A Brief Cultural History of the White Rapper

Why do they exist? Where did they come from? Can they be defended? The most pressing questions, answered.

Rap music, as you may have heard, celebrates its 50th anniversary this year. In five decades, the genre has produced a dizzying variety of artists and styles: there’s gangsta rap, mumble rap, horrorcore, crunk, drill, trap, and a dozen others. From DJ Kool Herc to the latest Drake album, it’s a rich history. But in the whole pantheon of rappers, there’s one figure who fits awkwardly among the rest. One whose very existence is politically charged, and whose evolution can tell us a lot about the dynamics of race and racism in the United States. The odd man out, the black sheep: the white rapper.

Like jazz and the blues before it, rap music is undeniably Black. Its creators were working-class Black men performing as DJs in New York City circa 1973, and its greatest songs—tracks like N.W.A.’s immortal “Fuck Tha Police” or Kendrick Lamar’s “Alright”—are explicitly about African American struggle and protest. But in those early years, white rappers emerged, too. It’s difficult to know who the first one actually was; technically it could be Debbie Harry of Blondie, who rapped on 1980’s “Rapture,” or even Rodney Dangerfield, who dropped the deeply weird novelty single “Rappin’ Rodney” in 1983. (Seriously, Google it.) The Beastie Boys charted with Licensed to Ill in 1986, but they were a hybrid act, equal parts punk rock and hip-hop. 3rd Bass were competent but obscure. Truthfully, the white rapper didn’t really arrive as a cultural force until 1990, with the advent of one Vanilla Ice—and it was there that the problems began.

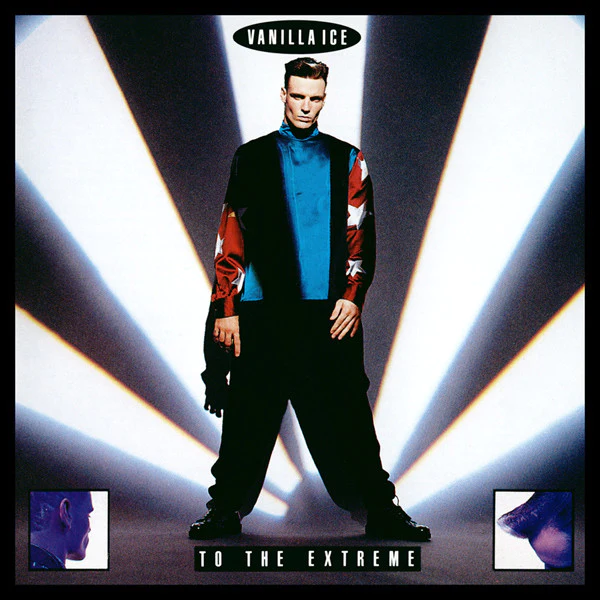

From our vantage point in the 2020s, it’s hard to believe just how ubiquitous Vanilla Ice was at the height of his fame. As music journalist Jeff Weiss recalls in his definitive profile for The Ringer, Ice wasn’t just a rapper; he was a multi-media empire, briefly eclipsing even the popularity of M.C. Hammer. He had his own board game, performed the “Ninja Rap” in Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles II, and reportedly turned down a marriage proposal from Madonna. His signature hit, “Ice Ice Baby,” was everywhere. His debut album To the Extreme reached No. 1 on The Billboard 200 album popularity chart and raked in more than 10 million worldwide sales in its first six months. But his moment in the sun was short-lived, lasting roughly 12 months. By the end of 1991, Vanilla Ice was synonymous with corniness, the butt of a scorching Jim Carrey parody song called “White, White Baby.” His Hollywood debut, Cool as Ice, was nominated for seven Razzie parody awards, including “Worst New Star” and “Worst Original Song,” and its opening track “Cool as Ice (Everybody Get Loose)” peaked at 81 on the charts. He’d officially crashed and burned.

