Why We Need Utopias

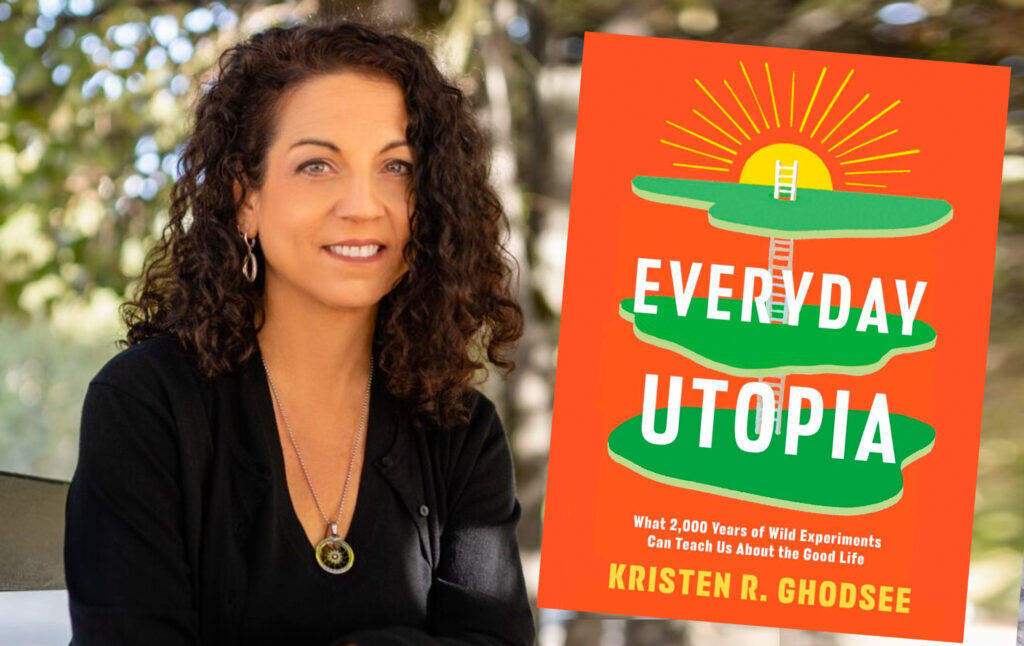

Kristen Ghodsee, author of “Everyday Utopia,” on what we can learn from experiments in alternative ways of organizing private life.

Kristen Ghodsee is Professor of Russian and East European Studies at the University of Pennsylvania and the author of books like Why Women Have Better Sex Under Socialism and, most recently, Everyday Utopia: What 2,000 Years of Wild Experiments Can Teach Us About the Good Life. Today she joins to explain why she believes utopian thinking, and studying the utopian experiments that people have engaged in across history, can help us figure out what life ought to be like and how to change the world for the better. From Charles Fourier to Star Trek, Ghodsee takes us on a fascinating tour of attempts to dream up and build mini-paradises. We discuss where utopias go right and where they go wrong.

Nathan J. Robinson

Let’s start with the word and concept of utopia. Many people are suspicious of utopias, and even see the word “utopian” as a pejorative or a negative descriptor of any particular plan. You say in your book that there is a “persistent and profound suspicion of political imagination.” So tell us, first, why “utopian” should not be a bad word.

Kristen Ghodsee

This is a really important question. In so many other aspects of our society, we tend to laud those who think outside the box, those who engage in what is sometimes called blue sky thinking. Like the old Apple computer fads in the 1990s—”Think different”—it’s the people who imagine the world differently who are the ones who are going to change it. In the boardrooms in corporations, and in academia and science, we really celebrate people who think different and outside the box, with no bounds to their imagination, but the minute we try to apply that thinking to our personal lives, or to our social problems, then it’s a terrible idea. It’s scary. It’s unrealistic.

I think that that’s a real problem. I think that the fact that we have limited our political imagination is part of what has gotten us into a kind of sticky mess right now in the early part of the 21st century, in terms of many social problems, including the pandemic of loneliness and isolation, and the sorts of inequality that are endemic—economic and gender inequality, racial discrimination, and all sorts of other forms of discrimination that come out of a capitalist economic system—and also the climate crisis. These are serious problems that require us to think creatively, and we need to shy away from our fear of utopian thinking.

Robinson

Your answer made me think that there really is a double standard. I thought back to all the news headlines that have appeared over the last 15 or so years every time Elon Musk says that we’ll be colonizing Mars within two years, as if it’s a realistic thing.

