What is Civilization?

The ‘Civilization’ game series inadvertently defines the exclusive club of ‘civilized’ people in the world as Western, European, and settler colonialist.

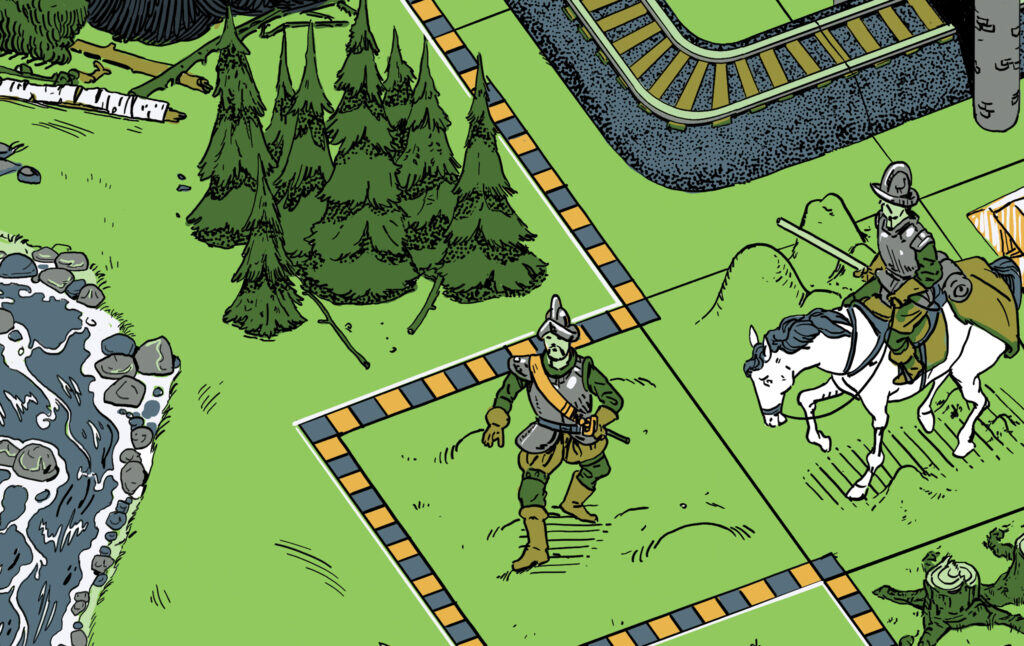

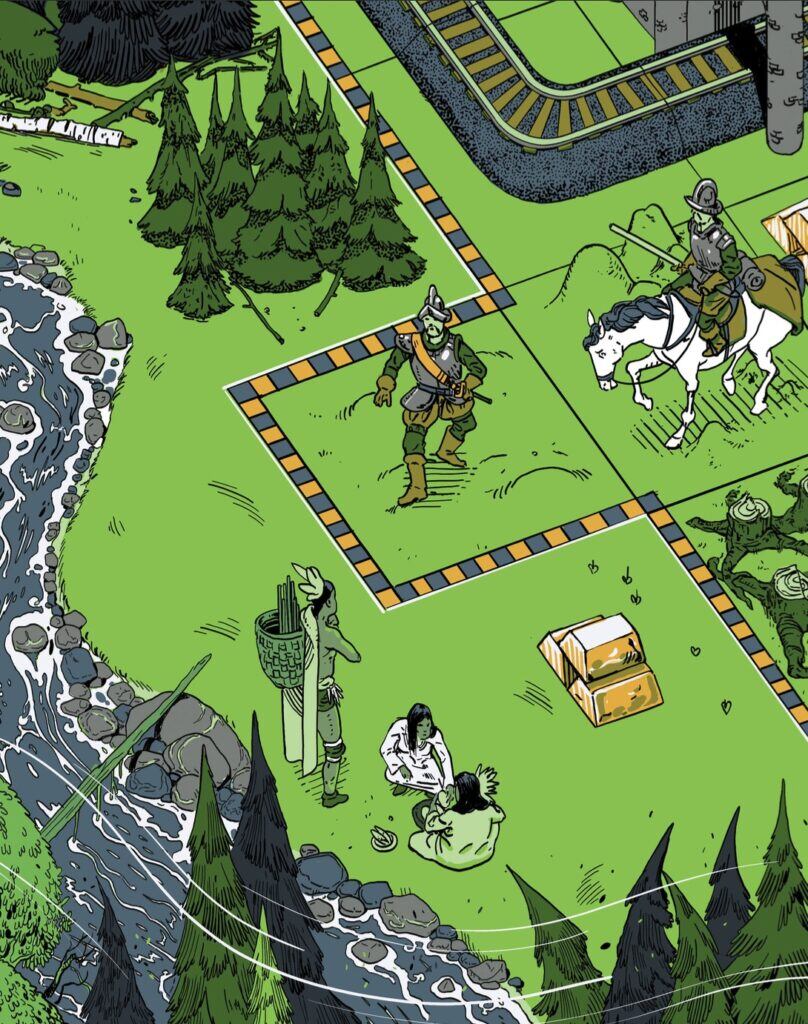

A tank battalion makes its final approach on Washington, D.C., each tank emblazoned with a light blue Mayan glyph resembling a tiger opening its mouth. The capital’s defenses have been worn down after a long, grinding bombardment from artillery and aircraft. All that’s left is to make the final capture, the culmination of generations of ceaseless war between the United States of America and the Maya civilization.

This is a scenario from the strategy computer game Civilization VI, a game where you can take control of various civilizations from history, including the Maya. Historically speaking, the game does take liberties. The people we call the Maya were not a relatively unified empire like the Aztec or Roman empires; they were more like a group of city-states that shared a similar culture, like ancient Greece. The developers simplify things, reducing the complex multipolar Mayan world into a single, unified “civilization” under a ruler called Lady Six Sky. The historical Lady Six Sky was an early medieval Mayan queen who ruled Wak Kab’nal, a city-state in modern Guatemala, ostensibly as regent for a series of male relatives. She survived for over 60 years in power, from a marriage alliance in 682 A.D. until she died in 741 A.D. (Remnant Game of Thrones fans will know how difficult that can be.) In the meantime, she managed to sack at least nine other cities and accumulate enough political capital and person-power to build monuments to her