How 'Don't Look Up' Powerfully Exposed the Absurdity of Climate Inaction

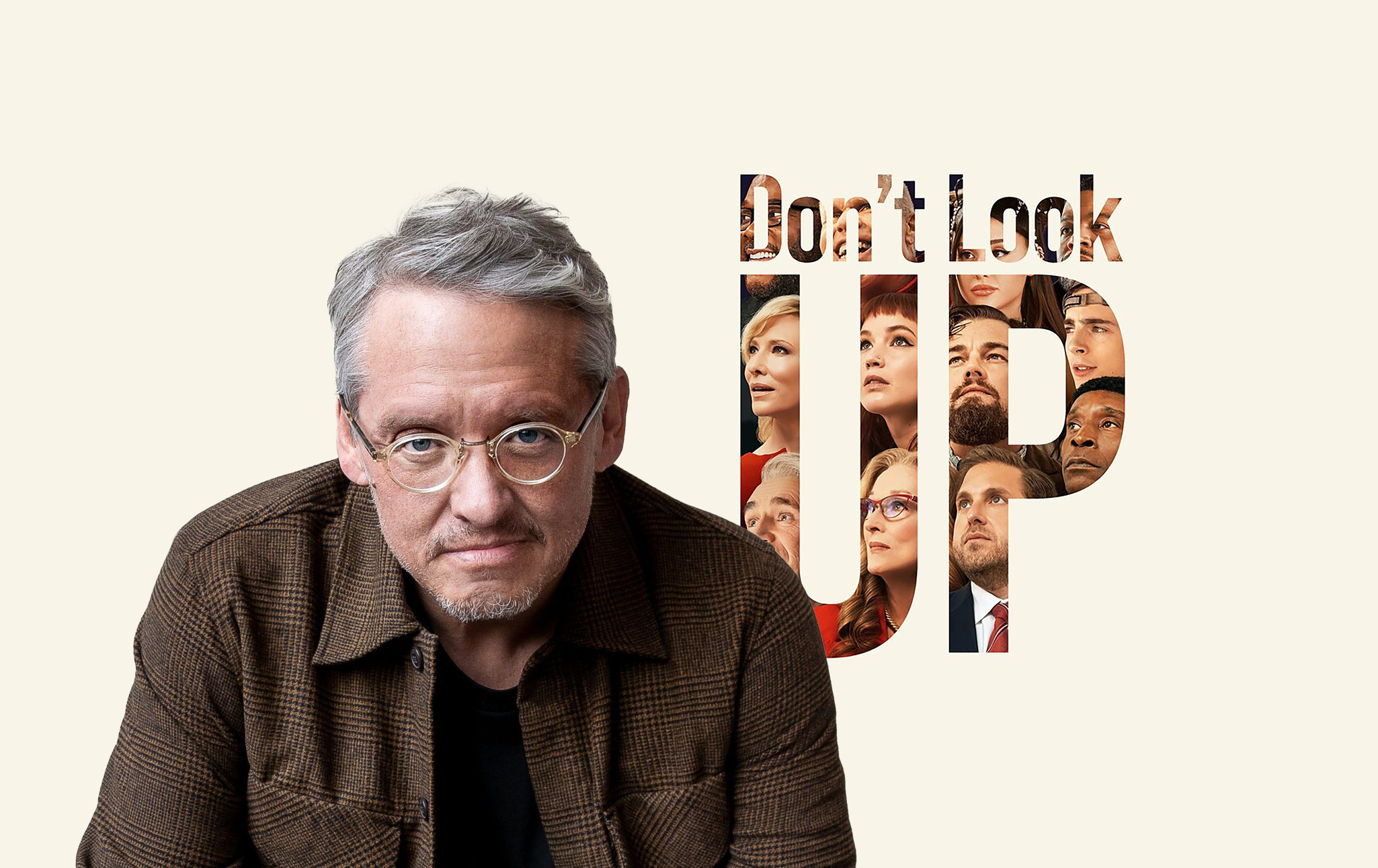

Filmmaker Adam McKay discusses the reaction to 'Don't Look Up,' the 2021 film which used satire to demonstrate the madness of our political response to the climate crisis and the media's role in climate denialism.

