The Rise and Fall of Crypto Lunacy

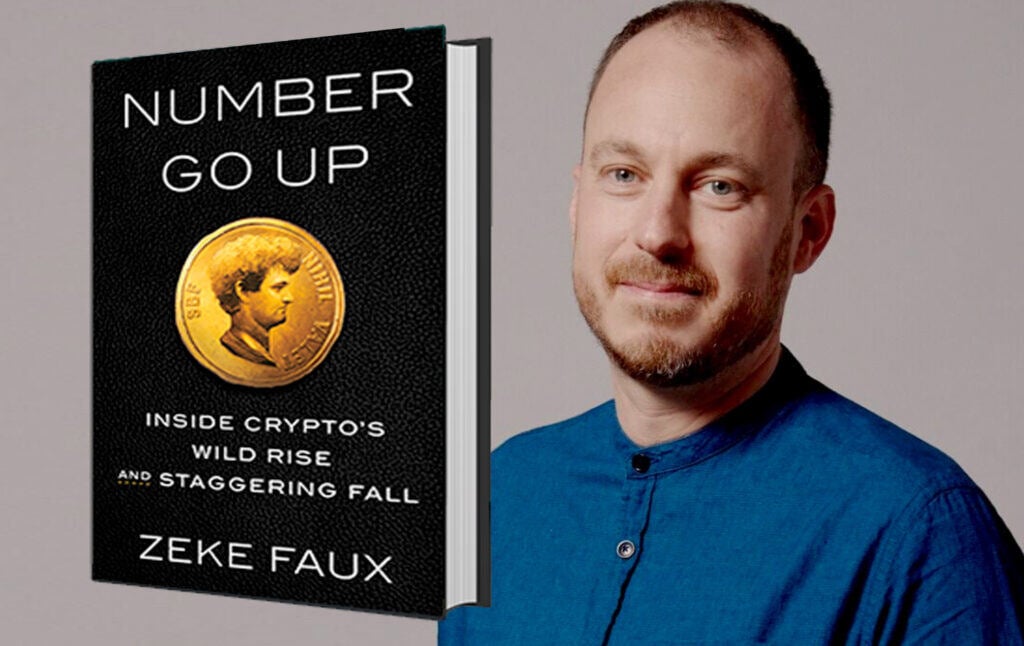

Financial reporter Zeke Faux, author of a new book on Sam Bankman-Fried and the bizarre world of crypto scams, joins to tell us what he witnessed in crypto-world.

Zeke Faux of Bloomberg News is the author of a fascinating and hilarious new book about the crypto world and the collapse of the Sam Bankman-Fried empire, Number Go Up: Inside Crypto’s Wild Rise and Staggering Fall. In contrast with Michael Lewis, whose recent book Going Infinite also looks at Bankman-Fried, Faux sees the scamming and lying of the crypto world for what it is, and his book is highly conscious of the harm done to victims by the fraudulence of Bankman-Fried and others. (Faux’s book begins: “‘I’m not going to lie,’ Sam Bankman-Fried told me. This was a lie.”)

Today, Faux joins to answer all of the most pressing questions about SBF, FTX, crypto, and the very dumb world of “NFTs,” like:

- When did SBF’s (alleged) crimes become detectable? Is Michael Lewis right that at the core of FTX was a “great real business” that was undone by bad luck?

- When Zeke confronted Jimmy Fallon about all the money people lost by investing in NFTs, how did Fallon justify promoting them?

- Since Sam Bankman-Fried rationalized his every action in terms of its “expected value” calculation, how did he justify playing video games all the time?

- Was SBF’s “effective altruism” ever actually sincere?

- Why would anyone ever have bought a “bored ape” image for millions of dollars?

- What insights about the human condition can be gleaned from examining the world of crypto?

The interview has been lightly edited for grammar and clarity. It originally appeared on the Current Affairs podcast.

Nathan J. Robinson

Do you know what people are saying about your book?

Zeke Faux

I have googled myself recently. Yes, I have to admit it.

Robinson

So you know, then, the most common comment about your book is that it’s the good book about Sam Bankman-Fried and cryptocurrency?

Faux

Yes, it’s pretty amazing. There’s also a book by Michael Lewis. Number Go Up was my first book, and I thought, “Oh no, I’m writing about the same topic as literally the most famous and successful nonfiction book writer around.” I was prepared to be crushed. It’s been quite a surprise and a huge honor that people have compared my book favorably to his.

Robinson

Right, and Lewis had a bunch of access to Bankman-Fried. The funny thing is that he has this kind of formula for his books. They’re about these underdogs, and he tried to write a book about Sam Bankman-Fried, who appears to be a criminal fraudster. It didn’t really work and people noticed that it didn’t work, and so in the reviews of this book you sometimes read that if you want to read a better book about this story, read Number Go Up by Zeke Fox.

