A Philosopher Explains Why It’s Rational to Be Angry ❧ Current Affairs

Is anger the enemy of cool reason? Or can it be an important and rational part of our political commitment?

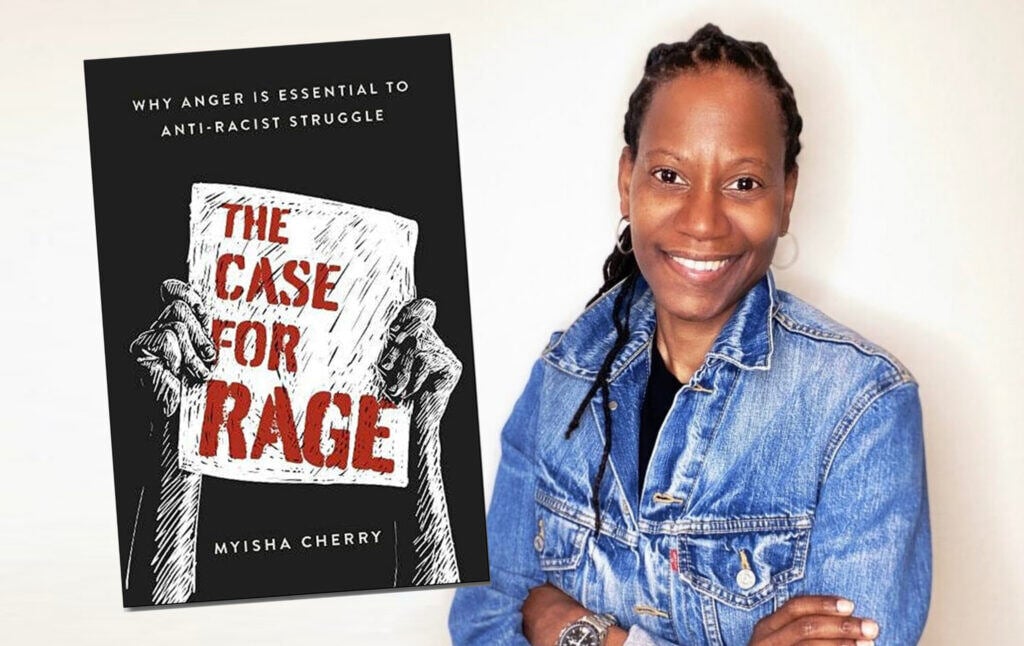

Myisha Cherry is a philosopher at UC-Riverside whose book The Case for Rage: Why Anger Is Essential to Anti-Racist Struggle (Oxford University Press) argues that reason and emotion are not, as many people assume, opposites, but that our emotions are often important expressions of our reason. We get angry when our implicit framework for how the world ought to operate is violated, and Prof. Cherry argues that it’s okay and even important to have this feeling. She shows that in the history of social movements, anger has been an important motivating factor, and she argues that it can coexist with love, compassion, and thoughtfulness.

Cherry does not advocate “mindless” rage. She says we need to be reflective and figure out whether our anger is actually well-grounded in facts and sound morality. She distinguishes between different types of anger, some of which are healthier and more factually grounded than others. But she believes that if we embrace the right kinds of rage, they can help us “build a better world.”

Nathan J. Robinson

In the way we talk about it casually, anger is often treated as something inherently bad. Being angry is something you want to avoid. With a piece of writing, someone might say, “it’s a very angry polemic,” as if it’s just wrong to be angry. But you make the case for rage, and I like this because I feel angry about a lot of things a lot of the time. I want to feel justified in that anger. So, tell us, why is it okay to be angry?

Prof. Myisha Cherry

Before I answer that question, I think we should be sympathetic to those who are perhaps critical. And so, when I think about why people think that anger is bad, I think it’s for several reasons. In one sense, we have a tendency to think that things that feel bad are actually bad. It doesn’t feel good to be angry. It feels good to be joyful. It feels good to be compassionate. It feels good to be happy. And so, we’re resistant to anything that doesn’t feel good. But also, we have a tendency to think that when anyone is angry, then we’re totally in an out of control state. Now, there are some people who can’t control their anger, but I don’t think that’s the case for everybody. Also, I think that we have a tendency to think that anger always comes with this desire to engage in some kind of vengeful behavior, and I think a lot of us are against revenge. And so, of course, we would be against anger. When I think about those three reasons, I’m sympathetic to them, but I disagree with them all.

