Abolish the Tipped Minimum Wage

Service workers deserve a real livable wage. How is this even up for debate?

This article was expanded from an item in the Current Affairs Biweekly News Briefing. Subscribe today!

Earlier this month, service workers and labor activists gathered in Annapolis, Maryland, to make a demand of their lawmakers. What they wanted was simple: to get rid of the state’s tipped minimum wage. Sometimes called the “subminimum” wage, this is an enormous carveout in U.S. labor law which applies in many states. In simple terms, it sets a separate minimum wage for workers who traditionally receive tips—often people who work in restaurants, like bartenders and waitstaff—which is below the already-low federal minimum wage of $7.25 an hour. Nationally, this “subminimum” is just $2.13 an hour, and 18 states and territories don’t require employers to pay anything above that. In many other states, the tipped minimum is only marginally better; Maryland’s, for instance, is $3.63. In fact, when Maryland raised its minimum wage to $15 this year, the legislation included a special “exception” to exclude tipped workers. (Hence the Annapolis rally.) Over the years, business owners and their allies in the press have made a variety of arguments to defend this practice. But they’re all nonsense. The tipped minimum wage is absurd, unjust, and harmful, and it needs to go.

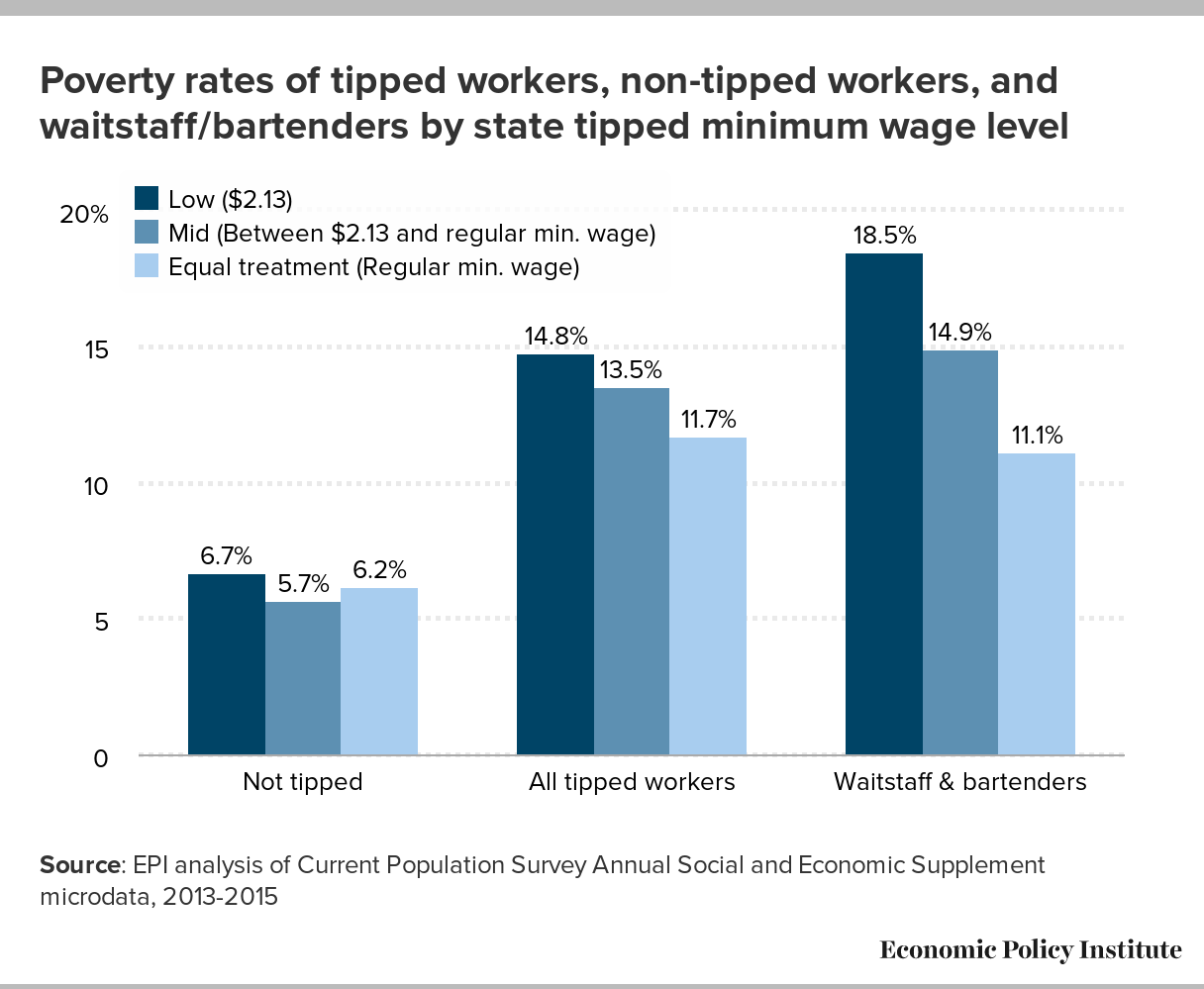

To begin with, there’s the obvious economic argument. In real terms, $2.13 (or $3.63) is nothing. Chicken scratch. You might as well not be getting paid at all, because you can’t buy anything substantial for that amount—in the case of restaurant workers, not even a meal in your own workplace. In theory, there’s a remedy for this: if a worker’s hourly tips don’t add up to the regular minimum wage, employers are supposed to make up the difference. (This is called a “tip credit.” The details are a bit complicated and vary depending on the state.) But in practice, this compensation often doesn’t happen. As the Economic Policy Institute notes, “enforcement of this requirement is fraught with problems, and evidence suggests that tipped workers are subject to high rates of wage theft” across the country. In a 2010-2012 enforcement effort by the Department of Labor, “83.8 percent of investigated restaurants had some type of violation,” amounting to “$56.8 million in [unpaid] wages for nearly 82,000 workers.” (And those are the wages the Department was able to identify and recover—the actual figure was almost certainly higher.) The EPI also points out a direct link between the tipped minimum wage and increased poverty rates. In a data set from 2013-2015, “18.5 percent of waiters, waitresses, and bartenders” lived in poverty if they worked in a state that required only a $2.13 tipped wage, compared to only 11.1 percent in the handful of states where the tipped and regular minimum wage are the same. Shockingly, when you’re paid low wages, you end up poor.

The more insidious problem, though, is the power dynamic a tipped wage creates. In a workplace with a standard rate of pay, customers’ power over the workers is limited: they can complain to the manager, and they frequently do, but that’s usually as far as it goes. But with a tipping-based system, the customer directly controls whether the worker gets their income or not, which opens all kinds of possibilities for abuse. One of the most prominent slogans used by One Fair Wage—the preeminent workers’ group around this issue—is “We Are Not On the Menu,” a reference to the rampant sexual harassment tipped workers are often forced to deal with. Speaking to reporters from The Counter, Gemma Rossi—one of the group’s organizers and a former waitress—describes the situation as she’s seen it:

If somebody makes an inappropriate comment to you, or if somebody asks you for your phone number, or if somebody touches you inappropriately, those are things that, if you speak up, could potentially affect your income. You are stuck in this predicament[….] If I want to be paid, I have to endure this.

Rossi’s experience, unfortunately, is a common one. For Jacobin, Alex Press notes that “76 percent of tipped workers [experience] harassment, compared to 52 percent of non-tipped workers.” (It should go without saying that the number should be zero.) And according to 2013 data, tipped workers are disproportionately women, with 66.6 percent identifying as female compared to just 33.4 percent male. So not only is the harassment skewed along gender lines, but the economic harm is, too.

Even when they’re not being outright creeps, customers can just be jerks. In some cases, they’ll leave an insultingly low tip—or none at all—to punish workers for some perceived slight, or simply because they can. In 2019, Buzzfeed published a list of ridiculous things restaurant customers have left instead of a tip, and it’s genuinely infuriating. The worst examples include a fake $100 bill with Barack Obama’s face on it, arcade tokens, an unopened condom (oh look, harassment again!), a shrugging emoji scrawled on the receipt, and the words “use an umbrella when it rains.” What, if anything, are people thinking when they pull these stunts? Do they think it’s funny, or is it just petty cruelty? There’s no way of knowing, but getting rid of the tipped minimum wage would dramatically reduce the ability of random idiots to hurt workers’ take-home pay on a whim.

Of course, like most social and economic reforms, abolishing the tipped wage is fiercely opposed by the Wall Street Journal. You can form a perfectly coherent and principled politics by just reading the editorial page of the Journal and doing the opposite of whatever they recommend, and this is a prime example. In 2022, there was a heated debate in Washington, D.C., over a ballot measure called Initiative 82 which would gradually increase the tipped minimum wage to match the regular one over five years. In September of that year, the Editorial Board of the Wall Street Journal threw a tantrum about it, insisting that businesses couldn’t “withstand what would essentially be a threefold increase in labor costs over just five years,” and would “likely be forced to reduce hours, cut jobs, relocate to other jurisdictions or transfer higher costs to consumers.” But you’ll never guess what happened next: voters ignored the WSJ, passed the measure by an overwhelming 74 percent of the vote, and did not see an apocalypse in the restaurant industry. It’s true, some establishments have started charging extra service fees, allegedly as a result of Initiative 82—but to hear the WSJ tell it, you’d think restaurateurs would have started fleeing for the Virginia border, or charging $50 for a bagel. They haven’t. But D.C. service workers have benefited, with their wages actually growing faster than inflation between Jan. 2022 and Oct. 2023.

