The Dystopias of Yesterday

Looking back on the disaster scenarios of vintage sci-fi.

There was a time when people told themselves very different stories than we do today. And they took those stories more seriously than readers and viewing audiences do today. They even kept a straight face at the end of science fiction movies when, after the alien invasion had been repelled, these words filled the screen: “The End…. or is it?”

I remember.

According to statistics, you are almost certainly younger than me. There were 2.6 billion people on Earth the year I was born; now there are 8.6 billion. Two-thirds of the people born that year are now dead. Nineteen out of 20 people in the world are younger than me. I have run aground on an alien planet. Sometimes I feel the urge to anchor myself in space and time like a traveler caught between dimensions.

Where am I from? Utica, New York, in the American Rust Belt. When am I from? From a time when there was an American Rust Belt. And so the story begins.

Remember Tomorrow

I was a sci-fi fanatic from an early age. From my earliest years, from the late 1950s on, I was addicted to the black-and-white science fiction movies on my family’s first TV. And I read as only a proto-nerd would read: obsessively. I read about distant futures and galactic empires, but I was especially drawn to futures I thought I might live to see.

There were space futures, which I rated solely on how impressive the starships were. There were super-civilization futures, with elaborate painted cities and hovercars flitting from one spire to another. (These were good.) There were future fascist states (bad, but with impressive uniforms and technology), interplanetary wars (bad, but also kind of cool), and nuclear apocalypses (bad, and not even remotely cool).

And there were low-budget dystopias, where it was obvious that the filmmakers didn’t have the money for special effects or set design. The future in those movies looked pretty much like 1965, but the cars were shaped a little differently and people carried little gadgets in their pockets. They weren’t the worst dystopias, but they were definitely bad. That’s the kind we live in now.

Sorry.

40 Years to Tomorrow

The big reveal in Philip K. Dick’s 1959 novel Time Out of Joint is that its main character isn’t living in the 1950s, as he thought, but in a future riven by nuclear war between humans on Earth and others on the moon. He has been tricked into believing he lives in that supposedly idyllic time because that future, and his role in it, are too terrible for him to accept.

The year is 1997.

A surprising percentage of 20th century science fiction falls into a category that might be called “40 years to tomorrow.” When writers wanted to portray a different but still recognizable future, they would set it 40 years after the date of publication, give or take a few years.

Harry Harrison’s 1966 novel Make Room! Make Room!, for example, describes an overcrowded and impoverished America of the 1990s. Forty years. Written at the height of “population bomb” fears, the novel’s American protagonist can only watch his television by rigging it up to a bicycle to generate power. The futuristic dystopia of Nineteen Eighty-Four was set 35 years from its publication date in 1949. Robert Heinlein’s 1958 short story All You Zombies (which you should really read) lets us know that time travel is available in 1993, 35 years later. 1953’s Fahrenheit 451 was set in the 1990s, another 40-year gap. Its author, Ray Bradbury said “I thought I was describing a world that might evolve in four or five decades.” He continues:

But only a few weeks ago, in Beverly Hills one night, a husband and wife passed me, walking their dog. I stood staring after them, absolutely stunned. The woman held in one hand a small cigarette-package-sized radio, its antenna quivering. From this sprang tiny copper wires which ended in a dainty cone plugged into her right ear. There she was, oblivious to man and dog, listening to far winds and whispers and soap-opera cries, sleep-walking, helped up and down curbs by a husband who might just as well not have been there. This was not fiction.

For Bradbury, born in 1920, a transistor radio and earpiece were science fiction of the highest order. They were for me, too, after I read those words. Those radios aren’t around anymore, which means one of my futures is now in the past.

10 Years is Forever

Other science-fiction futures used even shorter timelines, around the 10-year mark. Robert Heinlein’s 1957 novel The Door Into Summer describes a post-nuclear United States in 1970, which has technology for suspended animation, household robotics, and even a “zombie drug” for enslaving people. One of Bradbury’s Martian Chronicles stories, originally published in 1948, was set in 1960. A 1970 TV show called UFO portrays the world of 1980 as one of space commands, human-made flying saucers, supercars, and people who went to work dressed like members of KC and the Sunshine Band.