I’m of the view that using what feels good as a gauge for what is actually good for us isn’t a good thing, because sometimes something that is painful can point us towards a kind of transformation. Like if I’m hungry, that hunger pain doesn’t feel good, but it’s trying to tell me that I need to eat nutrients. So, I think that’s just the wrong proxy. I also think that even though anger doesn’t feel good all the time, I want to say that it is good for us, and it’s good for us in a variety of ways. It’s good for us because it points us towards a wrongdoing that has occurred. If we want to live in a just and ethical society, this is very important as a kind of corrective. So, one of the things that anger does, and one of the reasons why I don’t think that it’s bad, is that it points us towards the bad so that we can change it. Not only does it let us know that something wrong is happening, but with that, we can go to the wrongdoer and challenge them to be better.

I grew up in a single parent household. Sometimes my mother’s smile made me a better child. But that anger—when I knew that she was serious, concerned about my moral well-being, and really pointed out my wrongdoing—that really motivated me to want to be a better person. And so, for people who are angry, the whole objective is to allow us to stop doing the bad, and help us transform it to become better. That’s why I think that we shouldn’t get rid of it, that it’s not necessarily bad; it points us towards the bad so that we can morally transform.

Robinson

Your book is about antiracism and the antiracist struggle in particular. So, when we see hideous racist violence, for instance, my first reaction is, how could you not be angry? What I like is that you don’t just say that anger is acceptable, or that we should understand or empathize with anger, but that anger is essential. And I do feel like it’s bizarre not to be angered by certain things. It feels like anger is the appropriate reaction, and to not be angry feels almost like minimizing the significance of injustice.

Cherry

I think that’s right. I want to break down that statement into two domains. So, when I say that it’s essential to antiracist struggle, the question is, who is the “who” in antiracist struggle? When we think about societal transformation, particularly in the American context, a lot of our transformation has come because people organized in groups and protested and challenged the powers that be. And I want to say that a lot of that organizing was because people were angry; that mobilization that was spawned by anger was the thing that allowed certain kinds of things to be passed and things to be better from a societal issue. Now, it’s not to say that everybody during that time period was that angry. I want to be sympathetic here—as you can see, sympathy is my thing—since for a lot of people, their default reaction to a bunch of stuff could be compassion, and I don’t want to minimize that. For me, I just have a kind of disposition in which anger is usually my first response. I want to basically say that because there are various roles for us to play, there are a bunch of people who can get angry and can use that to bring about change, and there are other people who don’t really have a disposition to be angry and will use their compassion to do different work, but it’s all leading to the same thing. I want to make room for the individual and the different individual kinds of dispositions. But historically, when we think about social mobilization, that has come about because people were indeed angry. That’s just a historical point. I do question those individually who see an injustice and are not angry, but I think I’m more questioning of indifference. I’m more questioning about other kinds of emotional responses that they had which show an ignorance or a kind of indifference to what’s happening. But I want to make space for a variety of emotional responses.

Robinson

That’s fair.

Cherry

Anger. Anger is the thing. When we think historically, it does mobilize us.

Robinson

I guess when you look back at the rhetoric of the abolitionists or those who went after child labor, they saw the situation around them, and it upset them deeply. They felt emotions that we feel when we look back. Emotions are often seen as irrational things, but we feel like the emotions they felt were the rational reaction, and those who were indifferent are the ones who didn’t have the reaction that we would today consider rational.

Cherry

I think that’s right. It goes back to my point about emotional diversity. If a person doesn’t have a disposition to be angry—I don’t want to over-criticize, but I do want to know what they feel. I think what a person feels reveals a lot about what they value. And so, if compassion is still fitting when it comes to injustice, just as anger is, indifference is not rational when it comes to injustice, as well as a whole bunch of other kinds of emotions. For many people, when they see angry people in the streets, they get angry at their anger. So, that’s not a rational response to what’s happening. But what is strange is that it’s the angry protesters and organizers that get depicted as the ones that are out of their minds and irrational, that need to calm down, when it’s the complete opposite.

Robinson

I think it’s interesting that philosophy is often considered this kind of loveless, emotionless field. Certainly, when I took philosophy classes in college, that was one of the things that kind of irritated me. We discussed in our political philosophy class all these theories of government—these kinds of abstract theories of the relationship of the individual to the state. And I, as someone who feels like the issues that we talk about are real and affect real people, found that kind of absence of emotion in philosophizing to be odd. So, I like that what you do is you bring emotion into philosophy and say it has a legitimate place there.

