On MLK Day, Always Remember the Radical King

Forty years ago, the federal holiday celebrating Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday was created. While King’s legacy and holiday have been co-opted by presidents for political expediency, we must always remember King’s radical critique of U.S. society.

MLK Day 2020: I was packing a suitcase with snow boots and winter clothes for a trip to Des Moines while listening to Democracy Now!, which was playing excerpts from King’s “Beyond Vietnam” speech from 1967. I’d just quit my job and decided to be a volunteer canvasser for the Bernie Sanders campaign. Iowa, we canvassers were told, was where we needed to be ahead of the upcoming caucus—knocking on doors, connecting with voters, handing out literature.

I had never studied the writings or speeches of King, other than “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” in a college writing class on rhetoric. But just as I had been many years before in reading his “Letter,” I was struck by King’s analysis in “Beyond Vietnam.” King connected poverty, inequality, and materialism at home to militarism and injustice abroad, and he kept the focus on the poor and marginalized—both at home and abroad. He called for a “revolution of values,” a move toward a “person-oriented society” away from a “thing-oriented” society. It’s a heavy speech, but also one in which the clarity of King’s moral conviction comes through, and you can’t help but be moved by it.

Martin Luther King Jr. Day—also known as the MLK Jr. National Day of Service— falls on the third Monday of January each year and is one of 11 federal holidays in this country. A federal holiday is completely optional for states and the private sector. At my previous job in a private nonprofit, for example, we only started getting MLK Day off because the head of the organization made it a priority after Donald Trump came to power.

The King holiday is not nearly as institutionalized as other major holidays. According to government statistics from 2018, for the federal holidays of Christmas, Labor Day, Independence Day, and Memorial Day, the percentages of private and public sector employees who get those days off, paid, were in the mid-80s to 90s. Meanwhile, 86 percent of state and local government employees—and only 24 percent of private sector employees—received MLK Day as a paid holiday. (To be fair, George Washington’s birthday, also known as Presidents’ Day, achieves even lower numbers than MLK Day.) While all states celebrate MLK Day, two bizarre holdouts—Mississippi and Alabama—insist on holding a joint “King-Lee” day to simultaneously honor King and Confederate commander General Robert E. Lee. (This should actually be called the Civil Rights Hero & Racist Traitor Day.)

While there are many ways to spend MLK Day if, indeed, you have the day off—listening to King’s speeches, reading his writing, or engaging in a protest, march, or act of service—reviewing the history of King’s holiday itself is also worthwhile. To that end, I consulted Daniel T. Fleming’s fascinating 2022 book, Living the Dream: The Contested History of Martin Luther King Jr. Day. Fleming explains how the legislation to create the holiday was pushed through Congress—a 15-year effort, both impeded and aided by various conservatives—and how the holiday evolved over the course of four decades under various presidents as it received criticism from liberals, conservatives, and white supremacist groups. What emerges from the history here is not just how easy it is for people of any political stripe to co-opt MLK’s words and legacy for their own benefit. What also emerges is that the United States remains, fundamentally, a society direly in need of King’s structural critiques and moral leadership.

The King Holiday Act of 1983 was passed by the Reagan administration. President Reagan, creator of the now-infamous “welfare queen” trope—a “coded reference to black indolence and criminality designed to appeal to working-class whites” in his 1976 presidential campaign—was no proponent of racial justice. He had been against the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. But he was essentially forced to sign the legislation after it passed Congress. Fleming writes:

Reagan opposed the holiday until it became clear Congress would approve it by a large majority, at which point political reality dictated his signature. “Since they seem bent on making it a national holiday,” he said, “I believe the symbolism of that day is important enough that I would—I’ll sign that legislation when it reaches my desk.”

In 1984, Congress created a commission that would organize celebrations for the day and advise state and local governments and private organizations on how to celebrate the new holiday. Thus began the desegregation, as Fleming puts it, of the American holiday calendar. What a historic achievement—yet what horrible economic times, especially for the working class. As Reagan cut taxes for the rich, he cut social spending by over $22 billion in 1981 and 1982. As Fleming sums up: “The Reagan Revolution wreaked havoc on the Black working class.”

