How The Law Fails Women and What To Do About It

Prof. Julie Suk on why formal legal equality isn’t enough and what it takes to create meaningful gender equality under the law.

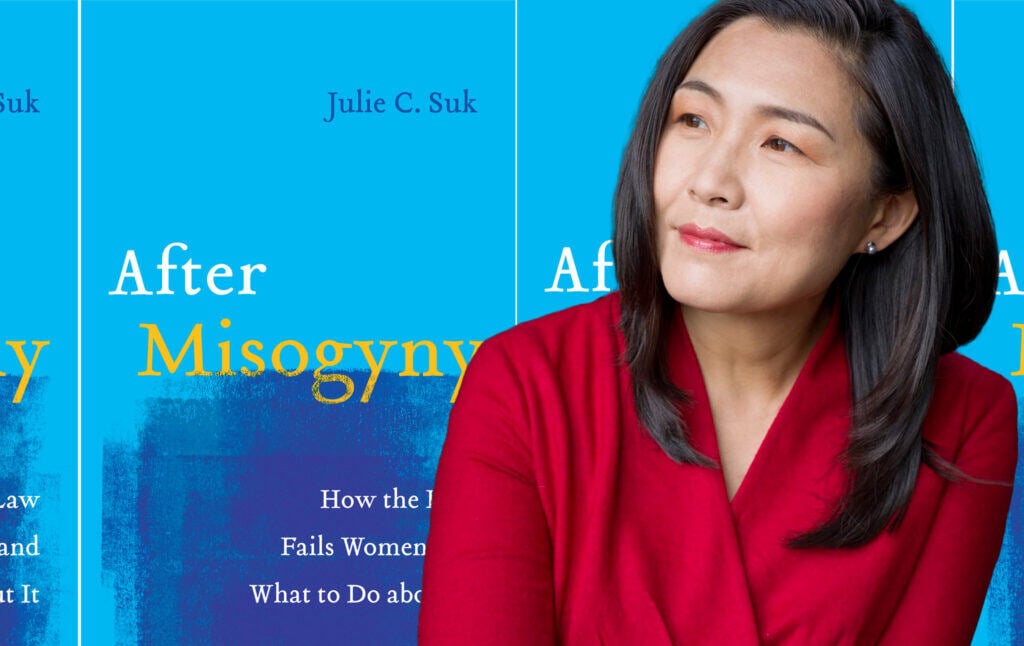

Julie Suk is a professor of law at Fordham University. Her book After Misogyny: How the Law Fails Women and What to Do About It is about why the law has not succeeded at eliminating patriarchy despite advances in formal gender equality. Suk acknowledges that feminist lawyers like Ruth Bader Ginsburg helped bring about equal protection under law, but shows that, just as “colorblind” racial policies leave existing hierarchies untouched, “equal treatment” fails to alter gender imbalances of power.

Suk also explains that, just as racism doesn’t have to involve “hatred,” misogyny shouldn’t necessarily be defined as hating women. Rather, she draws our attention to concepts she calls overempowerment and overentitlement; that is, misogyny is men’s excessive power over women and excessive sense of entitlement to women’s labor.

In this conversation, Prof. Suk explains her new framework for understanding gender inequality under the law. We talk about unpaid care work, abortion, and Prof. Suk even gives an interesting revisionist take on Prohibition, which many women saw as a way to curtail alcohol-fueled domestic abuse. Suk also explains how other countries around the world have tried to create real gender equality rather than just equality on paper, and gives her take on whether the Equal Rights Amendment would create meaningful equality or just more “on paper” equality.

The conversation originally appeared on the Current Affairs podcast. It has been lightly edited for grammar and clarity.

Nathan J. Robinson

I want to start with the concept of misogyny because providing a clear concept of misogyny is very important in your book. When people are accused of being racist, they often say things like, “I’m not racist, I don’t hate anybody.” And I think with misogyny, the same thing happens: “I couldn’t possibly be a misogynist, I don’t hate or despise women.” You argue that in some ways we should not think of misogyny as “hatred” of women, and you try and get us to a more accurate and helpful definition. What you point out is that it’s true that misogynists often don’t consciously “hate” women, but that doesn’t mean we don’t have a society saturated with misogyny. And so, let’s start with how you think we should conceive of the idea of misogyny.