A classic of the 10-year subgenre is Frankenstein 1970, a movie that fascinated me as a child. The Wikipedia entry for this movie says “The title Frankenstein 1970 was intended to add a futuristic touch.” Oddly enough, it succeeded—for a movie that was released in 1958! When I saw it on TV in 1964 it definitely felt like a movie about the future, even though there were no real science-fiction elements in it.

The plot: Victor Von Frankenstein’s descendant (Boris Karloff) has been badly disfigured by the Nazis for refusing to help them. The Nazis, who had been defeated less than 15 years earlier, were and are the ultimate dystopian trope. Frankenstein is bitter and plans to get revenge by rebuilding his ancestor’s monster. But he needs an “atomic” reactor to do it, an allusion that was almost certainly inserted to fit the new title because, hey, won’t home—and castle—reactors be common by 1970?

Common, maybe, but not cheap. That’s why the Baron reluctantly admits a film crew into the castle to film a documentary. Chaos predictably ensues.

I remember being excited by the reference to 1970. It was the future, but it wasn’t so distant as to be unimaginable. Things would no doubt be very different, in exciting yet somehow recognizable ways.

Forty years, 10 years: why did those timelines matter? The sweep of those 40-year futures demonstrated how quickly people expected the world to keep changing. 1996 was expected to be radically different from 1956, with interplanetary flight a commonplace. Why? Because 1956 felt so different from 1916, at least in what were then called the “developed countries.” The 10-year timelines served another purpose. They broke this rapidly unfolding future into digestible bites.

1996? The mind boggles just trying to imagine it.

Engineering Über Alles

Robert Heinlein, a naval engineer turned science fiction writer, came close to the 10-year mark with a 1940 story called “The Roads Must Roll.” It’s prescient in predicting a 1950s-era national highway system, urban sprawl, and the need for solar energy. But cars on Heinlein’s superhighways can’t go slower than 60 mph.

The story is haunted by Heinlein’s obsessions. An oppressive federal government limits the use of fossil fuels. The answer? Massive systems of conveyor belts, reaching ultra-high speeds, connecting major urban areas and dramatically reducing the use of cars. People can work, shop, play, even have homes on these moving belts, or “roads.” And, of course, they can eat at:

JAKE’S STEAK HOUSE No. 4

The Fastest Meal on the Fastest Road!

“To dine on the fly

Makes the miles roll by!!”

But there’s trouble in paradise. It takes workers to operate the roads, and the workers have a union. The libertarian Heinlein’s union leaders are predictably corrupt and greedy. “Who makes the roads roll!” they shout to a rowdy and uncultured mob. “We do!” answer the (all male) workers. “Let ‘em yammer about democracy,” one speaker shouts. “That’s a lot of eye wash—we’ve got the power, and we’re the men that count!”

When they’re not singing militant songs (to the tune of “When the Caissons Go Rolling Along”), the workers instigate lethal sabotage at the behest of their tyrannical leader, “Shorty” Van Kleeck. Van Kleeck is finally defeated by his brilliant engineer boss, Chief Engineer Gaines, who—unruffled by his brush with death—snaps to a subordinate, “Get me a car, Dave, and make it a fast one!”

For all its radical technology, the most implausibly science fiction-y element in this story is that a union has that kind of power in 20th century America.

The Crazy Years

Heinlein’s 1941 novel Methuselah’s Children offers some headlines from a future 1969, during a period Heinlein describes as “The Crazy Years.” They include:

COURT ORDERS STATEHOUSE SOLD

Colorado Supreme Bench Rules State Old Age Pension Has First Lien All State Property

“U.S. BIRTH RATE TOP SECRET” — DEFENSE SEC.

CAROLINA CONGRESSMAN COPS BEAUTY CROWN

“Available for draft for President” she announces while starting tour to show her qualifications (Note: Although he was praised for his strong heroines, Heinlein could be sexist.)