Given this austerity agenda, it’s probably not surprising that the King holiday commission was granted $0 in federal funding and would spend its short life begging for scraps from the private sector. The commission also expired every few years, had to be renewed by Congress, and faced defunding threats by conservatives over the years. (In a strange twist of events, the commission would dissolve itself in 1995 just as King’s widow, Coretta Scott King, stepped down as the head of the group and allowed her son, Dexter King, to replace her. With the commission no more, then-President Clinton tasked his own community service organization, now AmeriCorps, with responsibility for promoting the holiday.) What’s also not surprising is how viciously Reagan co-opted King to promote his own reactionary agenda.

In reviewing the history of the legislation under Reagan, Christopher Petrella and Justin Gomer put it bluntly in the Boston Review: “Reagan Used MLK Day to Undermine Racial Justice.” Explaining Reagan’s about-face on the legislation, they write:

Yet even after he publicly changed his position, Reagan wrote a letter of apology to Meldrim Thomson, Jr., the Republican governor of New Hampshire, who had begged the president not to support the holiday. His new position, Reagan explained in the letter, was based “on an image [of King], not reality.” Reagan’s support for the federal King holiday, in other words, had nothing to do with his personal views of the civil rights leader. Instead the holiday provided Reagan with political pretext to silence the mounting criticism of his positions on civil rights. By 1983 Reagan faced an onslaught of criticism from groups such as the NAACP and the Urban League for his aggressive assaults on affirmative action and court-ordered busing. With a reelection bid on the horizon, he began to make more concerted efforts to pacify his critics and soften public opinion over his open hostility to civil rights. The King holiday was the primary component of this effort.

Reagan’s pivot on the King holiday provided a two-pronged benefit. On the one hand it would pacify critics of his positions on civil rights, but on the other it enabled Reagan to position himself as the inheritor of King’s colorblind “dream”—a society in which “all men are created equal” and should be judged “not . . . by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character”—in order to advance the anti-black crusade he had waged since the 1960s, now under the alluring mantle of colorblindness.

Fleming goes on to detail how Reagan’s belief in colorblindness happened to be aided by Coretta Scott King’s vision that the holiday be promoted as one for all Americans, not just Black people: “Though Coretta’s motivations differed from theirs, her insistence that King Day was not a Black holiday dovetailed with the Republican agenda of downplaying the need for ongoing civil rights initiatives.” After all, Reagan had likened affirmative action to “Jim Crow segregation.” Furthermore, Reagan appointed Black conservatives to the commission in an effort to undermine its potential radicalness. Those conservatives would “ensure King’s radical challenge to economic inequality remained unacknowledged in official celebrations.” (Also notable: activist peers of King were deliberately left off the commission.) The conservative agenda of that time conceived of integration as a process of Black people integrating into capitalist society as individuals. They completely ignored King’s structural critiques of capitalism. Reagan also promoted the idea that King’s work had essentially been completed. King had pointed out an injustice, and the nation had fixed it. Case closed.

Fleming explicitly points out that one line from King’s “I Have a Dream” speech (which was the original, “uplifting” focus of the holiday) is often “cherry-picked” by the right:

[S]pecifically, “I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.” Conservatives claimed this as proof King would have opposed affirmative action, which they argued divided Americans by the color of their skin.

This is something conservatives are still doing. Ron DeSantis quoted King’s dream to justify his Stop WOKE Act in 2021. Former Secretary of Housing and Urban Development Ben Carson referenced the speech in a 2013 op-ed criticizing the Black family. And Ben Shapiro, who has said King made the “greatest American speech of the last 100 years,” managed to make a huge mess of it, saying that King’s dream was to “embrace group redistributionism and racial discrimination,” but that “isn’t the dream or the pathway we celebrate him for.” But as anyone who reads the “color of their skin” quote closely will realize, King did not say that he wishes his children would not be seen or recognized as Black, which is presumably the kind of world conservatives think we live in. He just wishes that the melanin content of their skin wouldn’t be the basis of (presumably negative) judgment against them.