Faux

Well, I’ll take it. Setting aside any questions about the rightness or wrongness of Michael Lewis’s take, when I finished Number Go Up, I was just thought, I spent two years going down this rabbit hole of crypto world, met so many crazy guys—not just Sam Bankman-Fried—traveled from El Salvador to Cambodia, and by the end, I was actually less worried about Michael Lewis. I just thought, this is the craziest adventure you will ever go on; how will you ever come up with like something this exciting to write about again?

Robinson

It is bizarre. Your book is populated by some of the most eccentric human creatures that I’ve ever seen. The whole phenomenon, in retrospect—and I guess it’s not over, but certainly the shine has come off crypto—you think, how did that happen? What was that? Why did this happen?

Faux

Yes, it is baffling to me. The book is a two-year effort to answer that question. And when I started out, I didn’t know very much about crypto. I’m seeing all these coins going up and up and up, and reading the same headlines as everyone about the guy who made $10 million off Dogecoin, a kid becomes Bitcoin billionaire after starting this new company, or Biden’s biggest donor is this guy with crazy curly hair who runs this exchange, FTX, and is worth $20 billion. None of it made any sense to me, and I thought it was all pretty silly.

And basically, what happened as I looked into it is that it was even sillier than I had thought. Every time I pulled back the curtain on one coin, or one company or another, I saw there was nothing there. And yet, what I realized was that it was actually having more of an impact in the real world than I had imagined. So, it was both sillier and more terrible than I thought when I started out.

Robinson

When you say that “when you pulled back the curtain, there was nothing there,” what do you mean? What was supposed to be true, and what did you discover when you looked closer?

Faux

What I am saying is that the crypto industry is amazing at public relations and at spinning the story that crypto is this innovative new technology that’s changing things, creating a more fair financial system, cutting out middlemen, and making it easier to send money all around the world. Even if you’re skeptical about crypto, it’s impossible to avoid these headlines and to not think there might be something to this.

But just to give one example, the Bitcoiners—who are kind of like their own clan and believe that Bitcoin is the one true coin and some of the craziest people in the crypto world—love to talk about El Salvador. I was at my first crypto conference—my introduction to the crypto world—and at the close of the conference, this prototypical crypto bro—a kid in a hoodie—was stomping around the stage cursing up a storm talking about how Bitcoin is saving El Salvador. He played a video of the president of El Salvador announcing in English to an audience of crypto bros in Miami—most people in El Salvador do not speak English—surprise world! Bitcoin is now legal tender in El Salvador.

People at the conference were literally in tears; the guy on stage was bawling; people in the audience were crying. I heard quite a lot about this experiment in El Salvador, and Bitcoiners painted this as a big success. You can go watch YouTube videos of them going to El Salvador and marveling at how they can buy a slushie with Bitcoin now or pay with Bitcoin at Starbucks because the president literally told every store that they’re supposed to take Bitcoin, and gave everyone in the country $30 worth of Bitcoin on an app if they download it.

But I went down there, and there was nothing to investigate. Nobody uses Bitcoin. It’s a made up story. The made up story is that there is this town called El Zonte, this little surf town where a guy from San Diego started teaching the locals about the magic of Bitcoin, and it created this whole new economy there.

And when I got there, at the first store I went to—this little stand on the side of the road—I asked the clerk for a bottle of water. He goes in the back—you order everything at a window—and comes back with a bottle of water and hands it to me at the window. So, I’m standing there with a bottle of water in my hand, and I say in my gringo Spanish, “Puedo pagar con Bitcoin, por favor?” [Can I pay with Bitcoin, please?] And the guy just grabs the water out of my hand, and says “Basura!” which is trash, and takes it away. He’s gone. He doesn’t even want to deal with me. He’s sick of these gringos who want to pay with Bitcoin. And that was typical—that was not just this one guy. Some stores even had signs that said, “We don’t take Bitcoin.” Get out of here you jerks!

Robinson

No matter what the President says!

Faux

So, I can’t say enough how made up the story is that El Salvador did anything with Bitcoin. Even headlines that expressed some skepticism about this experiment really overstate its impact. Most people that I spoke to in El Salvador had no opinion about this whatsoever. And I would say for the average person, maybe they got their cousin who’s good at computers to get the $30 out of the Bitcoin app somehow, and then they forgot about it. That’s the extent of it.

That’s just one crypto thing, and I had to go to El Salvador to debunk this. What I was trying to say is that pretty much any crypto headline is overhyped like this, and when you go look into it, there’s not much there. I can go on forever, but the New York Times ran a story, sort of towards the peak of this last crypto bubble, and the gist of it was, maybe there is something to this crypto thing, and maybe we should take the middle ground and not be so skeptical.