IOWA RAISES VOTING AGE TO FORTY-ONE

Rioting on Des Moines Campus

LOS ANGELES HI-SCHOOL MOB DEFIES SCHOOL BOARD

“Higher Pay, Shorter Hours, no Homework—We Demand Our Right to Elect Teachers, Coaches.”

Ever the engineer, Heinlein prepared a detailed timeline for all his stories in a collection called The Past Through Tomorrow. How good were his predictions? In Heinlein’s fictional future, the 1960s saw “the first rocket to the moon” (so far, so good) and “mass psychoses in the sixth decade” (arguably true). But, contra Heinlein, the ’70s did not bring an “interregnum” followed by “a period of reconstruction… ended by the opening of new frontiers.” It did begin “a return to nineteenth-century economy,” in a predatory neoliberal fashion. However, Heinlein was probably picturing something quite unlike the rise of globalism and mega-corporations. Perhaps he was imagining the restoration of an imaginary frontier economy made up of mom-and-pop trading posts in far-flung settlement towns.

Nor did the 1980s and 1990s bring us the founding of Luna City, the “Space Precautionary Act,” the “Period of Imperial Exploitation,” the “Revolution in Little America,” “Interplanetary exploration and exploitation,” or the “American-Australasian Anschluss.”

Distant Futures

Imaginations were allowed to run free in the stories of more distant futures. Then, as now, those stories showed that science-fiction writers were capable of great feats of imagination when it came to science, but were often incapable of imagining different kinds of societies. The “space operas” used alien beings and technologies that could reshape the universe, but they leaned on well-worn human situations: medieval-style kingdoms, empires, cowboy-style shootouts, and galaxy-sweeping romances. One character or another was typically “Lord So-and-So,” while another would be somebody from a humble planet like Earth who was fast with a laser gun.

I was especially fond of E. E. “Doc” Smith’s Galactic Lensman novels, despite their flaws. Smith engaged with long sweeps of history, from billions of years in the past to the far future, placing humanity in a long sweep of interstellar social forces.

Another favorite was Olaf Stapledon, whose novels had unparalleled ambition. Last and First Men: A Story of the Near and Far Future tells the story of humanity today (which Stapledon calls “the First Men”) through the final stage of humanity (the “Eighteenth Men”). Alongside their scientific accomplishments, the Eighteenth Men have a variety of new gender classifications (or “sub-genders”) and are very open sexually, which appealed to my pre-pubescent and somewhat libidinous spirit.

My favorite writer of all, however, was Isaac Asimov, whose Foundation series tracked the rise and fall of galactic empires. These novels argued that, given enough data, a scientist could forecast future events—a science Asimov called “psychohistory.” The “father of psychohistory,” Hari Seldon, was capable of forecasting the time when an empire is at risk of collapsing, which was called “a Seldon crisis.” He is portrayed as an unparalleled genius—which meant, of course, that I saw him as a potential role model for, ahem, myself.

One of my favorite far-future stories is surprisingly down to earth. Asimov’s “The Feeling of Power” takes place during an interstellar war, long after humans have become reliant on technology and have forgotten how to do mathematics. One technician reverse-engineers an old computer and learns how to do calculations with a pencil and paper. His discovery becomes a military secret and leads to new forms of human-controlled weaponry, including kamikaze missiles, because human life is cheaper than technology.

I even wrote Asimov a fan letter when I was 12, along with a science fiction story I had written. I received a rather diplomatic postcard in return with a typed message and a handwritten signature: “Keep writing, Richard. Best, Isaac Asimov.”

My familiarity with Asimov came in handy when I interviewed economist Paul Krugman, with whom I had disagreed in print, during the 2009 financial crisis. To relieve the tension, I mentioned that I had read an interview where he said he wanted to become an economist after reading about Hari Seldon, because economics was the closest thing to “psychohistory” he could find. I reminded him of that and asked, “Is the United States in a ‘Krugman crisis?”

“I’m not that cosmic,” he answered.

Future While-U-Wait

Even the stories set in the present (the 1950s or early 1960s) showed us a kind of future, as the familiar world was suddenly transformed—by nuclear war, flying saucer attacks, or giant monsters laying waste to Japanese cities. Sci-fi films taught us that the present could become a hellscape overnight—which was certainly true at the height of the Cold War.

