The Lessons of Vivek

Some tips on how to bullshit your way through life from upstart, attention-hungry, deeply annoying presidential candidate Vivek Ramaswamy.

In the past year, millions of people have learned the name “Vivek Ramaswamy,” whether they wanted to or not. A relative newcomer to politics, Ramaswamy has propelled himself into the national spotlight through his attention-grabbing performance in four Republican presidential debates—where, among other things, he has called the GOP a “party of losers,” started a personal feud with Nikki Haley, and endorsed the profoundly racist Great Replacement conspiracy theory onstage. Like Donald Trump before him, Ramaswamy has found that being loud and belligerent pays off. Like Trump, he has a short, pithy slogan—“TRUTH”—that he’s slapped on overpriced baseball caps. But Ramaswamy is pitching himself as a new kind of Republican: a Millennial at home with new technology and cultural trends, and a man of Indian heritage (whose parents immigrated “legally,” he likes to remind us) who can appeal to diverse voters in a party whose image is older and whiter than Moby Dick. He desperately wants you to believe that he’s the future of the GOP and a bold, visionary leader for the United States as a whole.

It’s all a sham. More than any politician we’ve seen since Pete Buttigieg, Vivek Ramaswamy is a hollow shell. He knows how to appear smart and charismatic, and when he’s standing next to someone like Ron DeSantis or Chris Christie, he easily outclasses them. (This isn’t a huge achievement. Most people seem charismatic compared to DeSantis and his rictus grin.) But Ramaswamy’s actual politics don’t hold up to scrutiny. He portrays himself as a bold truth (or TRUTH) teller, but he has a long track record of fast-talking and deception, both in business and politics. He capitalizes on his youth but endorses policies that would harm young people. He says inflammatory things for attention, rides the wave of media coverage, and then changes the subject. Look into his background for half an hour, and you’ll find a cavernous void where integrity, principle, and care for the average American should be.

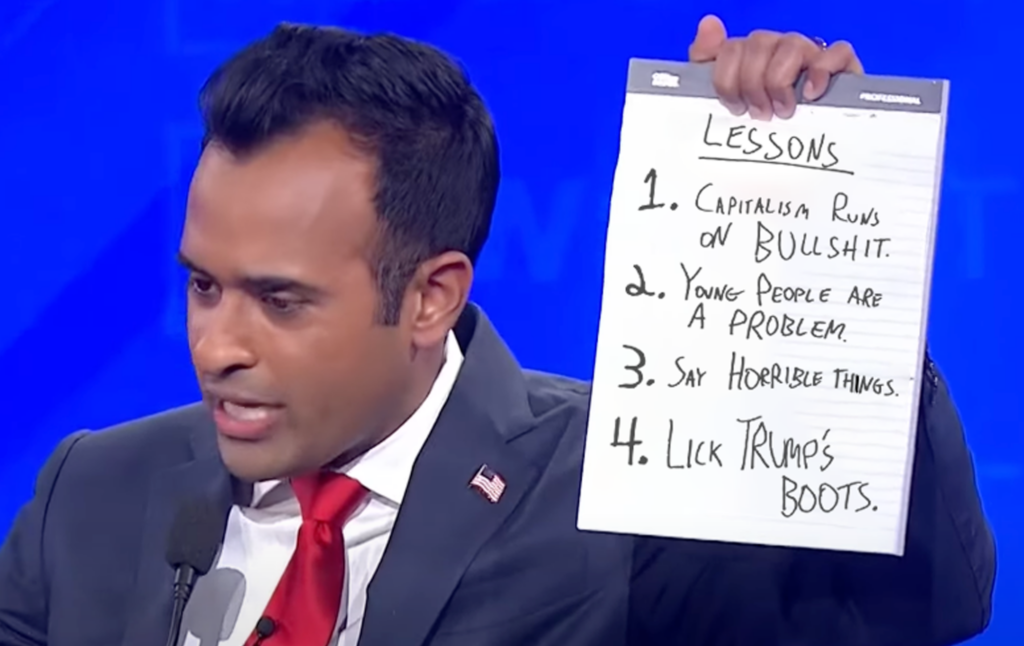

To illustrate these points, let’s look at just four of the lessons our friend Vivek has learned in his short career.