So what went wrong? What made Vanilla Ice so legendarily corny? It wasn’t lack of skill; even today, Ice is a perfectly decent rapper on a technical level. Part of it was the huge hair and the spangly costumes, which Weiss describes as “Captain America meets Aladdin.” Part of it was the nakedly commercial nature of the whole phenomenon and all those spin-off products. But the core problem was one of authenticity, or lack thereof. Vanilla Ice’s hastily-ghostwritten 1991 autobiography, Ice by Ice, claimed that he grew up in and around Miami and went to the same high school as Luther Campbell from 2 Live Crew. However, curious newspaper reporters soon discovered “numerous contradictions” in this supposed life story. Ice’s birth name, it turned out, was Robert Van Winkle (which is about as white as you can get), and he was actually from a suburb of Dallas, Texas, not Miami. Confronted, the rapper insisted the offending lines were put in the biography without his knowledge, and that he hadn’t actually lied, as such. As he told Weiss in 2020:

“I was embarrassed to tell people I was from Farmers Branch. I didn’t tell them I was from Miami. I didn’t tell them I was from anywhere. I was just like, ‘Listen, I’m from around the corner, man. I’m from around the fucking way.’ I actually tried to detour people.“

On top of the questionable origin story, there were also allegations that the beat for “Ice Ice Baby” was a ripoff, copying the bassline from Queen and David Bowie’s “Under Pressure” almost identically—an issue the rapper opted to settle by buying the rights to “Under Pressure” itself. Between the two issues, though, the damage was done. Whatever his intentions, the public saw Vanilla Ice as a fraud, a white guy cynically and disrespectfully using rap as a way to get rich. Or as Carrey put it on “White, White Baby”: I’m white, and I’m capitalizin’ / On a trend that’s currently risin’ [….] I’m livin’ large and my bank is stupid / ‘Cause I just listen to real rap and dupe it.

All of this is more serious than it seems, and it’s bigger than one white guy making a fool of himself. The Vanilla Ice debacle has to be understood in the context of American racism and white supremacy and the nasty history of white people co-opting Black artistic forms for their own gain. The most well-known example of this came with rock ‘n’ roll, where white artists—most notably Elvis—became rich and famous using songs and styles originally created by Black artists, who remained on the outside looking in. By the 1980s, white rock bands were the rule, and Black ones the rare exception. Jazz managed to avoid being whitewashed in the same way, but there’s still something a little suspect about Kenny G being its all-time best-selling artist. In his biography of Eminem, Rolling Stone journalist Anthony Bozza writes that the concern among Black fans and critics that “a white, ‘safer’ version of hip-hop [would be] more attractive to white corporate advertisers, and may dictate future artist signings” was not unfounded. Vanilla Ice, with his raft of corporate sponsorships and licensing deals, only seemed to embody these fears. Hence the backlash.