Adam McKay is a writer and film director who has made some of the most successful comedy films of our century, including Anchorman (No. 6 on Time Out's top 100 comedy films of all time), Talladega Nights, Step Brothers, and The Other Guys. In the last decade, his more dramatic and political films like Vice and The Big Short have attracted critical acclaim and been nominated for multiple Academy Awards. He joins us today to discuss the film he released in 2021, Don't Look Up, a satirical look at the climate catastrophe that uses the analogy of an approaching deadly comet to expose how the media, corporations, and the political system are incapable of addressing a major crisis. When Don't Look Up came out, it quickly became one of the most popular movies in Netflix's history, but many critics assailed it as "heavy-handed." In Current Affairs, Nathan wrote an article arguing that these critics were missing much of the penetrating leftist analysis that makes the film a remarkably astute piece of satirical fiction.

Today Adam joins to talk about Don't Look Up: what the film was saying about our world, what Adam hopes the audience gets out of it, what critics didn't get, and why the film should get us talking about the climate crisis itself rather than just analyzing the film.

Nathan J. Robinson

It was so funny—when Don't Look Up came out in 2021, I stupidly didn't want to see it because I had read reviews of it that described it as an obvious and heavy-handed satire. And I don't like obvious and a heavy-handed satire, so I thought, well, I'll give that a miss. But then it was Christmas, and my parents and I needed something to watch. We watched Don't Look Up, and I realized immediately that not only was it not "obvious," but the reason that the critics were saying it was "obvious" was that they'd missed a lot of things, which clearly proved that those things weren't obvious. But it was three years ago, so perhaps you could introduce us—reintroduce us—to the film, in case people haven't watched it in a little bit.

Adam McKay

It's a pretty good representation of how I was—and, sadly, still am—engaging with the world. The film toggles between a broad farcical comedy and a really dark tragedy. Those seem to be the two genres that we're living in these days. And I knew that I wanted to make a big film that was a world movie. Because of Netflix, we had an opportunity to go on a platform that has viewers from all over the world. So the big thing was, can you do comedy that plays in Nigeria, Vietnam, Brazil, the States, India, Pakistan?

So, yes, we made this big, broad, insane comedy that's also a really painful, emotional tragedy. And we got these incredible actors, and we went to launch the movie. It's well publicized that the reason I wrote it, and we made it, is because I was so disturbed by not only the lack of the action about the climate emergency—the seismic global climate emergency that we're in—but I was also noticing people were barely even talking about it. And so, one of the big purposes of the movie, in addition to the film itself, was the kind of media marketing tour that went around it.

So when anyone ever asks me what the experience of releasing the movie was like, I always tell this story, and it's the very first kind of “media hit” that we had. It was a big profile for a big name magazine, and the guy who was going to write it came into town, and right away I said to him, you're probably wondering, how did I get so disturbed about the climate? He goes, "No, it's just a midlife crisis thing, I don't care about that." And I was like, "Oh no," and I wouldn't let it go. I was like, "We can talk about my childhood and the stuff I've done, but here's the actual data, and here are actual statements from scientists." I emailed them to him, and he just didn't respond.

And at first, I thought, "Well, maybe this is one interview"—it was a big piece. It was the first thing we were doing. And then at the very end of our two days together, he clearly had dug up some little piece of dirt about Will Ferrell and me when we split up. The dirt didn't even really make sense. It was something about after we had split up, where I hadn't called Ferrell about something. I was kind of blindsided by it, and at that moment, I realized, "Oh, this is all he's been thinking about."

And I loved working with Ferrell. I worked with him for two decades. So I just said, "Yes, I should have called him. I screwed up." But it was after we broke up, and then the article came out. And instead of, "why is this guy freaking out about the climate?" there were like 200 articles about how I knifed the guy who played Buddy the Elf in the back.