Cherry

I want to trouble even the veneer of “it’s all abstract, with no emotion.” That’s not what humans do. And so, even when I think about the history of philosophy, and about the Rousseaus and the Kants, and even about the Socrates, I’m less hesitant to think that there wasn’t an emotional kind of motivation. If you think about Socrates, Socrates was a very angry man—angry about these ignorant people who thought they knew what they knew, but didn’t know. So, I think if you are a human being, and I think even if you are engaged in what we consider a rational enterprise, that is not absent of emotion. We have a tendency to think about governance and about people who are in any kind of government position—and particularly, we have an image in mind of the white male who’s in governance positions—as rationally making these decisions without being moved by any kind of emotions. I think that’s ridiculous. I think that’s a falsity. I’m just trying to illuminate that as human beings, what makes us distinct is our rational capacity, but also our emotional capacity and our capacity to understand that emotion. Those emotions arise due to rational reasons, and to use those emotions to engage in collaborative and transformative exercises is part of the human ability that we have. And so, when we deny ourselves that kind of emotional capacity or emotional feeling, we’re denying ourselves, in a sense, a unique part of what we take to be human.

Robinson

I guess we can pretend that we are cerebral and purely rational, but we all have to interrogate what we’re really feeling and how it’s motivating what we consider to be rational—there might be something deeper there. I suppose I should have asked this earlier on because we ought to talk about what we’re talking about: what is anger? What do you mean by anger?

Cherry

We’re talking about emotion; if we want to really get meta, we can talk about what an emotion is, but let me just say this. Usually, the fingerprint of any emotion that will help us understand what that emotion is, will always have some kind of physiological component to it. So, when I’m angry, there’s this traditional kind of physiological response that someone gets red in the face. In the African American community, we use this notion of “heated”: our body temperature rises, we may even shake a little bit. We do feel this inside of us, and that’s a very different feeling than the happiness feeling. It has this kind of unique physiological component to it. But also it arises as a result of what we consider a wrongdoing. And it’s very different from happiness—happiness doesn’t arise due to a wrongdoing. It arises as a result of a happy happening or event. And sadness doesn’t arise because of wrongdoing. It arises because of loss, etc. So it’s always targeted to that particular thing.

And also, when we think about an emotional profile, typically it’s the case that emotions are going to move us in some kind of way and motivate us to do a certain kind of thing. And whether we do that thing is a whole other thing. Fear, for example, typically motivates us to flee. But what anger does is motivate us to approach the target of whatever is causing us to be angry. So typically, when you’re angry, you’re not running away, but instead running towards the thing that’s making you angry. And so, those are the three important aspects of the anger profile: it’s directed towards wrongdoing, it motivates us to approach the target of the wrongdoing, and it has a unique physiological response. And that’s what we typically take to be anger. And as much as I’ve said something about the target of anger being wrongdoing, usually, when anger arises, it involves some kind of judgment—that what has occurred is a particular wrongdoing. And this goes back to our rational point earlier, that for many people they think that when you’re emotional, it’s absent of any kind of rationality. No. I think I’m a cognitivist in this sense. There’s no way that I can be angry unless I have rationally judged that a situation has occurred that is indeed wrong. So, it does involve more wrongdoing and more judgment. In that sense, anger is very much rational.

Robinson

That’s totally fascinating, and you’re right. As I think about what makes people angry, there’s always an implicit idea that something shouldn’t have happened, that it’s wrong. Obviously, there are plenty of people who get angry for reasons that we think are unjustifiable, but they have, internally, some sense that they have been wronged and this shouldn’t happen. There are some internally constructed views of the things that are okay to happen and what’s outrageous to do to me.

Cherry

And that’s a very rational enterprise. That’s something, in some ways, a baby can’t do because it just doesn’t have that kind of complex, rational capacity yet. I’m hesitant to think that about my dog—I don’t know, I’m not going to rule that out. But it’s a high kind of cognitive exercise to do that. And so, yes, you could be wrong in that judgment, just like we’re wrong about a bunch of things that we think we are right about. But that’s still not to say that the anger doesn’t arise as a result of some kind of rational exercise.

Robinson

Give me a real world example to kind of illustrate how there’s an implicit code of what should happen here.