reign, which is why we know these things. I can’t help but think she would be confused, but gratified, that over 1,000 years after her death, she alone among all her rivals is remembered as the archetypal Mayan ruler, at least for players of Civilization VI. This is the kind of thing the Civilization series has been doing since it began, tailoring concepts from real history to create a sort of standardized “racetrack” of development and placing all human cultures at the same starting line.

The Civilization series, which made the name of now-famed game developer Sid Meier and coalesced a new genre of gaming, started in 1991 with the adaptation of a 1980 board game, also called Civilization. In this series, the player takes control of a nation from history, spanning the great powers of the ages from Rome to Egypt to China to the United States. Some civilizations (“civs” to the true gamers among us) have multiple leaders to choose from, each with specific traits and units meant to evoke their era. Would you like to play as Teddy Roosevelt, deploying “Rough Riders” and scoring bonuses for establishing national parks, or as Abraham Lincoln, who gets bonus military units for industrializing? These are among the thousands of choices, large and small, that go into building and expanding a civilization. You can win through science, by sending a colony ship to the distant galaxy of Alpha Centauri, through culture, by attracting tourists to your historical sites and museums, through diplomacy, by winning a series of votes at Civilization’s version of the United Nations, through religion, by converting all the other civilizations, and, of course, through warfare, by conquering the capitals of all other civilizations.

