How to Neutralize the Electoral College

The institution is unjust, anti-democratic, and just plain silly. Fortunately, there’s a solution.

This article was expanded from an item in the Current Affairs B›iweekly News Briefing. Subscribe today!

In Maine, two extremely important votes took place this month with virtually no media fanfare. In the first, the state’s House of Representatives voted 74 to 67 to join something called the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact. In the second, its Senate approved exactly the same move on March 13, this time by a vote of 22 to 13. But what is the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact, you might ask? Well, it’s a lot more exciting than its rather bland name would suggest. In essence, it’s a coalition of state governments trying to end the undemocratic power of the Electoral College once and for all.

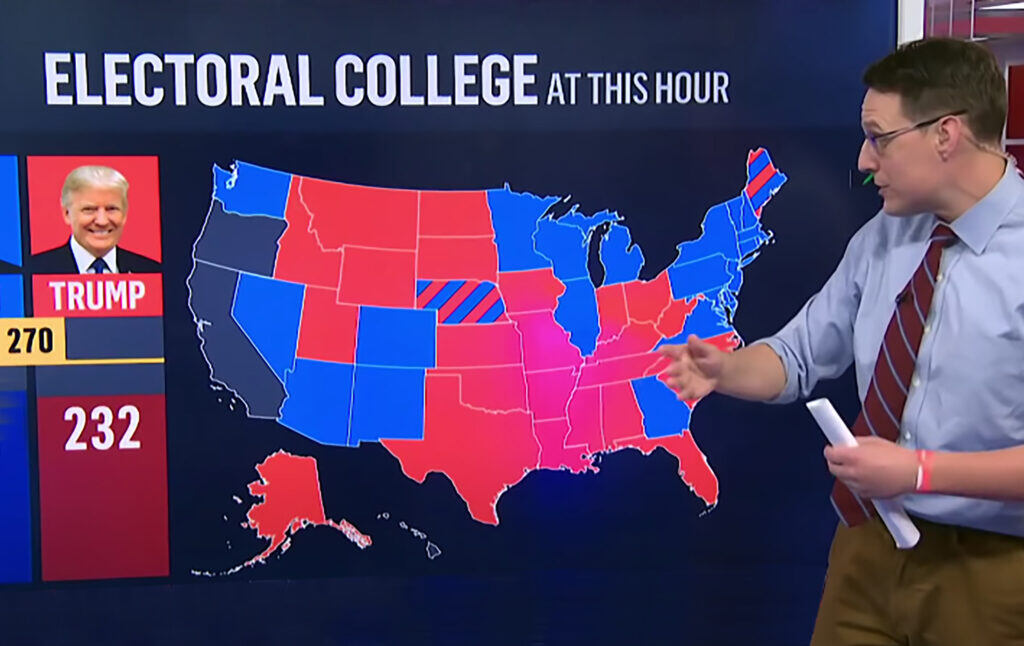

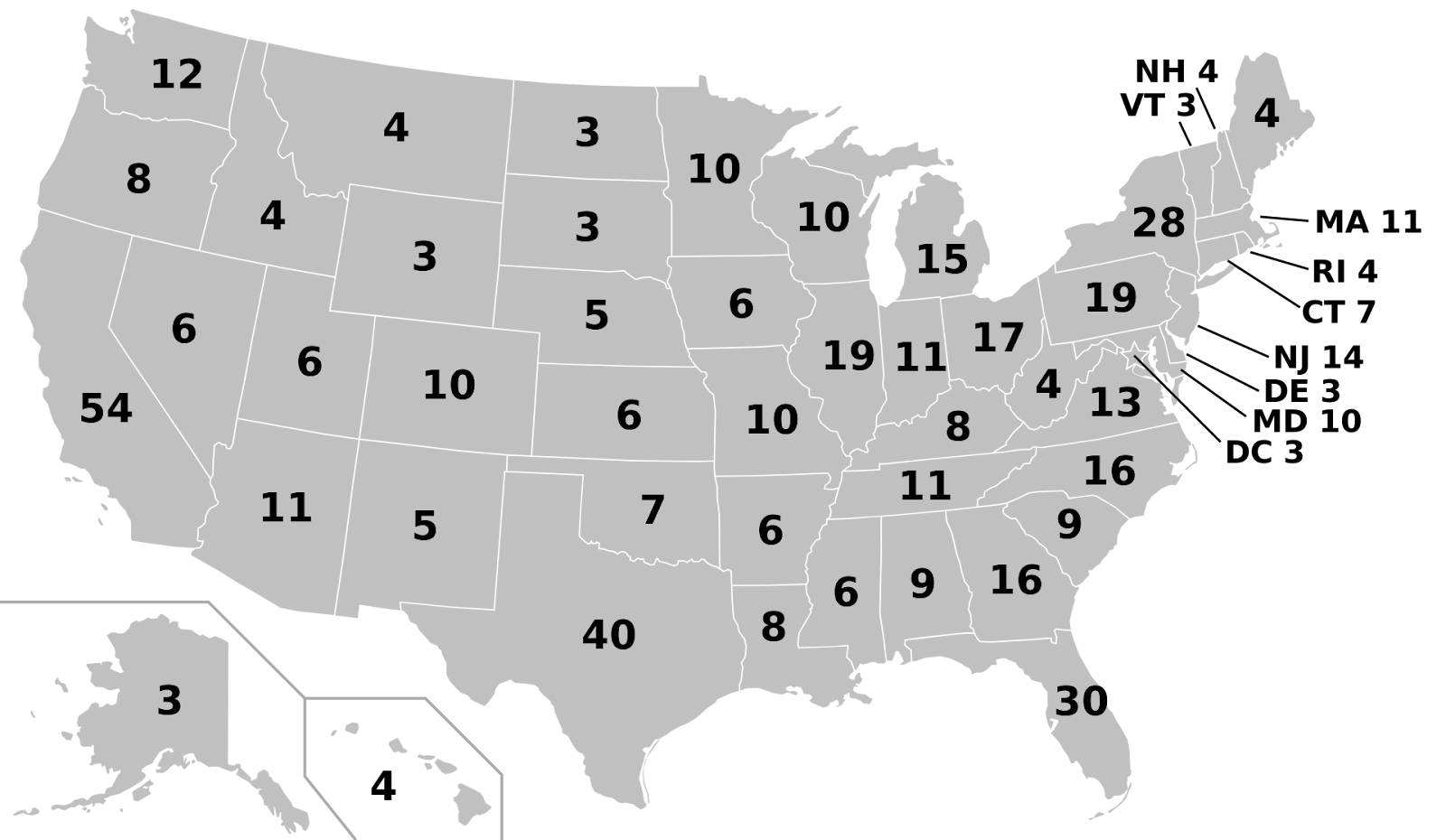

A little background may be in order. As you might or mightn’t remember from your high school Civics class, the Electoral College is an important part of the United States’ democracy—or rather, the shambling fraud that calls itself a democracy. In the simplest terms, it’s a group of 538 people (the “electors”) who meet after a presidential election and cast ballots based on how their states voted. When mere mortals like you and me vote, we’re not actually voting for the president, not directly. Rather, we’re voting for a “slate” of electors to represent our state and cast the real votes in the Electoral College later on. To win, a presidential candidate has to accrue at least 270 of the 538 electoral votes. Each state gets a number of electors equal to the total number of Senators and Representatives it has (plus 3 for Washington, D.C.), and the current map looks like this:

Like a lot of things in the United States, the Electoral College is incredibly stupid. For one thing, it’s vulnerable to being gamed and manipulated in all kinds of absurd ways. There’s nothing forcing electors to actually vote the way their states do, so there’s always the threat of “faithless electors” who go rogue and cast their ballots however they want. (So far this has been a rare occurrence, but as the political climate keeps getting weirder it may not stay that way.) There was also the Trump campaign’s bizarre “fake electors” scam from 2020, in which ten Republicans posed as the electors for Wisconsin and tried to vote for Trump in the Electoral College even though Joe Biden had won the state. As long as there’s an Electoral College, you can never entirely rule out shenanigans like these.