❧ Lesson #1: Capitalism runs on Bullshit

As Ramaswamy would be the first to tell you, he’s “not a professional politician.” In fact, he didn’t even vote in the 2008, 2012, or 2016 presidential elections, having become “jaded” by the candidates available to him. (This, at least, is relatable.) But if he wasn’t an aspiring politician until recently, who was he?

Well, he was a finance guy, which should raise alarm bells. A particularly fawning profile in Forbes calls him “whip-smart” and “entirely self-made” and notes that his net worth—hovering around the $1 billion mark, depending on market fluctuations—makes him “the second-wealthiest person competing in the Republican presidential primary, behind only Donald Trump.” In recent years, he has invested $25 million in the right-wing YouTube alternative Rumble, along with stock holdings in more mainstream companies like Microsoft, Lockheed Martin, and Home Depot. He’s also the founder of an “anti-woke” hedge fund called Strive, which opposes DEI (Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion) and ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) policies within large corporations, even when shareholders want them. But it’s how he originally made his money, not how he invests it now, that’s really interesting.

In 2014, Ramaswamy founded a biotech company called Roivant—the “Roi” part stands for “Return on Investment,” showing where his priorities lie—which he dubbed “the Berkshire Hathaway of drug development.” Its business model was basically to dig through bigger pharmaceutical companies’ trash and buy up, at rock-bottom prices, the patents to drugs that were abandoned by their original developers. Roivant would then develop the discarded drugs through a portfolio of subsidiary companies, each focused on a particular area of medicine. Today, the company’s offshoots include “Genevant” (genetics), “Dermavant” (skincare), “Hemovant” (blood), and “Immunovant” (the immune system), among others. But it was the now-dissolved Axovant, focusing on neurological diseases, where Ramaswamy first found major financial success. And that’s where the questionable business dealings come in.

Axovant’s signature drug was intepirdine, aka RVT-101. It’s a receptor antagonist, meaning that it blocks or interferes with the action of receptor proteins, and it was originally developed by GlaxoSmithKline, who thought it might be useful as a treatment for Alzheimer’s disease. However, after conducting four Phase 2 clinical trials, GSK found that only one showed a “small but dose-dependent” effect, while the other three “failed to meet their primary endpoints.” At that point, they stopped development, and Roivant snapped up the patent for $5 million. (Pocket change, by industry standards.) Soon afterward, a four-person team that included Dr. Geetha Ramaswamy—Vivek’s mother, and a geriatric psychiatrist by profession—conducted a new Phase 2 trial, which just happened to defy intepirdine’s previous record of failure.

Armed with these new trial results, Ramaswamy and his business partners took Axovant public in June 2015. Initially offered at $15 a share, the company’s stock nearly doubled in price on its first day, closing at $29.90 and making $315 million in the process. It was, at the time, the largest IPO by a biotech firm in Wall Street history, eclipsing the $264 million raised by Juno Therapeutics the previous December. Flush with success (and cash), Ramaswamy went on CNBC’s Mad Money to sing the praises of intepirdine to host Jim Cramer:

Cramer:

If you were a hedge fund manager, and you got shares in stock, and you just had seen Axovant—would you have rung the register today?

Ramaswamy:

So…. let me actually speak directly to it. I actually think the potential opportunity here is really tremendous for delivering value to patients. There’s over 5 million patients who suffer from Alzheimer’s disease in this country alone, and if you think about it—we own global rights to a drug that has already demonstrated, in a large Phase 2b study, efficacy in the two parameters that the FDA has historically required for new Alzheimer’s disease drugs. And actually, we’re only one—we believe—we’re only one additional Phase 3 study away from the approval of this drug on a global basis.

Bolstered by grandiose statements like these, Axovant’s stock price continued to rise in the following months, remaining consistently above $100 through the fall and winter of 2015. Late that year, according to the New York Times, Ramaswamy “sold off a portion” of his “suddenly extraordinarily valuable” shares in Roivant—which controlled roughly 80 percent of Axovant—to Viking Global Investors. He then reported a personal income of more than $38 million on his 2015 tax return, “most of it from capital gains.” It was the first time he’d made more than $1 million in a single year—and then it turned out the drug didn’t work. In September 2017, Stage 3 clinical trials revealed that intepirdine does not, in fact, treat Alzheimer’s disease effectively, as Ramaswamy had spent all that cable-news airtime boasting it would. Axovant’s stock price immediately plummeted, and it lost 70 percent of its $2.6 billion value within a few days’ trading. By 2020, the company—now valued below $5 a share—had rebranded as Sio Gene Therapies, and in April 2023 its shareholders voted to liquidate it altogether.