One of their lead examples was this app called Helium that paid you in crypto to run a wireless router; it was going to be this network of Wi-Fi around the country or something like that. And after the New York Times came out with this article, it came out that the company had claimed to have some important partnerships that were mentioned in the New York Times that were just not true. I’m not even talking about all the giant crypto companies that were revealed to be giant frauds. Even for the ones that were doing something in the real world, it wasn’t as good as they claimed.

Robinson

What comes to mind is the story in the book of all these people being paid in crypto coins to play a video game in the Philippines. It seems like there is a “real story” there in the sense that plenty of people saw the opportunity to make money, and they started playing the thing. But the crypto hype story is that some new way of running an economy is being built, or something real is being done that is going to transform the financial system, and that is never true. And to the extent that when you go and look at these things and something is happening, usually it collapses soon afterward.

Faux

Yes. I’ve been told by my lawyer to avoid the term “Ponzi scheme” as it implies criminal intent, but what you see, again and again, is a totally unsustainable bubble. That’s where the title of the book comes from: Number Go Up. And the crypto guys actually talked about this as a good thing. They say it’s the answer to the question, which is, why is Bitcoin going to go up? Or, why is the coin associated with this video game in the Philippines going to go up?

The answer is, if the price goes up, people will notice that and then new people will come and start buying. This buying pressure will make the price go up more, and then even more new people will notice, they’ll buy, the price will go up and up forever, and then we’re all going to make it. We’re all going to get rich, and have fun staying poor, if you don’t do it, too.

This just doesn’t work. We can’t all just buy and buy and buy and get rich that way. In the end, a coin or a company has to have some use in the real world. It has to generate value in real-world value somehow, and that’s what its price will be based off in the long run. It can’t just be: we all buy it, and if no one sells, we’ll get rich. It just never works that way.

Robinson

But once people are part of something like this, they have a very strong incentive to insist that it’s going to keep going up forever because they need it to not collapse. Once you’re in, you kind of have to have faith. If you become skeptical, you could poison the whole enterprise and lose all of your money.

Faux

One of my favorite ones that stated this sort of explicitly was called Olympus Dao. It was a coin that paid 8,000% interest or something like that, and they had a slogan that was “3, 3” that referred to game theory. It was basically saying, our Olympus coin is going to keep going up and up unless people sell; if we can all get together and stay in this quadrant of possibilities where nobody sells, it will keep going up and up and never collapse, so we can earn our 8,000% interest. And so, they would say “3, 3” to encourage everyone to stay in that good zone of not selling.

Of course, people sold. No one’s just going to hold on to their Olympus coin forever. And of course, the thing collapsed. But yes, once you buy in, you have to sort of become a cheerleader for whatever coin you’ve picked as the one to buy.

Robinson

I want to go back to what you said earlier about how it was not just that when you pulled back the curtain, it was sillier and more hype than you expected, but it was also more dangerous or had more serious impacts on the real world. Could you talk more about that part of it? Because on the surface, it looks just like a silly game being played by some fools who are welcome to lose their money.

Faux

Yes. So, early on, at this first crypto conference where the bro cried about El Salvador, I met Alex Mashinsky, who was running a big crypto company called Celsius Network. When he explained his business plan to me, I thought it was the dumbest plan I ever heard. Basically, Celsius Network is a little bit like a bank for cryptocurrencies: if you deposit your cryptocurrencies there, they paid interest of up to 18% a year, which is an insane interest rate, and then Celsius would give out loans, but at much lower interest rates.

So, this is like a backwards bank that’s made to lose money, or a Ponzi scheme. And I asked him, how is this going to work? How are you going to make money? And his explanations never really made sense. I wasn’t planning to write about him, but I asked him, just to be kind of polite, tell me about your company: how much money do you have? He said $20 billion, which is, even by modern standards, quite a lot of money. It was easy to laugh at him and the terribleness of his business plan, but I learned that money, from interviewing customers, came from regular people who were saving for retirement or to buy a house. They weren’t necessarily trying to get rich quick; they just wanted to earn, admittedly very high, too good to be true, interest rates of like 10 or 20%.

They bought into this story; they believed it. And there were several companies like this that were selling crypto as a safe way to save, earn interest, or fight back against the financial system which is rigged against you. And when these companies collapsed—Celsius failed last year and Mashinsky was arrested and charged with a big fraud—real people lost their savings.

One that stuck with me was someone who had been saving on a platform called Voyager that kind of had a similar pitch. She worked in a public school in New Jersey and had been saving to buy a house. She was a single mom. And when this platform collapsed, it was like the rug was pulled out from under her. It was a huge setback in her life and was really upsetting.

And so, it wasn’t all bros buying a thousand bucks of Dogecoin to laugh about it. These were real people who had lost their money, real people around the world. Another person from the book I speak to was a student in Nigeria who had been saving to go to college in Canada, and when a different crypto Ponzi scheme collapsed, he lost all his savings.