Subsequent presidents put their own individual touches on the co-optation of King. Recall that George H. W. Bush hardly had a good record on race. He had come to power aided by a racist, fearmongering ad that was released against his opponent, Michael Dukakis. The ad used the case of one Black prisoner, Willie Horton, who had committed crimes while on furlough, to imply that Dukakis was soft on crime. Fleming concludes that King was distorted similarly by both Reagan and Bush. The administrations seemed to operate under the “myth that the United States had transcended its racist history, thus rendering government activism in race relations unnecessary, [which] was central to this reimagining of King.”

For George H.W. Bush, the reimagining of King was most prominent in the area of foreign policy. It must be remembered that King was a staunch pacifist and anti-imperialist. Fleming notes how Bush linked King to uprisings in China and Eastern Europe in 1989 in order to imply that King was anti-Communist—truly ironic, as King himself had been smeared as a Communist in his lifetime, a point that the FBI had to finally concede was untrue in hearings prior to the passage of the holiday legislation.1 In a period when Bush would wage devastating wars in the Middle East, he “deployed King’s image to influence South African politics….[He] urged resistance leader Nelson Mandela to ‘adopt the nonviolent tactics of Martin Luther King’” while opposing economic sanctions against that country, which King had supported.

At the same time, Bush publicly supported the holiday and gave the commission funding, although some conservatives, including Newt Gingrich, threatened to defund or retire the commission at times. Unfortunately, the commission of this era also did some “reimagining” of its own. They released advice on “right and wrong” ways to celebrate the holiday, going so far as to discourage civil disobedience and protests about particular issues (such as abortion).

The next president, Bill Clinton, actually had some credibility among African Americans (although support for him was by no means universal in the Black community). So his use of King is particularly notable. Clinton came into office as a so-called New Democrat, one who wasn’t afraid to be “tough on crime” like conservatives. Clinton instituted welfare reform—an “end [to] welfare as we have come to know it”—and passed the 1994 Crime Bill, each of which caused great harm to Black Americans, the latter contributing to the mass incarceration of Black men in particular. Unlike Reagan and Bush, for whom King’s work had been finished, Clinton admitted there was work to be done in terms of racial understanding and economic and educational opportunity. But the distortion of King was in the details: the work would be done not by structural changes but by individual acts of service.

Under Clinton, the MLK holiday was refashioned from “Living the Dream” into community service with the King Holiday and Service Act of 1994. The commission would promote activities such as working in soup kitchens, tutoring kids, or helping the homeless. Instead of “the dream,” the focus would be on King’s 1968 sermon, the “Drum Major Instinct,” in which he said that “everybody can be great, because everybody can serve” their society. Fleming notes:

By using the drum major image, [holiday] reformers encouraged Americans to emulate King with simple deeds, and they hoped to highlight and alleviate major problems of the era, such as crime, swelling prison populations, teen violence, and gang warfare.

The orientation of the holiday toward the “Drum Major” theme was part of a larger effort by Clinton to promote community service, which Fleming says served multiple purposes. It went hand in hand with personal responsibility, which Clinton noted in his inaugural address; it embodied the act of people of different racial and ethnic backgrounds coming together to increase mutual understanding; and it could, according to Clinton, even help the economy.

Fleming asks if the service focus was actually a “Trojan horse for neoliberal economic policies.” It sure sounds like it. Fleming quotes Clinton directly: “The era of big government may be over…. the era of big challenges for our country is not, and so we need an era of big citizenship.” Hence the perfect conditions under which Clinton could “hollow out the welfare state,” as Jason Resnikoff puts it in Jacobin.

The other part of the story here is that the passage of the Service Act came about in a racist way. In order for conservatives to support the legislation, it had to be framed in conservative terms. What could be more classically conservative than the pathologizing of the Black family and Black culture and a fearmongering over youth violence?

As Nathan J. Robinson wrote in Superpredator: Bill Clinton’s Use and Abuse of Black America, Clinton would embrace these conservative tropes directly.