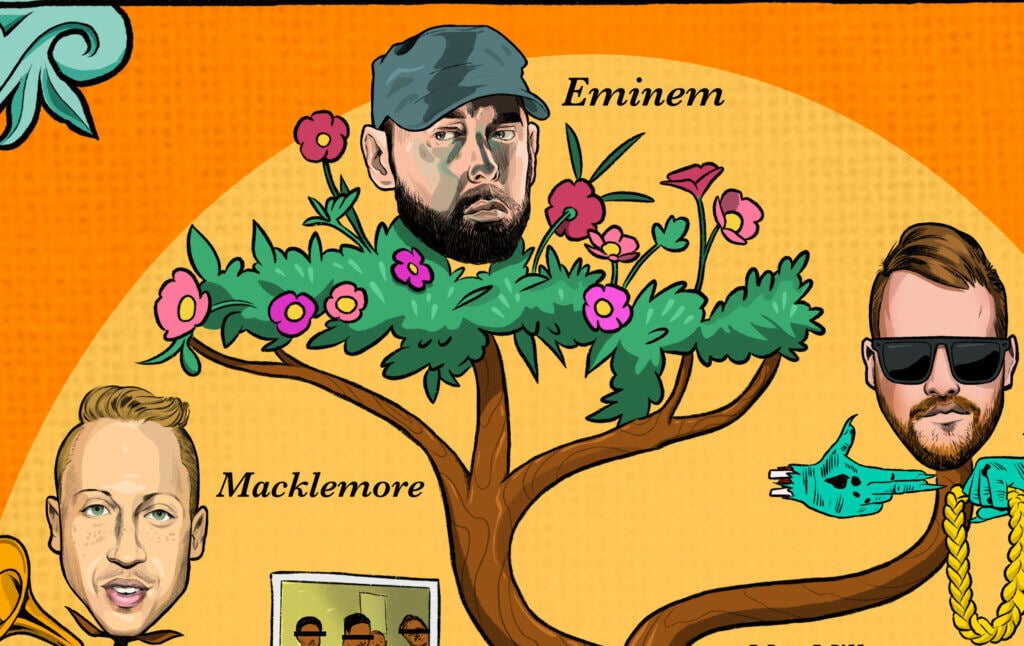

This leads to another interesting question, though: if Vanilla Ice is corny, with a distinct note of cultural appropriation to him, what makes Eminem different? Born Marshall Mathers III, Eminem was the next notable white rapper to emerge, and for most people, he remains the face of white hip-hop. Unlike Vanilla Ice, he has actually gained the respect of both hip-hop fans and his fellow rappers. He has collaborated with the likes of Jay-Z, DMX, Snoop Dogg, Busta Rhymes, and Nas and is ranked No. 5 on Billboard’s recent list of the 50 Greatest Rappers of All Time—the only white artist to even sniff the “GOAT” discussion. Clearly, something went right, but what?

Here, each artist’s approach to his economic class played a role. Growing up, Vanilla Ice wasn’t exactly privileged; as Weiss recounts, he dropped out of high school and scraped together a living as a busker and an entertainer in majority-Black nightclubs like Dallas’s City Lights. But to hear his lyrics, you’d never know it. By contrast, Eminem’s experience of poverty in Detroit is woven throughout his catalog, from 1997’s “If I Had” (where he’s “tired of havin’ to work as a gas station clerk”) to 2017’s “Believe” (where he “remember[s] the days of / minimum wage for general labor”). Bozza’s biography—which is worth a read, if a little hagiographic—is full of stories about a young Mathers working dead-end jobs, struggling to pay rent, and getting evicted over and over again, all while surrounded by drugs and violent crime. The difference between the two rappers is that Vanilla Ice had little interest in prodding the wounds of his past—at the end of the day, he was making party music—while Eminem brings an almost Dickensian focus to the subject. There’s remarkable similarity between, say, the experience of urban poverty Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five rapped about on 1982’s “The Message,” one of the first hip-hop songs to include explicit social and political commentary:

Broken glass everywhere

People pissing on the stairs, you know they just don’t care

I can’t take the smell, can’t take the noise

Got no money to move out, I guess I got no choice

Rats in the front room, roaches in the back

Junkies in the alley with a baseball bat

I tried to get away, but I couldn’t get far

‘Cause a man with a tow truck repossessed my car

And the one that Eminem details on 1999’s “Rock Bottom”:

I deserve respect, but I work a sweat for this worthless check

I’m ‘bout to burst this TEC at somebody to reverse this debt

Minimum wage got my adrenaline caged

Full of venom and rage, ’specially when I’m engaged

And my daughter’s down to her last diaper, it’s got my ass hyper

I pray that God answers, maybe I’ll ask nicer.

Despite the writers of these lines coming from two different racial backgrounds and two distinct decades, it’s recognizably the same economic hardship they’re struggling against. And that, in turn, suggests that white rap needn’t be an embarrassing form of cultural appropriation. In the right hands, it could be a vehicle for cross-racial solidarity between poor and working people of all races. When nobody has a dollar to their name, distinctions matter less.