It was not all fun and games, and I just thought it was pretty offensive the way these crypto bros were making all these claims. Real people are believing them and investing their money and losing it. And as much as they would say it’s on the user to do their own research, these crypto companies were also spending huge amounts on marketing. The 2022 Super Bowl was filled with ads from crypto companies that were basically saying, if you don’t invest in crypto right now, you’re going to be left behind and a loser; the cool thing and brave thing to do is buy crypto right now. Fortune favors the brave, as Matt Damon said.

Robinson

And getting celebrities who have—I don’t want to say reputations for honesty—but someone like Matt Damon is a very well-liked guy. And I’m sure there are plenty of people who think Matt Damon probably wouldn’t be involved with an outright fraud.

Faux

Yes, and the one that he pitched, crypto.com, has not collapsed. But if you went on there and bought pretty much any coin, you would have lost a lot of money by now.

One of the main characters in the book is Sam Bankman-Fried. I spent a couple of days down in the Bahamas at FTX’s offices right after that Super Bowl, when things were going really, really well. I came into this pretty skeptical, and I said to him, “Isn’t it kind of distasteful that you are taking up these ads and encouraging people to gamble?” Even in the stock market, day trading is pretty much proven to be a money losing activity. There have been countless studies on it. If so, then day trading on crypto, where most of the companies are scams anyway, is definitely a money losing activity. Sam had claimed that he was an effective altruist, that all he cared about was doing good for the world.

Robinson

He just loved humanity.

Faux

We talked about this: is it good for the world to encourage people to gamble on crypto? And he never gave me a really satisfying answer. He tried to claim that he wasn’t telling people to gamble, and that they could do their own research and pick the best coins. Of course, he did not say, nor did I suspect, that in addition to taking out ads telling people to gamble, he was running a giant scam right in front of all of our eyes.

Robinson

I want to ask you about that. We mentioned that Michael Lewis has just published a book on this, and he went on 60 Minutes and infamously said that Sam Bankman-Fried and FTX had a legitimate business that was brought down by basically bad luck, and I guess he’s one of the few people endorsing his kind of defense narrative. Is there anything to that?

Faux

Even being very charitable, I would say no. What he’s trying to claim is that FTX the cryptocurrency exchange was a good cryptocurrency exchange. If you don’t know about cryptocurrency exchanges, it’s not that complicated. It’s just like E-Trade or something. So, picture an app: people send money to the exchange, and then they can go bet on all these different cryptocurrencies. When you sent in a thousand bucks and thought you were using it to buy Dogecoin, you’d open your app and see that you had all this Dogecoin.

In reality, the exchange had actually taken your money and lent it to Sam Bankman-Fried’s hedge fund, Alameda Research, which was making crazy gambles with that money. And when everyone started to get nervous and asked for their money or their Dogecoin back, it was revealed that the money was gone, and they couldn’t have their money back. That’s why he’s on trial for fraud. [Since this interview, Bankman-Fried has been convicted on seven counts of fraud and conspiracy.]

So, I think what Michael Lewis was trying to say was that had Sam Bankman-Fried not stolen the money from the exchange, it was a good exchange, people liked to use the app, and it could have been a perfectly good business.

But there are some problems with that. One is that testimony at the trial has revealed that Sam was using the exchange as a slush fund for a lot longer than even I suspected. Just to give you one example, witnesses have testified that the exchange took a giant loss of hundreds of millions of dollars on something called MobileCoin. And so, had the exchange revealed that loss, it wouldn’t have been able to keep raising venture capital and users might have lost confidence in it and pulled their money. Instead, the loss was shunted secretly to the hedge fund Alameda, which was able to withstand any sort of financial hit because it was borrowing the user funds.

So, just like right there, the exchange wouldn’t have been a good business absent this Alameda relationship. From the start, this crooked relationship between the exchange and the hedge fund was essential to the exchange’s operations. Sam made all these claims about the exchange’s top-notch risk management practices. He was testified before Congress that FTX had this great risk management system that was so amazing that it should be adopted at other exchanges, and that was just totally made up.

So, I don’t think that it’s really true that the exchange was a good business, and that’s setting aside the fact that it’s a crypto gambling casino to begin with, even if it’s a good one.

Robinson

So essentially, if Sam Bankman-Fried had not lied about everything that his business was doing, and the things that he said were true, then he would have had a good functional casino. But that’s about all you can say.

Faux

Yes. If he was not a giant liar who ran a massive fraud, he would have had a casino where you could go gamble and lose your money on a bunch of dumb coins that were scams run by other people.

Robinson

I don’t want to speak ill of your colleague, Matt Levine, but I was kind of shocked how long it took him to start to be dubious that Sam Bankman-Fried was insincere. He has a quote, rather a long way into the timeline, where he said, I still think Sam Bankman-Fried meant well. [In Nov. 2022, Levine said he found Bankman-Fried “likable, smart, thoughtful, well-intentioned, and candid.”] Sam Bankman-Fried did not, in fact, mean well.