Ghodsee

As if he doesn’t think that we’re going to be doing it as his indentured servants as well.

Robinson

Well, yes. What will the Mars colonies look like? I certainly don’t want whatever role I would have in one.

But there’s what is sometimes called the “techno-utopianism” of Silicon Valley, which often you posit as totally unrealistic—we’re going to merge with machines and upload our consciousness and do things we don’t know how to do.

But these other things you cover, which we do know how to do, are utopian, crazy, and unrealistic.

Ghodsee

Exactly. It’s like the Coalition for Radical Life Extension, these people out in Silicon Valley who are basically trying to be immortal.

If you’re talking about universal health care, that’s totally utopian, but immortality is totally feasible. It’s a really weird double standard that tech bros and billionaires and Saudi princes get to dream up cities in the desert or like this new plan for a utopian city in Solano County in Northern California, but the rest of us are just going to be stuck with a housing crisis and homelessness. Why can’t ordinary people dream in a way that imagines a better future, rather than just constantly ceding this territory of blue sky thinking to the tech bros and the billionaires and the Saudi princes who have the means, at least theoretically, to realize those dreams?

We have the means to realize dreams, too, if we work together. We may not have their resources, but we have something else, which is power in numbers.

Robinson

There are so many kinds of right-wing utopias, from seasteading to Ayn Rand‘s Galt’s Gulch, where all the businessmen go off to found their own community.

Ghodsee

It’s really important to realize that part of the reason we have this weird kind of allergy to utopian thinking is because from a very young age—at least if you were raised in the United States or the United Kingdom—you’re fed a constant diet of dystopian literature, whether it’s Lord of the Flies, 1984, Animal Farm, or Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World. In the United States, there’s a book called The Giver, which is perfectly attuned to tweens.

We get fed a steady diet of dystopianism in literature in schools. And then if you look at our popular culture, things like The Hunger Games, Squid Game, or Black Mirror, all sorts of shows that show us that the future will be this bleak, disgusting, awful place. So, we might as well just enjoy the present—it may not be great, but it’s better than what’s going to happen if we try to change it.

And so I do think we’ve been kind of drip fed from youth a fear of utopian thinking—and I’m not saying that there are some utopian ideas that we shouldn’t be fearful of. We have examples of people who claim to be building utopia, and they went terribly awry. I also want to be respectful of people who are afraid of charismatic leaders and cults of personality and things like that.

Robinson

Jonestown, etc.

Ghodsee

Exactly. We can’t ignore those things. But there are so many other examples that I deal with in the book of perfectly ordinary people who decide, for one reason or another, to change their lives in a positive way. And what I think distinguishes my book from the kind of techno-futurist utopianism that we often see in the public sphere about things like universal basic income, for instance, or universal inheritance, open borders, or the 15-hour workweek, is that in my studies of utopia, I’m really interested in the ways in which people are reorganizing their private lives. That’s what makes this a slightly different angle on this question.

Robinson

It certainly does, and I want to get to that. But first, I just remembered as you were talking about the dystopian children’s literature, there’s a wonderful review of your book by the great Liza Featherstone in Jacobin, and she begins with these reading the lists of dystopias that I had in school, too. She has this great quote:

“When I was a kid, I assumed that this was because the adults in charge hated children and wanted to give us major depressive disorder.”

She wrote, “We learn to recognize Newbery Award-winning books as the sign that the book would be a relentless bummer.” That is so true.

I wrote a long article about Elon Musk a while ago, and what struck me was, he has all his fans, and there’s even a children’s book about him called Elon Musk and the Quest for a Fantastic Future. But the whole idea is that he’s the only one among us who is dreaming of a fantastic future. I feel we can’t cede that territory to him.

Ghodsee

Absolutely not. It’s so important to realize that when we think about sort of ordinary things that we take for granted today, like no-fault divorce, or daycare centers—childcare where you drop your kids off and a bunch of other adults look after your kids while you’re at work—is those were initially utopian demands that were realized by a bunch of people working together and putting pressure on society and reorganizing their lives in such a way and made those things a reality. And so, to cede utopian dreaming of a better future to somebody like Elon Musk, or anyone, really, it’s not just him—it’s anyone who has the audacity to say, I’m the person who’s going to bring you this future—that’s a very dangerous thing. We need to decentralize and claim utopia for ourselves, understanding at the same time that utopia is always a horizon. It’s not a place that you actually ever really get to. It’s a place that you orient yourselves toward, and it’s in the orientation towards utopia that you make forward progress. This is why Oscar Wilde said, “a map that does not contain utopia is not even worth glancing at.”

