Why Do We Love Some Animals But Not Others?

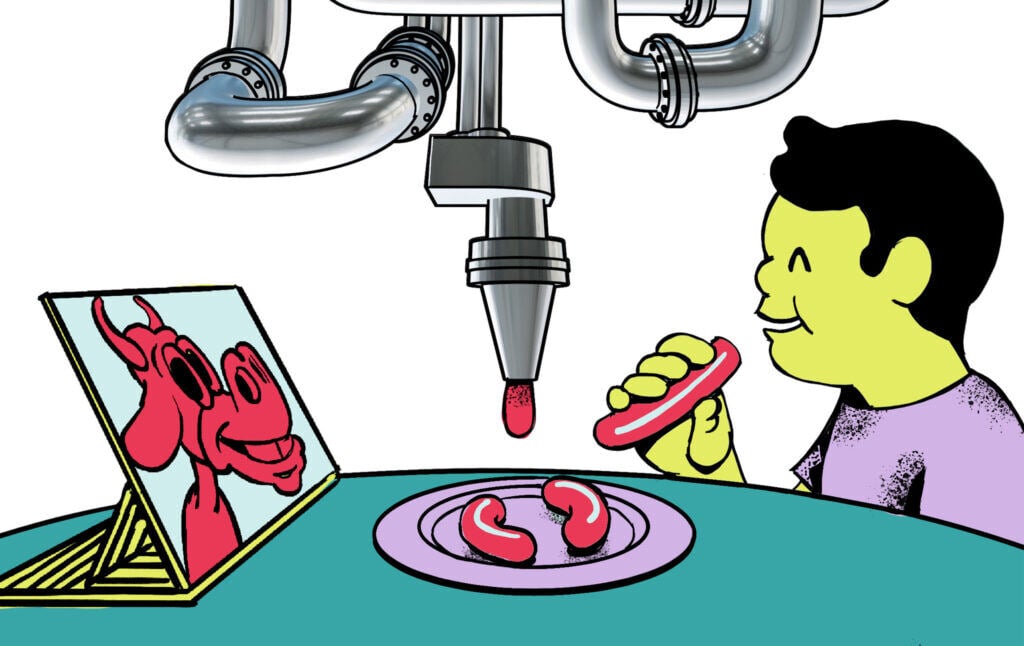

Our culture is filled with images of adorable animals, even as we brutalize them by the billions.

Everyone loves animals! At least if they are in two dimensions. Children’s picture books are full of mice and frogs and rabbits and monkeys. Kids watch Peppa Pig and Daniel Tiger and Bluey. They wear Hello Kitty backpacks and have dinosaur stickers. When you grow up, you are somewhat less surrounded by images of animals, and most of us no longer cover our binders in animal stickers. (I still do.) But even as our backpacks become much more boring, we still love animals. We love a video of an adorable sloth, or a cat attacking a Christmas tree, or a beluga whale appearing to enjoy a mariachi band. We love our pets and often describe them as “family.”

But we have not constructed a society that treats animals very well. In 2019, the U.N. released a 1,500-page report called the “Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services.” As the New York Times noted, the report found that human “activities like farming, logging, poaching, fishing and mining are altering the natural world at a rate ‘unprecedented in human history.’” Human-caused climate change and the development of roads and cities have also altered or destroyed the habitats of species. As a result, an astonishing one million species may be on the verge of extinction thanks largely to human activity. Since 1970, across North America, bird populations have declined by 3 billion. Animal populations worldwide have declined by an average of 70 percent, and in many places, most of the animals that once existed are simply gone, in a devastating phenomenon that has been called the “sixth mass extinction.” The changes are shockingly rapid, since they have occurred not over millions of years but in the course of a single human lifetime.

Then, of course, there’s factory farming. Hundreds of millions of animals are killed every day for food and usually kept in appalling conditions. They suffer virtually nonstop from their births to their premature deaths. They live out their short lives in cages so small that they cannot move. Their dwellings are filthy. They are isolated from other individuals, tend to get sick, and rarely get fresh air before their deaths. This is a system where sentient beings experience torture on an unimaginable scale.

I am constantly struck by the disjunction between the images of happy little animals in children’s picture books and cartoons and CGI films and the bleak reality of life for pigs and cows in the real world. It makes the children’s books feel kind of dark and disturbing to me. Nobody wants to be a killjoy, and even the most moralistic leftist (and I’m just about that myself) may hesitate to spoil the fun of a toddler reading Don’t Let the Pigeon Drive the Bus by pointing out that, in fact, the majority of birds in a lot of places are gone thanks to our wanton destruction of the natural world. But sometime we’ve got to confront the sheer weirdness of the contrast between our celebration of animals in images and what we actually do to them.