What’s more, Eminem was acutely aware of the Elvis comparison and the issue of white theft of musical forms. He shouts it out and takes a tongue-in-cheek responsibility on his 2002 megahit “Without Me” (I am the worst thing since Elvis Presley / To do Black music so selfishly / and use it to get myself wealthy, hey!) and more recently on “The King and I” (I stole Black music, yeah, true / perhaps used it). But he also has a counter, and it’s a good one. Unlike the white artists who “stole” rock ‘n’ roll, Eminem is always shouting out his inspirations and giving the progenitors of rap their due respect. On “’Till I Collapse” (yet another collaboration, this time with vocalist Nate Dogg), he gives his own idiosyncratic version of a “top rappers” ranking:

I got a list, here’s the order of my list that it’s in

It goes Reggie, Jay-Z, 2Pac and Biggie

André from OutKast, Jada, Kurupt, Nas, and then me

But in this industry I’m the cause of a lot of envy

So when I’m not put on this list, that shit does not offend me

In a genre built on braggadocio, where it’s practically expected for artists like Lil Wayne to thump their chests and proclaim themselves “the best rapper alive,” Eminem names himself the ninth best and puts eight Black men ahead of him. The verse can read as a humble-brag, but it’s also a valuable history lesson for listeners who may not be familiar with all these names, and it serves to prevent that history from ever being erased. Even when he is bragging about his skills, on 2013’s “Rap God,” there’s another multi-bar tribute:

Me? I’m a product of Rakim

Lakim Shabazz, 2Pac, N.W.A, Cube, hey Doc, Ren

Yella, Eazy, thank you, they got Slim

Inspired enough to one day grow up, blow up and be in a position

To meet Run–D.M.C., and induct them

Into the motherfuckin’ Rock and Roll Hall of Fame

This time the message is even more explicit: there would be no Eminem without this legacy, and the listener had better remember it. He’s not a replacement for Black rappers, but a grateful student. Can anyone imagine a white rock star stopping in the middle of a song to deliver six lines about how cool Chuck Berry is?

From that second list, one name stands out: “Doc,” aka Dr. Dre. One of the founding members of N.W.A., Dr. Dre discovered Eminem at a time when his debut album, “Infinite,” had flopped—and according to Bozza’s biography, he “saw suicide as a viable option”—and signed him to his fledgling label, Aftermath Records. For more than 20 years, the two have worked closely together, and when Eminem references Dr. Dre in a verse, it’s always with profound loyalty and respect. Just look at Eminem’s lines on the song “I Need a Doctor,” from Dre’s 2011 album Compton, which he was featured on:

And I don’t know if I was awake or asleep when I wrote this

All I know is, you came to me when I was at my lowest

You picked me up, breathed new life in me, I owe my life to you

But for the life of me, I don’t see why you don’t see like I do

[…]

It was you who believed in me when everyone was tellin’ you

Don’t sign me, everyone at the fuckin’ label, let’s tell the truth

You risked your career for me, I know it as well as you

Nobody wanted to fuck with the white boy

Dre, I’m cryin’ in this booth

This is fascinating, and transgressive, on a lot of levels. In the first place, it’s unusual for a rap song to display this much emotional vulnerability. With rare exceptions, male rappers don’t admit to crying, especially over their relationships with other men. (In a groan-inducing moment, Dr. Dre feels the need to drop a homophobic slur in his replying verse, as if to prove that there’s nothing gay going on.) But the racial dynamic is also important. Dr. Dre is not just a collaborator, but a mentor, and one of the most important people in Eminem’s life—almost a surrogate parent. The theme constantly recurs, as recently as 2018’s “Kamikaze” (Which is why I identify with the guy / who I was invented by, Dre’s Frankenstein.) And the whole relationship is made possible by Dr. Dre’s willingness to look past racial differences and embrace “the white boy.” It’s this, above all, that makes him worthy of Eminem’s admiration. For a gifted white artist—blonde-haired and blue-eyed, no less—to look up to a Black man in this deeply personal way is anathema to the logic of white supremacy. For anyone with a racist worldview, it’s practically a slap in the face.