Robinson

You cite, in your book, some of the Apple “think different” commercials that you’ve also mentioned, with all the pictures of the dreamers: Gandhi, Martin Luther King, John Lennon, and also Steve Jobs, so now you should buy our computer. You feel that tug when you see it because this is a natural human instinct to long for and dream of this better tomorrow.

Ghodsee

Yes, absolutely. When we think of visionary leaders of the past, people exactly like Gandhi or Martin Luther King, or even somebody like John Lennon, who spoke out against war and was often a thorn in the side of the establishment, I think we look up to those people because they were ideologically committed and brave. They took a stand. But if we actually look at them within the context within which they were living, they were persecuted, hated, and derided by members of their society. We exonerate them after the fact. I think that it’s important to realize that behind the kind of visionaries that Steve Jobs wanted to include himself among, there were movements. It wasn’t just individuals, they were movements. If you think about Gandhi’s Salt March, 60,000, people were jailed for harvesting salt against a British law that made it illegal to harvest salt. Eventually, the British just couldn’t keep putting everybody in jail. Gandhi led the initial march and had the idea to resist nonviolently, but it was the people who joined him on that march and who went out and openly defied the British law and collected salt that ultimately brought down the Raj. It was an incredible act of mass solidarity around this leader, and it didn’t happen just because Gandhi said so. It’s because there was something latent within that society that imagined a future without British imperialism. I think that we can imagine futures without many of the things that we are currently putting up with today,

Robinson

What you’ve just been saying reminded me that we had Robin D.G. Kelley on last year to talk about his book Freedom Dreams, which had just been reissued. One of the things that he says is that we consider social movements to be these very kind of gritty, grounded things that are pushing for very particular policies—the difficult work of organizing. But he said that what we often miss about social movements is that they all have this incredible, imaginative utopianism in them that is often the animating spirit behind movements. He’s trying to really show us that side of quotidian movement organizing.

Ghodsee

There’s a wonderful book about Black utopianism, for instance, and if you were a slave, imagining a world in which white and Black people were equal, that was completely utopian as a goal. That’s why the original series of Star Trek was so shocking when they just decided to have a racially integrated crew—in the future, this is just the way it’s going to be. There’s a way in which, within all social movements, within all attempts to create a better future, or to prevent a really awful future from coming in the case of the climate crisis, there is a core group of people—I sometimes like to call them the utopian 1%—who are just out there. They’re not just dreaming of a better future, they’re actually creating that future in the present, what anarchists sometimes call prefigurative politics: they’re living as if the future that they want to see is already here. And it’s in people that are making those decisions about how they’re organizing their lives, how they’re treating their colleagues, and how they’re being in the world that inspire other people to join them. I think that’s a really important force, and one that we should harness and not just cede to the tech bros, billionaires, and the Saudi princes who are out there trying to create alternative futures for us without our consent and without thinking about what is the best for humanity at large, rather than what is best for them as individuals.

Robinson

I knew that at some point Star Trek would come up because it comes up repeatedly in the book. Could you tell us why Star Trek has a place in this book on 2,000 years of utopian thinking?

Ghodsee

In many ways, this is a very capacious book. I start in Neolithic Çatalhöyük and go through the Pythagoreans—very few people know that Pythagoras was sort of the great-great-grandfather of utopian living in many ways—and I trace it through to the present day. One of the things that is really important is the role of popular culture—of art, literature, and cinema—and the ways in which we unbind our political imaginations from the present.

Star Trek has been a really important force in this endeavor for a relatively long time, and certainly in popular culture terms, for a pretty long time. It’s multigenerational and transnational. I think that one of the reasons that Star Trek is set apart from so many other sorts of popular imaginings of the future is its relentless positivity towards imagining a world in which a lot of the problems that we have today are just done with, gone, solved.

There’s a quote in the book from Whoopi Goldberg, who was a character in The Next Generation and who had been a Star Trek fan when she was quite young, about her seeing Nichelle Nichols, the actress who played Uhura. It gave her hope that there would be Black people in the future. These are her words—that’s what Uhura did for her. And I think Uhura played an important role for many people in all sorts of ways in which we, as I said, are just fed a constant diet of dystopianism about the present and the future. The best thing that we can do is imagine alternatives, and Star Trek is one of those alternatives that has touched many people around the world and across the generations.