Conquest of one sort or another is at the heart of this particular gaming genre. The name usually given to strategy games like Civilization is “4X”, which stands for “eXplore, eXpand, eXploit, and eXterminate.” The unsavory connotations of these words may be why they are often abbreviated, though in the 1993 issue of Computer Gaming World where the term first appeared, “four X’s” was also a joking reference to the ‘XXX’ rating on pornography. There is indeed a kind of illicit thrill to playing these games as a postmodern, enlightened human being. Beyond the time suck factor (Civilization games are famous for the ‘one more turn’ phenomenon, which has led me to many semi-intentional all-nighters in my life), there is also the fact that nobody can see what decisions you make. You can direct the entirety of your economy to producing nuclear weapons while your subjects starve. You can create a lasting alliance with another nation, then stab them in the back as soon as they are occupied elsewhere. You can raze enemy cities to the ground, pillage the countryside, bombard farms and villages from afar, spy on your citizens, or even launch an inquisition to purge other religions. You can also play peacefully, developing your industrial capacity, making your farms more productive, investing in research, and building alliances, watching your people thrive and grow through the ages like a benevolent gardener. The goal, however, is dominance, however you achieve it. It is, of course, morally concerning that this is the goal, which Civilization somewhat obscures with its cartoonish art style and lack of the more traditionally criticized forms of video game violence. One reason I played so much of this series is that my parents did not allow me and my siblings to play first-person shooters. Little did they suspect that instead of embodying the lives of street murderers or soldiers, we were embodying the lives of war criminals, colonizers, and statesmen—a much greater scale of violence, perpetuated at a respectable remove.

Over time, your society starts to develop technologically, which gives you access to more buildings, governments, military units, and more. These technologies are organized in a “tree,” which is organized in a fairly linear way. The typical Civilization game starts at 4000 B.C., at which time your struggling hamlet is choosing between learning mining, pottery, or animal husbandry. What you choose first will influence which choices you have next. From that point on, every civilization progresses at different rates and in different paths, but through a standard path of development. In Civ VI, there is an identical process taking place with culture, which is related to the different forms of government you can adopt. This “tech tree” construct has been iterated upon countless times within the 4X genre in games like Stellaris, the Total War series, and Sins of a Solar Empire. It reveals certain assumptions about the way societies develop and the concept of progress. In the worlds of Civilization, there is an absolute measure of scientific, cultural, and even religious advancement for each civilization. (History buffs of 19th-century politics may recognize this as deeply reminiscent of the concept of “Whig History,” which held that societies move along a linear path toward “enlightenment” or a “glorious present.”) You can tell with absolute certainty whether you are ahead of your neighbor. The technological disparities quickly become apparent. It is not unusual in a game of Civilization to have a battle between an archer and a tank, or to start the space race in 1700 A.D. This creates an interesting dynamic. It implies that the world has an essentially meritocratic character. If technology progresses in a linear fashion along a predetermined path, and every civilization starts from the same point, then the success or failure of a given society on the field of play must be primarily a matter of its merits. The victors deserve to triumph, while the losers earned their defeat—a troubling notion in light of actual history.

This, and other fudging of the way history works, is necessary from a game design perspective. It wouldn’t be much fun to play as Poland, for example, and get endlessly divided between Germany, Russia, and whoever else could get a piece of the action. Instead, each civilization starts with one city and one warrior in 4000 B.C., even if they actually didn’t exist at that point. What would happen if Gandhi’s India and Hammurabi’s Babylon went to war with each other? Play Civilization to find out, sort of. Even the maps used are not the map of Earth, but a randomized map with characteristics you can set out beforehand. You can play with civilizations starting in their real positions on Earth, but for those of us who know a little geography (as many Civ players do), it takes some of the thrill of discovery out of the whole process. You’d already know what shape the continents take and who you are likely to find in each place.