That last bit isn’t speculation, by the way. In August 2023, a white supremacist mass shooter named Ryan Palmeter took the lives of three Black people in Jacksonville, Florida and left a manifesto behind. In its pages, Palmeter wrote that he also wanted to kill Eminem. Specifically, he said (warning, this is disgusting language) that the rapper “walks the edge between n— lover and honorary n—,” and that “Total N— Death” would include him “as a valid target and he is to be killed on sight.” He also wanted to shoot Machine Gun Kelly, another white rapper, for similar reasons. Now, obviously this is disturbing. But if you can judge a person by the enemies they make, Palmeter’s hatred is also a badge of honor for both musicians. It was their embrace of, and respect for, Black culture that the shooter’s deranged belief system couldn’t abide.

Unfortunately, not every white rapper pulls it off gracefully. For every good one, there’s at least two or three who are varying degrees of embarrassing. We’ll gloss quickly over the escapades of Marky Mark and the Funky Bunch, as Mark Wahlberg would probably like everyone to forget the group ever existed. Asher Roth is notable only for his debut single “I Love College,” which kicked off the regrettable trend of rap songs about being in a fraternity. Yelawolf, an Eminem disciple from Alabama, quickly learned why it’s not a good idea to use Confederate flag imagery, even if you think you’re being all post-racial and reclaiming it. NF is a Christian who raps very fast and never swears, which is presumably nice if you’re into that kind of thing. G-Eazy is just terminally bland. And then there’s Macklemore.

In a lot of ways, Macklemore is a perfect time capsule of the Obama years. He’s the epitome of the earnest white liberal, always going to great lengths to let you know his heart’s in the right place. One of his breakout hits, “Same Love,” is a gay-rights anthem, which is a welcome development in a genre that’s often been extremely homophobic. But it’s a somewhat self-centered one, starting with the unintentionally funny line, “When I was in the third grade, I thought that I was gay,” before taking a few bars to make it clear that Macklemore is not in fact gay, and then getting into the actual subject of gay rights. Compared to more recent songs by rappers like Lil Nas X—whose approach is simply to be extremely gay, and make no apologies for it—“Same Love” comes across as preachy and self-important despite its good intentions. This is a very white problem to have.

Like a lot of liberal-minded white people, Macklemore also struggles to treat the subjects of class and poverty with the seriousness they deserve. His most popular song, “Thrift Shop,” is all about the joys of picking up strange vintage items—Velcro sneakers, a “velour jumpsuit,” a “dookie-brown leather jacket”—secondhand from charities like Goodwill and wearing them out to nightclubs, making everyone gawk at the unique style. It’s a fun, poppy song, and there’s some good criticism of the fashion industry in there, with Macklemore making fun of would-be swag-havers who spend “fifty dollars for a T-shirt.” But there’s a darker side too. In real terms, the song’s protagonists are middle-class people slumming it, shopping at thrift stores as a form of entertainment and not because they actually need to. Historically, though, these stores have been a lifeline for people dealing with poverty, with some sociological studies finding that “thrift economies” play an important role in “mitigating difficult economic circumstances” like a major employer in the community closing down. In this light, “Thrift Shop” seems flippant about the possibility of taking resources away from the desperately poor just to use them for style points. Macklemore even frames thrift shopping as a for-profit enterprise—“I could take some Pro Wings, make ’em cool, sell those”—and says there are some items he’s too good for, “passin’ up on those moccasins someone else has been walkin’ in.” Since the song came out in 2012, there’s been a noticeable uptick in social-media influencers “thrifting” to resell clothes on apps like Depop, driving prices up in the process, and posting videos of huge “thrift hauls” containing more clothing than anyone could reasonably need. It’s gentrifying behavior, conducted largely by white people in a country where poverty disproportionately affects African Americans, and while Macklemore isn’t solely to blame for the practice, he did give it a catchy theme tune.