So, just to recap: Ramaswamy bought the patent for an Alzheimer’s drug that had failed the majority of its clinical tests, touted its “potential” as “tremendous” using a new test conducted in part by a member of his family, took his company public on that basis, then sold millions of dollars worth of his shares before the drug failed and the company crashed. As several commentators have pointed out, that all seems very, very sketchy. Speaking to the New York Times, pharmaceutical researcher Derek Lowe says that “whipping people up into thinking this was a wonder drug was unconscionable.” Newsweek’s Sam Nunberg goes further, saying that Ramaswamy “is a fraud—and always has been,” and Jeffrey Sonnenfeld, an Associate Dean at the Yale School of Management, writes that Axovant resembled a “classic pump-and-dump scheme.” If anything, they’re being too kind. There’s a strong resemblance between the Axovant story and that of Elizabeth Holmes, the disgraced founder of Theranos who briefly got extremely rich by marketing a blood-testing machine that didn’t, in fact, work. The main difference is that Ramaswamy has maintained plausible deniability. He can claim he genuinely believed intepirdine was a miracle drug, and that he was caught off-guard like everyone else when it turned out to be a dud. This is the defense he actually makes, saying that “I thought we were in striking distance.” You can judge for yourself how credible that is.

In a way, Ramaswamy is actually a perfect role model for the 21st-century healthcare entrepreneur. We’re often told that privately-owned businesses are superior to socialized medicine, because competition between them encourages innovation—but all too often, the “innovation” that supposedly justifies this private market consists of things like intepirdine and the Theranos blood machine. In a market economy, it doesn’t particularly matter if you produce anything useful; what matters is your ability to convince people you have and drum up capital from investors. The whole system runs on hype, rumor, and speculation—in a word, on bullshit. (The rise of the NFT, a commodity that doesn’t actually consist of anything, is another example of this pattern.) At his campaign events, Ramaswamy tells people they should “embrace capitalism,” and, well, of course he thinks that. Capitalism has worked out just great for people like him. It has allowed him to receive wealth beyond the wildest dreams of any actual scientist, doctor, or nurse who has helped save people’s lives, just for going on CNBC and talking about a hypothetical drug. But should that behavior really be rewarded? And how can such a person possibly be trusted with political power?

❧Lesson #2: Young People are a Problem

Flash forward a few years, and we find Ramaswamy in full presidential campaign mode. He stands out from the field of Republican mediocrities around him, both because of his cultural background—if elected, he’d be the first Hindu president, an awkward fit for a GOP increasingly obsessed with Christian nationalism—and his age, a mere 38. Throughout the campaign, he has used his relative youth as a selling point, saying that “it takes a person of a different generation to reach the next generation.” He’s the only GOP candidate to embrace TikTok, earning him pushback from rivals like Nikki Haley, who wants to ban the app. At a campaign event in New Hampshire, he invited a student protester inside to ask questions, saying that “I’ve been outside of rooms that I’ve tried to get into before” and could relate. (The protester came away unconvinced and said they plan to vote for Marianne Williamson.) In another recent publicity stunt, Ramaswamy joined social media influencer Kaz Sawyer for a video where the two surfed behind a yacht in matching suits and ties. He even has a rapping alter ego called “Da Vek,” which he busted out at the Iowa State Fair, performing an awkward rendition of Eminem’s “Lose Yourself.” Nobody can say he’s not trying hard, in a “How do you do, fellow kids?” kind of way.

