The Voyager Probes Were a Triumph of Collective Endeavor

Today, wealthy capitalists want to strip-mine the wonders of outer space for their own greed and vanity. Voyager offers another way.

In late 2023 the signal from the Voyager 1 space probe, now far outside the solar system, suddenly became meaningless. News outlets around the world took notice. From the BBC: “NASA’s Voyager 1 Spacecraft Sending Gobbledygook Data Back to Earth.” In the New York Times: “Voyager 1, First Craft in Interstellar Space, May Have Gone Dark.” From the Indian Express of Mumbai: “Voyager 1 Goes ‘Senile.’”

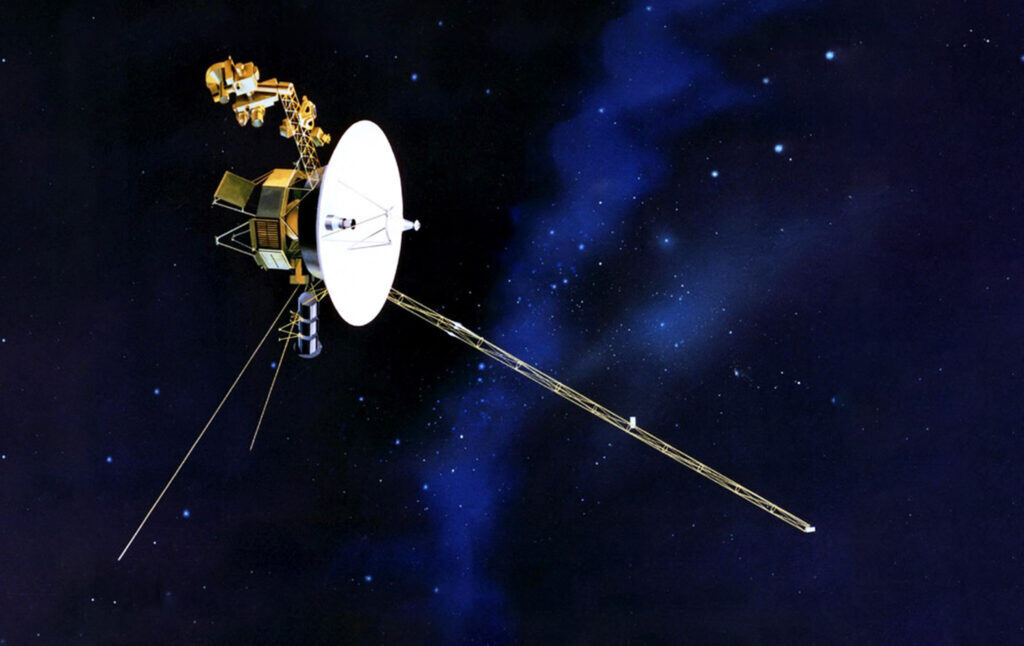

Why does a probe that launched when The Bionic Woman was big on TV still rate this level of concern? Voyager 1 last explored a planet in 1980. Its cameras have been kaput since 1990. The only data it has returned since then—particle counts, cosmic ray readings, magnetic field measurements—aren’t the sort that turn the public on. The spacecraft’s great feat these days is to fall through nothing toward nowhere at 14 times the speed of a rifle bullet. In a few more years its power source will die, and that will be that.

Yet millions of us still care a lot about this ungainly, obsolete machine. The twin Voyagers’ mission manager, Suzanne Dodd, calls them “humanity’s spacecraft,” and with good reason; if there was ever a people’s space shot, they’re it. Like our national parks and public libraries, they are a triumph of nonprofit collective endeavor. Their mission is not to claim, extract, or exploit resources or to humiliate rival superpowers, but to deliver a public good.

And unlike human space “explorers,” who can only set foot on ground that has already been surveyed at high resolution, the Voyager probes truly have revealed unknown worlds. Jupiter’s moon Io, pimpled with volcanoes spewing hundred-mile-high umbrellas of sulfur. Europa, hoarding more liquid water than Earth under a smooth shell like a cracked egg. Saturn, capped by a hexagonal storm bigger than Earth but neat as a honeycomb cell, and its finely-grooved ring system, wide enough to bridge the gap from Earth to the Moon but only about 30 feet thick. Saturn’s mega-moon Titan, with rains, rivers, and seas of ultracold natural gas under a dim ocher sky. All told, Voyager revealed 20 planets and major moons in detail for the first time. Until then we had no idea what a mad zoo of landscapes is rolling around over our heads—cryogenic dust geysers, red lava running under a sky spanned by Jupiter’s paisley glory, a whole world covered with snow. All pure, all wild.