Julia Suk

I think it might be helpful to think of misogyny as existing even if there are no misogynists. If you take a misogynist in the most conventional, everyday understanding, it is the woman hater, the man who hates women. There are still such people—there are misogynists—so I’m not saying that doesn’t exist. But I’m saying that even if you didn’t have a whole lot of misogynists, you could still have a legal structure that we could describe as misogyny because the hatred, violence, discrimination, and hostility towards women is just a manifestation of a larger dynamic that I’m describing and call in the book as “over entitlement” and “over empowerment.”

Specifically, that misogyny comes from a very long history of patriarchy. Patriarchy is in the culture and in the law. It’s a system that’s not primarily based on hatred or violence against women, although sometimes it was enforced by violence against women. It’s a legal system and a culture in which many things that are in the public interest are extracted from women. For things that are in the common good, women are expected to contribute for free, and it requires of them pain and forbearance and sacrifice that helps society survive and flourish. But all of those contributions are just expected and undervalued and undercompensated.

And I think the primary example of this has been the way that the law has regulated reproduction, including right now with the many abortion bans that we’ve seen go into effect since the Supreme Court’s decision last year in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization.

Robinson

I’d like to just read a little passage from page 85 of your book, under the subheading “Redefining Misogyny”:

“In the modern liberal political economy and legal order, some men, often by virtue of wealth or leadership positions in the economy or in politics, possess tremendous power over those who depend on them for their livelihood or future advancement. The law may authorize all persons including powerful men to hire or fire whom they pleased to engage in consensual sexual relations. Even in the absence of physical violence, empowered men can abuse these rights through aggressive sexual conduct towards persons who are subjected to their power. when men wield their power to maximize their gain without due regard for the vulnerable person, on the other side of the transaction, they abused their rights, they corrupt social relations and the economic and political institutions with which the law entrust them. understanding misogyny as over entitlement and over empowerment captures this important insight that lies beneath 21st century demands for gender justice.”

You’re writing about how even if there’s formal legal equality, we can have these massive power differentials in society.

Suk

Absolutely. I think that’s primarily what the #MeToo movement was about. The #MeToo movement was not just about sex or unwanted sex, it was about the fact that men in positions of power felt entitled, so as to make consent kind of irrelevant. So, through things like nondisclosure agreements—and of course, I think the recent indictment of Donald Trump in New York and the way that the hush money was, in fact, a form of corruption, which may or may not have criminal consequences—the overall structure is that people who are over empowered with wealth or political power have this sense of entitlement to women’s pain and sacrifice. So then, in a system in which we just declare everyone equal, that power dynamic becomes invisible, when in fact, it’s that power dynamic that makes significant anyone’s violence or hatred against women. But I think one of the most important insights of the #MeToo movement was that this was not really or even primarily about sex or sexual relations, it was really about power and abuses of power.

Robinson

You go through the whole history of patriarchal laws, and various women’s activist movements over the course of centuries that have successfully managed to get formal equality under law. But when we started thinking about these concepts of entitlement and power that you write about, the picture of formal progress of equality under law and the strides towards women’s equality looks a bit different.

Suk

Absolutely. And I think one pernicious dynamic in the United States in particular is that formal equality under the law, which was such an important achievement for legal feminism, has now come to undermine other mechanisms that might actually empower women. In the positive side of the book, “What To Do About Misogyny,” I look at something that has become a predominant trend and very important to feminists outside the United States, which is the adoption of gender parity rules regarding positions of power. So, rules that say, when you’re running for elected office, the political party must have equal numbers of women and men, or corporate boards need to have no more than 60% of one gender on that board. Those are the kinds of rules that formal equality has a real problem with. They say, that’s actually sex discrimination if you’re going to single out a particular gender and say that they get an advantage in a process by which you choose corporate directors, for example. So, I think that’s an important tension, that the thing that we often hold up as the achievement of formal equality comes to stand in the way of the empowerment and building of real infrastructures that would dismantle patriarchy and replace it with something more democratic and just, that all of those actions become questioned and challenged under a regime of formal equality. And that’s true not only for gender. Of course, we’re seeing it right now regarding race, that increasingly you have challenges to affirmative action. Those challenges to affirmative action, as a legal matter, are being presented as non-discrimination. You can’t help disadvantaged racial minorities because that’s “race discrimination.” And that’s a really important problem that I think we’re still struggling with in US law. But I think there are many ways in which that problem has been resolved in other constitutional democracies that is important for us to look at.