Robinson

It's nice when the thesis of the movie is confirmed by the media reaction to it. But it's also really depressing. The audience reaction was very positive. Obviously, it became the most viewed Netflix film. As you said, you did succeed in getting it seen around the world, or getting it talked about. But when the reviews came out, often they were like, is it subtle enough? Well, who cares? I think of it as a piece of sociology, explaining how power works and why certain things happen, how the media works and how the state works—the various interests that people have, the way that people can be misled, and the factors that keep us from being able to come together to solve an existential problem. And so you want to ask, what are those things? And then they go, "tell us more about you and Will Ferrell." It’s like, who cares?

McKay

It was wild. The whole media tour and reviews were about how the film was not subtle enough, and "What happened with you and Ferrell?", and all this kind of stuff. I remember Meryl Streep came up to me, and she was so confused by the reviews. I actually wasn't surprised by it, especially given some of the targets we were hitting. Also, like you said, we weren't showing some layered analysis of how complicated the inaction is because the truth is that it's not complicated; it's ridiculous. So I wasn't surprised by the negative reviews, but I was surprised by the anger and the personal attacks. And then when the movie came out, it was the exact opposite. People in Brazil were rallying around it, Zelensky in Ukraine cited it, and there were people in the streets in France. Netflix was showing us the kind of data on social media responses, and it was overwhelmingly positive.

But what was really scary about it were the exchanges I was having with members of the news media, even the occasional politician and just friends, and I could tell that they didn't really know what was going on. And I kept trying to say, I don't care if you like the movie or not. It's a movie. You're supposed to like it or not like it. I've gotten bad reviews before, but there was this sense—it wasn't like people were saying, "Look, we're in real trouble with this climate thing, and unfortunately, this movie didn't do it for me."Cool, one hundred percent cool. But instead, it was people looking to pound and dunk on tweets, and it kind of scared me. It was like, "Oh, there's a particular crowd that is all about whether they didn't like the film or not." Which, once again, is fine, but I'm not seeing any kind of curiosity. Or,"fine, that movie sucked, but why is he so freaked out?" And it went all the way back to that very first kind of big profile piece I did with this guy from Vanity Fair. And that attitude never wavered through the whole experience, while real people were like, oh yes. So it was really wild, the ups and downs, and then it turned it into like an online fight between climate scientists.

Robinson

Well, that was one group that really did appreciate it. There are a lot of climate scientists who came out and, I'm sure, thanked you personally and said, finally!

McKay

And activists and climate journalists. But there was a jump with the movie, which every movie kind of teaches you something because there's always something that you haven't accounted for. And in this case, it was really the experience of a culture that was gaslighting people. That became the common thread with all these different countries and activists. But then there were really moving responses, like George Monbiot saying that it moved him to tears because for decades, he's been gaslit and marginalized. So it ended up being probably the most incredible experience I've ever had releasing and making a movie, but there was always that little part, even when it was all over, that scared the crap out of me. It was like, well, I didn't like the movie, and I would always say, that's fine, but if I made a movie about contaminated food, and you hated it, that's cool, but what about the contaminated food? And there was just no desire or curiosity there.

And then at one point I said, I read all this data, and I think we're five years away from compound disasters, where there are fires and then immediately there's flooding or multiple hurricanes, and that goes into a realm that scientists or sociologists call doom loops, where you're always reacting to disasters and don’t have time to work on the underlying causes. And oh my god, I posted this on social media, and people responded: you're crazy; what an idiot; he's overreacting. And there was a lot of eye-rolling that just really spooked me. Oh crap, is the news media never going to wake up to this? At that time, I couldn't imagine that we would go this far into it. I could list 50 things since the movie came out that are just jaw-dropping.

Robinson

You mentioned George Monbiot. He was very affected by the movie and then had a real-world Don't Look Up moment. Famously in the movie, when the scientists go on the morning show, the hosts are like, can you put a positive spin on this? Is there some way to make this cheerful? And the scientists are like, no, don't you understand, we're all going to die? And Monbiot, after Don't Look Up came out, went on a British morning show, and he was asked something like, well, don't you think activists are hurting their own cause? He broke into tears on the morning show, going, don't you understand? We shouldn't be having debates about whether the activists are helping or hurting their own cause but about what is actually going to happen to the planet. And then there are headlines in the British tabloids that “climate activist has a cringe meltdown on air.” It was just like the film, unfortunately. The film explains how these institutions work, and in the three years since its release, you can see these institutions working in exactly those ways.