Really, the United States’ tipping system is a bizarre outlier in the wider world. In Japan, the custom of tipping is largely nonexistent, and workers in hotels and restaurants may even be insulted if you offer them a tip. In most of Europe, tips are considered an optional extra when service is really exceptional, not a core part of the pay structure. None of these places have any issue “withstanding” the expectation to pay their workers a normal wage. Like with so many other things, the United States is just uniquely bad in this regard. Yet again, the Wall Street Journal is lying through its gold-plated teeth.

So how did the U.S. tipping culture get started in the first place? Well, racism was involved. (In the United States, six out of every ten unexplained things are racism. The other four are high fructose corn syrup.) In an interview with Marketplace, One Fair Wage president Saru Jayaraman explains that the tipped minimum wage “has a pretty ugly and sordid history that relates to our original sin as a country”—slavery:

[P]re-emancipation of slavery, waiters in the United States were actually mostly white men, and they did not receive tips. They received wages. In fact, tipping had originated in feudal Europe. When it came to the United States in the 1850s, Americans rejected it. They thought it was a vestige of feudalism. They said, “We’re a democracy.” So in 1853, the white men who did not get tips got wages working as servers in Boston, Philadelphia and Chicago, [and they] went on strike. And, in response, not wanting to pay them higher wages, the restaurant industry started looking for cheaper labor. And after emancipation, they hit upon the idea of hiring newly freed Black people, Black women, in particular, coming up from the South. And [they told] them, “We’re not going to pay you, you’re going to exist on this thing that’s come from Europe called tips.”

Jayaraman is entirely right about the feudal origins of tipping. As Julia Larson writes for the drinks magazine Vinepair, the earliest form of the practice was something called “vail,” where “guests visiting large estates, typically owned by noblemen” in medieval Europe were expected to leave a small sum of money for the estate’s staff, as a gesture of noblesse oblige. Over time the feudal order was replaced by the capitalist one, and anti-Black racism became a more important element in the mix. As legal scholar Michelle Alexander wrote in a 2021 op-ed calling for the abolishment of the “racist, sexist subminimum wage,”

For Black women, the situation is especially dire. Before the pandemic, Black women who are tipped restaurant workers earned on average nearly $5 an hour less than their white male counterparts nationwide — largely because they are segregated into more casual restaurants in which they earn far less in tips than white men who more often work in fine dining, but also because of customer bias in tipping.

The fundamental logic of hierarchy, servitude, and oppression involved in tipping has always been a constant. Today, abolishing the tipped wage isn’t just a labor issue. It’s a civil rights issue, a race issue, and a gender issue.

Still, you could be forgiven for thinking the working class is divided on the subject. During the recent events in Annapolis, activists from One Fair Wage have been confronted by another, diametrically opposed set of activists who want to keep the tipping system. Many of them are from a group called “Save Our Tips,” and they even have a distinctive color scheme: the workers from One Fair Wage wear pink, while the pro-tipping ones wear green. Save Our Tips also campaigned against Initiative 82 in D.C.—in fact, the words “Vote No on 82” are still the first thing you see on their website. In Annapolis, they were vocal: “We’re happy with our tips. We’re not asking for anything,” said one. But Save Our Tips is not, in fact, a grassroots workers’ organization. It’s an Astroturf campaign started by a wealthy Republican consultant. In 2018, The Intercept published an extensive report about the group’s origins and funding, and it turns out it was originally “managed in part by Lincoln Strategy Group, a company that did $600,000 worth of work in 2016 canvassing for the Trump presidential campaign.” LSG, in turn, was co-founded by Nathan Sproul, a GOP operative with a long history of scandals behind him, including allegations of voter fraud; its original name was “Sproul & Associates.” So when the Intercept says that “‘Save Our Tips’ signs against the measure are now a ubiquitous presence in restaurants and bars” around Washington, D.C., that’s who was ultimately bankrolling them.

The world people like Sproul want to maintain is a bleak one. In it, millions of workers live in a constant state of tension, never sure of how much money they will (or won’t) make on a given day. They’re placed in a vulnerable position, where they may have to put up with harassment and abuse just to keep a customer happy, get a tip, and pay the bills. Racism and misogyny are embedded into the foundations of the entire system. But there is an alternative. In his account of the civil war in Spain, Homage to Catalonia, George Orwell relates what it’s like to live, work, and eat in a society controlled by working-class anarchists and communists, where:

Waiters and shop-walkers looked you in the face and treated you as an equal. Servile and even ceremonial forms of speech had temporarily disappeared. Nobody said ‘Señior’ or ‘Don’ or even ‘Usted’; everyone called everyone else ‘Comrade’ and ‘Thou’, and said ‘Salud!’ instead of ‘Buenos días’. Tipping was forbidden by law; almost my first experience was receiving a lecture from a hotel manager for trying to tip a lift-boy.

That’s a world worth living in. That’s the world we have to create, from the ashes of Sproul’s. Abolishing the tipped minimum wage won’t get us all the way there—not even close. But it’s a start. In the meantime, as the late Anthony Bourdain put it: “If you’re a cheap tipper, by the way, or rude to your server, you are dead to me. You are lower than whale feces.” Just keep that in mind.