What about you? Where was the point where you thought, this is not an effective altruist trying to do good, and gosh, he’s just not that good with spreadsheets?

Faux

I would have to go double check what Matt has said more recently, but I may be pretty close to Matt Levine on this, which is that as soon as FTX failed, it was pretty clear to me that fraud had occurred and that Sam had done it. The $8 billion was gone, and it didn’t really make any sense that it could be gone without fraud. It didn’t make any sense that it could have been done under Sam’s nose when he’s obsessed with money. He’s very smart, and he was definitely keeping track of how many billions of dollars the exchange had and how much the hedge fund had.

But in terms of Effective Altruism, I still think that Sam was motivated by this idea that he was somehow going to save the world. I think that is what actually made him very dangerous.

Robinson

You mean like megalomania?

Faux

Yes. So, let’s say they had a choice: should we cover up this loss at the exchange and dip into customer money? The logic would be, yes, we should because if we don’t, the exchange might fail, and if we do it, maybe we’ll soon be trillionaires and that’s going to help us fund research into safe AIs and maybe one day we’ll prevent a Terminator-type scenario.

So, I think the ends definitely justified the means, no matter how fraudulent those means were. And nothing at the trial has come out to say that these people didn’t believe in Effective Altruism. But definitely a lot of stuff has come out about megalomania. Caroline Ellison is Sam’s ex-girlfriend and colleague who ran the hedge fund arm, and she testified that Sam believed there was a 5% chance that he would become president. The lawyers asked, of what? And she said, “Of the United States.” It was a very good moment in the courtroom.

Robinson

Wasn’t there a quote he gave to Vox, though, where he seemed to suggest that he didn’t believe in any of this stuff?

Faux

Yes. And this is where you might say I’m an SBF apologist here. So what he said is that he didn’t believe in business ethics, or he said, fuck the SEC, or something like that, too. He said he didn’t believe in this ethical stuff. He had sometimes said in interviews that even though he was a utilitarian—an ends justify the means kind of person—I know I need to follow the rules, I wouldn’t want to break any laws, and securities regulation is important. I think those were lies. “I’m a hardcore utilitarian, who only believes that we should judge outcomes by what’s going to have the greatest good for the greatest number of people.” He was pretending to have a more normal sense of ethics.

Robinson

To an ordinary human being with an ordinary sense of ethics, a number of the ways in which he lived his life and made decisions strike one as bizarre. He lived in accordance with this code of “expected value,” which is the probability that something will go well, and it seemed to lead him to take extraordinary risks. He said something like, I would do something that had a 50% chance of destroying the world if it also had a 50% chance of doubling the amount of happiness in the world or something like that.

Faux

If it were 50/50, he wouldn’t do it; but if it was a 51% chance to double how good the world is, and 49% the world ends, then he would do it—to your point. But the thing that doesn’t really make sense about his logic is, if you keep flipping a coin, it will eventually land on tails, like it did for him. He kept flipping these coins, and eventually something bad happened. Now he’s on trial for fraud and facing decades in prison. What did he think was going to happen? That he was just going to go on this epic streak of flipping coins and landing on heads and eventually be a trillionaire and save the world? I think maybe that is what he thought. I don’t know. I wish we could have had a more honest conversation about this.

Robinson

I think you mentioned that he believed that sleep was inefficient time, so he couldn’t sleep because the value of being awake was too high. But then he seemed to play video games all the time. And I’m thinking, how do you justify that in terms of “expected value”? It’s video games. Did he have a theory of why he should play video games?

Faux

I think he would have said that doing publicity was very important, so he had to do a lot of interviews with different publications to build FTX’s profile, which I think is fair—all the good publicity really helped build it up—but that doing interviews was very boring, and he needed to play video games while doing them to stay engaged. But you’d think there’d be some value in just paying attention, you might get better answers. For example, I’m not playing video games right now.

Robinson

He also doesn’t believe in reading books. Many things that we think might be important, like learning from books or listening to people, he has theories for why they’re not actually valuable.

Faux

Yes, there was a good one—this is from the Michael Lewis book, I think—but he tried to argue that there’s no way that Shakespeare is actually good because just statistically, it’s so unlikely that the greatest writer would be born at a time when the world’s population was much smaller and there are many fewer writers, which is just totally illogical. Shakespeare’s works are published now, we can just judge whether they’re good or not by reading them. It’s not a statistics problem.

For me, it starts to take you into some like really weird places right away. One of the first times I spoke with Sam, we had this conversation where I was very close to understanding his game, but totally struck out. I said, the greatest good for the greatest number of people: doesn’t that mean it would make sense for you to just steal as much money as you can from these crypto people and give it to poor people? Right now, you have so much credibility. They all love you. I bet you could steal like $5 billion—it wouldn’t be that hard—and we could buy so many mosquito nets. That’s a big Effective Altruism cause. We give everyone a mosquito net.