The real controversy, though, came when Macklemore’s The Heist, the album “Thrift Shop” and “Same Love” appear on, won the 2014 Grammy for Best Rap Album. It’s not that The Heist is necessarily a bad album, as such; it’s just that two of Macklemore’s competitors that year were Kanye West’s Yeezus, arguably his last truly innovative project, and Kendrick Lamar’s good kid, m.A.A.d city, one of the most compelling rap concept albums of all time. For reference, imagine the latest Ant-Man movie winning an Oscar over particularly good dramatic films from Denzel Washington and Morgan Freeman. It was pretty obvious that both race and capitalism were at work. The Grammys are, ultimately, a marketing event, and The Heist was a commercial, radio-friendly album, with a photogenic white face in all the videos. Compared to the dark, introspective stories of inner-city life on good kid, m.A.A.d city, or Kanye’s use of jarring industrial sounds and provocative song titles like “New Slaves,” Macklemore’s work was an obvious choice. The industry picked the album it believed would sell the most units, regardless of artistic quality, and poor Macklemore was left in an impossible position. He got branded a “culture vulture” on social media simply for having won, and then, when he wrote a very long text message to Kendrick Lamar apologizing for having “robbed” him, became a portrait of awkward white guilt.

White guilt is a recurring theme with Macklemore. He has not one, but two, tracks called “White Privilege” where he navel-gazes over his own whiteness, pondering what it means and how bad he should feel about it. The original “White Privilege” is innocuous enough, although it’s a bit weird that Macklemore chooses Aesop Rock—a Brooklyn rapper who, while white, is mostly known for using obscure words like “scholomance” and “susurrus,” and seems content to remain firmly underground—as an example of the genre becoming gentrified. On 2016’s “White Privilege II,” though, Macklemore looks on at a Black Lives Matter protest and can’t decide whether he’s allowed to participate or not:

In my head like, “Is this awkward?

Should I even be here marching?”

Thinking if they can’t, how can I breathe?

Thinking that they chant, what do I sing?

I want to take a stance cause we are not free

And then I thought about it, we are not we

Am I in the outside looking in,

Or am I in the inside looking out?

Is it my place to give my two cents?

Or should I stand on the side and shut my mouth?

No justice, no peace, okay, I’m saying that

They’re chanting out, Black Lives Matter,

But I don’t say it back

Is it okay for me to say?

I don’t know, so I watch and stand

This is, frankly, just pathetic. At the time, NPR’s Gene Demby panned the lyrics as “more than a little hamfisted,” writing that “Macklemore knows that people think he’s part of the problem, and we know he knows, and he knows we know he knows, ad infinitum.” Current Affairs’ chief film critic Ciara Moloney, meanwhile, criticizes the track for viewing antiracist protest “through a lens where Macklemore’s privilege calls for passivity,” noting that “Macklemore is worried about appropriating black activism, instead of realising that this fight should be his fight, too.” Both critiques hit the nail on the head, especially when you consider that, according to New York Times reporting in July 2020, “nearly 95 percent of counties that had a [2020 Black Lives Matter] protest recently [were] majority white, and nearly three-quarters of the counties [were] more than 75 percent white.”