There is the additional issue of Eurocentrism, in that most Civilization games have more European civilizations included than civilizations from other places, making Europe quite crowded and Africa and South America rather empty. The more recent offerings in the series have partially redressed this imbalance as well as gender imbalances, to the developers’ credit. The first Civilization featured 15 civilizations, only one of which was led by a woman (Elizabeth I of England). Six civilizations were European. In Civilization VI, there are 46 male leaders and 20 female leaders, a ratio that is significantly better than 14:1. (And, it must be said, a lot better than the current gender ratio of world leaders—just 13 of whom are female, among the 193 U.N. member countries). Out of 50 playable civilizations in Civilization VI, 18 are European, representing a modest improvement in diversity. Europe is still represented disproportionately to its size or population, which I believe is correlated with the games’ prescriptive conception of what it means to advance as a civilization. European societies and their global empires defined the concept of “civilization” as we understand it in the United States, using their own trajectories as a guide. In turn, these Eurocentric ideas form the criteria used by game developers to choose which civilizations to include. Societies that focused on territorial expansion, resource extraction, urbanization, and strict social hierarchies are more likely to be perceived as successful or important, and included in the games. The aforementioned 4X’s (eXplore, eXpand, eXploit, eXterminate) seem like a fairly accurate description of most European countries’ colonial efforts, at least by Civilization standards.

There is an essentially colonial aspect to this kind of game. That does not make them “bad” games or indicative of the moral character of those who enjoy them, but it does make it important to be aware of the ideological assumptions that underpin them. It also makes me feel indebted to the journalist who coined the term “4X,” Alan Emrich, whose analogy to pornography seems particularly apt. Civilization provides a sanitized, glamorized, airbrushed version of history, where an ageless intelligence pilots a nation like a marionette for 6,000 years. Everything is balanced, perfect, and transparent. Just as pornography takes an essential part of the human experience (sex) and stylizes and simplifies it into brain candy, Civilization stylizes the complex realities of world history into an enjoyable (and addictive) power fantasy.

I don’t think it’s coincidental that both 4X games and traditional pornography have been primarily aimed at men. A 2017 study by Quantic Foundry found that only 7 percent of gamers who play Grand Strategy games like Civilization are female. This makes sense, in terms of traditional gender norms and stereotypes. As men, we are often socialized to value conquest, expansion, power, and authority. The “great men” of history we learn about, both in school and the media, are largely military leaders with astronomical body counts (sometimes of both the military and sexual kinds).

There has definitely been a growth in the number of queer gamers, female gamers, and gamers of color, but it can’t be denied that “gamer culture,” if there is such a thing, used to be dominated by white, cis, straight men, just like much of the rest of our society. As a millennial cis white man disillusioned with war, nation-states, and toxic masculinity, I find that there is a transgressive thrill in virtually enacting the kind of ruthless world conquest that allegedly has no place in the world today. I salve my guilt in such playthroughs by selecting underdogs from history, imagining a world where the Maya, for example, last until the postmodern era and conquer Washington, D.C., the center of contemporary military and economic hegemony.

The conflict between the desire to reflect the diversity of humanity and the essentially Eurocentric structure of the Civilization games has even spilled into the real world. In 2018, Milton Tootoosis—a contemporary headman of the Cree Nation, a tribe that primarily resides in Canada and the northern United States—criticized the portrayal of Cree culture and the historical leader Poundmaker in Civilization VI. Tootoosis said that the game “perpetuates this myth that First Nations had similar values that the colonial culture has, and that is one of conquering other peoples and accessing their land,” and insisted that “that is totally not in concert with our traditional ways and world view.” In other words, the premise that Civilization games rely on and propagate is a common attitude among Westerners, which other cultures may not share. Because we in the United States come from a society and culture founded on genocide, we assume that all cultures and all “civilizations” share the desire to expand, dominate, and rule, which seems to us as natural as air and water. This faulty logic makes colonized peoples seem just as amoral as the colonizers, just a great deal less powerful. We have to oppress them, the logic goes, because they would oppress us if they could. One can imagine an American politician justifying conquering Lady Six Sky by conjuring this piece’s opening image of Mayan tanks on the White House lawn. This is how an occupying power with overwhelming force can make a resistance force seem like an existential threat.

