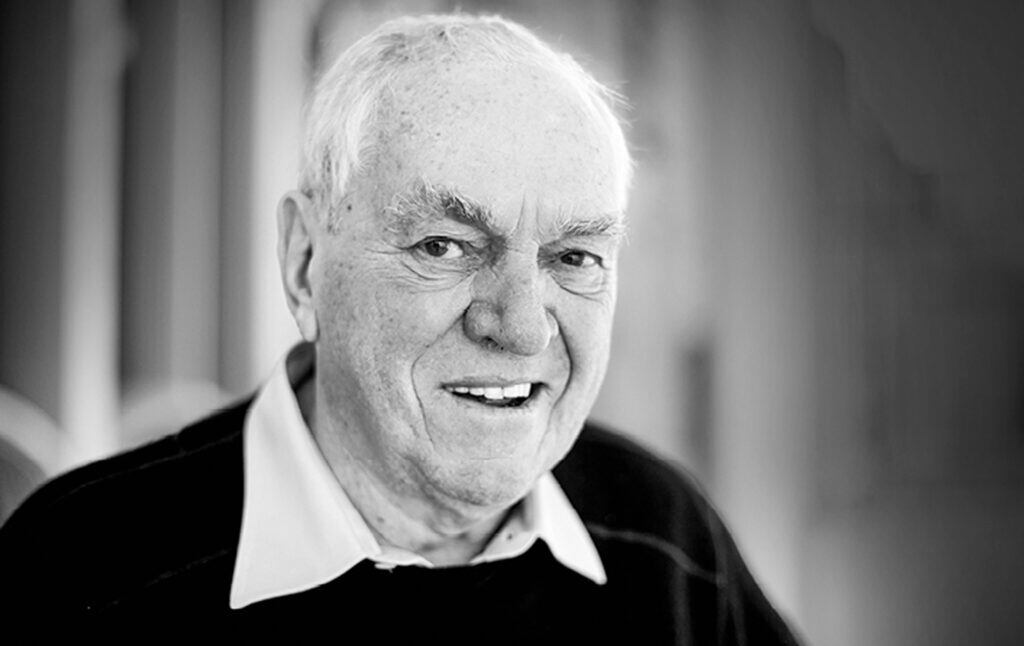

A Final Conversation With Ed Broadbent on the Continuing Struggle for Democratic Socialism

Perhaps the best known democratic socialist in Canada, the late Ed Broadbent discussed what he learned working in government coalitions and explained that the struggle for democratic socialism is a constant one.

Ed Broadbent, who recently passed away, was perhaps the best-known democratic socialist in Canada. He served for 14 years as the head of the country’s New Democratic Party, after beginning his career as a political theorist. Broadbent’s book, Seeking Social Democracy: Seven Decades in the Fight for Equality (written in collaboration with, among others, Current Affairs contributor Luke Savage), is a tour through the last half century of Canadian politics, and for Americans it offers a fascinating window into what it looks like when a democratic socialist politician gets close enough to power to have to make serious policy decisions. Shortly before his death, Broadbent came on the Current Affairs podcast to introduce listeners to the basics of the Canadian political system and talk about what he learned over the course of his career, where he earned the respect of a wide swath of Canadians, to the point where he has been called “Canada’s most iconic social democrat” and “the best prime minister we never had.” We discussed how Canada built social democratic institutions and how to have a politics critical of both state and corporate power.

Nathan J. Robinson

Because we have an American audience, we might want to start with a lay of the land for Canadian politics. So, for those who don’t know the status of the New Democratic Party [NDP] within the system, could you explain to us what the basic factional alignments are and where you fit within it?

Ed Broadbent

You have to start with the structure of a parliamentary democracy like ours, as opposed to a presidential system like yours. Ours depends, in terms of the selection of the Prime Minister, on the number of seats he or she obtains in the House of Commons. And if you don’t get enough seats as a majority plus one, then you have to work out an arrangement with another party.

Historically, in Canada, for the past six or seven decades, that has meant the larger party—Liberal or Conservative in Canada—has had to work with a smaller party, namely, the New Democratic Party of Canada, for most of that period. The consequence is that we as a party—and this is going on as you and I are having a conversation right now—constitute a sufficient number of seats to give the Liberal Party of Prime Minister Trudeau a governing majority.