McKay

Yes. I think part of it was that we are, in fact, living in a broken clown show. There's still a lot of pretending that it's still 1996 and the New York Times is still smart and doing challenging journalism. And the people that are on MSNBC and CNN are experts. There's still so much economic incentive to keep that alive. And Alex Steffen, who's a climate futurist, had one of the greatest lines about it in something I read of his where he called it “sunk cost expertise.” It's this post-Cold War expert educated pundit, journalist, media voice. Their framework no longer applies to the world we're in, but their status, paycheck, and community does. [...] The news is just a shell of what it was. And the funny thing is, it's been three years, and I now look back on it, and I don't think I portrayed the news in enough of a crappy light, actually.

Robinson

Yes, they actually let the scientists on the air in the movie.

McKay

Exactly. And the president, who's kind of a mix of Trump—well, her son's Trump, but she has a Clinton / W. Bush kind of vibe. And even she goes with the tech billionaire, and they do some kind of mission to stop the comet, whereas we're not seeing the slightest indication of that in real life.

Robinson

What I've said before is, actually, is that the real world situation is as if in the movie the candidates were competing in their platforms for who could maximize the likelihood that the comet would plow into Earth. That's the reality we live in. In the movie, the president, when it's in her interest, actually takes the problem somewhat seriously. But when I saw Kamala Harris debating Donald Trump, and she was talking about the need to expand fossil fuel use so that America may maintain energy independence, or whatever they call it, I thought, it's like you're competing to see who can get the comet here faster.

McKay

And that was one of the craziest campaigns where, once again, this same kind of crowd was like, we have to pretend everything's great. Shut up and stop criticizing. And I kept saying throughout it, climate breakdown is not an issue [in the campaign]. I would say to people, are you aware that we will be busting through 2 C warming above pre-industrial in the next eight to ten years? That was unthinkable 20 years ago. No one would even have said that out loud. We're now likely going to cross 3 C warming above pre-industrial in the next 20–25 years, and that's an event where you start talking about the possibility of a billion people dying. And now we're looking at within the next 70 years, possibly 4–5 degrees Celsius warming, and that gets into full extinction level events and the host of issues around it: droughts and food supply destabilization that are just never-ending.

So the idea of going through a presidential campaign against the goon Donald Trump, who we know can't even comprehend climate warming, but you're supposedly the sane candidate? You're talking about fracking, and meanwhile, the president you work with won't declare a climate emergency? There's a long list of much less urgent and serious things that we've declared an emergency on.

And then when we pushed Biden out into that debate and he could barely speak, I remember saying, this is far more absurd and cartoonish than Don't Look Up. And once again, that crowd was kind of undressed by that moment. They really showed how they have no credibility.

Robinson

I would literally rather have the Meryl Streep president from the movie. You'd have a better chance of having something be done.

McKay

Right. I would take the Meryl Streep character over Joe Biden as an active president. Would you take Meryl Streep over—clearly over Trump, but over Obama in some ways, maybe?

Robinson

Unfortunately, the fact that mining the comet turned out to be an extremely lucrative proposition that couldn't be turned down kind of derailed the project. But until then, there was this moment in the movie, which is a surprising moment, where they all kind of get behind this equivalent of the Green New Deal solution because it becomes politically opportune.

One of the things that I've always felt that the film captured profoundly in a way that I haven't seen discussed elsewhere is a surprising, counterintuitive thing about human nature. It's in the title of the film, Don't Look Up. After it becomes clear that the effort to destroy the comet is going to fail, and then the scientists start the "just look up" campaign. The counter point by the kind of MAGA people is, "don't look up." Like just don't look at this problem. And one of the interesting things about that is that what ends up happening in the film is that once the comet finally appears in the sky, the level of denial actually accelerates. You might think that the level of denial would decrease once the evidence actually showed up, like once you couldn't deny because it's right there in the sky headed for you. Everyone can see it if they just look up. But the denial actually increases as the problem becomes more evident.