That’s not the worst of it, though. Even when everything functions exactly as it’s meant to, the Electoral College is still unfair and anti-democratic. One major problem is the “winner-take-all” system. Virtually every state—48 of the 50—uses a “winner-take-all” vote, in which all of the state’s electors go to the winner of that state’s presidential election. (Maine and Nebraska are the two exceptions.) That might seem fair at first glance, but in practice it’s not. For example, if 51 percent of a state’s citizens vote for Candidate A, the result would be that Candidate A gets all the state’s electors, and the 49 percent of people who voted for Candidate B aren’t represented at all in the Electoral College. (Remember “no taxation without representation?” That was a lie.) Because of this, presidential campaigns overwhelmingly focus on “swing” states and ignore states where they’re unlikely to gain any electors. According to one analysis, an astonishing 94 percent of the campaign events in the 2016 race between Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton were held in just 12 “battleground” states, while voters in states like Oregon and West Virginia never got a visit from either candidate. And it’s well-documented that niche interest groups within swing states—like right-wing Cuban Americans living in Florida, or Arab Americans living in Michigan—play an outsized role in deciding elections. Meanwhile the entire populations of deep-red or deep-blue states might as well not exist from the campaigns’ perspective. Unless you live in a swing state, it’s unlikely that your concerns and wishes will be listened to.

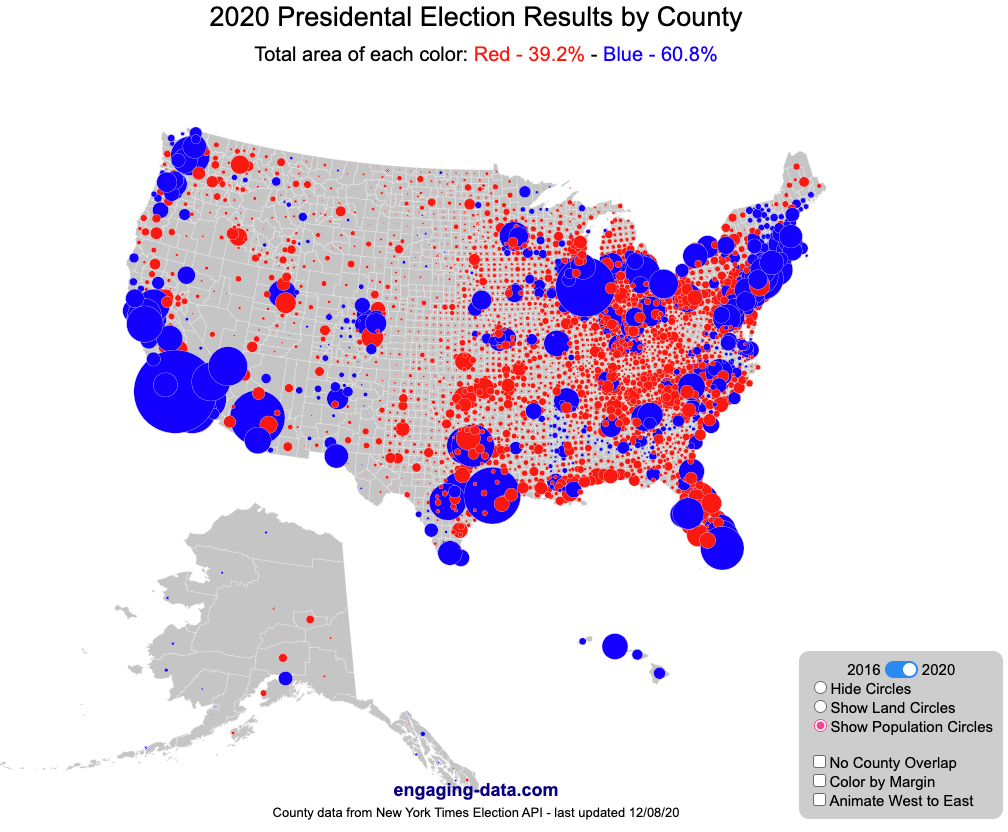

Beyond this, the Electoral College violates the most basic principle of a democracy: that everyone’s vote should be equal. Because electors are assigned partly by how many Senators each state has, and every state gets two Senators regardless of its population, there’s an inherent inequality baked into the system. It’s a truism in politics that “land doesn’t vote, people do,” but under the Electoral College that’s not really true. States that consist mostly of empty land, like Montana and the Dakotas, have the value of their votes artificially inflated because they have two Senators, while states with a high population have their votes artificially devalued. This is what the 2020 vote for president looks like when you account for population:

Notice all the empty gray in the middle where nobody lives? Because of the Electoral College, those areas still count the same—or more than!—places with many more actual human beings. In a scathing editorial called “How Many Californians is Your Vote Worth?,” Paste Magazine writer Geoffrey Himes breaks down the math:

Think of it this way. If you were a voter in Cheyenne, Wyoming, in 2016, your vote was worth 1/85,283rd of one Electoral vote (255,849 total votes divided by three Electoral votes). By contrast, if you were a voter in Los Angeles, California, in 2016, your vote was worth 1/257,847th of an Electoral vote (14,181,595 votes divided by 55 Electoral votes). In other words, a Wyoming voter’s ballot was nearly four times as powerful in electing a president as a California voter’s ballot.

Even reforming the “winner-takes-all” system to a more proportional one, like Maine and Nebraska’s, wouldn’t fix this. It’s a fatal flaw in the concept of the Electoral College itself.

Debates about electoral votes and proportional representation are often pretty abstract and nerdy, but these issues are deadly serious. Because of the Electoral College, it’s possible for a presidential candidate to lose the popular vote in the United States, but still become president. This has happened twice in the 21st century alone, ushering in George W. Bush in 2000 and Donald Trump in 2016. Each time, the margin of defeat was convincing: Bush lost to Al Gore by around 500,000 votes, while Trump lost to Hillary Clinton by roughly 2.9 million. Only the Electoral College bailed them out. And in each case, the consequences for the world were disastrous. Bush launched the invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan, two of the most devastating crimes of this century, and killed untold millions of innocent people. Trump’s litany of wrongdoing could fill a book (and has). If not for the Electoral College, none of it would have happened, and world history would be completely different.

That’s where the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact comes in. As Devon Hesano writes for Democracy Docket, the idea is surprisingly simple: each state in the Compact agrees to “award their Electoral College votes to the winner of the national popular vote, regardless of their own state’s results.” For now this is just an agreement on paper, but if and when the Compact reaches a critical mass of 270 electors among its members—the number required to actually become president—it’ll be activated. When that happens, the Electoral College would become essentially meaningless, although it would still exist as required in the Constitution. Whoever won more overall votes would be guaranteed to win the election—which, in turn, would require candidates to actually campaign in all 50 states to earn those votes. It’s an elegant solution to a thorny problem.