These spacecraft—antique engines of wonder, still ticking 47 years after launch—are a glimpse of blue sky above the prison yard of high-tech capitalism. They suggest a relationship to technology different from today’s treadmill of ruthless manufacture, rapid obsolescence, barbarous disposal, and dubious net benefit. (For all their technological toys, surveys suggest Americans are no happier today than in 1946). Today, the average phone packs more computing power than a thousand Voyagers, but is assembled in a dystopian hive-factory by an army of disposable workers. It’s carbon-intensive to produce, the cloud resources behind its apps spew more CO2 every time we tap up a cool service, and it serves only 2.5 years before exploring the inside of a landfill. Over 5 billion phones, with all their gold, tantalum, tungsten, cobalt, and lithium, much of it destructively or illegally extracted, are thrown away each year.

A probe like Voyager 1 has a delightfully different product life cycle. In old videos, skilled workers wearing white “bunny suits” watch intently as one assembly is lowered onto another in the Jet Propulsion Laboratory’s clean room. Every operation is handled with a quality of attention most of us would reserve for signing a mortgage. These people make no rote, assembly-line motions; they love what they are making and will work unpaid overtime to make it right. For example, to assure that Voyager’s sun sensor would be sensitive enough to function in the darkness beyond Saturn (not part of the mission’s official scope), engineers designed an extra amplifier into the system without telling management.1 They also placed 4,800 of their own and family members’ signatures beneath each Voyager’s hand-sewn protective blankets, an act reminiscent of the medieval stonemasons who tucked self-portraits into odd corners of cathedral roofwork.2

A Voyager is indeed less like an iPhone than like a cathedral—a durable triumph of supreme skill. And while it’s true that fewer Voyagers get built than iPhones, and cost more, a world in which all electronics were made by well-paid workers, built to last, and recycled with deep care is not beyond imagining.

In Wall Street terms, the Voyagers are useless. Once built, they were not sold but tossed overboard, and their only product, knowledge, is given to the whole world for free, friend and foe alike. They attest that we are capable of high and generous emprise; they scribble a bit of our divinity on the cosmic wall. They are interstellar, history-outlasting, physical proof that, though fleeting and troubled, we can contemplate the universe as a thing to know and admire for its own sake—an artwork.

Lately we’ve heard a lot about a very different space ethos. Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, Robert Zubrin, and others are advocating space colonization with fresh urgency, increasingly impressive rockets, and old arguments. Humans must realize our “destiny in space,” they say. A new frontier will rejuvenate our senile culture. A colony will insure against human extinction by asteroid strike, artificial intelligence, or some other means.

These people have no intention of contemplating anything. The Moon is to be strip-mined for helium-3, the asteroids mined, Mars terraformed. Elon Musk wants to bomb Mars with nuclear weapons to release its frozen subsurface water. To refrain from these enterprises out of a tender regard for nonliving, nonhuman Nature would be worse than woke—the salvation of the human race is at stake. Zubrin bats aside planet-hugging sensitivities with contempt, saying that “Rocks don’t have rights.”

Whether nature has legal rights is debated, actually, but most of us would agree that whether or not rocks have rights, no person has a right to do anything they like with just any rock. At least some rocks, even our society has agreed, have a beauty or integrity that should be respected. If Zubrin dynamited Arches National Park to make riprap, he might find himself weighing this nicety in jail. A sea-smoothed cobble, a natural arch, a barren alp, the most sparsely inhabited desert—none are automatically fair game for any entrepreneur driving a rock crusher. And if a cobble, arch, or mountain can have value, why not—how not—a whole world? What is the inherent worth of Mars as-is? The Moon? The miniature solar systems of Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune?

Perhaps nonzero. Perhaps very great. Perhaps so great that the right thing to do would be to declare them a solar wilderness area, barred forever to the bulldozers. But what about that species life insurance? If we can build a backup planet, isn’t it a good idea, or even obligatory, to do so?

The question assumes that colony-building is a real choice, but futurism has reneged on many promises. Where are the nuclear-powered cars, underground garden cities, electricity too cheap to meter? Interplanetary colony-building is in this class of grandiose impracticalities, a pipe dream doomed by inconvenient engineering truths. We needn’t weigh our obligation to buy species-wide life insurance because it isn’t an option and never will be, this side of the unguessably distant future.

Crewed outposts—stations that persist for as long as they are resupplied and there are no catastrophic system failures—are of course feasible. The International Space Station is an outpost, and outposts on the Moon or Mars could also be built, albeit at extreme cost and paltry per-dollar scientific payoff compared to robotic explorers like Voyager (47 years of nonstop science for roughly 1/65th the cost of the Apollo moon landings). But outposts don’t provide loss-of-Earth insurance; that requires an absolutely self-sufficient colony, capable of housing thousands or millions. And we cannot plausibly build such a colony, now or at any imaginable future time. Not quickly, not slowly, not at any cost.