And he gave this answer about why the charities don’t want your dirty money and how he can make more money running an honest business. It was a good question. I wish I had stuck with that reasoning a little longer.

Robinson

He said, of course it would not pay off to steal all the money and use it to do good. But it turns out that that might have been the case.

Faux

Yes, and the reason I believed him, or I saw some logic of what he was saying, is because FTX, which I thought was an honest business, was valued at $32 billion, and that was more than I thought he could steal running a scam. I thought, it doesn’t pay to scam, just keep running your exchange.

However, the exchange was the scam. That was what I was missing.

Robinson

While I have the opportunity of asking you about this stuff, I have to ask you about the Ape people because you got up and personal with them. This is one of the parts of the story that fascinates me the most. During the middle of what was called the NFT craze, people—well, it’s not even clear that they were buying images of apes, they were buying code, essentially—but people would spend a lot of money on something that was very close to an image of a cartoon ape. And by a lot of money I mean a lot of money. And you even did it yourself, although for sound reasons.

What was going on there? It just baffles me.

Faux

We’re talking about NFTs—non-fungible tokens—which was kind of my favorite part of this whole cryptocurrency mania because it’s so weird. You can go look at promotional stuff about NFTs now, and it’s hard to believe it was just a year or two ago that we had Paris Hilton on the Jimmy Fallon show, pulling out an ugly cartoon of an ape and saying, this is my Bored Ape. Supposedly, she paid $400,000 for this.

The idea was that these Apes lived on the blockchain, and that somehow this meant they were the future of art, and that you were getting in early on the next Disney or the Lucasfilm. It’s a weird thing where people like you and me, even in the moment, probably would have been making fun of the Bored Apes like many people were, but enough people bought in that the prices went to these crazy levels. Within a few months of these Bored Apes being created, they were being auctioned at Sotheby’s. I think that shows something about art auction houses as well. Because the Ape people love to point to these things as great proof that the apes are credible. They’ll say, “it’s auctioned at Sotheby’s.” No, they’ll probably auction anything if it gives them a commission.

Robinson

It would seem that way.

Faux

Or I like this one: one of the Apes got represented by CAA, the Creative Artists Agency. I am also represented by CAA, so you know they’ll take anybody. But I wanted to go see this Ape thing for myself. They had a big party in New York, ApeFest, and you had to buy one to get in. I just thought, you know what, I’m going to do it. I got to know what’s happening inside ApeFest. I can’t write this whole book about crypto and not go to ApeFest.

And like so much about crypto, it was even dumber than I had imagined.

Robinson

I don’t want to tell our readers how much you spent on your Ape, either.

Faux

It was a lot more than I was comfortable with. I knew I wouldn’t like spending that much on an ape, and once I did, I really didn’t like it. I couldn’t sleep. I was waking up at like four in the morning. And there was a funny part, which is that I wanted to check the Ape prices to make sure they hadn’t collapsed.

But I’d read all these things about people who have the apes getting hacked, and their ape being stolen, and I’m thinking this is true. The more I click on stuff, the more likely it is that I get hacked, and if I don’t click at all, it’s harder to be hacked. So, I’d wake up, and I’d think, I really want to check the ape prices, but if I go to these websites, I’m going to get hacked and lose my ape. It was terrible. I only held it for three days. That was all I could handle.

Robinson

Anyway, I believe you were about to tell us what ApeFest was like.

Faux

We had Snoop there. We had Eminem there. It was better than most crypto conferences. Nobody cried—oh, wait, a guy cried. He had purchased or won a rare potion, and the Ape cartoons can consume the potion, and this creates a mutant Ape. It was such a big deal; this was like the last mega mutant potion, which is really special. Somebody sold for $5 million. So, this guy had consumed the mega mutant potion live at ApeFest, and I think that he did cry when he saw how his ape mutated on the big screen. So I can’t say that no one cried.

But mostly it was a bunch of guys who were just really drunk and stoned, standing around listening to Snoop rap about ApeCoin, the official coin of the Bored Apes.

Robinson

I guess you have some insight into the psychology of someone who spends this amount of money on this. It’s not any clearer to me after reading your book. It’s not even obvious what they’re buying for the $5 million. Because when you say “the Ape drinks the potion” or whatever, does that just refer to like an animation of that happening? How do you “own” that? It’s not really to do with copyright. It’s very, very strange what you’re actually getting for your giant pile of money. Explain to me the psychology of the people who pay all the money for the apes.