Cherry

So, I always tell folks that there’s nothing wrong with anger, that anger points us to a wrongdoing in the world, but you could still be wrong. This is one of the things that I wrote about in the first chapter of the book. There are a variety of angers that can arise in the context of injustice, and the example that I use—a particularly political example, and I want to be very careful with this—is January 6 and the storming of the Capitol.

Robinson

Very angry people.

Cherry

Very angry people. A lot of them thought they were right in their anger, but the question was, was it fitting? Even though it may have arisen as a result of some kind of cognitive exercise, was the anger fitting? That is to say, what they took to be the cause and the wrongdoing, did that actually occur? Was the election unfair? Did Biden steal the election from Trump? When we look at the facts, that’s not the case. So yes, they were angry, and that came about through a rational cognitive exercise. But their anger was not fitting because the facts did not match what they thought to be the consideration.

Here’s the interesting thing sometimes about anger: we have a tendency to beat up those protesters, but we have a tendency to do the same thing in our ordinary lives. So, what happens when we are resistant to the evidence to suggest that we’re wrong about what we think is right? What are the psychological things that happen when we try to be right in our anger when all evidence is to the contrary? I see that with what happened on January 6 and with conspiracy theories, etc., but we also see that in our own interpersonal lives. We hate to be wrong; we think that we’re always right. And so, I think that’s a challenge for all of us. So yes, your anger could be rational, but it doesn’t mean that it’s fitting, and it doesn’t mean it’s right. You could be wrong about the state of affairs.

Robinson

With January 6, it’s crossed my mind before that if you believed that the election was stolen, that would be a pretty fair response. What would you do if you thought the election had been stolen? If you thought that one of the candidates had manipulated their way into office, it would make sense: we’re going to go to Washington, storm the Capitol, and demand a fair election. Because they were all lied to by the president of the United States, some of them thought they were demanding democracy and fairness.

Cherry

Yes, they were true patriots in that regard. But they were wrong.

Robinson

Right. But, we wouldn’t judge them on their anger.

Cherry

Yes, exactly. And so, when I was editing the book as I was witnessing those events, I thought, but they’re wrong, it’s not fitting. I’m writing a book on anger, I see these angry people, but please listen to the evidence. Because what is fascinating about anger is that it can motivate us to do the kinds of things that those individuals did at the Capitol. So, like I said before, it gives you this feeling and involves this judgment, but it does motivate you to approach the target of your anger. And I mentioned earlier about how social movements, because of angry people, have led to social transformation. So, anger has this kind of motivational thing to get us going about a corrective, but things can go awry. What went wrong? We can undo the very rightness, the very justice, that we’re after. And so, I think it’s very important that as much as this feeling is important, we have to also be what I call epistemically responsible and make sure that we’re right about the state of affairs.

Robinson

Yes. You make the case for race, but it is not the case for all circumstances. We know that some of the worst and most horrendous movements of people, such as the October 7 attacks, can be attributed to anger as a result of the conditions in Gaza. And then the response was an act of vengeance out of anger. And we see a lot of horrific human carnage now coming in part from the fact that there was a motivation of anger in response to a perceived injustice.

Cherry

Right. I’ve been very quiet online recently. I talk about anger and also about forgiveness. I think right now, many people are angry, and they feel justified in their anger. I think when you have opposing sides to any kind of issue, the epistemic responsibility thing that we were talking about earlier becomes harder. And this goes back to one of the things I think is important here: if our anger is supposed to lead us to just aims, I warned about making sure that we’re right about things so that our anger won’t undo the very thing that we’re after.

What do we do in these moments in which there are conspiracy theories and fake news? Or when there’s no evidence, or only some evidence? We rely on news entities and leaders to tell us the truth. What do we do at this moment? What is the responsibility that we have as citizens of the world to make sure that our anger is responding to things that actually occurred, in ways that are more epistemically responsible? So, if there’s anything I want to say about this moment, it’s that I understand why people feel the way that they feel. But the challenge for us all is how to make sure we’re right in feeling what we feel. What are the kinds of epistemic responsibilities that we need to take to make sure that we have the right information about these particular things? I don’t have the answer to that. It’s a challenge for us all.