Off Earth, people can exist only inside failsafe bubbles of high technology. Such systems comprise millions of advanced materials and components: microprocessors, coatings, filters, alloys, glasses, ceramics, plastics, solvents, coolants, lubricants, batteries, motors, gaskets, and much, much more. To maintain such bubbles requires not just these things, but the things needed to make the things, and the things needed to make the things needed to make the things. It requires the whole high-tech economy of Earth, from the extraction of raw materials to multibillion-dollar chip fabrication plants.

To create a society that could carry on if Earth were creamed by an asteroid, we would have to build a working copy of this unthinkably vast, labyrinthine web of interdependencies—something like the combined economies of China, Europe, and the US—in the sky. Plus, given Murphy’s Law, this copy would have to be made redundantly robust against simultaneous disasters—breakages, sabotage, pandemic, meteor strike, political instability, the unforeseen. Otherwise, terminal failure would be inevitable. A space colony would be doomed by the first essential it couldn’t replace.

And that’s just the technology. A species lifeboat would also have to assure food, air, health, indirect supports such as universities to produce future generations of scientists and engineers, and so on—the whole fabric of a sustainable society, with zero outside help, forever.

This mega-scale miracle, if we’re to believe the colonizers, is within the power of a civilization that can’t stop Venusizing Earth, conserve soils, build a nuclear power plant on time or on budget, or convince 29 percent of Americans under 50 that the Apollo landings were real. Can it be proved impossible? Of course not. But is it plausible? No. We are no closer to building a self-sufficient space colony than to controlling the weather, abolishing all disease, or living forever. It would be comparatively easy to transform today’s Earth into a detoxified, climate-stabilized Eden—a project the colonizers don’t seem interested in.

On the contrary, their space hobby will make Earth sicker. The present rate of pollution from spaceflight is small compared to that from commercial aviation, but enthusiasts propose a manyfold growth in launches for tourism, mining, commercial satellites, outposts, and colony-building. This will multiply the Earth-circling space junk that already threatens astronomy, the usefulness of near-Earth orbit, and night’s ancient darkness. Rocket launches also dump hundreds of tons of CO2 and other pollutants into the atmosphere at sensitive high altitudes, injuring the ozone layer and causing other harms. At a time when we desperately need to heal our atmosphere, the space capitalists want to crucify it with a nail gun. The real question isn’t whether colonizing space is feasible—it isn’t—but how much damage is about to be done by people who believe or pretend that it is, and by other would-be sky exploiters.

Finally, it’s worth noting that despite the colonizers’ libertarian rhetoric, social conditions in a Mars colony would make life aboard the HMS Bounty look like spring break in Fort Lauderdale. Packed into a high-tech ant farm and threatened continuously by a near-vacuum on the other side of the wall, every thought, word, and act would be tightly, permanently constrained. You would be about as free to let your freak flag fly as you are aboard a jumbo jet with the “Fasten Seat Belts” sign turned on.

The colonizers’ visions aren’t ennobling and salvific; they’re silly, selfish, dangerous, and authoritarian to the bone. Voyager and the other knowledge-seekers—Viking, Venera, Galileo, Cassini, New Horizons, Tianwen-1, Europa Clipper, and all their kin—exemplify another way.

“We can never have enough of Nature,” Thoreau wrote. “We must be refreshed by the sight of inexhaustible vigor, vast and Titanic features… We need to witness our own limits transgressed.” The Voyager probes gave us all that in spades. They showed us a cosmic wilderness, alien yet familial, condensed from the same cloud of nova-transmuted dust that spontaneously generated our own flesh. And they continue to give. The 24-story dishes of the Deep Space Network still swivel every day to hear their whispered news. They’ve outlasted the Grateful Dead. As of this writing, Voyager 1’s gray-haired managers have coaxed it out of the 5-month coma it entered in late 2023 and are receiving intelligible data again. The probes will run out of power and go dark eventually, but not yet.

The Voyagers achieve spiritual escape velocity from the world of practicality, ownership, profit, and power, bearing proof of better motives into the beyond. They exemplify our ability to love the universe as an artwork, not a dead resource to be processed into profit and garbage. They don’t fly so that the rich can profit or so that we can “learn how to live in space” (which we’re already doing) or because we will ever have any practical use for what they discover, but because humans do not live by bread alone. “Give us bread but give us roses,” the Socialists say, and so we brandish a rose. Voyager sends us roses. Let’s order some more.

- Voyager engineer John Casani tells the story of this “minor engineering conspiracy” at 15:50 of the documentary JPL and the Space Age: The Stuff of Dreams. ↩

- Christopher Riley, Richard Corfield, and Philip Dolling, NASA Voyager 1 & 2 Owners’ Workshop Manual, Haynes Publishing, 2015. Info on signatures, sidebar page 38. ↩