandalized by the idea that people might actually care what he has to say. But I still can see where he’s coming from when he attempts to recuse himself from his role as a political totem:

DYLAN: Now, I hate to come on like a weakling or a coward, and I realize it might seem kind of irreligious, but I'm really not the right person to tramp around the country saving souls. I wouldn't run over anybody that was laying in the street, and I certainly wouldn't become a hangman. I wouldn't think twice about giving a starving man a cigarette. But I'm not a shepherd. And I'm not about to save anybody from fate, which I know nothing about.

This seems, more than anything, to be what made the Dylan view of music and the Seeger view of music incompatible. It’s a rather crude way of putting it, but Dylan is essentially right that “tramping around the country saving souls” is exactly what Seeger wanted to do. He wanted to celebrate folk traditions and help people experience collective joy, but first and foremost, music was his tool for political evangelism. That is something desperately needed, but it’s also not for everyone.

Many decades later, Kendrick Lamar went through a similar cycle after his 2015 song “Alright” became the unofficial anthem of the Black Lives Matter movement after the police killing of Sandra Bland. The public and the media appointed him a similar sort of spokesperson for his generation as they had Dylan, and he found the role too much to bear, going on a five-year hiatus from releasing music and remaining silent on political matters, including the nationwide protests following the murder of George Floyd. When he finally returned with a new album, it included the track “Savior,” a broadside against the idea that he or any other Black celebrity was responsible for giving moral guidance to their fans:

Kendrick made you think about it, but he is not your savior

Cole made you feel empowered, but he is not your savior

Future said, "Get a money counter", but he is not your savior

'Bron made you give his flowers, but he is not your savior

He is not your savior

Likewise, Dylan was willing to let politics be an inspiration for his music, but was not willing to take on the responsibilities that having real political convictions required. In his prolific early days, he and his girlfriend Suze Rotolo would often scour through newspapers simply seeking topics for him to write about. He told a Canadian interviewer: “I’m not politically inclined. My talent isn’t in that area; it’s just to play music. As it is, it falls into areas where people are politically motivated… ‘Blowin’ in the Wind’ was just a feeling I felt because I felt that way.” Once politics ceased to be a source of inspiration and became a pair of handcuffs that kept him from evolving as an artist, he began to instinctively rebel against any notion that he was ever a “political” songwriter at all.

I would argue that from a purely creative standpoint, exiting the narrow box of “protest music” freed Dylan to be a much more dynamic songwriter than he otherwise would have been, though we can’t truly know what he would have produced had he maintained his convictions. On a purely artistic level, accepting a less political Dylan was worth it if it meant we got to hear his surrealist epic poem “Desolation Row,” his inscrutable love ballad “Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands,” his genre pastiches like Nashville Skyline, his messy yearning divorce album Blood on the Tracks, and even some cuts from his much-maligned Born Again Christian phase like the introspective “Every Grain of Sand.”

And when he did periodically dive back into social commentary for songs like “George Jackson,” (a tribute to the Black Panther leader killed by prison guards at San Quentin), “Hurricane” (which called out the wrongful, racially-motivated murder conviction of boxer Rubin “Hurricane” Carter), and “Blind Willie McTell” (which reflects on how the Jim Crow era intertwined with the creation of Blues), it comes off like something that Dylan was writing about because he felt genuinely outraged by the injustice and not because it was his duty as a political spokesman.

We can still only guess what was truly in Dylan’s heart when he was composing the soundtrack to the radicalism of the 1960s. Whether he was an idealist who became jaded or a cynic from the start is probably something that will be debated and dissected from now until eternity. To some degree, it doesn’t matter, because the music will always be there. And while Newport symbolically marked the end of Dylan’s phase as primarily a political songwriter, that’s how many people still remember him. Dylan’s political songs will always define him, whether he wants them to or not. As Phil Ochs told Broadside magazine, “I don’t think he can succeed in burying them. They’re too good. And they’re out of his hands.”

1. As Dylan strayed away from protest music, Ochs—who remained on the straight-and-narrow with songs like “I Ain’t Marchin’ Anymore” and “Draft Dodger Rag” —would be christened by some as an “anti-Dylan,” who’d remained pure of heart. This was a label Ochs firmly rejected, even telling the Village Voice, “There’s nothing noble about what I’m doing. I’m writing to make money. I write about Cuba and Mississippi out of an inner need for expression, not to change the world.”

2. The FBI also snooped on Seeger for more than two decades and amassed a file of nearly 1,800 pages on every minuscule activity he undertook, though Dylan would not have known about this at the time.

3. This was a similar group to the ACLU that disagreed with its lackluster defense of the free speech rights of accused Communists during the McCarthy era.