There were so many movies about nuclear radiation and apocalypse they run together in my memory. Day the World Ended had a goofy-looking monster. The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms had something about a lighthouse. Panic in Year Zero! had an exclamation point in the title. So did Them! That’s the one about giant ants; World Without End is the one about giant spiders. The H-Man was incomprehensible. Attack of the 50 Foot Woman was desirable. Fail Safe was for parents. On the Beach was too arty (that is to say, boring). I preferred the ones filled with roving, murderous mutants.

Where I lived, B-52 bombers would fly overhead on their way to nearby Griffiss Air Force Base. I made models of American and Russian jets, and when I heard a plane fly overhead I would go out to see if it was “one of ours” or “one of theirs.” But I was far from the coast, so I was safe from the giant radioactive octopus in It Came From Beneath the Sea.

Even then, it was understood that Japanese monster movies drew on the country’s recent trauma; they destroyed Tokyo again and again. My friends and I were especially fascinated by the tiny, telepathic twin singers who communicated by singing in Mothra. (I have since learned that they performed—life-sized—as “The Peanuts.”)

The alien-invasion classics include Earth vs. the Flying Saucers, where spaceships crashed into famous American monuments; The War of the Worlds, George Pal’s transplant of the H.G. Wells story into Southern California; and Michael Rennie as the alien peace envoy Klaatu in The Day the Earth Stood Still. (The short story it was based on, Harry Bates’ “Farewell to the Master,” has a good surprise ending that was left out of the movie.) When Worlds Collide shows humanity banding together to save itself from destruction, with scenes of a devastated earth as a rocket is prepared for the trip to its new home.

The idea that humanity would band together when faced with a common threat seems hopelessly naïve in an era when nations seem incapable of responding to climate change. But it was also the theme of The Outer Limits’ famous “The Architects of Fear” episode, where an astronaut agrees to be transformed into a monster and pretends to be an alien invader so that Earth’s countries will end their wars and band together.

Invaders From Mars is the one where a Midwestern boy sees a spaceship land in the field next to his house and nobody believes him. We watch the ground open up and swallow everyone he loves, turning them emotionless and deadly one by one. Its dreamlike quality and its play on primal childhood fears concludes when he wakes up and finds it was just a dream—only to once again see a spaceship landing in the field next door. “Gee whiz!” he exclaims.

They replayed it on TV once a year. I would walk next door to my friend Louie’s house, we would watch it, and then I’d walk back across the lawn expecting the earth to swallow me at any moment. Those 30 feet or so were the longest journey of my young life.

God in the Machine

Religious movies were another subset of the “future now” genre. In 1952’s Red Planet Mars, astronomers find evidence of intelligent life on Mars—and the Martians warn humans of the punishment they’ll face for deviating from Biblical teachings. Soon there’s deception, Cold War paranoia, and the overthrow of the U.S.S.R. by a theocracy. The final message is interrupted, but it begins “You have done well…” As in, “You have done well, my good and faithful servant.”

1950’s The Next Voice You Hear skips the middleman (or “middle-alien”) altogether, as the voice of God is heard on radios all around the world. The protagonists are the stereotypical “average American family” of movie lore—which is to say they’re white, middle class, and are named Joe and Nancy Smith, plus their son Johnny. (Mrs. Smith is played by future First Lady Nancy Davis.) We are never told why God needed to use the medium of radio to communicate with His creation.

The movie’s trailer says that The Next Voice You Hear “gets its Greatness from its Simplicity and its Humility.” The end credits read as follows:

“In the beginning was the Word: and the Word was with God: and the Word was God.” John Chapter I, Verse I

And then:

MADE IN HOLLYWOOD, U.S.A. by Metro~Goldwyn~Mayer

That’s humility, show-biz style. The studio got better billing than God.