And for that—and this is the social democratic element and impact—the Liberals have to do certain things. Again, as we speak, they’re introducing, piecemeal, a universal dental care program to see that every child in Canada has virtually free dental services. This is a consequence of a deal worked out between the New Democratic Party—my party—and the Liberals. The Liberals want to do it to stay in power; they’ll get our votes as long as they do this. This is a shortened version, and I could go on some length. There are a series of social democratic measures over time—universal health care, universal pensions, a PharmaCare program—that the New Democratic Party has been able to extract from a larger party as a condition for our votes in the House of Commons.

Robinson

So, you as the social democrats and socialists in Canada don’t get to rule, but you do get to extract, as you say, concessions. And I assume this involves a lot of very difficult and complicated negotiations and figuring out how to use your power, when to withhold the power that you have, and what you’re going to expend it on. They need you, but also they can defy you. How does this work? Tell us a little more about it.

Broadbent

Yes. That’s why in the present circumstances, for example, there’s a three-year agreement signed publicly by the leaders of both parties, an official public commitment to the maintaining of the Liberals in power on the condition they meet certain social—especially social—policy requirements, but also action on the environment. I should mention this is equally important with the present government.

Robinson

It sounds as if oftentimes, the Liberals are not going to do the right thing unless they’re forced to.

Broadbent

That’s to put it euphemistically, yes. The father of the present prime minister, Pierre Elliott Trudeau—a man that I dealt with virtually throughout my political life—did say to me in private one time that he liked having the New Democratic Party around because he could always threaten the more right-wing members of his caucus that if they didn’t comply with certain social policy initiatives, they would lose the support in the country to the NDP and not form a government. And if there’s anything Liberals dislike more than injustice, it’s having themselves rejected from power.

Robinson

He kind of suggested ‘we like having you because you make it easier to do the thing that we actually want to do.’ And then I seem to recall in the book that you have a kind of skepticism of this, which is the same skepticism that Luke Savage—who collaborated with you on this book—and I had when wrote about in Current Affairs about Barack Obama. We analyzed the question: what does he really want to do? And to find that out, you then ask: well, what does he do when he is not constrained? That will show you his true beliefs. And I seem to recall a comment you have in here, I’m not quite sure I believe that he wanted to implement our agenda and was satisfied when we made him do it.

Broadbent

That’s true. I had that skepticism. But generally, in political life, I figured it was a mug’s game to try to guess the motives of your political opponents. All politicians, by definition and on some level, are self-interested, or they would not be in politics. And so, the key thing for me is to watch what people do and not what they say. That’s the real stuff. That was a good relationship we had with Pierre Elliott Trudeau. One could see explicitly what he did and what he didn’t do.

Robinson

Going back to your time as party leader, could you tell us more about what your social democratic agenda was and provide an example of how you managed to use the leverage that you had to alter government policy without being in an ultimate position of power?

Broadbent

One clear example that came was during the energy crisis in the early 1970s. There was a discussion in principle of whether the state—some government agency—would own all or part of our petroleum industry. The Liberals had come up with a plan that intimated they would be interested in creating what we call the Crown corporation, which is the big state enterprise, but they hadn’t done it. At this particular time, I was chair of the New Democratic Party caucus—not the leader, but the chair of the caucus.

On the instructions of the caucus as a whole, I went to a senior minister, Mr. Trudeau, in the early days of 1971, I think—just before the Christmas break. I said to this minister, politely but clearly, that if they didn’t announce and take steps to fulfill the announcement of the creation of Petro-Canada—a state enterprise in the oil industry—before Christmas, we would vote to bring the government down and there would be a general election. That was an explicit commitment, if you like, I made on behalf of my caucus, and it was clearly understood by the Liberal minister. And within a matter of days, they did announce the creation of Petro-Canada, which in its early years turned out to be a very large and, on the whole, successful public enterprise. That’s one of the clear examples people could see upfront about what was happening.

Robinson

What’s interesting is, in your book, you write how the creation of Petro-Canada represented a union of hard-headed practical politics and social democratic philosophy. I want to discuss practical politics versus social democratic philosophy because you began as an academic—as a political economist—and then you entered this world of politics where, in addition to ideas and theory, thinking about what justice is, what the good is, and what the arrangement of a decent society is—you have to think about power. I don’t want to misquote you, but you write something like, the number one priority of a party leader, or at least what he has to think about before anything else, is seeking and holding power, because without power, you can’t do anything.