Robinson

It could sound paradoxical to people at first that the pursuit of equality under law can undermine equality. But this idea that you bring in is to think about power beyond the letter of the law, about who feels entitled to do what, and who is in control of decision-making. And then you see that if the law is not capable of changing the fact that a hugely disproportionate share of the power is held by men, who still dominate Congress and corporate boards and any sort of powerful position, then the law isn’t fixing the massive inequality.

Suk

When I discuss the law enforcing these dynamics or being inadequate—particularly formal equality being inadequate—to really dismantle patriarchy and transition us towards a more inclusive democracy, I’m also specifically thinking about the limits of courts. There’s a lot of law—there’s lawmaking and policymaking, but then there are courts. And I think the strategy in the United States regarding anti-discrimination as a principle of constitutional law has been to use the equality norm to attack, for example, Social Security policies that distinguish between men and women. Often what that means is that things get dismantled without replacing them with policies that would actually change gender roles within the family or lead to a greater participation by women in the political and economic sphere.

Robinson

I have heard these critiques of formal equality, that purely preventing discrimination isn’t going to fix the power problem. But in your book, you bring in some concepts that help us think more clearly about what we are trying to get rid of, if it’s not just rules that explicitly treat people differently on the basis of sex. What are we trying to get rid of? You bring in the concept of unjust enrichment, that this legal concept could help us understand what the problem is here.

Suk

So, if you think about patriarchy as being a system in which only men have legal rights and women are dependent—so even with just the vote, men are expected to exercise the franchise on behalf of their dependents: the wife and children. Married women don’t have property rights because only men do. These are all the things that are really important to first wave feminism. It’s believed that getting the right to vote is important, but is only the beginning to dismantling all these other structures. Of course, the solution appears to be that women should have equal rights under the law—equal property rights and equal rights to political participation. Under the logic of patriarchy, the reason women don’t have rights is not because women are hated, but because it’s expected that women have a certain role regarding childbearing and child-rearing, which would be somehow incompatible with the exercise of those rights. The expectation of women’s role of childbearing and child-rearing doesn’t change even after women are given equal rights regarding the vote, and even regarding just understanding women as welcome in some respects—at least not discriminated against—within the workplace as a matter of law. And so, I think part of the problem is that the cultural expectation is that women do all the childbearing and child-rearing, but then that’s not really considered a major activity of the state to support that childbearing and child-rearing. And this gets us back to the problem of abortion. We tend to think—and I think it’s because we’re conditioned by the Supreme Court’s landmark decision in Roe v. Wade—that the reason people have a right or should have a right to abortion is that having a child as a totally private matter, and therefore, the government should leave you alone to make your own choices about whether to have a child and how you’re going to raise that child, and so forth. I think in many other constitutional democracies, there’s a public recognition that having a child has enormous public consequences, including benefits to the society and the state, and that’s why the state has an interest in unborn life and in children. And what that means is that if you’re actually going to transition from patriarchy to an inclusive democracy, it may be important that you give women a choice, but it may also be equally important that you support caregiving. In many countries, including Germany, paid parental leave is considered a constitutional requirement because of this dynamic by which you understand that what it means for women to be equal is to be totally equal participants in both home and public life. So, that’s one example where if you are really going to deal with the unjust enrichment problem, there might actually be certain positive duties by the state to support childbearing and child-rearing, instead of it tacitly expecting women to do it for free without much choice.

Robinson

Let me see if I understand this correctly: under this framework, it’s not just that paid parental leave is a fair public policy, it’s that if you don’t provide women when they have children with paid maternity leave, you are almost violating their rights; the society is being enriched by their contribution, but not compensating it. And so, we should almost think of this in the same way we think of infringement upon property rights, speech rights, or other rights. It’s not just that it would be nice if we did this. It’s that to not do this is a violation of basic rights.

Suk

Yes. One framework that I introduced in the book, and in other writings that I’ve contributed to more specialized journals, is that we’ve got the abortion framework all wrong in thinking that the reason you should have a right to abortion is privacy. I say that the proper frame is taking property for public use. That is something we have in constitutional law under the Fifth Amendment, an explicit clause that says that the government can’t take your private property for public use without just compensation. And that’s been extended to mean that sometimes if the government passes some regulations that end up severely reducing your property value or make your property unusable, then under some circumstances you might be entitled to compensation from the government. I think that’s the way that we should think even about an abortion ban: women are being forced to contribute, but their contributions are then not valued.