Hideous but True

Parents in the 1960s often complained that “wholesome,” “moral” stories like these were being displaced by violence and grotesquery. It’s true that sci-fi stories became darker as time went on, and even mainstream programming increasingly leaned on the shock value of monstrosity. A case in point is the above-mentioned Outer Limits episode, “The Architects of Fear.” Some affiliates reportedly found that episode’s “monster” so frightening that they blacked it out during the original broadcast. They didn’t black it out in Utica and, trust me, it made an impression. A lot of the monsters who look silly today were terrifying at the time.

In a very different way, the Baron’s disfigurement in Frankenstein 1970 was also a sci-fi trope. Disfigurement represented a transformation of the self into something different and alien. Aliens and monsters were usually as ugly as the makeup artists could make them.

Ugly was different; different was scary; and scary was dystopian.

Worlds Within Worlds

The new-ish medium of television produced its own science fiction, of course, but its series tended to avoid full-scale dystopias, relying instead on “monster of the week” formats like The Outer Limits or ironic commentaries on human nature like those found in The Twilight Zone. Those programs had enormous impact, both on the general public and on me personally, but they didn’t necessarily fit either the dystopian or the far-future frameworks. Star Trek was set in a distant future, but pre-teen me was initially unimpressed. The spaceships didn’t look real, the uniforms seemed hokey, and the papier-mâché aliens were an affront to my dignity. Over time, the show wore down my resistance. But it wasn’t a future that felt tangible.

The Twilight Zone did have its dystopian moments. Dennis Hopper made an indelible impression as an American fascist guided by the phantom of Adolf Hitler in an episode called “He’s Alive.” In “Two,” a man and a woman from warring countries try to survive in a post-nuclear holocaust without being able to speak. In one of the series’ most famous episodes, “The Monsters Are Due on Maple Street,” aliens armed with only a small radio transmitter tear a small town apart by preying on the residents’ fears and prejudices.

The Outer Limits’ “Demon with a Glass Hand,” written by Harlan Ellison, brought its protagonist from a dystopian future into the present. It was hard to follow, but induced a kind of dream state that lasted long after it was over. The series also wrestled with then-new physics discoveries in “Production and Decay of Strange Particles,” when a form of radiation possesses nuclear plant workers and turns them into zombies. As the narrator says,

“Hidden deep in the heart of strange new elements are secrets beyond human understanding – new powers, new dimensions, worlds within worlds, unknown.”

Fast Forward

These accelerated timelines—10 years, 40 years—may seem absurd today. Does anybody think 2033 will be that different from today? But technological and social progress was moving rapidly back then. The 1940s saw global war, the defeat of the Nazis and Imperial Japan, the jet plane, the atomic bomb, and the rise of Communist China. The 1950s saw millions of people buy their first homes and cars, the Korean War, the hydrogen bomb, Sputnik (I remember hearing it beep on the family radio), the Cold War, a cure for polio, television, and the spread of mass consumer technology. The 1960s would bring the Space Race, the civil rights movement, lasers, more medical breakthroughs, assassinations, the antiwar movement, and humans walking on the moon.

There was no reason to think this pace wouldn’t go on forever. That’s why “1970” whispered to us of unseen wonders.