And in the three years since the movie has come out, I have really noticed that dynamic, like as the climate crisis becomes more urgent, somehow the level of denial increases. Instead of the accelerating climate catastrophe causing people who were previously in denial to abandon that denial, it has the opposite effect. And that's a crazy thing, but it's a thing that the film gets, and that is, I think, true about reality too.

McKay

Without a doubt. There are studies that back up what you're saying. Climate coverage has actually gotten worse in the last couple of years, and they're doubling and tripling down. Look, you know the center of what we're dealing with: it's the corporate imperative to get the stock price up no matter what. And it's as crazed and as addictive as someone who's smoking crack or heroin or crystal meth. That probably is the best comparison. And you'll see that in those cases, too, they're tragic. People will suffer from that kind of virulent addiction. And you can have people living in a hole in the ground and thinking their life is great because they're on meth, and they'll fight you harder at that point than any other point to keep that fix coming. That's the center of what we're dealing with.

I've had conversations with people whose economic security and identity depend on them not taking in the enormity of the challenge we're facing. Can you imagine what would happen on MSNBC if they cracked open the box of the reality of climate even ten percent? It kind of washes away everything. You start realizing that the Democrats are just as craven, just in a way that's more pretend. You realize, oh, all of our advertisers are participating in this. Oh, everything that got me here to host this show is now null and void. It must have been like this when Germany invaded Poland, and people were like, hey, Neville, what's going on? Neville Chamberlain instantly became the most irrelevant person in the world. Neville Chamberlain signed that treaty because England was still demoralized, licking its wounds after the brutal World War One. They weren't in any way built to saber rattle. You can imagine the amount of think pieces that were written about how that treaty was a great idea, and in one moment, he was completely irrelevant. The point being that, how could the New York Times—even though they have some great climate writers there—or MSNBC or CNN ever present the reality of the story? They have to pretend. They're built on a petro economy and culture.

Robinson

Well, it's interesting that you bring up that moment before World War Two. One of the things I've read is that when Chamberlain came home having signed the Munich Agreement to let Hitler carve up Czechoslovakia, there was an expectation that he would be met with disdain, and instead he was met with cheering people. There's been a couple of writers who've written about that weird moment in England where everyone in their heart knew that this was not a solution, that this was fake, but they all had an interest in preserving the illusion that allowed them to cheer and celebrate Chamberlain for having made the agreement. They knew that Hitler was an aggressor and that he couldn't actually be contained, but they wanted to believe otherwise. They had to believe otherwise, so they actually celebrated him as a hero when he came home. But there was this note of emptiness or falsity to it, which I think is a fascinating parallel with the current moment, where there is this falseness.

And one of the things that I think caused so many people, so many ordinary viewers, to have such a positive reaction to your movie was that it was an emperor's new clothes kind of thing where the movie really pierces the bubble of denial, and once you've pierced it, it explodes, and you can't maintain it anymore.

McKay

There's one line in the movie—there are a bunch of lines that have been quoted and talked about it. This one hasn't, but for me, it was directly pointed at the centrist, liberal culture and it's the scene where Leonardo DiCaprio’s character, Professor Mindy, is deciding to work within the system, even though it's insane what they're doing. And so there's a scene where DiCaprio is saying, I'm going to work within the system. He's kind of pointing at this small riot that's around him, like, what is this going to do? And Jennifer Lawrence's character and Rob Morgan's character are like, you're crazy—you are picking a lie just for stability. And I think they even mentioned how he's kind of enjoying his celebrity. There's a line where Rob Morgan says, sometimes you gotta just do the right thing.

And that is what I've been saying for 20 years to this constantly capitulating and compromising money liberal clutch that has steered us towards disaster: at what point do you just start putting one foot in front of the other and doing things that need to be done, as opposed to constantly walking sideways to play some abstract political strategy game? And that line, for me, was always a big line. Sometimes you just need to do the right thing. It was crazy.