Other than pets, many of us don’t encounter animals much in our day-to-day lives. Developers purge new neighborhoods of all wildlife, making places where almost nothing non-human can live other than the carefully maintained grass and a decorative tree here and there. Nature is shamelessly bulldozed and paved over, and conservatives have (ironically) long viewed many conservation efforts as a particularly annoying form of government meddling. One of their classic tales of bureaucracy gone mad is when a shopping mall or hotel is held up because some endangered species of owl has been found in a tree on the property. Rush Limbaugh was frank about how he thought such situations should be dealt with:

If a spotted owl can’t adapt, does the earth really need that particular species so much that hardship to human beings is worth enduring in the process of saving it? Thousands of species that roamed the earth are now extinct… There’s no reason to put the timber business out of commission just because of 2,200 pairs of one kind of owl [at the expense of] 30,000 jobs. That’s the wrong set of priorities.

While it’s rare to hear it put so explicitly, a kind of savage Darwinism runs through right-wing ideology generally, the idea that strength is virtue and the weak deserve their fates. Still, Limbaugh almost deserved a certain amount of credit for his absence of hypocrisy. He didn’t pretend to think animals were worth trying to save. If job creation necessitated mass killing, well, so much the worse for other species. That’s life.

Personally, however, I can never shake the conviction that there is something deeply and terribly wrong about the mass killing of other species. Carol J. Adams, in the feminist-vegetarian classic The Sexual Politics of Meat, describes a common experience that turns people against meat-eating: the realization that there is a logical disconnect between the attitude we have toward some animals and the attitude we have toward others:

At the end of my first year of Yale Divinity School, I returned home to Forestville, New York, the small town where I had grown up. As I was unpacking I heard a furious knocking at the door. An agitated neighbor greeted me as I opened the door. “Someone has just shot your horse!” he exclaimed. Thus began my political and spiritual journey toward a feminist-vegetarian critical theory. It did not require that I travel outside this small village of my childhood—though I have; it involved running up to the back pasture behind our barn, and encountering the dead body of a pony I had loved. Those barefoot steps through the thorns and manure of an old apple orchard took me face to face with death. That evening, still distraught about my pony’s death, I bit into a hamburger and stopped in midbite. I was thinking about one dead animal yet eating another dead animal. What was the difference between this dead cow and the dead pony whom I would be burying the next day? I could summon no ethical defense for a favoritism that would exclude the cow from my concern because I had not known her. I now saw meat differently.

The love and care shown for pets seems almost boundless—at least for the pets that are wanted. But the mass breeding of pets is a cruelty, too. And the overpopulation of cats and dogs—and a spike in euthanasia rates in 2023—is a major problem in U.S. cities. Many pets were also no longer wanted (or people just can’t afford them anymore) after the height of the pandemic, when pet ownership soared. Still, it’s very hard to reconcile our “love” of pets with an outright indifference to or acceptance of factory farming. As Marina Bolotnikova, who has written about animal rights for this magazine, puts it:

Factory farming has literally remade life on Earth. It has replaced wild animals with billions of farmed animals, both victims of and unwitting contributors to our planetary crisis, that live and die in conditions of bottomless cruelty. Factory farming is also polluting communities’ air and water and spewing greenhouse gasses into the atmosphere, making up 15 to 20 percent of global emissions. More than a third of the planet’s habitable land is devoted to animal agriculture, land that could otherwise host wild ecosystems that sequester carbon emissions.

We keep this system far out of sight and out of mind. Efforts to expose it are ruthlessly prosecuted. Any effort to free the victims, or even to enter and document the treatment, requires violating private property rights, meaning that activists can only succeed in collecting evidence if they are willing to break the law and risk criminal punishment (often under special “ag gag” laws). Bolotnikova has written about the importance of such “direct action” as a way to bring public attention to the cruel treatment of animals.

Bolotnikova notes that for many, “confronting the violence behind something so intimate as the food we eat makes them want to shut down rather than take action.” But, she argues, we must confront the truth, and it can be liberating when we do. Is it really possible to live indefinitely in denial, looking at cheery images of cartoon animals, while endeavoring constantly to suppress recognition of the horror on which our food system is built? Even if it were possible, would any person of conscience wish to live in this state of moral dissonance? Far too many injustices persist because it’s too easy to mentally wall them off and act as if they are not happening.

The way we treat non-human creatures on this planet is often appalling. It’s also destroying our own species’ chance at a healthy future on Earth. Every creature on the planet should be seen as special and worthy of life. Instead of loving some creatures, we’ve got to love them all. This means radically rethinking our treatment of animals—and the food we eat every day.