If guilt is a paralytic, though, anger is a stimulant. It’s notable that, during the Trump years, several white rappers not named Macklemore had no trouble working out whether they were supposed to speak up against racism. They just went for it, and went in hard. For instance, El-P of Run the Jewels (a double act with Atlanta rapper Killer Mike) aimed a blunt warning at white racists on the song “Walking in the Snow:”

Funny fact about a cage, they’re never built for just one group

So when that cage is done with them and you still poor, it come for you

The newest lowest on the totem, well golly gee, you have been used

You helped to fuel the death machine that down the line will kill you too

Meanwhile, Mac Miller—who’d had his first Billboard hit with a 2011 track called “Donald Trump,” where he boasted that he’d “take over the world when I’m on my Donald Trump shit”—grew to loathe The Donald, calling him a “racist son of a bitch” and reworking the song to start with “Fuck Donald Trump” when he played it at concerts. Eminem, now in his late 40s, started doing loud, aggressive freestyles where he fantasized about beating up racist cops, bellowed that “this is for Colin!” (as in Kaepernick), and mocked Trump as a “racist 94-year-old grandpa,” threatening to “throw that piece of shit against the wall till it sticks.” (The Secret Service were not fans.) None of this was without flaw, but each rapper was trying—in their own unique way—to use their talent, their platform, and yes, their privilege, for good. They had an appropriate outrage at the bigotry growing around them and weren’t shy about saying so. For the white rapper as a political figure, this might be the most fundamental test.

The Eurockéennes de Belfort. Source: Wikimedia.

Not everyone passed it. There are also artists like Kentucky rapper Jack Harlow, who respond to conversations about racism and racial bias by getting weirdly defensive. On his most recent album, Harlow devotes an entire song, “It Can’t Be,” to complaining that anyone thinks his race might have something to do with his commercial success:

It must be my skin, I can’t think of any other reason I win (Ooh)

I can’t think of an explanation, it can’t be the years of work I put in

It can’t be the way that I stuck with the same friends

It can’t be the swag I got when I walk in, it can’t be

It can’t be the way I treat people or how I make time to see people

Or make sure that they feel like we equals

It can’t be the smile, it can’t be the eye contact with these crowds

It can’t be my pen, it can’t be these verses

This goes on for a while. And, sure, it could be those things. But plenty of Black rappers put in years of work, treat people well, and have swag and don’t make $5 million a year and host Saturday Night Live, as Harlow has. And it definitely isn’t the unique style Harlow brings to the table. In the past, other white rappers had something that set them apart, from Eminem’s cartoonishly violent imagery (often directed, unfortunately, at women) to Aesop Rock’s thesaurus-like vocabulary. But Harlow’s actual rapping can best be described as workmanlike. He’s never actively bad, but he’s definitely chasing existing trends rather than contributing something new. Specifically, rappers like Joe Budden and Machine Gun Kelly have criticized his style as an imitation of Drake’s, with MGK zinging him for being derivative: “I see why they call you Jackman, you jacked man’s whole swag / Give Drake his flow back, man.” Ultimately, it’s hard to tell which is worse—to fixate on white privilege, like Macklemore, or to splutter out angry denials that such a thing could exist.

Jack Harlow is a progressive icon, though, compared to the MAGA rappers. For the blissfully unaware, MAGA rap is a movement of mostly white rappers—the term “artists” does not apply—who rap about right-wing politics to the exclusion of all else. They started to appear around the time of Trump’s election in 2016 and have been growing like kudzu ever since. The most laughable is Forgiato Blow, the self-proclaimed “Mayor of MAGAville,” who recently went viral with the song “Boycott Target.” Or rather, he went viral for the music video in which he rolls around in a shopping cart like a giant baby, brandishing rainbow bottles of Stella Rosa and rapping about how the retailer is supposedly “targeting our kids” with Pride-themed merchandise. (Never mind that alcohol is, by definition, not for kids. Logic is not Mr. Blow’s strong suit.)

Some of his catalog is straightforward bootlicking, like “Trump Train,” “Trump Saved the USA,” “Trump Won,” “Trump Indictment,” “Vote Donald Trump,” and “Trap N Trump.” Other MAGA rappers break up the Trump worship with more general right-wing songs, like “White Lives Matter” by Mesus and the creatively-named “F Biden” and “F Biden 2” by Burden. There’s an endless amount of this stuff, most of it released directly to YouTube.