I remember saying something a couple of weeks ago: is there one reason on God's green, fast-turning brown Earth why the Biden administration is not declaring a climate emergency? And no one can answer it. There's no election. They don't have to worry about that. He doesn't have to worry about that.

Robinson

He’s at his “fuck it” stage. He's pardoning his son. He can do anything. He doesn't care.

McKay

And we know what the real answer is, and it's a very uncomfortable, dark answer. Have you seen any mainstream news media ask the question, "why isn't he declaring a climate emergency?" And I haven't even seen it posted. I haven't seen anyone ask it, and it's one of the craziest things I have ever seen. It's just amazing, how thick the amount of pretend is. It goes on, obviously, with the ethnic cleansing in Gaza. It goes on with the inequality, poverty, the towering corruption in our political system. There are so many levels of pretend, but still, the king is climate because we've let it get to the point where it now really reasonably could be an extinction level event.

Robinson

It’s like that movie, The Zone of Interest, about how people try and live a fake kind of normal life in the full knowledge, with this level of denial, of the atrocity that's incredibly obvious. If it's in everybody's interest to maintain a denial, we can maintain denial. And one of the useful things about Don't Look Up is that you show how, essentially, when people's interests coincide, it can lead them to do insane things. So when it turns out that dealing with the comet would require the sacrifice of an awful lot of corporate profit, all of a sudden, a lot of people start having faith in the scheme by the billionaire, played by Mark Rylance, that he's going to explode the comet and mine it for precious rare earth minerals, even though it's untested. We know it's untested, and it probably won't work. It is wishful thinking borne of self-interest.

And so, even though it seems like maybe the billionaire doesn't know what he's talking about, maybe he does. And considering the upside if he does, we have that kind of faith. I don't think many of the critics noticed the kind of parallel with geoengineering: let's believe in the magic solution because the magic solution might mean that we don't have to confront these things directly.

McKay

It's really remarkable. I think the story of our time, if you want to frame it as the collapse of the West, is how easily incentives, self-interest, moral hazard, and convenient worldviews can warp us into making some of the strangest decisions imaginable. And obviously, there's a lot of military grade marketing, advertising, misinformation, and propaganda that's pushing a lot of this. But still, it's remarkable how easily we can just be pushed so we're looking at something that isn't the very real hardcore scientific reality of climate breakdown: people actively dying, cities being wiped out. The reality of weaponized, militaristic, run them up: Netanyahu and the Israeli government. Or people just suffering through lack of health care. Guns, the opioid epidemic, and now sports betting. So all these realities, and the very clear reality when it comes to our politics.

I said it on The Big Short tour when we won the Academy Award. I said, just don't vote for clients. Don't vote for candidates who take money from big banks and billionaires. And it was so funny after I said that. There was immediately a bunch of people saying, he was attacking Hillary Clinton. And I was like, I didn't even say her name. But, yes, it's wild.

I was very naive. I just never thought we'd let it go this far. There were several moments in the last couple of years where I thought, okay, we're going to declare a climate emergency. We're going to at least put some federal funding into aqueducts, bolstering the power grid. We're going to call the oil companies in. I thought we’d start, but there just hasn’t been anything. It's not even part of what people are thinking about.

Robinson

Well, as you say, one of the reasons you pissed off critics is because the criticism of the media in the film is pretty strong. And you and I have talked before about how there needs to be a real front page, one organized as if ordinary moral priorities were actually applied to how you prioritize the news. Because when you start critically examining a paper like the New York Times, it's true that on a very superficial level, it looks like a newspaper and there's some news in it, but when you start flicking through it, you notice that on page A12, there's always some story that says, "and scientists warn that the collapse of the ice shelf is even closer than we thought before," and then all the warnings are them screaming, as the scientists do in the film, as much as they can in print. This is buried in the back of the paper, and the New York Times has still refused to even stop carrying fossil fuel ads. They still won't make that pledge.