Faux

There’s an explanation that kind of makes sense. Crypto people, even people who like crypto, sort of know it’s all a game. Not everyone is like this. But there’s a group of crypto people who know it’s a game. They know, essentially, it’s a pump and dump scheme, and you’ve got to get in early and sell while the selling is good and get out before the whole thing collapses. They’ll buy some random new coin, and they’ll even call it a shit coin. They’ll say, I’m like a veteran shit coiner, and that’s why I’m buying Dogelon Mars, or [HarryPotterObamaSonic10Inu], which is a real one that did pretty well recently.

These people will say that these NFT collections are basically shit coins with pictures. They’ll say, I’ve seen that happen before: before Bored Apes, there was CryptoPunks. Now, everyone thinks NFTs are a thing: I’m going to buy my Bored Ape, get in early, and it’ll be the next CryptoPunks. I see there’s enough chatter on Reddit, and I see celebrities are getting involved. I just think it will keep going a little bit longer, and I’ll be the one who makes money. But it’s a zero-sum game, and whatever money you make has to come from some greater fool. It just can’t keep going forever. And it hasn’t. Bored Ape prices, amazingly, are down 90%, not 100%.

Robinson

Considering what it is.

Faux

Yes, it still costs 50 grand to get one of these Ape cartoons. And like you said, you only really own a receipt on the blockchain that proves to other people who are conversant in blockchain that you own this Bored Ape. And I ran into this problem when I tried to brag to my mother about my Bored Ape. I sent her a picture of it and said, look at this mutant ape I just bought. And she sent it right back to me, because on the iPhone, there’s a little button that shows download the image. And she asked, how do you own this Bored Ape? And I thought, alright, mom, the blockchain proves that only I own this Bored Ape and not you. But it would take me half an hour to explain it, you probably wouldn’t follow, so just trust me. You don’t own the Bored Ape. It’s mine!

Robinson

And it doesn’t really prove it if you don’t accept the kind of mental framework that says that that is what ownership means.

Faux

Yes. So, one of the big pitches by the Ape enthusiasts is that you are buying valuable intellectual property. Firstly, the blockchain is not legal, so it’s questionable whether the intellectual property conveys with your purchase on the blockchain. But then there’s another problem, which is there are thousands of Bored Apes, and they all basically look the same. Even if Bored Apes became really, really popular, they’re not going to make a movie based on each Bored Ape; there will not be 10,000 Bored Ape movies. There’s not going to be 10,000 variations of the Bored Ape t-shirt, each one that sells really well.

So, this idea that you’re buying really valuable Bored Ape intellectual property was ludicrous on many levels, but that didn’t stop Yuga Labs, the creators of the Bored Apes, from raising venture capital at a $4 billion valuation, which is similar to Lucasfilm, which actually owned the Star Wars IP, which is actually popular. Nobody cares about Bored Apes. It was just for a couple of years, there was a lot of money to be had if you wanted to pump out some crypto coin or NFT collection.

Robinson

What makes sense to me is people who are just in it for the money, who see the money going up, is that, essentially, they see themselves as operating in a casino. They think, if I pay this now, I get this thing, and I can pass it off to someone else. What strikes me is totally bizarre is anyone who sincerely believes that they’re getting anything for their money and not in that kind of game.

Faux

I think when they see big name celebrities and famous venture capitalists playing the game with them, they think, “this is a pretty legit game.” They know they have a friend who made a lot of money playing a similar game, so why not me?

But I’m with you. I really want to know who’s buying Bored Apes now. What kind of person is thinking, “It’s coming back, I’m getting a discount Bored Ape for $50,000 right now.” I think what we also aren’t talking about is that in any market where there are so few items—10,000 is a very small number of items compared to a company that has millions of shares of stock—it is easier to manipulate the market.

For example, one of the things that Alameda Research invested in with the money they borrowed illegally from customers was Yuga Labs, the creators of Bored Apes. They invested about $50 million, I think, in Yaga Labs. Since then, it’s been revealed that they also likely were the buyer of this big lot of Bored Apes at auction at Sotheby’s. They had paid something like $25 million for some rare Bored Ape. So, there were people who had a vested interest in making this work, who were buying at high prices, maybe hoping that would get others to come in.

Robinson

I always wondered that. When I saw someone paying $650,000 for an image of a yacht in a fake Metaverse thing, I thought, is this like a fake transaction designed to get a headline that says, “Image of yacht sells for $650,000,” so that the people who have designed this thing can sell other things because now it’s in the news that this is selling? I don’t know if Paris Hilton actually paid that much money for the Bored Ape, or was actually given one for free. But it strikes me that there’s a lot of incentive to create fake transactions to precipitate real transactions.

Faux

A million real dollars or 500,000 real dollars is a lot of money. It would make sense for us to run a really elaborate scam with tons of fake transactions and fake Twitter accounts and fake chat rooms, all just to lure one sucker and make a $500,000 profit. So, it totally makes sense.