The fact is, there’s a chasm between Ramaswamy’s political beliefs and the policy preferences of young people. On gender and sexuality, he’s chosen to be blatantly bigoted, listing “there are two genders” as the second component of his much-vaunted “TRUTH” and repeatedly saying that “transgenderism” is “a mental health disorder.” Polling shows this is an increasingly unpopular stance among young people, with 52 percent of adults between 18 and 29 saying a greater acceptance of transgender people is a good thing in a 2022 Pew survey. (Only 21 percent took an anti-trans position, while another 22 percent had no strong feelings either way.) On economics, Ramaswamy vocally opposed the Biden administration’s student loan forgiveness plan—which, although far from perfect, would have relieved millions of young people from the crippling burden of debt—calling it a “scam” that would “pay for anti-American gender-studies majors.” He describes himself as “unapologetically pro-life” and proudly told a CNN reporter he’d voted against the reproductive-rights referendum in his home state of Ohio. Only 29 percent of Americans between 18 and 29 agree with him.

Most notably, though, Ramaswamy is terrible on climate policy. He accepts that climate change exists but says that “the climate change agenda is a hoax,” and when asked if he would do anything as president to address rising global temperatures, has responded with a blunt “no.” If anything, this is a more baffling position than actual climate denial. Refusing to acknowledge the problem is at least coherent, if delusional, but admitting it’s real and then opposing any attempt to help is downright perverse. In something that vaguely resembles an explanation, Ramaswamy has posted the following to Twitter:

Inconvenient truths: 8x as many people die from cold temperatures as warm ones. The right answer to all temperature-related deaths is more abundance of fossil fuels. Abandon the climate cult. Drill, frack, burn coal. Embrace nuclear.

There are, to put it politely, several things wrong with this statement. In the first place, Ramaswamy seems to be using a discussion of weather temperature (whether it’s hot or cold outside) to distract from the fundamental issue of planetary surface warming (a phenomenon seen over time and caused by the burning of fossil fuels). In the CNN interview where he said he wouldn’t do anything about climate change, he admitted that warming was in fact happening, so his tweet is simply manipulative. It also indicates that Ramaswamy doesn’t understand that the trend over time will be for the weather to get warmer, too, and that the impacts of that heat will continue to worsen.

While it’s true that plenty of people die in cold weather conditions, it does not follow logically that we should therefore double down on the very activity that is causing planetary warming and contributing to extreme weather events. And it’s ludicrous to suggest that “temperature-related deaths” are the only negative effect of climate change. While any preventable death is a tragedy, deaths from extreme temperatures themselves are a drop in the bucket compared to things like the catastrophic flooding that recently killed more than 11,000 people in eastern Libya, and which scientists say was made 50 percent more intense by a changing climate. In the image below from Our World in Data, you can see that extreme temperature deaths are much smaller in magnitude than deaths caused by droughts, floods, and cyclones—all of which are made worse by climate change.

Climate-driven natural disasters have become routine occurrences, both in the U.S. and around the world. There’s also the prospect of increasingly violent conflicts over dwindling freshwater, which have already begun to break out across Africa and the Middle East. There’s the likelihood of refugee crises as a result of both those conflicts and the droughts and desertification that spark them. And then, of course, it’s unclear how “more abundance of fossil fuels” would help anyone, even in the cases that are directly heat-based, like the recent death of a UPS driver in 100-degree temperatures in Texas. Speaking to CNN, Ramaswamy would only elaborate that “we should focus on adaptation” and “look at the quality of our buildings. Look at the quality of temperature controls,” which isn’t exactly a satisfying answer. (Does he just mean building better air conditioners? Could it be that stupid?) More than any other issue, this refusal to treat climate change as a crisis in need of serious action is a slap in the face for young people, 59 percent of whom said they would support such action “even at the risk of slowing economic growth” in a July poll. Ramaswamy’s policy choices would very literally set fire to their future, and he doesn’t care.

None of this is new, of course. The Republican party has had a Young People Problem for a while, for all these reasons and more. In 2020, fully 65 percent of voters aged 18-24 went for Joe Biden over Donald Trump, a crushing margin to lose by in any demographic. That’s a big part of why people like Chris Christie want to ban TikTok, blaming the platform for “polluting minds” with viewpoints they disagree with. It’s also a significant factor in Ron DeSantis’s deranged drive to ban books in Florida schools and the parallel push to insert PragerU propaganda into them. The goal is to create more young conservatives to counter the general leftward trend. (Needless to say, the idea that conservative beliefs could be unpopular for a reason is never considered.) To deal with the Young People Problem, Ramaswamy has his own unusual and rather disturbing approach. If he can’t persuade young voters to agree with him on the issues, he’ll just take away their right to vote.