The government does nothing, for example, about the very embarrassingly high rates of maternal mortality that we have in the United States, which disproportionately affect Black women. So, you force women to be pregnant, but you don’t address maternal mortality. But also, very importantly, we’ve had a very long struggle in this country for something that’s quite basic in many other countries, which is a legal requirement that pregnant workers be treated fairly and accommodated when their health requires it. That’s been a long struggle. About half the states passed laws on that in the last 10 or 15 years. Congress finally passed the Pregnant Worker Fairness Act in December 2022, after a lot of resistance.

But this is also something where if you’re forced to be pregnant or expected to bear a child, but there are high rates of maternal mortality, there’s no law that allows you to keep your job in health and safe conditions. And so, this work of creating a born child out of an unborn life is kind of expected, but totally not supported by the state. That’s what I’m talking about when I say that this is the over entitlement of society to women’s sacrifices, and that is actually the dynamic of patriarchy, which under patriarchy, and even after, is sometimes enforced by violence. That is the expectation that women have sex, whether they consent to it or not, and the expectation that they give birth and raise children, whether they really want to or not.

All of these things are what keep the patriarchal legal system going. Under patriarchy, it’s enforced by violence—by legal rules that deprive women of property and voting rights. But even when it’s not enforced by those things, we also have other mechanisms, even in modern societies, by which that unjust enrichment is left alone. And I argue that, too, is a legal order of misogyny, even if the primary problem in that legal order is not the violence of specific misogynists.

Robinson

There’s a lot of talk in the discourse about whether America is going to have enough babies be born, whether there will be a labor shortage, and not much talk about what the rights of those expected to perform the unpaid work. If you assume a society needs people, which we do, then having people who do the work and keep everything running is a benefit, and then you start to think that’s the work of creating the people for society. What I like is you reconceptualizing everything in a way that is very helpful. As you say, we have a tendency to think of it as a private decision, or almost like a selfish decision. And so, we think of things like maternal mortality—dying in childbirth—as like a failure to protect, when in some ways, we should think of it as an imposition. Are we failing to protect someone from this natural thing, or are we imposing it on someone and thereby violating their basic right?

Suk

Early advocates of feminism in the early part of the 20th century often made the analogy between military conscription and motherhood. These are gender differentiated ways in which you could say that men are expected, and often don’t have a choice. The whole idea behind the draft is that in times of need, that’s something that the state can extract. I think we should have a debate about that, too, but I think it’s long been assumed what makes the state what it is, is that it can draft men and expect them to die for the state. That’s the extreme version of it. But I think very often there’s been an analogy to motherhood, that it’s something that’s expected. But of course, as long as the draft has existed, it’s been compensated. We have people come back from war, or even if they haven’t served it in war as such, and we have the Department of Veterans Affairs—a whole system of support—and veterans preferences in certain job categories. So, the idea is that, fundamentally, we’re talking about that in a democratic state, what would it actually mean not just to have formally equality, but to really think of everybody as an equal citizen and equal participant in terms of what the state can expect from them, and how the state compensates or values their contributions?

Robinson

I have to ask you to respond to what would be the immediate libertarian objection to the analogy, which is that in the case of the draft, you receive a notice in the mail, but in the case of pregnancy, you do not receive a notice in the mail—you’re expected to bear a child for the good of the nation, and that there is a choice. I take it that you feel operations of social power mean there’s less of a choice than we like to think there is, but perhaps you could explain more why you think the analogy is valid, even if there isn’t the same degree of outright state coercion?

Suk

I think depending on the legal order that you live in, there may or may not be a choice regarding conscription, and there may or may not be a choice regarding motherhood. So, I would say in all the states in the United States right now that have instituted near total abortion bans, that it’s basically conscription into motherhood, especially when you have abortion bans that don’t have exceptions for rape. That’s basically forced motherhood.

Robinson

Certainly.