Broadbent

A variation of the question is, when you’re in politics, are you there to sit in seats of power, or are you there to make speeches and influence those who are sitting in seats of power? In Canada, by minority tradition, some people think—largely outside the party—that the role of the New Democratic Party is not to obtain power, but to simply provide ideas and put pressure on one of the larger parties to do things. I don’t share that view, and a majority of the members of my party don’t share that view. And indeed, my predecessors as leader, David Lewis, Tommy Douglas, and J. S. Woodsworth—historic figures in Canadian politics—didn’t go into politics simply to influence others by being brilliant debaters. They were normally the best debaters in the House of Commons, but they went into politics to actually make the political decisions and write the laws, not just to express the values supporting laws.

Perhaps the most significant thing in Canadian social policy was universal Medicare, and that came after a very intense political fight in the province of Saskatchewan, during which time the medical profession went on strike. Eventually, the legislation was passed by a New Democratic Party government, and would not have happened, in my view or the view of most historians, without the NDP—or at that time, it was Co-operative Commonwealth Federation [CCF], a predecessor to the NDP. It was in power at the time, and part of the reason for it being elected to power was its commitment to bring in universal health care. And when they had the power, they did so in a very intense political situation.

Robinson

Well, I’d love to get any advice that you have about how Canadians got their healthcare system for those of us in the United States. Your book is called Seeking Social Democracy. Many of us in the U.S. probably feel that you over in Canada have found social democracy, certainly to a greater extent than we have here. As you say, it was a fight even in Canada. It’s not like it was easy there, either. Looking back on that fight, what are the lessons that you think come out of that, to the extent that Canada has found social democracy? What should we learn from it?

Broadbent

What I learned from it is the experience of our party in the prairies, in Saskatchewan and Manitoba—both of which the NDP has governed—is that it is implemented step by step. There may be at times a sort of revolutionary rhetoric, but the reality is something non-revolutionary. It’s incrementalism, but very successful. Let me illustrate that the CCF came to power in Saskatchewan in 1948, but it didn’t implement the Medicare part of their program until 1961. And the reason, in part, is all kinds of earlier steps had to be taken by that government to build up confidence so that when it took something that was going to be seen to be a profound change in the arrangements of society, at least 50 percent of the society would agree with what they’re doing. I grew up in a different province, but the lesson that I learned from our Saskatchewan success is you must make real promises and then implement them, but do it with the good support of the population. Certain moderation at all times is required, but the moderation does not excuse doing nothing. Moderation can be done by showing respect to the political opposition, but in the final analysis, you must carry out your promise. The promises should be gradual and not revolutionary at the outset.

Robinson

I want to continue on the theme of how to be a pragmatic politician as a socialist. You became quite popular and respected in Canada during your party leadership, with a reputation for being honest and plain-spoken. You mentioned Tommy Douglas, who, as I understand it, is routinely voted one of the greatest, if not the greatest, Canadians of all time. In Canada, you’ve been a socialist politician with some measure of broad popularity and success. And I think in the United States, we who consider ourselves socialists struggle with our marginality, and there’s this conventional wisdom that you have to run to the center if you want to actually win. You didn’t do that. Could you tell us what the secret is to maintaining your socialist principles but also achieving broad popularity or speaking to a broad audience?

Broadbent

Well, I’m tempted to say that I don’t know an answer to that. In my book that came out, summarizing my experience in politics, you’ll find the view that social democracy, in a sense, doesn’t exist. It’s something that’s being constantly pursued by people on the left, and what’s being pursued is to whittle away at the role of the market, and the market’s allocation of so many goods and services. When the market does it, everybody understands it has a high degree of inequality—the rich tend to benefit more from market mechanisms than the average and the poor.

So, a social democratic attitude to this is that we have to get away from too much allocation of goods and services in society on the basis of the market because the average and the poor don’t get a fair share that way. So, to get a fair share, you can either use tax policy to narrow the gap between the rich and the poor, or you can take a certain service out of the market entirely. You have to persuade your fellow citizens that the way of dealing with, for example, healthcare is—instead of a competitive model, which is so wasteful of resources—to bring it all within one framework and remove needless so-called competition. And you can do this with a number of aspects of life, not just medical services, but other social services. It’s a requirement to show the practicality of that, not just the ideological difference between us and the other parties, but that the difference that we are favoring has concrete benefits. And you can show what those benefits are in your argumentation when you’re trying to persuade Canadians to move from the status quo to one of greater social democracy.