Robinson

It is true that when you start to see something depicted in fiction, like the world of Star Trek, you can imagine how this sort of thing could work. And then you see these imaginary characters acting it out, and there’s a consistency to this world to the point where, at least in your mind, this alternative and totally imaginary world takes on a kind of reality. It implicitly poses the challenge to you, wouldn’t this be possible? Because if we’re showing how it would work, so why isn’t it possible? And then you think, maybe it is.

Ghodsee

Star Trek is a more than 50 year thought experiment in so many ways. If you think about the question of scarcity, in Star Trek there are these things called replicators, and basically, whatever you want, you just walk up to a machine, and you say, make me X, Y, or Z. In which case, material possessions don’t really matter anymore, and that’s a pretty radical idea if you think about it, especially living in the United States: the idea that your status as a human being would not in any way be reflected by your material possessions—not by your car, your clothes, where you live, or what kind of phone you carry around with.

So much of our personhood building, especially for young people, is around consumerism and how we express our identities through the consumer products that we use and associate ourselves with. So, if you take that away, and you basically imagine a world in which everybody can have everything that they want, whenever they want it, how are you going to differentiate yourself from other people? How are you going to be special? Star Trek says you might have hobbies and actually improve yourself—learn languages, play instruments, join acting clubs, read poetry. Whatever it is that you want to do, you’re no longer going to be concerned with how you present yourself through material things, but how you are as a person through the things that you do and the relationships that you have with others.

That’s a really interesting thought experiment, and Star Trek loves to do that kind of thing. It does get people to really think, if I had to express myself rather than being a “personal brand”, what would that look like? I think plenty of people don’t even know how to answer that question without the props of material culture that capitalism gives us.

Robinson

I want to return to what you mentioned earlier, which is that your book focuses on private life. You mentioned that obviously we have had in this country in the last few years, sort of since the Occupy movement, this resurgence of socialism that incorporates utopian thinking—you cite some other books like Fully Automated Luxury Communism. You write, “One of the most interesting aspects of this popular new utopianism lies in its primary focus on the public sphere. Today’s future positive writers critique our economies, while largely seeming to ignore anything that might be amiss in our private lives. But where we reside, how we raise and educate our children, our personal relationship to things, and the quality of our connections to friends, families, and partners, impact us as much as tax policies, the price of energy, or the way we organize formal employment.” So, through your book, you’re not just writing about utopian experiments, you have this particular focus on the sphere of the private. Could tell us more about that?

Ghodsee

So, when I wrote Why Women Have Better Sex Under Socialism in 2018, I was really thinking about policies that could be implemented in a kind of traditional socialist way from the state—state provided universal childcare and certain kinds of policies that would make it easier for families to raise children, healthcare being a big part of that. But, these were all sorts of policies that had to be directed to and then granted from a receptive state. After that book came out, I started to really think about, what happens when the state is not responsive, or when you don’t feel like you can actually democratically influence that state in any way, for all sorts of reasons? There are things that we can do in our private lives independent of the state that will start to get at some of these issues, that we have the full autonomy and ability to do right now, starting today.

So, that’s why I found these utopian experiments so interesting. Every single community that I looked at trans-historically and cross-culturally tended to coalesce around a similar pot mix of policies, about where we live, how we live, with whom we live, with whom we share our resources, and how we raise and educate our children. What I find really interesting is these kinds of more futuristic techno-utopias tend to really be policy oriented about things that we can do in the formal economic sphere to make life more amenable to human flourishing, what Noam Chomsky sometimes calls “expanding the floor of the cage.” And for me, I want to think about, what is it about the family and our relations with each other in our domestic private lives that is also playing a role in upholding this system? Are there ways, if we start to change our domestic and private relations with each other, that will ultimately, down the road, impact the system itself?

So again, this is a sort of bottom-up change that I’m talking about. I actually think there’s very good evidence to show that if we started living differently—if we gave up the idea of the nuclear family and that romantic relationships are the appropriate container for parenthood, of the single family home in the suburbs with our private car in which we commute to and from work—all of those things are pieces of an economic system that is exacerbating inequality, isolation, and loneliness, as well as the climate crisis. And so, we can do things very specifically to reverse some of these trends by making changes in our private lives.

Robinson

Tell us a little bit more about the kinds of communities that you are profiling in this book, and the ways in which living in them differs from living outside of them.