Suk

And one approach you could take is that under any understanding of morality, that’s just wrong. But I’m willing to entertain the possibility that if we have a theory of the state in which we accept that the state can conscript men into military service, and that’s the worldview from which you’re reasoning about abortion bans—I would say at the very least if the state thinks that it can conscript women into motherhood, there are some basic requirements so that motherhood doesn’t become slavery. Those requirements should be analogous to what men get for being conscripted, which is it paid maternity leave and safe conditions—it’s a little different with conscription because if you’re being sent to war, how safe is it going to be? But certainly, the idea is that veterans are then taken care of. I just think that we don’t think of the enrichment of society by motherhood, whether it’s forced or not forced. We don’t think of that enrichment as being unjust at all. That’s the frame that I’m trying to shift by rethinking what misogyny is, by thinking about misogyny as not just an isolated hateful act, but as a holdover from a legal system of patriarchy and everything it assumes and expects based on gender roles.

Robinson

You relay some of the history of changes in law over time, and I really want to touch on one of the more fascinating chapters of your book on Prohibition, which certainly upended my entire understanding of this. You point out that there’s this conventional understanding of Prohibition as almost a silly disaster, that there was this sort of collective delusion that we should ban alcohol, and then a few years later, America realized what a terrible mistake it had made. Why would we put an alcohol ban in the Constitution, and then repeal the ban? You tell this fascinating total alternative story that perhaps you could relay.

Suk

I don’t want to take total credit for it because many historians have worked on it as well, but it is true that I think that the dominant narrative is the one that you’ve described. There’s a very rich historical literature that looks at Prohibition as a long movement that runs parallel and often intersects with first wave feminism in the late 19th century. Some of the feminists or the suffragists that we celebrate, like Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, were equally involved, or at least they saw suffrage and temperance as being tied together. I see it as just another approach to some of the social problems that women experienced on the ground because of patriarchy. Men had control over all the family’s property, including their own wages as well as any wages that the mother or children brought in, and what that meant is that if they were spending it all on alcohol, that’d be a disaster for the economic well-being of the woman.

And of course, there’s a domestic violence narrative as well, that alcohol was contributing to domestic violence and unrest. Because of this, on the one hand, in the mid-19th century, temperance means “focus on men; try to persuade them not to drink anymore, and not to beat their wives” and so forth. But the movement starts turning towards institutions by saying, let’s not focus only on the men who are getting drunk and telling them to sober up, but on the alcohol industry and the male space of the saloon; let’s tell them not to serve alcohol to our husbands, or try to get them to shut down in our town. It’s only when women start organizing in the temperance movement against these businesses that the businesses start asserting property rights to get the women off their properties who are protesting and trying to make things better for themselves.

And it’s in response to corporations asserting their business and property rights that you get the women’s temperance movement saying that, actually, we need a constitutional amendment that prohibits the sale and manufacture of alcohol. Interestingly, the amendment did not address actual drinking, or even the making of alcohol at home. It was about the industry; it was about shutting down an industry that they thought was unjustly being enriched at their expense because men were getting all the family wages; men were getting drunk and then acting in ways that had severe consequences for the physical and economic well-being of women. And of course, they turned to a constitutional amendment—not right out the gate, but the constitutional amendment proposal grows out of other efforts to use law to improve their situation, which failed. For a while, they tried to sue the saloons; if their husbands got too drunk to actually work and support them, they would blame the saloons and tried to sue them. Those lawsuits had some limited success, but not really.

When there were many failures of law, that’s when the Women’s Christian Temperance Union and newly minted women lawyers (women were excluded from the legal profession for much of the 19th century) really started thinking about a major reset to the entitlements and power in society, and they sort of saw Prohibition as that major reset. I tell a positive story about that—don’t worry, I’m not trying to say we should have Prohibition part two. But I do think that the insight there is that people understand that it’s not focusing on men, or even specific small legal reforms, that’s the answer to this problem. You need to reset the entitlements and go after the institutions that are benefiting from the dynamics that make their life so miserable.

Robinson

I had understood that there was overlap between the suffrage and temperance movement, but you caused me to rethink what the whole prohibition movement was by pointing out that the whole argument being made by women for prohibition is that the purpose of the law is not just to guarantee equality and the vote, but to address these ways in which women are being harmed by over entitlement and over empowerment. When the law doesn’t step in to redress the harms that come from the disproportionate power of men, the law is effectively enforcing those power differences.