Robinson

It strikes me that the kind of righteous anger that is directed towards getting rid of something bad and unjust is that we want the anger to achieve its own abolition. Because as you say, anger is not something we want to feel, or that we enjoy feeling, and it’s in response to something that we think is wrong. We’re ultimately trying to change the situation. What is the process by which anger dissipates? You mentioned forgiveness. If we take anger as legitimate and justified in certain situations, how do we ideally get past our anger to the post-anger stage, which is presumably what we’re ultimately intending to do?

Cherry

There are two ways to answer this question, given everything that you said. The first is the easiest way for me to answer the question, and it’s something that I addressed in the concluding chapter of my book. People sometimes ask the question, particularly for a lot of protesters: when are you going to let go of this anger? I’m thinking about this in an antiracist context. The anger is going to dissipate when the racism dissipates; when the discrimination goes away, and police brutality based on race goes away, and the white supremacist violence goes away. Now, when is that going to happen? I don’t know. But we would say each time a kind of wrongdoing occurs, when racial wrongdoing occurs, that anger will be fitting. It may just be the case that anger doesn’t ever go away as long as there’s an injustice in that particular respect.

Now, I want to address something earlier that you said because what I’ve been talking about, and what I’ve been assuming both of us are thinking about, is thinking about the virtuous kind of anger that motivated the book. That is, the kind of anger in which you are angry at actual wrongdoing. And it’s a wrongdoing in the sense that it is a wrongdoing, by the very objective nature of what we take to be morality. So it’s not that “Jews are replacing me,” and I think that’s the wrongdoing. I’m talking about actual wrongdoing in which people are being oppressed, marginalized, or beaten because of their race or gender, etc. But there’s a lot of people whose wrongdoing is not that—it’s the complete opposite. And so, for them, their anger is not going to dissipate until a particular group is eradicated. So, I want to be very careful in answering your question about, when is it going to go away? I don’t know when this is going to go away. It’s not going to go away until the very thing that they’re angry about goes away. I want to be very careful that the kind of anger that I’m particularly talking about is the kind of virtuous anger that is right and fitting, that is about true justice, and not for what I’ve been referring to as having racist, white supremacist aims, etc.

Robinson

Yes. You’re a philosopher, and we should be clear that in the book, what you do is go through and create a kind of typology of different types of anger. You think about and draw out careful distinctions. This isn’t in your book, but tell us about the good anger versus the bad anger.

Cherry

A while ago, I laid out what I take an emotion to be and how anger is a distinct emotion. And so, I’m going to do some other distinctions as you just pointed to. There’s a variety of angers that we can have in a political context, and I give names to them, but I think more importantly, it’s interesting for me to lay out what I think is the difference between them all. When I think about anger, it’s going to have a target. So, what is your anger about? It could be about racial discrimination. Also, what is the anger motivating you to do? It could be why I want to protest racial injustice so that it can be eradicated. And then there’s also a perspective that informs it. So, what is the kind of thinking of an angry person, and what’s guiding their motivations? I think that people should be respected because they are human beings in their own dignity, and so we need to make sure that they live in a world in which they’re safe and treated with respect. I call that anger Lordean rage. It’s directed towards change. The perspective that informs it is a perspective that’s very interested in making sure that we get justice for everyone. It motivates a kind of change and radical transformation in society so that people can be respected and treated with dignity.

But there are other kinds of angers. So, I mentioned the Capitol siege. When I think about it, it’s an example of a kind of anger I call rogue rage, or more appropriately, wipe rage. And so, this kind of anger, who is it targeted at? Well, it’s targeted at scapegoats. It’s targeted at immigrants. An example of this will be when someone asks why they are economically disenfranchised in their community and—this goes back to the epistemic responsibility point—in trying to figure out why there are no jobs, they basically say it’s immigrants or working-class Black people who’ve taken all the jobs. And so, it’s targeted at a scapegoat. So, what is your motivation, and what are you aiming for with this particular anger? Usually, in what I call wipe rage, you want to eliminate the people that you’re angry with. What is the perspective that’s influenced it? You have a zero-sum game of thinking about the world. If you don’t win, or other people are winning, you think that you’re losing. And so, if you think about that profile, that anger is going to look very different in the world, and it will do and motivate us to do very different things. I want to motivate people to have a more virtuous kind of anger, and a lot of work has to be done to get someone who has wipe rage to get them to have a different kind of virtuous rage.

But not all rage is created equally, and we can figure that out by asking them, who are you angry with? What is the kind of thinking informing that anger? What are you aiming to do? I think that will answer a lot of questions as to whether the anger is indeed good, or if it’s “bad.”