This should be an absurd piece of satire, but it’s an actual proposal. You can find it on Ramaswamy’s website, where he calls it “civic duty voting.” His argument is that “the Constitution does not expressly guarantee universal voting,” since “we live in a Constitutional republic, not a direct democracy.” Therefore, he has concluded that “Voting is a privilege, and civic duty is a proper precondition for enjoying that privilege.” In other words, he thinks the U.S. should pass a constitutional amendment to raise its “standard voting age” to 25. If someone below that age wants to vote, they’d have to either A) pass a civics test “identical [to the] one we already ask law-abiding green card holders to pass” or B) serve in the military for six months. This, Ramaswamy claims, would give young Americans a “sense of shared purpose and experience,” and could actually increase turnout among the notoriously poll-shy age group by making the ability a “coveted privilege.” As Current Affairs’ Stephen Prager has pointed out, Vivek isn’t the only right-wing figure to propose disenfranchising the young. Some pundits, like libertarian radio host Peter Schiff, want to go even further and raise the voting age to 28. But as an active presidential candidate, Ramaswamy is probably the most prominent U.S. politician to endorse the idea to date.

So why, exactly, is that idea hideously wrong? In a July interview with Breaking Points’ Krystal Ball and Saagar Enjeti, Ramaswamy said he hasn’t heard a good argument against making young voters take a civics test, and that he’d “stand by and wait” for one. So here it is. The most important point is a little thing called “the consent of the governed,” which even the so-called Founding Fathers agreed that a legitimate government must have. The term is not “the consent of the well-informed,” “the consent of the civic-minded,” or even “the consent of the mature.” Those things might be desirable in a voting population, but the lack of them does not justify taking away the ability to vote. It’s perfectly legitimate, for example, for someone to have no idea how many U.S. Representatives there are, or what Benjamin Franklin is famous for—two of the questions on the immigration civics test Ramaswamy wants to use—and simply decide how to vote based on things they hear in the candidates’ speeches, or how government agencies directly affect their daily lives. Even people who don’t score well on IQ tests, or who have developmental disabilities, have a fundamental right to say what kind of leaders they want. For a Harvard and Yale graduate to try to take that right away, and make it conditional, is elitism at its worst. The government doesn’t get to set criteria for having a voice in the government, for the simple reason that the citizens are above the state, not the other way around. Voting tests and military-service requirements reverse this relationship, so that the people are no longer sovereign. They would create a two-tiered system within the age group (18-25) they would affect, resembling the right-wing power fantasy of Robert Heinlein’s Starship Troopers. There would be a strong class bias, as the political views of people with access to a high-quality civics education would be privileged, while the views of people who went to poorly-funded, struggling schools would be disregarded. For a conservative politician, that’s extremely convenient. For the basic principles of a free society, it’s disastrous.

❧Lesson #3: When in Doubt, Say Something Horrible

By now it should be fairly obvious that, while he might basically believe in his awful ideas, Vivek Ramaswamy is also a massive troll. He’s a walking embodiment of the saying, often attributed to P.T. Barnum, that “there is no such thing as bad publicity,” and there seem to be no depths of taste, sense, or common decency that he won’t sink to either. More than any of his GOP rivals, he has copied the Trump playbook for manipulating the media. The process is simple: first, you say something cruel, stupid, or nonsensical (ideally all three.) Second, you sit back and watch the news media report on your statement, debate it, even condemn it—but crucially, spend time talking about you, and enhance your standing as an important public figure. Then, if there seems to be backlash, or if attention shifts to someone else, just say a new heinous thing and repeat the cycle. This can be kept up indefinitely.