In a 1993 speech in front of 5,000 African Americans at the Church of God in Christ, Clinton explained that if Martin Luther King were still alive, he would be extremely disappointed in them:

“If Martin Luther King.… were to re-appear by my side today and give us a report card on the last 25 years, what would he say? You did a good job, he would say, voting and electing people who formerly were not electable because of the color of their skin… You did a good job creating a Black middle class of people who really are doing well, and the middle class is growing more among African Americans than among non-African Americans. You did a good job in opening opportunity. But he would say, I did not live and die to see the American family destroyed.… I fought for freedom, he would say, but not for the freedom of people to kill each other with reckless abandonment, not for the freedom of children to have children and the fathers of the children to walk away from them and abandon them, as if they don’t amount to anything.… This is not what I lived and died for. My fellow Americans, he would say, I fought to stop white people from being so filled with hate that they would wreak violence on black people. I did not fight for the right of black people to murder other black people with reckless abandonment.”

Robinson sums up:

By making an issue of “black on black crime” and the perceived decline of black fatherhood, Clinton echoed conservative rhetoric about the dysfunctions of black life, attributing problems in the black community to the failure of blacks themselves to exercise personal responsibility.2

Things got even more grotesque during the reign of George W. Bush, who, in a 2002 King holiday proclamation, said the country was “rededicating ourselves to Dr. King’s dream” as the 9/11 attacks had “drawn us closer as a nation.” (To which Fleming responds, “King did not dream of a War on Terror.”) He also compared the people in the civil rights movement to New York first responders, a truly odd comparison. And Bush fetishized the “skin color” line by using it in four of his subsequent proclamations.

President Barack Obama’s historic win (and the hope of so many for profound change) was, of course, tempered by his ineffective response to the 2008 financial crisis, the Occupy movement, and the rise of Black Lives Matter in response to continued police brutality against Black people. (BLM activists would criticize the service holiday as not being up to task as a response to racial injustices including police violence and poverty.) Fleming’s section on Obama notes the depoliticized platitudes that the president offered up around King. In one 2017 speech after Trump’s election, Obama did the thing that Luke Savage and Nathan J. Robinson have identified as “fraudulent universalism.” He “used King to urge Americans” to, in Obama’s words, “assume the best in each other.” Fleming continues:

He took aim at both activists and conservatives…. [He] used civil rights movement history to both argue that progress had occurred and not enough progress had occurred. If one argued too forcefully against either proposition, they disrespected the movement.

In an on-brand move, President Trump used a 2018 proclamation to portray “King as an almost entrepreneurial figure” and said that he would help bring funds to minority and women entrepreneurs.

As for President Joe Biden, he has lied so many times about his involvement in the civil rights movement that we need not take too seriously any of his thoughts on King or anything pertaining to race more generally. In any case, here’s a snippet of what Biden said in his 2023 MLK Day remarks:

We have to choose a community over chaos. Are we the people who are going to choose love over hate? These are the vital questions of our time and the reason why I’m here as your President. I believe Dr. King’s life and legacy show us the way we should pay attention. I really do.

It’s hard to see how Biden is following “the way” of King as he continues support for war in Ukraine and a genocide against Palestinians. Nothing but empty platitudes here.

When the commission refashioned the holiday as a day of service, they were inspired by King’s “Drum Major Instinct” sermon. In that sermon, King said, “everybody can be great, because everybody can serve” their society. On the surface, this connection to volunteerism makes sense. But the ideas in the sermon go much deeper than volunteerism. If you haven’t listened to it, I suggest you take a listen. It’s a magnificent 40-minute oration in which King demonstrates the kind of righteous indignation that is motivated by a simultaneous anger at injustice and a love of humanity. He skillfully takes us from what seem to be harmless personal habits to the threat of nuclear annihilation. He connects the individual to the societal, suggesting how certain behaviors that are promoted in our culture can scale up to the level of entire nations. In sum, it’s about how we all possess the human “drum major instinct” to be important, loved, and distinguished. On the individual level, this can show up as conspicuous consumption, keeping up with the Joneses, or even lying to promote oneself. It can also show up as racism.3 At the group level, this shows up in membership in classist, exclusive organizations like country clubs, fraternities, or churches. And at the level of nations, this shows up as superpowers vying for domination: “I must be first! I must be supreme!” King quotes nations saying to each other. But the threat of nuclear annihilation is real. And if people cannot hold in check their “drum major instinct,” King argues, we could destroy ourselves entirely.