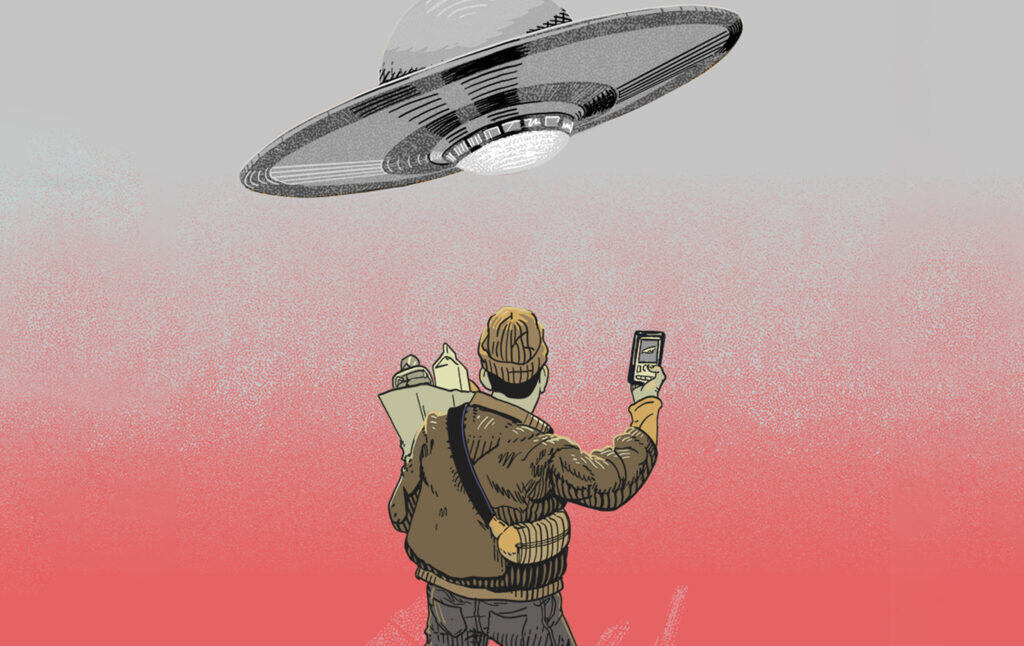

And here we are in a low-budget future—no flying cars, no interplanetary travel, no superintelligent robot friends. But is it dystopian? See for yourself: Pandemic. War. Racial conflicts and American fascism. Climate catastrophes that movie producers could present, low-budget style, using newsreel B-roll of past disasters. Even flying saucers are back in the news.

Gee whiz.

At its best, science fiction can teach us to recognize the future when it arrives. When it comes to their global impact, today’s mega-corporations pose the same kind of threat as runaway intelligences or alien invaders. Watching our response to the climate crisis, I have long thought about what “The Architects of Fear” and other stories got wrong: if aliens invaded today, humanity would not come together to fight them. Corporations would make deals with them and, as in the recent film “Don’t Look Up,” other people would deny their existence. (Interestingly, Paul Krugman also mentioned “The Architects of Fear” in an interview during the financial crisis, suggesting a fake invasion might be a good ploy for passing some fiscal stimulus spending.)

We know what science fiction got wrong. But despite my parents’ concerns, my absorption in it has shaped me and others in extremely valuable ways—especially now. We live in a time when the human imagination has been constricted by a global economic system that’s determined to tell us that, in Margaret Thatcher’s words, “there is no alternative.” Science fiction shows us that there is always an alternative. It’s not surprising that there was a strong leftist theme throughout Asimov’s writing, or that Stapledon was a self-described socialist.

The world can be remade. I know. I was inside the Soviet sphere when it collapsed, which it did in the manner of Lenin’s dictum: “There are decades where nothing happens; and there are weeks where decades happen.” Lenin’s observation is still true. The elite political consensus is eroding all around the world. That creates the potential for radical change—either global advancement or global collapse—something which could take decades to unfold or might happen faster than we can imagine. Sci-fi taught me to remain open to the possibility of ever-living radical transformation. And ideas like those in Asimov’s pencil-and-paper story made it easier for me to understand and embrace thinkers like Ivan Illich, the 20th century philosopher who promoted the use of “appropriate technology” over resource-intensive corporate products.

“I’m not that cosmic.” Well, I am. You probably are, too. I give science fiction a lot of credit for that. In 2011, I went back to Utica after a 40-year absence. Large parts of the city had been left in ruins by the collapse of industry, and it had become a major refugee resettlement area. Here’s how I described myself then: “A man (wears) black clothes of no known 1950s fashion. A headset flashes in his ear. The object in his hand links him to the entire world. He’s an emissary from my childhood’s future….”

Everyone’s future begins as a nearly infinite array of possible timelines. But each narrows down into one. This is mine. Trust me, yours will be interesting—filled with new powers, new dimensions, worlds within worlds. But my world won’t change very much. As far as my path to the future is concerned, this is the end.

Or is it?

_(20145706174)%20(1).jpg?width=352&name=Berea_College_20101122_FoodService_LK(23)_(20145706174)%20(1).jpg)