For a useful case study, we can look at a sequence of provocative statements Ramaswamy made in late August and early September of 2023. On August 25, he referred to Representative Ayanna Pressley and author Ibram X. Kendi, both of whom are Black, as “grand wizards of the modern KKK” during a town hall appearance in Iowa. He was responding to Pressley in particular, who’d spoken critically about “brown faces that don’t want to be a brown voice” in politics. Perhaps Ramaswamy felt seen—but clearly, he had no interest in engaging in an intelligent debate about Pressley’s views on race, instead opting to call her one of the most offensive and inflammatory names imaginable. Both Pressley and Kendi were outraged, as you might expect, and the controversy was all over the news, inspiring TV segments on MSNBC, regular NBC, NewsNation, and CNN, along with articles in The Hill, Politico, Esquire, USA Today, the Washington Post, the New Republic, and even BET. In other words, the comments had done their job: to inspire a Ramaswamy-based news cycle, ensuring everyone would keep talking about him and not, say, Asa Hutchinson. (Remember Asa? Of course not.) By September 8, he’d squeezed all the juice he could from race-baiting, and moved on to a new source of outrage, saying that he wants to deport the children of undocumented immigrants, even if they’re born in the United States. He brings out new provocations a few times each month, whether it’s calling transgender people a “cult,” threatening to fire every federal worker whose Social Security number ends in an odd digit, or saying there should be three cops in every school. He appears to have three different positions on Israel, depending on who’s he talking to. It’s all gas in the tank.

Again, this is a tactic pioneered by Donald Trump, who moved from mocking a disabled person to calling Mexicans rapists to saying he could shoot someone and not lose voters with a greasy, sluglike ease. By some estimates, Trump’s ability to stir up outrage netted him $2 billion in free media airtime in 2016 alone, and Ramaswamy has proven himself a capable imitator. If anything, he may be more adept than Trump in the long run, because he can perform a passing imitation of a normal, likable human being when he wants to. But the whole thing was gross in 2016, and it’s still gross now.

❧Lesson #4: Trump is Going to be the Nominee. Lick his boots now.

Sooner or later, any discussion of the 2024 election comes back to that name: Donald Trump. The ex-president has loomed large over the past three debates, despite—or because of—the fact that he refuses to attend them. And really, he has no reason to. According to a recent poll from Emerson College, Trump commands 64 percent of the Republican vote, with his nearest rival being Nikki Haley at 9 percent, and everyone else trailing along in the single digits. Basically every poll conducted about the GOP primary looks like this. Sometimes it’s Ron DeSantis in a distant second place, and one time it was even Chris Christie, which must have been exciting for him. But nobody has seriously put a dent in Trump, and nobody will. Barring a jail sentence or a catastrophic heart attack, he will be the Republican nominee—and for his core voters, the first of those wouldn’t even be a deal-breaker.

Once again, Ramaswamy has the dubious honor of being the smartest of his peers, because he’s the only one that seems to grasp this basic fact. The other candidates seem to think, for whatever reason, that they could actually beat Trump. They go out of their way to antagonize him, either by raising concerns about his fitness to lead (which got Mike Pence exactly nowhere), or by taunting him as “Donald Duck” for “ducking” the debates (Christie’s stroke of genius.) Only Ramaswamy seems to understand that the Republican primary was over before it began. Unlike the others, he’s not running for President. Not really. He’s running to be Trump’s right-hand man.

When you look at it in this light, Ramaswamy’s campaign makes perfect sense. It’s the work of a really breathtaking sycophant, pitched to an audience of one. Ramaswamy has copied both the style of Trump’s politics, with the TRUTH hats and the shock-value media tactics, and the substance of Trump’s favorite hot-button issues. He rails against China like Trump, demonizes immigrants like Trump, and joins Trump in lashing out against the RNC leadership using one of the ex-president’s signature words, “losers.” He even lies like Trump, claiming that he “can’t travel to China” because his opposition to its government is just too bold. (In reality, he merely received advice against going there.) He has badgered all the other candidates, especially Mike Pence, to “Join me in making a commitment that one day you would pardon Donald Trump.” (Ramaswamy had said a month prior that he would pardon Trump if he were convicted for his mishandling of classified documents, falsifying business records, and insurrection-related crimes.) At the first GOP debate in August, he looked straight into a Fox News camera and declared that “President Trump, I believe, was the best president of the 21st century. It’s a fact.” After he said that, veteran Republican political consultant David Kochel remarked on the tone of Ramaswamy’s comments, saying that “I don’t understand the strategy behind ‘I’m just going to run to praise the person I’m running against.’” But somewhere in the heart of Mar-a-Lago, Trump was watching. The next day, he posted to Truth Social that “This answer gave Vivek Ramaswamy a big WIN in the debate because of a thing called TRUTH,” adding a jaunty “Thank you Vivek!” for good measure. He got the message, even if Kochel didn’t. The flattery worked.