This zero-sum view of the world makes sense for a conventional video game but is not how the world has worked throughout history. True, ancient empires formed in places like China and Rome, and conflict has always been a part of the human experience to some extent, but the formation of centralized state structures analogous to “civs” is actually somewhat uncommon. The only reason the modern nation-state is the way our world is currently organized is that European powers exported that model around the world during the first global colonial era. When Europeans were forced to give up their colonial possessions, the borders and governance structures they left behind persisted. There are countless other forms of social organization in history, from loose tribal confederations, to leagues of city-states, to pastoral nomadic groups held together by charismatic individual leaders. The idea of a nation with a distinct “spirit” that persists throughout history despite the turnover of leaders and populations is inextricably tied to the rise of nationalism in Europe in the 1800s. While there have been nation-like formations elsewhere in places like China, the age of imperialism and capitalism meant that European conceptions of nationhood and competition became hegemonic globally.

Today, it seems perfectly natural for individuals to identify as a member of a national community, forming what political scientist Benedict Anderson calls “imagined communities.” However, this is actually a fairly recent development. At different points in world history, it would have been far more natural to primarily identify with your religion, your tribe, your class, or even your occupation. Monarchs would come and go, and kingdom borders would change with them—this was before the modern identification of language and government that drove nationalism and today’s expectation of stable borders. For most of human history, empires were multiethnic, speaking many languages and encompassing many communities (think of the Austro-Hungarian empire, the Ottoman Empire, the Roman Empire, or the Aztecs). But when nationalism came of age in the early 19th century, people started to “sort” themselves into national communities. Think of the unifications of the formerly fractious Italy and Germany in the late 1800s. As part of this process, nations started to attempt to acquire communities outside their initial borders that spoke their main language (think of Germany and the Sudetenland in Czechoslovakia). The culmination of this process was World War II, in which German fascists went beyond colonizing non-Europeans and trying to absorb ethnic Germans abroad and began actively trying to colonize and exterminate other Europeans with military force and industrial efficiency. After that, there was an understandable desire to curb the excesses of nationalism, leading to the United Nations system and the eventual conversion of European colonies into European-style nation-states.

While Europe and East Asia had centuries of mutual warfare, resettlement, and diplomacy before arriving at their modern boundaries, Africa and the Middle East in particular were divided up based on European, not local, geopolitics. In many cases, European administrators who had never even visited the land in question drew completely arbitrary straight lines on the map, cleaving ancient communities from each other and placing bitter rivals in the same nation-state. (The infamous Berlin Conference of 1884, which divided Africa into nations with little regard for preexisting ethnic groupings, is one notable example.) In certain ways, the Civilization series puts the player in the position of such administrators, affecting countless lives and livelihoods with the click of a mouse. The arbitrary borders created by such decisions are often pointed to as a reason why warfare and political upheaval have been more common in these areas in the modern era. African and Middle Eastern ethnic groups have been randomly assigned categories that do not correspond to natural ethnic or geographic boundaries. This is one reason why there are no modern African nations in Civilization that don’t have a historic version, as many modern African nations are both geopolitically hamstrung by the legacy of colonialism and ethnically divided in a way that cuts against the idea of a national “spirit” Civilization is based on. Mali is based on medieval Mali under Mansa Musa, Egypt is based on Ptolemaic Egypt under Cleopatra, and South Africa is represented by the Zulu nation under Shaka Zulu, which no longer exists.

What this suggests to me is that the Civilization series inadvertently defines the word “civilization” itself. The initial enemies in the game are called “barbarians,” creating a dichotomy between “civilized” people and everyone else. This dichotomy is central to Western culture going all the way back to Herodotus, who coined the term. While the Civilization games allow many peoples into the exclusive club of “civilized” people that were excluded at some point or another, it still fits everyone into the basic framework. In this framework, “civilized” people are people who build dense, settled societies using agriculture and industry and then expand those societies with warfare, settler colonialism, or conquest. By using this framework, the games create a fantasy world, an alternate history where the world and its peoples started mostly at parity then started to diverge based on their own choices. It also places stateless people in an almost subhuman category. Without a flag to rally behind, they are barbarians. Unfortunately, this is how many people view the world to this day. It’s a hegemonic, popular, and comforting way to view the world. But as modern human beings living in a world of nations, we ought to remember that all of these structures are just that: arbitrary, human-created, with a specific history and trajectory. If we realize that, we can also recognize that they can change when they are no longer fit for purpose.