Suk

Yes. It’s not that the failure to act becomes misogynist action, although I think that sometimes that’s true. I’m also suggesting, as a historical matter, that we see that there’s a failure to act. I don’t think the failure to act is the same thing as active harm, but I think you can trace the ways in which anti-discrimination law doesn’t necessarily address the power dynamics in institutions that are dominated by men, and doesn’t actually translate into equal participation.

So, I think we can trace the ways in which that goes, and I’m not saying it’s necessarily the case that failure to act always enforces something pernicious, but you could trace the way that one thing develops from another. And with Prohibition in particular, there are the small steps where they think they have a legal game, like the ability to sue saloons.

But then once the saloon owner starts saying, we have property rights and you’re not allowed to protest on our property anymore, that’s when they say, maybe the solution is to not have a constitutional entitlement based on property to be in our neighborhood. That’s where they get this notion that there should be a resetting of entitlements in the Constitution regarding the manufacture and sale of alcohol.

Robinson

And that resetting of entitlements is almost to say that women’s rights not to be abused by alcoholic husbands are more important than saloons’ property rights, and that should be codified in law.

Suk

Right. I think that is what they were trying to say and do. I don’t think that that move always has to take this form. It’s always difficult for us to really take it seriously because it was about alcohol. But another good example is in Sweden in the 1960s. There was a debate about patriarchy and gender roles in the family. Of course, feminists tend to emphasize the expectation that women do all the childbearing and child-rearing, an expectation that is sometimes enforced by law. It’s enforced by law if you don’t give women a choice regarding childbearing, let’s say by banning abortion, or by excluding women from any roles in society other than motherhood, like if you exclude women from certain jobs or professions.

So, that’s how patriarchy enforces that. We tend to emphasize that harms women by excluding them from important opportunities to flourish as human beings. In Sweden, they started saying in the 1960s that it’s also harmful to men because men are also confined and excluded from certain forms of human flourishing if they’re expected not to spend a lot of time doing caregiving and having a meaningful caregiving relationship with their own children. But what’s so interesting in Sweden is that instead of fixing that problem by just saying, no discrimination on the basis of gender—that’s one move. They did not focus on the non-discrimination bit of it, they focused on policymaking. They said, let’s have childcare centers and fund them; let’s have paid parental leave for both mothers and fathers and fund that.

We’re still struggling with that. There was an executive order very recently where Biden greatly expanded access to childcare, particularly in the federal civil service, and in areas over which the President has power. But there’s a great dysfunction right now in American politics, by which we know that Congress in its current state is highly unlikely to do anything really meaningful to create access to child care on the federal level. There was a moment in the ’70s when a bipartisan Congress was doing that. But because of a political dysfunction that makes that impossible, we have some limited movement coming from the executive branch. This is why I think it’s so important not just to focus on equality, but also on the political institutions that can make policy to equality real. In Sweden, they were able to build childcare centers and fund parental leave for both mothers and fathers, in part because the major constitutional reform that they got in Sweden in the 1960s was not gender equality civil rights. They have a unicameral legislature that was able to implement a lot of social democratic policies. And it’s not just that it over-represented one group of people—there were plenty of electoral reforms to try to make that legislature more representative.

I feel we get really upset about the fact that the courts are no longer protecting a constitutional right to abortion, and we forget about the fact that in a normal, democratically functioning Congress, Congress should theoretically be able to fix that by passing the Women’s Health Protection Act.

Robinson

Yes, because polling shows people don’t want abortion criminalized. If we had a democracy, it shouldn’t be too much of a problem.

Suk

I think the problem is that sometimes we assume that we do have a democracy, and that people don’t want the Women’s Health Protection Act, but that’s not true. On the federal level, we have a democracy that over represents the people of Wyoming—severely over represents the people of Wyoming—as compared to the people of California. If you look at the design of the Senate—two senators for every state—the Women’s Health Protection Act was filibustered twice in the last Congress in the Senate. And now I think we’re facing numerous problems regarding the entrenchment of power in gerrymandering.

I think eventually there’ll be questions about how representative the more representative branch on the federal level of the House is. A lot of attention is being paid to a law that was passed in 1873 called the Comstock Act, in which anything that causes an abortion is criminally prosecutable on the federal level. It was passed by Congress at a time when patriarchy and misogyny, as I define it, were just the norm everywhere, and women didn’t have the vote at the time that law was passed—that law is now being brought back to limit abortion and potentially even in states that allow it. This is why I think that if we’re really going to get past misogyny, the conversation has to move beyond specific policy issues, or even formal legal equality, and into what the structures are by which we make law and power gets exercised.