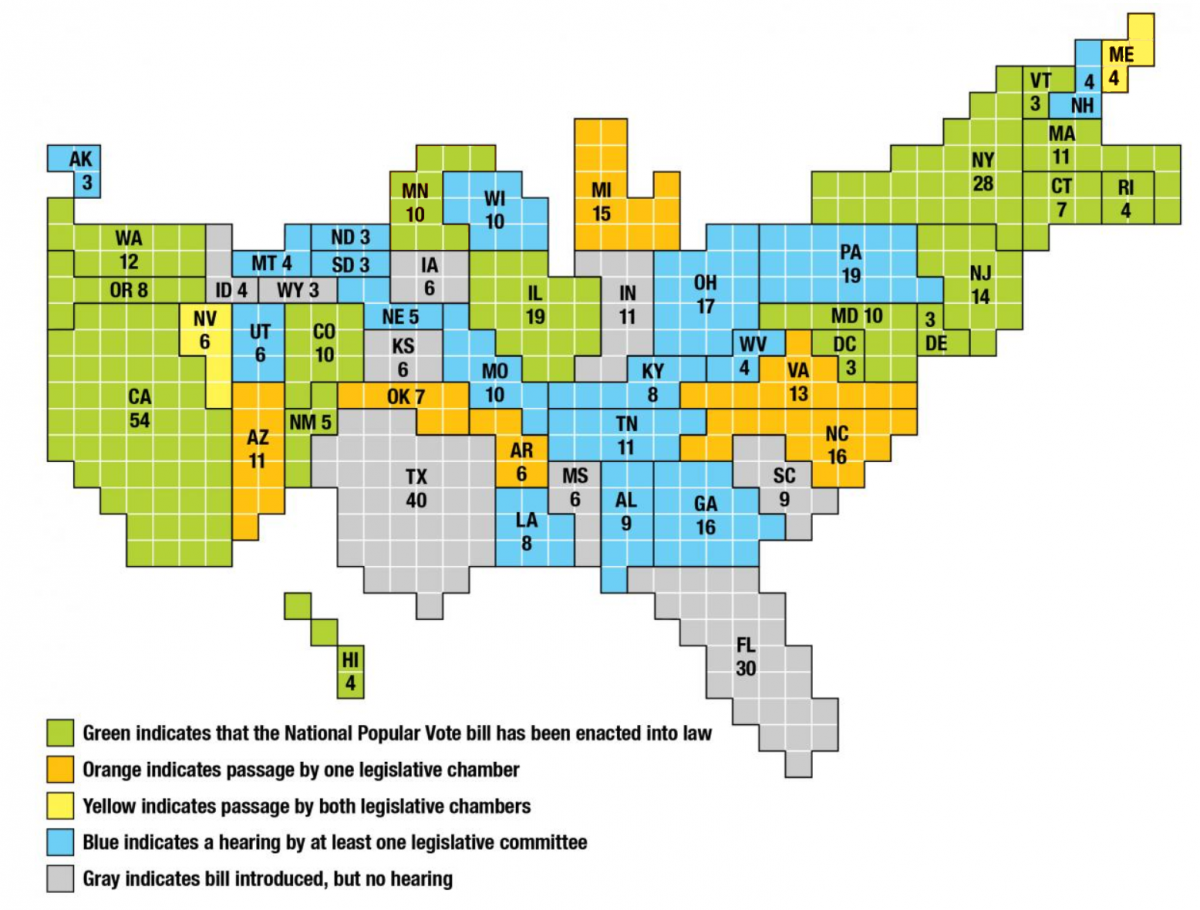

The idea for the Compact first came about, as you might expect, after the disastrous Bush v. Gore election of 2000. Bush was the first president to lose the popular vote since Benjamin Harrison in 1888, and a handful of legal scholars started cooking up a method to make sure it never happened again. The first was Robert W. Bennett of Northwestern University, who wrote a landmark paper called “Popular Election of the President Without a Constitutional Amendment” for an obscure legal journal called The Green Bag in 2001. (You can read the whole thing here.) The second and third were Akhil and Vikram Amar, who built on Bennett’s theory in a journal called Findlaw, also in 2001. In 2006, a Stanford computer scientist called John R. Koza wrote an entire book called Every Vote Equal to expand the theory further, founded a nonprofit organization called National Popular Vote to promote it, and successfully got legislation introduced in a handful of states. The Colorado state Senate was the first legislature to approve joining the Compact in 2006, and since then more states have slowly trickled in over the years. (The full, exhaustive history of National Popular Vote is available here.) Along the way, the movement has gained high-profile supporters like former Secretary of Labor Robert Reich, who’s been an enthusiastic booster. This somewhat ugly map shows the situation today:

As you can see, the Compact has been surprisingly successful. The coalition of states now includes most of New England and the entire West Coast, and currently has 205 total electors. That’s only 65 short of the magic number of 270, and Maine and Nevada have both voted to join, which would add another 10 electors.1There are also several states where one legislative body has passed a bill about joining the Compact, but not the other. (These are marked in orange.) As Stephen Wolf notes for the Daily Kos, it’s possible that the Compact effort could reach 270 electors as early as 2028.

Really, there are only two options here. You can have a true democracy, or you can have the Electoral College. You cannot have both. The National Popular Vote Interstate Compact has a boring name and an antiquated website, but it might be the best shot we have at serious electoral reform in this country. (The initiative has some slick resources for anyone inclined to help out too, like their “email your legislator” and “write a letter to the editor” pages.) The only real problem is that not enough people know about it. By all rights, a popular vote should be a core progressive demand along with a higher minimum wage and Medicare for All. The prospect of a never-ending stream of Bushes and Trumps who lose among actual voters but become president anyway is unacceptable. So is the idea that a voter in Los Angeles matters less than a voter in Wyoming or Montana. Let’s put the Electoral College in the bin where it belongs.

-

Nevada’s situation is a little complicated. They’ve passed an amendment to their state Constitution, which they have to pass again in 2025, followed by a referendum in 2026. It all seems very annoying. ↩