McKay

They're even worse than that. They did a whole greenwashing podcast, I think it was for Chevron. They're utterly craven. At one point in the last year, I started saying, it's dangerous to read the New York Times. I've had several conversations with people who consider themselves well-informed because they read the Times, or they listen to that Daily podcast, and who were traveling to places that were in the midst of a climate disaster. I had one family member who, a couple of years ago, was going to Japan, and I said, they're in the midst of a really nasty heat wave [note: over 15,000 people were hospitalized due to the 2022 Japan heat wave], and there's a typhoon headed to Japan, and the family member said, what are you talking about? No, there's not. And I'm like, look, just do me a favor, and please look it up.

And the unsaid part of it was that they read the New York Times, and it was barely mentioning it. Sure enough, the family member goes to Japan. The typhoon hits, and they're stuck in their hotel room for two days. Now, they were okay. But then I have the same thing with a family member going to Greece during those fires. Every exchange, I say, are you aware of the big fires that are going on in Greece? And every change is the same. You can tell they're like, oh, Adam's extreme about the climate. And I'm like, whatever, but please look up these fires that are going on. That's really the experience.

Not only is the collapse of our news media actively putting people in danger, but for those of us who for years have been trying to advocate and inform, it's made us look crazier and more extreme. We just cite actual events. We post videos of the event happening. We post Berkeley or Earth Systems data. And yet, still, these brands still hold that old respect from years ago, and it's really actively dangerous. The craziest was that we didn't even hide it. Really, the "Daily Rip" in Don't Look Up is "Morning Joe," and in the middle of Biden’s fairly disastrous term, I heard that he loves "Morning Joe" and was watching it every day. And I just thought, oh no.

Robinson

Yes. As I said, one of the things that unfortunately has to make you kind of pessimistic is that you might think that, when climate change was still in the future, people couldn't see the consequences, and the denial was possible to maintain. But now, as these things accelerate, surely we'll have to confront it because it'll be right in front of our eyes.

Turns out that's not true. What if in the movie you had a paper like the Times that just treated it as if the comet wasn't coming? Or you went to page B12, and it said, by the way, comet still on the way, going to destroy all life on Earth in 60 days? That's the world we live in. It's so bizarre and perverse and monstrous to have that because it does make you want to scream. All the reviews of the movie were like, "Adam McKay is screaming at people." It's like, what do you do?

McKay

That's the million dollar, or the eight billion people, question with climate. All these climate comms people like to say how you're supposed to talk about it, but really, the only thing that's been shown to sway people is disruptive protest and emotion. The one thing the neoliberal economic order cannot stand up against is emotion. But it's clear at this point the New York Times and mainstream news—the Washington Post people barely even talk about anymore, it's falling apart so much—seem very committed to reporting World War Two as a series of one-off incidents where angry boaters on Normandy beach confronted armed German tourists, and it seems like their plan is just to report each disaster as a disaster and never tie it together.

Robinson

Oftentimes, you'll read a story about a wildfire or a massive drought, and the context of it, or why is this happening—climate change—isn’t even in the story.

McKay

Over the last 40 years, the markets, financialization, and industry kind of took over our culture. These institutions started promoting the people who asked the fewest questions. They started promoting the people who were focused on their own career. I've argued with people about this before: I think career is the ugliest word there is because it's just like you and your story removed from the collective good. And I've always thought the real villain at the center of The Wire was careerism and a sort of tunnel vision. And so, yes, we're really in a place where the people in charge of these institutions, the people walking the depths, so to speak, of these institutions, have been promoted precisely because they're incapable of asking big questions, challenging policy, challenging their boss, and looking at their own incentives in a critical, self-aware way.

Robinson

Well, as we come to the conclusion here, we've given a quite bleak picture of American political and media institutions so far. And I think some people find you depressing to listen to. But actually, one of the things that I don't think comes as a surprise and that I've not mentioned about Don't Look Up, and that I said in my review of the movie, is that I thought one of the things that the critics missed when they said it was a work of anger or nihilism or rage is that, actually, it's “a film with great faith in humanity and cynicism only about the institutions we've built and the particular people who hold power.”