Similar to the way he reframes his opponents’ claim that he is “extremist” in his Birmingham Jail letter—where he recasts himself as an extremist for love and truth—King reframes the drum major instinct as something that can be harnessed for good. Paraphrasing Jesus, King says:

Yes, don’t give up this instinct. It’s a good instinct if you use it right. It’s a good instinct if you don’t distort it and pervert it. Don’t give it up. Keep feeling the need for being important. Keep feeling the need for being first. But I want you to be first in love. I want you to be first in moral excellence. I want you to be first in generosity. That is what I want you to do.

At the end of the sermon, King’s voice gets calmer, and he talks about how he wishes to be remembered on his death.

[W]hen I have to meet my day, I don’t want a long funeral. And if you get somebody to deliver the eulogy, tell them not to talk too long. And every now and then I wonder what I want them to say. Tell them not to mention that I have a Nobel Peace Prize—that isn’t important. Tell them not to mention that I have three or four hundred other awards—that’s not important. Tell them not to mention where I went to school.

I’d like somebody to mention that day that Martin Luther King, Jr., tried to give his life serving others.

I’d like for somebody to say that day that Martin Luther King, Jr., tried to love somebody.

I want you to say that day that I tried to be right on the war question.

I want you to be able to say that day that I did try to feed the hungry.

And I want you to be able to say that day that I did try in my life to clothe those who were naked.

I want you to say on that day that I did try in my life to visit those who were in prison.

I want you to say that I tried to love and serve humanity.

Yes, if you want to say that I was a drum major, say that I was a drum major for justice. Say that I was a drum major for peace. I was a drum major for righteousness. And all of the other shallow things will not matter.

There’s a quote from the Bhagavad Gita that can be loosely interpreted as such: we are not entitled to the fruits of our labor, only our labor. Now, I definitely do not believe this is true in a literal, economic sense—we are most certainly entitled to the fruits of our labor, and the struggle for socialism is, in part, a struggle to obtain the fruits of human labor which have often been denied us by the rich and powerful. But what I like about the quote is that it reminds us that we aren’t guaranteed a particular outcome in our work. If people only struggled against injustice because they felt certain of a win, there would be no struggles, and there would be no wins, big or small. We have to try because it is the right thing to do. We have to try, and this is bigger than being important, looking good, or achieving fame. This is what I hear in King’s “Drum Major Instinct.” I tried to give my life serving others.

At one point in the book, Fleming asks, “Can a holiday be radical?” Surely the answer is complicated. If presidents and leaders can twist King’s words in order to suit agendas that King would have been against, then, Maybe Not. But I also believe something the historian Howard Zinn once said: “You read a book, you meet a person, you have a single experience, and your life is changed in some way. No act, therefore, however small, should be dismissed or ignored.” A holiday may not be radical, but it can still radicalize. How we spend the King holiday—and, indeed, our lives—is up to us. And it’s always a good time to be radicalized by engaging with King’s work, or to radicalize someone else by sharing it with others.