Robinson

Certainly, showing that left, social democratic, socialist policies actually help people and convincing them of that seems to be a very important political lesson for those of us on the left. As I say, you started as an academic, as a kind of theorist, and you had to learn to speak to people and convey left ideas in a way that they understood and appreciated. In one part of the book, you write about what you learned from George Orwell and politics in the English language, and you stopped using “working class” because these people don’t really define themselves that way. You started talking about “ordinary Canadians.” It’s an effective language. You don’t change the left ideas, but you think about how to present these ideas in a way where everyone, and not just those who are already grounded in left theory or Marxism, can appreciate what you’re trying to do.

Broadbent

I’m inclined to say to what you’ve just said: yes.

Robinson

Tell us more about how you talk to people about left ideas.

Broadbent

It’s very important how you talk to people. By definition, you’re talking to them as an advocate of a different set of political policies or programs that they understand and you understand. What’s important is that in the context of conveying the message to them, you respect them as human beings; you don’t look down at them as being somehow inferior because they aren’t in agreement with your whole program for the moment. You have to sense, as a fellow human being, that they have a different set of claims in the political process. Theirs are not the same as yours, but you have to respect their right to pursue them. So, in 1968, in my hometown, I went door-to-door to move—I guess I did, though I didn’t know it at the time—a significant plurality of voters to come over to the NDP, and I won by the grand total of 15 votes. That was a very rich learning experience for me, going door-to-door in my hometown and talking to people. To some extent, that played a role in persuading them to switch from conservative bias, if you like, to a social democratic one.

Robinson

How did you convince people to switch?

Broadbent

With a great effort. For example, housing was a big issue in 1968. We had a particular housing program that included public housing and that included fixed rate mortgages at a low level. There was, if I recall correctly, a tuition-free federal university support program to give $1,000 to high school graduates so that they could pick the university that they wanted. At that time, a $1,000 was quite substantial. So, the point I’m making is that, even in 1968, we had a concrete agenda. You could call it socialism, social democracy, or porridge, if you like. The key thing is what it stood for substantively. And what it stood for was a real change in people’s lives.

Robinson

In some ways, you are, in this book, articulating a political tradition—social democracy, socialism, whatever you want to call it—that sadly waned over the course of the ’80s and ’90s with the rise of neoliberalism. You write in the book about how it used to be that when the term “third way” was used, it would be a third way between United States-style free market capitalism and Soviet communism, and there’d be a kind of democratic socialism. In the 1990s, the third way became associated, certainly in the U.S., with Bill Clinton—the third way being neoliberal market fundamentalism with a sprinkling of social democracy, as we might call it. Tell us a little bit more about that old tradition of that third way that you were part of that we need to re-examine and reclaim.

Broadbent

I really like this question because it goes to the heart of political reality today. There were real choices in the 1990s. It didn’t have to go in a neoliberal direction. But Tony Blair and Bill Clinton opted for a more market-driven society than any social democratic leader had ever done, and I think that was a big mistake on their part. It led, in my view, to the Democratic Party’s disenfranchisement of the working class in the U.S., of workers in my kind of hometown, that is to say in cities in Michigan, Ohio, and the so-called Rust Belt. The neoliberal political philosophy created that Rust Belt and helped move capital away from the U.S., largely, but by no means exclusively, to China, withering away a really proud social structure that provided real opportunity for millions of Americans for several decades.

Gerhard Schröder is the other fellow I’m thinking of who was the head of the social democrats in Germany for a while. These political leaders made a big mistake by accepting the Thatcherite model of a small state and big capital. And we in Canada, if I may say so, never fully went in that direction. Both Prime Ministers Mulroney and Chrétien took steps to eliminate parts of the welfare state, but they were only marginally successful in that effort. And one of the reasons, I believe, that that didn’t go further in Canada is the existence of the NDP and our refusal to go in the neoliberal direction. By our refusal to do that, we helped shift the political consensus in Canada in a more progressive direction than that of the United States, for example.