Robinson

What you’re saying there raises the point that anger can be made consistent with feelings of empathy, solidarity, and love. I was struck recently by how Cornel West talks about love a lot. He says, justice is what love looks like in public. He just gave a speech about the bombing of Gaza where he was deeply, deeply angry. His philosophy is often built around love, but also, you can have the anger. So, can you talk about how we can reconcile the seeming antithesis between a person who is motivated by love and anger? Can we be both?

Cherry

I believe so. I don’t only believe it. When you look at people like Martin Luther King Jr., Sojourner Truth, James Baldwin, and Cornel West, you see evidence of this kind of thing. And I think this is just one of the things I think people are critical of. They’re critical of anger because they think if you’re angry, there’s no way that you could feel loving or have love or have compassion in your heart, and that’s not necessarily the case. In other words, in the book, I basically write that not only are these emotions compatible, often it’s the case that anger is an expression of love.

So, I mentioned an example earlier of my mother being angry at me because I did something bad. If you love and wish the best for your child, then when your child messes up, you expect loving parents to be angry about that. And so, her anger and disappointment at me was an expression of that particular love. And we could talk about this in the societal sense.

When you think about James Baldwin’s writings being angry, he basically says, I’m angry at America because I love her so much. And so that’s why, in his words, I insist on perpetually criticizing her. So, the two are compatible. You can be angry at, and on behalf of, someone that you love. We’ve been talking about indifference—if you love me, and you see me being abused, I expect some kind of anger. Because if you’re my friend, and you’re not angry, I’m really going to doubt how much you love me. That’s how intertwined these two things are. Love and anger are compatible, and it’s also compatible with being compassionate. For a lot of people who engage in social movements all day, every day, anger is not the only thing motivating that. It’s not going to sustain you in that way. It’s because you love oppressed people. It’s because you love justice. And so the two are compatible in expression of each other.

Robinson

It’s strange how obvious that is. It’s so obvious in your personal life, that you can be angry at someone you love. But for some reason, we have this idea that with protests there is an opposition between anger and feelings of love and generosity.

Cherry

And to be clear—I think you’re being sympathetic that it’s an epistemic kind of failure—but I think a lot of times it’s used as a tool to silence and control people. It suggests that your anger is not patriotic—your angry protests don’t show a love for America—and people do that in order to kind of silence people. So, I want to be cognizant that sometimes a lot of that critique is a way to police and silence protesters.

Robinson

Yes. And not just in protests. As you pointed out, there are all these kinds of social rules for who’s allowed to be angry and when.

Cherry

It’s interesting that you mentioned how rationality is very much connected to emotions, but also, control, order, and social power are connected to emotions in a society in which we’re not all equals in practice. In a society that’s full of social control, one of the most powerful ways that you can control people is to control how and what they feel.

So, I talked about policing and silencing earlier. Let’s talk about gender. It used to be the case that women were not allowed to be angry; only a man could be angry on her behalf. And the only reason why that was allowed is that a woman had no value within herself. Value is very much connected to anger, but if you don’t have any value, then when you’re mistreated, you have no right to speak out. But a man could be angry on her behalf because a woman was his property. By virtue of his gender, he was already valuable in society, and when that property was infringed upon or disrespected, then he was disrespected. So, his anger was respected. Anger has always been connected with power and value, and you can always tell if someone values you as a member of society by the way in which they respond to your anger. I think it’s important for us to be very cognizant of how that happens in the news.

I talked about Martin Luther King Jr.: many times when protest movements happen, I’m always interested to see what political commentator is going to cite Martin Luther King Jr. first, to mention how forgiving and loving he is. That’s a tool used to silence people, and you do that because you want to control them in a certain kind of way. But we think that if people have the right body, they have a right to be angry. So when white men are disrespected, we always think that they have a right to be angry. So, I just want to challenge us in that respect. I don’t think this needs to be said, but all of us have inherent value. All of us have a right to dignity and respect. And so, when we’re mistreated, we have a right to be angry, and we need to be very cognizant and conscious in our individual lives about how we assess and judge the emotions of others, making sure that we do not reinforce and reify power structures and social structures in that domain.

Robinson

It seems like a kind of trivial or very frivolous example, but in your book you cite the wonderful SNL skit with Idris Elba, who plays a Black man who turns into an indignant white lady when he’s angry. It’s a superpower.