Although it’s shameless and distasteful, licking Trump’s boots like this is actually a pretty good strategy. It opens several avenues for Vivek to come out ahead. In the first case, he could eventually be named Trump’s running mate. During an August interview with Glenn Beck, Trump himself seemed to seriously consider adding Ramaswamy to the ticket:

“He’s a smart guy. He’s a young guy. He’s got a lot of talent. He’s a very, very, very intelligent person…. He’s got good energy, and he could be in some form of something. I tell ya, I think he’d be very good. I think he’s really distinguished himself.”

For Trump, Ramaswamy could be a useful human shield against accusations of racism. He could also lure in voters who care about “representation” for its own sake, and might see him as a symbol of growing diversity in the GOP. It’s far from certain he’d actually get the VP nod, since other people could fill the role of Trump’s Non-White Friend equally well, like Ben Carson or Tim Scott. Or the ex-president could choose to focus on gender instead of race, choosing someone like South Dakota Governor Kristi Noem. In that case, Trump’s reference to “some form of something” could instead mean a Cabinet position for Ramaswamy, like Secretary of Commerce or, given his biotech background, Health and Human Services. (Call it the Buttigieg Scenario.) Finally, there’s a third possibility: that some unexpected disaster could take Trump out of commission. This isn’t a particularly long shot, given all the criminal indictments he’s currently under, to say nothing of his age and largely McDonald’s-based diet. And if Trump did have to drop out, it’s the candidate who spent all that time praising and emulating him, not the ones who tried to tear him down, who’d be well-positioned to become the heir apparent to the MAGA movement. An apprentice, if you will.

There’s one problem, though. It’s only recently, after he officially became a candidate, that Ramaswamy’s toadying kicked in. In the past, he was a lot more critical of Trump, and those old remarks keep coming back to haunt him. For instance, in his 2022 book Nation of Victims, he wrote that “while Trump promised to lead the nation to recommit itself to the pursuit of greatness, what he delivered in the end was just another tale of grievance, a persecution complex that swallowed much of the Republican party whole.” In a tweet from January 12 of 2021, he went even further, saying that “What Trump did last week was wrong. Downright abhorrent. Plain and simple.” And yet, in the space of just two years, his assessment of Trump went from “abhorrent” to “the best president of the 21st century.” In a recent TV interview, MSNBC journalist Mehdi Hasan tried his best to pin Ramaswamy down to a coherent position:

Hasan:

What did Donald Trump do, in your view, that was “downright abhorrent”? Second time I’ve asked that question.

Ramaswamy:

The thing that I would have done differently, if I were in his shoes—

Hasan:

That’s not what I asked, Vivek, with respect. What did Trump do that was “downright abhorrent”? It’s a simple question. It’s your words, it’s onscreen.

He never got a straight answer. Instead, Ramaswamy just kept waffling, saying that “failing to unite this country falls short of what a true leader ought to do,” and that “That is why I’m in this race, is to do things differently than any prior president has done them.” Looking back at the footage, you almost feel embarrassed for him. It must be humiliating to be confronted with things you said quite recently, and have to shift and dodge around your own words, just to gain favor with someone who might not even care.

Looking back at these four aspects of Vivek Ramaswamy, it’s striking just how little substance there is to his politics. In a leaked memo, a conservative super PAC urged Ron DeSantis to start calling Ramaswamy “Vivek the Fake,” and that actually feels fairly accurate. There are few things we can point to with any certainty, and say that Ramaswamy truly believes them. Sure, his rhetoric is generally right-wing, and he recites all the right buzzwords. But even his boldest declarations, like “embrace capitalism” or “there are two genders,” don’t feel like strongly-held ideological commitments. There’s no sense that he’d actually sacrifice anything for those beliefs. Instead, Ramaswamy’s guiding principle seems to be pure ambition. If he thought it would secure him greater power, fame, or wealth, he might embrace democratic socialism and trans rights tomorrow. After all, we’ve seen him completely reverse his stated beliefs on Trump when it became convenient. Why wouldn’t he do the same with any other subject? There’s a precedent for this kind of thing, as people like Elon Musk, George Santos, and even Trump himself have attained great success by being entirely untrustworthy. We live in the Age of the Bullshitter. Ramaswamy just delivers a particularly large pile of it.