Robinson

There’s a myth or misconception that compromising your values is the pragmatic course rather than staying firm. And it seems that you’re providing an example of how resisting the compromises there that were made elsewhere, was, in fact, actually the pragmatic course for those who held your values and vision for the good society.

Broadbent

That’s true. I believe that to be true. And that’s a theme of the book, and people reading it can make their own judgment and find what’s right about that.

Robinson

Because you mentioned Germany, I just want to bring up Willy Brandt, a figure that comes up repeatedly in your book, who you say is certainly neglected in the United States, but exemplified, for you, this third way—this kind of possibility of a democratic socialism that rejected the bleak authoritarian socialism of the Eastern Bloc, and also the horrendous free market capitalism under which we find ourselves here in the United States today.

Broadbent

That’s right. Willy Brandt was the symbolic figure. After all, he had fled Germany and the Nazis. At the end of the Second World War, he went to Scandinavia to avoid persecution by the Nazis. And so, he had great credibility in Germany after the war for being opposed to everything the Nazis stood for. I got to know him personally, and he was, for me, a shining light of a social democratic personality. He had a great sense of joy for life; life was not something to be endured, it was to be enjoyed, and he embodied that. But he also embodied the program agenda of reducing inequality in Germany. And when he was mayor of Berlin, he had great courage facing the Soviet state.

Michael Harrington didn’t possess power, but he possessed a lot of good ideas. He came from the U.S., and they had an agenda that, as you indicated, was against both Soviet style authoritarianism and total free market capitalism. It was the so-called third way, then, that was sought and was successful for social democrats in what I would regard the real free world (Sweden, Norway, Austria, Netherlands, Canada, and the U.S.). It brought a greater degree of equality. If you look at the Western European countries between 1945 and 1975—and indeed, look at the U.S. and Canada in that period—there’s a decisive move in the direction of social democracy, mitigating the power of the market, and expanding, in a democratic sense, the power of the state.

Robinson

You argue in the book that socialism without democracy is essentially not socialism. And you have this remarkable account of your encounters with Fidel Castro, where you tried to convince him to hold elections, and he just wasn’t interested at all.

Broadbent

That’s absolutely true. And it’s actually very sad because for a while he had legitimate popularity, I would say. For a low-income country, he brought in wonderful medical programs and universal education. But he was absolutely no friend of political and civil rights, and that was a tragedy for Cuba. Even after he’d been in power 10 years, had he moved in the direction of elections, he might have saved all the good results of what they had done in terms of education and health. People probably would have retained those policies.

Robinson

You point out that from your impressions of him, he had a great personal arrogance, with the three-hour speeches on every subject under the sun. He did know a lot, but thought he knew everything. And it gets to this idea that, as a leader of people, you have to have balance. You have to have a certain arrogance because you’re accepting a position of leadership, and you’re oftentimes going against public opinion or trying to convince the public to support you; on the other hand, you are the representative of the people, you’re there to carry out their will, and you have to be humble and to listen. So, based on your experience in leadership, how do you strike that balance between getting ahead of the public and carrying out the public will, between having humility and a little bit of arrogance?

Broadbent

I have no magic formula. Every politician is going to do that on his own or her own by judging the situation that we’re in, by respecting the people that you differ with, and providing movement with care. But also something I want to emphasize is it’s important to move and to change the social democratic tradition. If you don’t, you just risk ossification, which produces ongoing inequality. Moderation of agenda mustn’t turn into abdication of a socialist agenda. I think both things are important. One is to respect people, but the other is to respect your own tradition, with the obligation to move ahead.

Robinson

I want to just conclude here by asking you to give us just a few thoughts on the meaning of the social democracy that you have spent seven decades, as you say, seeking. How will we know when we have found it or if we get near it?

Broadbent

The gist of the book is we will never get near it, but we keep struggling for it. And “near it” means near the final goal. We can move towards a society that is more equal in its outcomes, enabling people to have a life of joy and satisfaction. Different social democratic indicators can be achieved. But there will always be a constant struggle. We can see that in terms of market-based incomes today. Everywhere in the world where there are social democrats, there’s a continuous fight to stop the rich from gobbling up everything and to bring a greater share to the majority. And the message of the book, whether one agrees or not, is that there will always be an ongoing struggle. As long as we have a market economy of any kind, we’re going to need, for progress, a social democratic agenda. So that’s it!

Transcript edited by Patrick Farnsworth.