Cherry

For those who have no idea what we’re talking about, please go on YouTube and find it. I think it’s a wonderful example of whose anger we take seriously in society. People are familiar with the Incredible Hulk stories. So, instead of Idris Elba turning into the Hulk, he turns into a white woman—what we consider a Karen. And mind you, the context is when he’s angry, no one takes him seriously as a Black man, but his anger allows him to transform into a white woman, and when she’s angry, everyone takes her seriously. So, I find it fascinating because of what it shows us, even though they’re two different genders. If they were both white individuals, then I think it’ll be the opposite, like a woman will transform into a white man. But I think what I find fascinating about the skit is that they’re showing us that the gender falls apart in some ways, or instead, it operates differently. In the racial context, his anger as a Black person is not respected, but it is respected when he’s a white woman. And so, I think we need to be very careful in making sure we don’t reinforce these structures in the way in which we assess and listen to people’s anger, just as we don’t want politicians or people in power to do the same.

Robinson

Back to where you started, you discussed how in the discourse there is this idea that anger and rationality are opposites. And you quote one of the leading political philosophers of our time, Martha Nussbaum. She has a few reasons why she argues against the political uses of anger:

“It downgrades the wrongdoer to a moral position beneath us, creates a desire for payback and revenge. Just as it can be useful, the abuses are limited and goes astray. And it’s an impediment to the other emotions that we need, generosity, empathy, and love.”

And so her ultimate conclusion is that it’s a bad strategy and a fatally flawed response. You’ve addressed somewhat of why you think that’s wrong, but what are the consequences of adopting that view? If you adopt that view, what are the political consequences in terms of the things you’ll allow? Where does that view take us?

Cherry

It doesn’t get us to the transformations that we’ve talked about so far. It doesn’t really hint at the historical record about how there were angry people who responded to injustice, and how that anger motivated them to engage in social transformation. We are reaping the benefits of their anger today. As far as that utility and its limits, for me as a Black person in America who has so many more rights because there were people who were angry on my behalf in the 1800s and 1900s, to say that their anger has limits just doesn’t match up to the actual record. And this also gives me an opportunity to reiterate some of the things that we talked about, about how these things are not an opposite. Generosity and love are not incompatible with anger. You have anger because you love people, because you are expressing compassion. And you don’t just have anger all day; we’re not always constantly in an angry state all day. But also, it’s not backward looking. It takes us towards the future. It takes us to a better world. It doesn’t try to bring the wrongdoer down; it reminds the wrongdoer that you’re not above me, that we’re equals, and so treat me accordingly.

And so, as much as Martha Nussbaum is a brilliant philosopher, we do disagree in this particular regard. And we disagree because I truly believe when I think about the historical record and my interpretations of not just the work of King, but a whole bunch of other folks, I know that I am the recipient of the work and the sacrifice of the angry people, but also angry people who were angry because they love folk and were compassionate towards folk. And I see not only did that happen in the past, but that’s happened in the present. We think about Black Lives Matter. We are a recipient of the work of angry folk. I think arguments like that have made people feel not seen, has made them feel guilty about their true feelings, and it makes them repress and suppress their emotions. When you have a situation like that, where you’re repressing and suppressing, that’s gaslighting people and putting them in a psychological state that’s not healthy for them. And so, I want to recommend to people, if you’re angry about injustice, you’re not wrong. You’re not a hindrance to democracy. Your anger shows that you value lives. I want you to use that anger in socially transformative ways, and there’s nothing wrong with it. Get with other people who are doing it to make a change, and with all that together, we can create a better world.

Robinson

You have the wonderful title of your essay for The Atlantic, “Anger Can Build a Better World.” In the book, you discuss how we need to manage our anger, make sure it is directed towards actions that achieve our goals that take away the thing that is creating our anger, rather than just revenge. So, we have to take our anger and use it productively. You make a pretty compelling case here that it can, in fact, be used productively.

Cherry

It can. There’s work we’ve got to do. I don’t want to act like anger is this mythical god that’s doing all this stuff. We have agency as human beings and in those things that we have to do. And so, I’m challenging people that anger is never an excuse not to be responsible and rational. But there are things that we can do. We can hold each other accountable. We can get with people who are using their anger in positive ways. And as long as we’re checking ourselves, and making sure that our anger stays productive, stays motivational, stays towards making sure that we dignify folks, then we’re on the right path.

Transcript edited by Patrick Farnsworth.