We’re Finally Getting The Media-Savvy Labor Militants We Need

It’s healthy for democracy to have prominent labor leaders who are both relatable and capable of articulating an uncompromising pro-worker message.

In the UK over the past couple of years, the head of the country’s railroad union, Mick Lynch, has become something of a household name. There’s been an ongoing dispute between the country’s Conservative government and rail workers, and in 2022 Lynch emerged as an effective spokesman for rail workers. Lynch’s exchanges with TV interviewers were master classes in communication. He faced a challenging task, because rail strikes caused significant disruption to Britain’s transit system, and it wasn’t obvious that the British public would be on the side of the rail workers when the trains weren’t running. But in part thanks to Lynch’s effective public advocacy, popular support shifted significantly in favor of the rail workers and against the government.

Lynch is now the subject of a forthcoming book, Mick Lynch: The Making of a Working-Class Hero, by University of Leeds professor Gregor Gall. Gall is a sociologist interested in the question of why Mick Lynch suddenly achieved prominence in Britain, where transit union heads do not usually become celebrities. For Gall, it was partly that Lynch was skilled at patiently making the case for his workers even in hostile forums. But Lynch also emerged at a time when there simply weren’t many “working class heroes” around to celebrate, a time of “historically low level of collective self-confidence and class consciousness of workers.” The head of the Labour party, Sir Keir Starmer, is so disconnected from the labor movement he has refused to even voice support for workers in strike actions. Jeremy Corbyn, the previous Labour leader, was grounded in the radical labor tradition but had been thrown out of the party by his successor. Britain lacked visible public champions for the rights of working people. (You can see in the YouTube comments sections of videos of Lynch’s interviews just how delighted people are to hear someone arguing in a forceful, plain-spoken way that everyone deserves to have their basic needs met and condemning the hideous inequality of 21st-century Britain.)

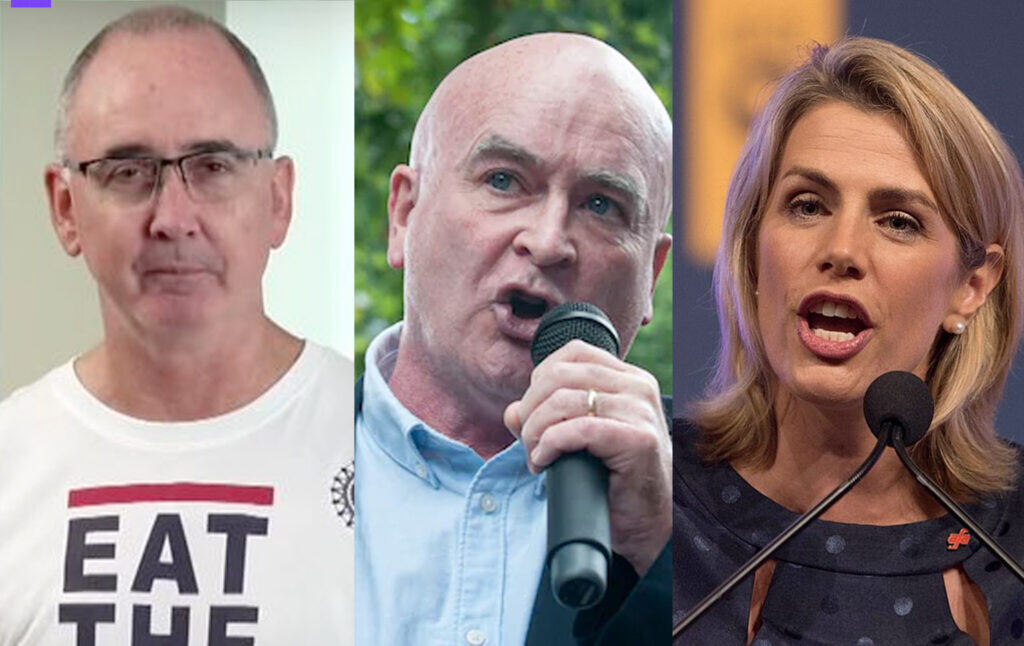

We now have an interesting parallel figure to Mick Lynch here in the United States: Shawn Fain, the United Auto Workers (UAW) leader known for his “relentless anti-executive rhetoric” and for his role in helping the UAW win historic contracts for its members. Fain is an uncompromising class warrior (the “Eat the Rich” shirt is not subtle) who sees corporate executives as enemies to be fought and defeated, not as partners. He also believes, to reference Jane McAlevey, in “raising expectations and raising hell,” meaning that he takes an aggressive negotiating stance but also understands that working people need to feel they deserve more. As he said in a speech republished in Jacobin:

For years, as a member of the UAW, and even during this current round of bargaining, I have found it heartbreaking to read comments from members and retirees with such low expectations. I’ve read comments such as, “you can’t get COLA [Cost of Living Adjustment] back, it’s gone forever.” Or “you can’t bargain for retirees.” Or “You’re asking for too much.” That is company talk. It comes from a company mindset and is the direct result of company unionism. It comes from the worst of our union’s history, of setting expectations low and settling even lower. And for many of us, who have yet to see our union fight hard and win big, it is hard to imagine what that would look like. Making bold demands and organizing to fight for them is an act of faith. It’s an act of faith in each other. Yes, these corporations are mountains, but together we can make them move.

Fain is actually a deeply religious man and frequently quotes Scripture. I’m not myself religious (nor is Mick Lynch, whom a protester once accused of being “anti-Christ,” although not the antichrist). But I can be moved by Fain’s invocation of the book of Matthew: “if you have faith the size of a mustard seed, you will say to this mountain, move from here to there, and it will move.”

Lynch and Fain have a few qualities in common. They’re clear about which side they’re on. They are articulate public ambassadors for the working class. And they’re relatable. They seem like ordinary people. This is good: we need public spokespeople for labor who demonstrate what it looks like to be an ordinary working class person fighting to improve their station. The rising public profiles of Sara Nelson (Association of Flight Attendants-CWA), Christian Smalls (Amazon Labor Union), and Sean O’Brien (Teamsters) feels like a throwback to an earlier era when labor leaders like Walter Reuther, Cesar Chavez, and John L. Lewis were known nationwide. Because part of the anti-labor strategy of corporate America is to present unions as aloof and parasitic, it’s important that they have likable and engaging public spokespeople.

Of course, we should always be suspicious of leaders. The Occupy movement of 2010-11 was highly influenced by anarchism and committed to an egalitarian “no leaders” philosophy. As a result, it didn’t produce any “personalities,” and that might be a good thing. After all, when movements are identified with individual people, it gives a misleading impression of how they work, and the identification of the civil rights movement with Martin Luther King Jr. and Rosa Parks has obscured the degree to which its success was the result of tireless organizing by people whose names do not appear in textbooks.

Power and fame also have a tendency to go to people’s heads. Behind the scenes, the story of Cesar Chavez was actually tragic, as Chavez became self-aggrandizing, dictatorial, and disconnected from the farmworkers. But he also became a folk hero, and because he was so personally identified with the farmworkers’ movement, criticizing him could feel like criticizing the movement. Already, we are seeing some worrying signs of the same thing at the Amazon Labor Union, with union members accusing president Christian Smalls of trying to stifle democracy within the union. Smalls is a charismatic, stylish, and compelling union leader, which makes it painful to think that he might not actually be the right person for the position. (I am not familiar enough with the facts to render a judgment on him, and it’s a matter for the ALU’s members.)

It’s good, though, that we have an emerging new set of labor leaders. People should be able to identify a labor leader, not just famous CEOs like Warren Buffett and Elon Musk. Labor leaders should appear on television and be quoted in newspapers. It’s going to be very difficult to rebuild worker power in this country, but part of the task involves making unions more visible, so that everyone knows what a union is and what a union does. Sadly, in a country with such pitiful union density as the United States, plenty of people don’t have more than the vaguest sense of what “labor” is (they might even associate the word “unionized” more with organic chemistry than workplace politics).

As I say, we need to be highly suspicious of people made famous by social movements. But I am also tired of knowing the names of endless loathsome politicians and having few visible public union organizers, and I’m gratified that that seems to be changing.