Robinson

Yes. The first half of your subtitle is “How the Law Fails Women,” but the second half is “What To Do About It.” In many ways, it is a very constructive book. And one of the things you do throughout is look beyond the United States. The United States is a very dysfunctional country, as we indicated here, but also it’s a country that where oftentimes we’re unaware that there are things that other places in the world have addressed or made progress on that we haven’t; therefore, these are fixable problems. So, are there any other particularly striking examples of things that in other countries they have done that you think we should be looking to as a model as we think about how to move past misogyny in our own legal system?

Suk

I think no model is perfect, in that even in the models that we might say are relatively more successful than the United States, there are still problems. I just want to sort of give a couple of grains of salt to that effect. And also, no model is perfectly transferable because the United States is so different. It’s much larger, and the forms of diversity that we have along various lines may be different from other countries. But I do think that it is a trend in many other countries around the world that constitutional amendments have been deployed to address the problem that we started talking about earlier, which is the tension between formal legal equality and measures that actually empower women or empower disadvantaged groups.

I think we’re still struggling with that. In many other countries, when the court said, you can’t do affirmative action because that’s against our idea of formal equality, there were mobilizations in France, Germany, and Italy that led to constitutional amendments that made it clear that the law could authorize gender quotas to reach fairer representation of women in politics, for example, or a fairer representation of women on corporate boards and economic leadership. In my earlier book about the Equal Rights Amendment, the consistent and ongoing struggle for the Equal Rights Amendment just shows how hard it is to amend the US Constitution. We have an amendment rule that’s known to be one of the most impossible in the world.

And so, on the one hand, the positive models suggest maybe we should be amending the constitution instead of depending on the courts to give us our rights. But at the same time, there’s this larger project of really thinking about, why has the US Constitution, one of the oldest constitutions in the world, been so difficult to amend? How should we think about getting out of the cage that our amendment rule puts us in?

Robinson

I’ll take the opportunity of having an expert on the Equal Rights Amendment [ERA] here, and I’ll ask you something I have always wondered about: how significant do you think the Equal Rights Amendment would have been, or would be? Was it, and is it, mostly symbolic? Or do you think that it would actually be a massive, substantive, important change that would affect women’s lives for the better?

Suk

That’s a very big question. I think at the time that it was introduced 100 years ago in 1923, it could have enacted a massive change, but it wasn’t adopted in 1923. It was finally adopted in 1972. And I think had the states ratified it, we would have gotten significant changes. We got some of those changes anyway because even though we came three states short of ratifying the ERA, many states after they ratified it decided to get rid of some sex discriminatory laws, even without the ERA forcing them to do it. This is where I think that the ERA has already had tremendous effects, even without becoming law.

The ERA as politics has really changed the way people think about what the Constitution should do about gender. And that’s why people now talk about how the ERA is not really necessary because all the organizing for it changed hearts and minds about what they want gender relations to look like. We no longer formally need the law of the ERA to get a lot of the benefits of the ERA.

But honestly, Nathan, I think this is another unjust enrichment dynamic where women have changed the Constitution, but they aren’t founding mothers because there’s no text in the Constitution that we give them credit for. To the extent that we buy the narrative that the Constitution already protects gender equality, it didn’t come out of nowhere. It wasn’t there in 1787. It came out of women organizing, but they’re not given the status of constitutional authorship because we haven’t been able to complete the process by which the ERA is officially added to the Constitution.

And so, do I think that if we got it now, it would radically change the state of affairs? No, because we also live in a world where we expect constitutional rights to be interpreted and enforced by the Supreme Court. And after what I saw from the Supreme Court’s interpretation of the 14th Amendment, I don’t have high hopes that the current sitting Supreme Court is going to take the ERA and start protecting women’s rights in the most progressive direction. But that said, the ERA is a text that was written in 1923 and adopted by Congress in 1972 and arguably completed ratification in 2020. I think that’s definitely an improvement over the Supreme Court’s tendency to think that the only interpretation of the 14th amendment that’s really valid was the accepted meaning at the time of ratification in 1868. So, I think definitely having texts that were written and ratified in the 20th and 21st century is probably going to be a better ground for women’s rights than anything else we have in the Constitution.

Transcript edited by Patrick Farnsworth.