And I think that faith in humanity, as opposed to people in power, is born out a little bit by the reactions to the movie. We have these institutions that we've discussed, but most of us aren't in those institutions. And in the movie, there are a lot of good people who care and try to do their best to avert this. And I think that that's one element that, I thought, was missed in the reviews. Obviously, in the movie, it all ends in catastrophe, but the love of humanity is there. It isn't Idiocracy. It isn't like, look at all these morons. That's not the message you have or the worldview you have.

McKay

No. And one of the more cynical things that I've seen is this idea that when people are very alarmed or pointing out the naked empirical truths that we're all dealing with, we should call them "doomer" or doom and gloom. I'm convinced at some point in the next three or four years, there's going to be a memo leaked that fossil fuel companies created that talking point of “doomer” and that it was from some troll accounts. They spread it because it is the ultimate dream of the oil companies that anyone really trying to raise the alarm has the Bernie Bro thing, where the only candidate in my entire life who hasn't been bought and paid for is labeled as this not cool thing.

So the truth is, and I've said this many times, the only reason I'm talking or writing stuff about it, or posting or whatever, is because there are things we can do. The list of options has narrowed quite a bit through decades of inaction. But science is an incredible thing when it's funded and focused. We don't even know because we haven't even tried to really create research facilities around the world with $500 billion of funding to work on carbon removal, to work on ways that the Earth's energy imbalance is interacting with the chemicals that we're already polluting with. There are so many ways to bolster existing carbon sinks to protect a couple of the major earth systems that are already showing major signs of collapse, like the Amazon rainforest. There are just so many things we could be doing, not to mention energy transition, oil companies stepping down—at some point they're going to have to be nationalized. Anyone saying anything else is lying, and we will have to have a rapid drawdown of fossil fuels.

So there are so many things that we are very capable of doing, and there are a bunch of things which maybe we could do but we still have to try. So, everyone uses the World War Two analogy, the rapid mobilization where almost the entire planet's focus and efforts changed. Now in that case, unfortunately, it was dropping bombs and machine-gunning people. But the point was that there was a rallying that has rarely been seen in the history of mankind. And we are well past the point of that moment, but it can still happen.

Robinson

Well, one of the things that the film succeeded in doing was to shake people awake a bit, and I think people responded to that really well, partially because I don't think it's bleak. I don't think it's hopeless. It's funny. You managed to reach people, and you managed to somehow entertain people and educate people at the same time, which is a pretty rare achievement. I would encourage people to go back and revisit it, to rewatch it, and read the article that I wrote about some of the themes that people missed, and then to not think about this as a heavy-handed satire, but to discuss the points that are raised, namely, the crisis that we face and the obstacles that we face coming together to solve it. That's, to me, the central takeaway from the film. I don't know if you would agree with that.

McKay

Yes, for sure. We are in the midst of a ridiculous clown show, but the stakes are very real. And it's a movie, not a mass movement. It's not like a billionaire seizing the levers of media. But it's cool that now, when people see the news being ridiculous about climate, they call it a Don't Look Up moment.

Robinson

Yes. It slipped into the vernacular.

McKay

If you had told me before the movie was released that that would be the one result, I would have been totally happy. But we've seen that it has become a rallying cry for certain activists. A lot of people I engage with were really moved by it and had very profound experiences. And then some people didn’t, but that's fine, too. At the end of the day, it's hard to totally know, and Netflix won't really say it, but the most conservative estimate is that 400 million people saw it, and it's possible it reached half a billion. There's no platform like Netflix for worldwide eyes on something. So it was one of those great experiences where we had the window, we had the financing, we had the actors, and we took the biggest swing possible. It was really cool seeing hundreds of millions of people be like, yep, that's what we're experiencing.

Robinson

Well, now you've just got to do something like that every year. You make it, and then get into the same pattern, and we backslide. And then you got to shake people awake. Again.

McKay

True. We need dozens of filmmakers. This needs to be a big effort because it's too easy to isolate and criticize me. But if twenty other filmmakers were doing it, it could really start to have some power.

Transcript edited by Patrick Farnsworth.