Forgiato Blow might be the first MAGA rapper; according to Gawker, he has been dropping Trump-related music since at least 2016. But their king is Tom MacDonald. MacDonald is by far the most popular figure in this wretched subgenre, with YouTube views routinely in the tens of millions, and he’s obsessed with his own whiteness. His 2018 single “White Boy”—not to be confused with the sequel, “Whiteboyz” with a Z—is one of the whiniest songs ever recorded. It’s four minutes and thirty-two seconds of Tom, blond dreadlocks flapping as he yells and jumps around, complaining about how white people are the real victims of discrimination these days:

Yeah, I’m white but I never put your neck in no noose

And I never burnt a cross or hid my face with a hood

You can’t just label me racist ’cause I’m related to people

Who did some terrible shit way back before I was alive

Keep in mind, no one had actually tried to label MacDonald racist at this point. They started doing that later, when he did things like—just to name a random example—joke that he was about to say “the n-word,” which turned out to be “nnnnew video Friday!” But he’s convinced that the world is out to get him specifically, simply for being white (and straight, a parallel obsession.) With each new song, the lyrics get worse, from “Snowflakes”:

He, she, his, him, hers, them, they

Screw a pronoun, ’cause everyone’s a r—rd these days

I hear ’em preaching at a protest that hatred’s the problem

But hating straight men, white folks, and Christians is common

To “Fake Woke”:

There’s a difference between hate speech and speech that you hate

I think Black Lives Matter was the stupidest name

When the system’s screwin’ everyone exactly the same

Yes, you read that right: in MacDonald’s world, everyone is getting screwed “exactly the same,” regardless of race! It’s not one particular race that keeps getting murdered by the police, or denied mortgages and medical care, or anything. It’s protestors who cause all the hatred in the world, and “straight men, white folks, and Christians” who suffer. The only thing missing is a song called “Respect tha Police” to make the picture complete.

There’s really no clever critique to be made here, no nuance to uncover. MAGA rap is exactly as stupid as it sounds. Tom MacDonald and Forgiato Blow are anti-artists, black holes of talent and creativity. They rap about conservative politics because without them, they’d have no ideas at all. Neither of them has produced an interesting beat, or rhymed an unexpected combination of words, in their lives, and they don’t need to. Their target audience isn’t even fans of rap, just conservatives with too much time and money on their hands who might spend a chunk of it on hastily churned-out, repetitive music. (Forgiato Blow, for instance, made more than half a dozen albums in 2022 alone, and he openly admits that they’re consumed by “people way older than me.”) For his part, MacDonald had a failed career as a mainstream rapper, releasing a 2014 album called “LeeAnn’s Son” where he talked about traditional topics like guns, sex, and gold chains. It went nowhere, and he transitioned into the more profitable MAGA lane soon after. It’s unclear how much of his own schtick he even believes, and how much is just pure grift. The whole thing is part of a wider effort by conservatives to create their own culture industry, from Daily Wire action movies to Tuttle Twins children’s books. Somehow, no matter how many times they fail, the conservatives in question never stop to consider whether there’s something about conservatism itself that makes creating truly bold, engaging new cultural works more difficult. They’re content to just regurgitate the same gruel forever and blame everyone else for not loving it.

The history of the white rapper is long and riddled with unfortunate missteps. At times, it’s enough to make you wonder if Caucasians should be banned from the genre entirely. But occasionally, there are gems to be found. Politically, the question of how to be a white rap artist is just an exaggerated version of a more familiar question: how to be a white American. If you are one of those, try to be an Eminem, a Mac Miller, or an El-P. If you’re going to participate in someone else’s culture, know what you’re doing, and pay your respects. Get angry when you see injustice, and don’t be afraid to get loud about it. But don’t make it all about you; don’t be a Macklemore. And please, dear God, don’t be a Tom MacDonald. One is already too many.