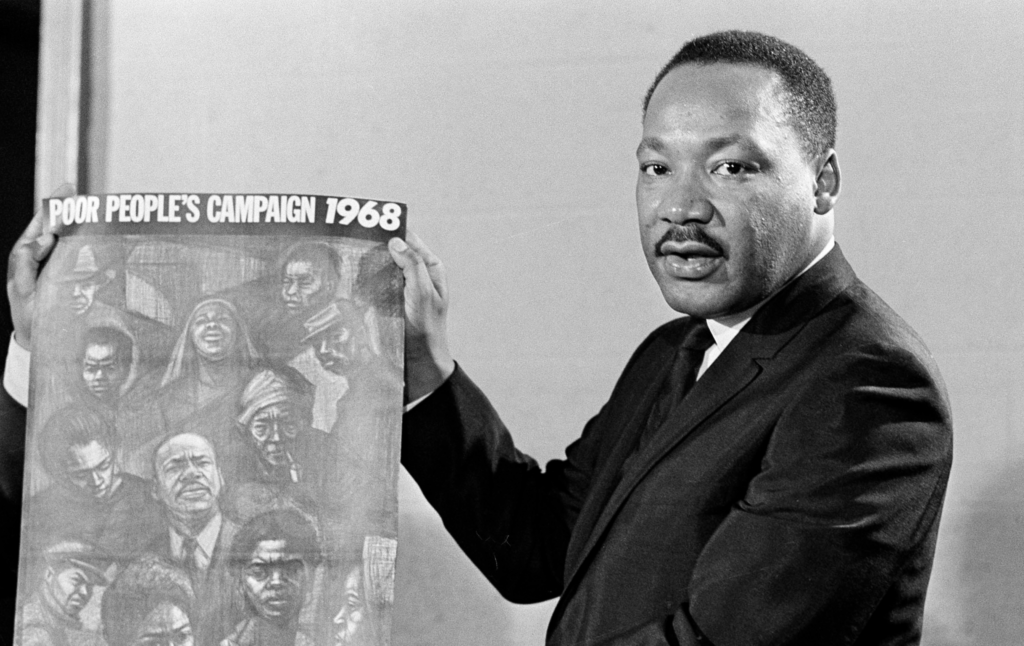

On this King Day, remember the radical King, the man who spent his final days in Memphis supporting striking sanitation workers as part of the Poor People’s Campaign for economic justice. Remember the “Drum Major” King and the “Beyond Vietnam” King who inspires us to create a more humane and just society by focusing on the needs of the poor and marginalized. Remember the King who focused on structural causes of injustice, on the exploitation of workers in a capitalist economy, and who connected our deeds at home to our wars abroad. And remember the mass movements of people that King was part of.

As Fleming points out, as much as Coretta wanted to emphasize the importance of King’s nonviolence, the U.S. remains an incredibly violent country. The violence of mass shootings, the violence of militarism which kills people abroad and scars the lives of military personnel, the violence of police brutality, the violence of an economy that works for the rich but not the majority of average people, the violence of a for-profit healthcare system that lets people die if they can’t afford treatment—all of these are injustices that King would have wanted us to protest and fight against.

Remember that individual acts of service are good, but we need to create mass movements and engage in civil disobedience in order to win large-scale policy changes to build a world in which every person can thrive. Remember that the struggle to create a world based not on consumption, militarism, and racism—but on love, compassion, and human uplift—is our work today and every day.

-

Although ‘communism’ is a dirty word in mainstream U.S. political vernacular, it’s worth noting why it was that a civil rights activist like King would be called a communist. As Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor has written, the dire conditions facing African Americans in the mid-20th century led many of them to revolutionary conclusions. Many civil rights activists were communists. And the Communist Party actually had actually taken up the race issue decades before the civil rights movement. As explained by Robin D.G. Kelley in Hammer and Hoe: Alabama Communists During the Great Depression, “In 1928, the communist position internationally was that African-Americans in the South have the right to self-determination. Meaning: they have the right to create their own nation in the South. In this position that came out of Moscow, it came from other black communists around the globe. And with that idea in mind, they sent two organizers to Alabama and they went to Birmingham. And they chose Birmingham because it was probably the most industrialized city in the South.” The Party organized Black sharecroppers and tenant farmers to challenge their oppressive working conditions and to obtain government relief from unemployment during the Depression. So when somebody smears racial justice activists as ‘communists,’ that actually tells you something about what communists have stood for and suggests that the name-caller themselves doesn’t stand for racial justice. ↩

-

Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor has also written about how Barack Obama scolded Black people for their personal behaviors. ↩

-

Here, King notes that he once asked white jail wardens in Birmingham what they were paid, and when they responded, he told them, “You ought to be marching with us! You’re just as poor as Negroes!” He then goes on to explain how white people are kept poor because they have the wage of racial superiority. The implication, of course, is that racial solidarity could win better wages for everyone. ↩