Of the celebrities who endorsed Bored Ape, a lot of them have been sued by class action lawyers who are trying to blame them for the price collapse and recoup money for investors. So at this point, everyone involved has denied that celebrities got free Bored Apes, and some of those celebrities were invested in the company. I actually sort of like this idea, and this is just conjecture here, but there may have been a double scam where, first, you trick celebrities into investing in your dumb Bored Ape company—a lot of celebrities are probably not very good at math—then you convince them that it would be good for their Yuga Labs investment to buy a Bored Ape for $400,000. You get them on both ends. I like it better if the celebrities actually did pay.

When I was at ApeFest, I heard Jimmy Fallon, a Bored Ape owner, talking to one of the creators of the Bored Apes, and he said something like, “You should write a book about this one day.” And I’m thinking to myself, if they were really honest about how this all went down, I would love to buy that book. These guys are smart dudes, it seems like. They’re into literature—one of them worked for a publishing company and was just following along with this crypto stuff, and one day they’re like, how about we make Bored Apes? And they just hired some artists just to make these cartoons, and within a few months, they’re like on top of the world. When they created ApeCoin, I think they were billionaires on paper—I don’t think they actually turned that into real money. It’s one of my favorite stories from this whole crypto bubble. If they would really come clean about what that all felt like and how it all played out, I’d love to read it.

Robinson

You talked to Jimmy Fallon briefly at this thing, didn’t you?

Faux

Yes. So, at the time I’m at ApeFest, the Ape prices had recently fallen. Pretty much anyone who was there had lost a lot of money, but you still could be ahead if you got in early. It was very influential when Jimmy Fallon had Paris Hilton on, and they showed off their Apes on the show. I think it gave the whole thing a big boost in credibility. And now, here are people losing real money.

So, I saw Jimmy Fallon off towards the back in the VIP area with some bodyguards. I walked by and flashed him my mutant Ape, and like everyone else at the party, he pretended to be interested because we’re all part of this club together, but we don’t really care because all the Apes look the same. I said, “You’re promoting this thing, I think it was pretty influential, and now people have lost a lot of money. How do you feel about that, Jimmy Fallon?” And he said something like, “Oh, I’m not an investor, I did it for the community,” which is just kind like a catchphrase with these guys.

And I’m thinking, first of all, you’re in the VIP section—you’re avoiding the community. Second of all, the community is like a bunch of drunk dudes who are just standing around and have nothing in common. Besides, we all paid ridiculous amounts of money for these dumb cartoons, which is not a great form of community building.

So, I thought that was a pretty ridiculous answer from Jimmy Fallon.

Robinson

Just to conclude here, what lessons can we take from the wild ride taken in your book? As you say, it took you across multiple continents, you saw this thing rise and fall, and it seems absurd in many ways. What should the reader takeaway in terms of insights into the human condition that came from this adventure?

Faux

At least for me, I am not always that confident that I’m the smart one in the room, or that I know something. I kept thinking, all these smart people are doing crypto stuff, there must be something to it; if it doesn’t make sense to me, I need to keep studying up.

And what I realized was, I’m glad I did look into it thoroughly because I was able to go back and write this book, but maybe sometimes you should just trust your instinct, and if something seems too good to be true, maybe it is. If you don’t get something that doesn’t make sense, put it back on the person who’s trying to sell it to you and say, if you can’t explain this to me better, I don’t think there’s anything to it.

But FOMO is powerful, and I can’t say for the next big thing that comes around that we’re all not going to want to miss out on that one, either. So, I’m not sure if society will have the power to resist the next mania.

Robinson

I like that. That’s an empowering and somewhat egalitarian bit of advice there that suggests that ordinary people should be confident in their ability to understand things. If you don’t understand it just because it is confusing, and the people offering it present themselves confidently as if they’re intelligent, it does not mean that they are intelligent. And if someone says to you, as Alex Mashinsky said to you, “either the bank is lying, or I am lying,” they could just be lying!

Faux

Yes. I think we all knew the answer to that one as soon as it left his mouth, but it was somewhat nice to see that finally it caught up with him, and he got arrested.

Robinson

Although the crazy thing is that the one cryptocurrency that you were so skeptical of throughout the book, this Tether thing, as far as I can tell, still has not collapsed even though it’s incredibly shady. Is that right?

Faux

Yes, it’s doing great. When I started out, I thought, how did these crazy dudes get $50 billion? Now they have $84 billion. Almost every other big company in crypto has collapsed, and they’re still standing. And if you believe their numbers, Tether is one of the most profitable companies in the world. They make more profit than Nike. And it’s run by like this weird former plastic surgeon from Milan, dreamed up by this child actor from the Mighty Ducks, and now they’re just making like a billion dollars a quarter. I have no inside information here, but I don’t think it’s the end of the story. I’m saving room in the paperback for new developments.

Transcript edited by Patrick Farnsworth.