Ghodsee

Yes, there’s a real range in this book. The extremes are places like the traditional kibbutzim in Israel, intentional communities like Twin Oaks in rural Virginia, or eco villages like Tamera in southern Portugal, where you really have a group of people who are living together in a very communal way, sharing property and raising children in common, and they have a very sort of different view. And there are also religious analogues to this. There are people like the Bruderhof or the Hutterites; there are groups that take very seriously Acts 2 and 4 of the Bible, these verses where it says very clearly that the early followers of Christ—the disciples—shared all their property in common and lived together communally.

And then there are models like co-housing or even co-living, which is a better mix, perhaps, of privacy and community where you might have your own private dwelling, but you’re submerged within a greater community where there are structured interactions with your neighbors and colleagues, and sometimes labor requirements and more shared resources. And then there are just things like people who get a house together that are not related to each other, but they live together, like “mommunes”: a bunch of single moms who will buy a house and raise their kids together. So, this really runs the gamut. The key thing is that often these are what I call in the book nonconsanguineous, but the better way of saying that is not blood related. So, a group of people who are not necessarily related by blood or by filial family ties—”mommunes” would be the best example. For unrelated women—they’re not sisters, they’re not cousins—who happen to have children without partners, and they decide together to buy a house and raise those children together in that house.

That is a model that goes back to antiquity, if not way before that. We know that we are cooperative breeders. We have often had other adults that are not blood related to our children in our lives. This may sound really radical, but in fact, some of the most traditional religious communities have godparents, and godparents are often friends of the parents that are meant to play a really important role in the raising of children. So, the pieces of this, this sort of target of my book, is the idea that we have a nuclear family where the romantic relationship, usually, but not always, heterosexual, is the appropriate container for parenthood and that the biological parents provide exclusive bi-parental care for their biological offspring in a single family home surrounded by hordes of their privately owned stuff. That’s the model that we think of today as the ideal family—you made it, you’re not a loser if you manage to do that.

But it turns out that there are all sorts of people that would agree that, to quote David Brooks, “the nuclear family was a mistake.” There is a way in which this model of child-rearing is really problematic because romantic relationships are fragile, and it turns out that child-rearing actually makes them even more fragile. And so, if that primary romantic relationship breaks up, then the children are kind of the collateral damage of the breaking of that relationship. If we submerge these relationships into wider lateral networks of care and emotional support from other loving adults—these could be grandparents, aunts and uncles, colleagues, neighbors, friends, people from your religious community, these could be anybody—the idea is having other loving, caring adults in the lives of children. It makes it easier for us to raise children, it’s psychologically more healthy for those children, and it also takes pressure off our romantic relationships because we have other adults upon which we can rely on when the pressures of parenting become too difficult for us to bear.

Robinson

When Sophie Lewis was on the program a few months ago and discussing this, one of the things that came up in that conversation is that nuclear families guarantee inequality because they guarantee that how you do in life is going to depend on your luck in the parent lottery. If you get bad luck in the parent lottery, that sucks for you. But if you have those broader networks, as you say, there’s a cushion there. And even if you don’t get the luck in the parent lottery—you don’t have the fortune to have parents who are loving and devoted—there are other people in your lives who are.

Ghodsee

Right. It’s not only that. I also think that the nuclear family as it is currently instantiated in most Western countries is a primary node, if not the primary node, in a capitalist society that allows for the intergenerational transfer of wealth and privilege, usually from fathers to their legitimate sons. Now, this predates capitalism. This is how it worked in feudalism, and is actually how it worked in antiquity during slavery. The thing is that we often in our college years, or in our 20s, we tend to live with a wider network of people. When we get older, many people move into 55 plus communities or senior living facilities, where they live also with a greater number of other non-blood-related adults. But it’s only at this moment when we’re raising children, where we feel compelled to retreat into the single family home in the suburbs or wherever, that we provide this exclusive bi-parental care to our offspring.

Why do we do that? It’s because parenting is like a contact sport. I’m a mom, and I know that it’s really difficult. When you have a kid, you feel like you have an obligation to give them the best life that you can give them. This is exactly this idea that if you win the parent lottery, you do well. But it’s also that the nuclear family creates a situation in which other nuclear families are not your friends, they’re your competitors. You’re all competing for scarce resources—educational attention, spots in universities, first violin in whatever orchestra your kid is playing.

There are all sorts of ways in which the institution of the nuclear family creates competition between parents and children, when if we had a more capacious idea of family and a more cooperative view of child-rearing, we would have much greater levels of equality in our society. The family would no longer play this primary role in facilitating the intergenerational transfer of wealth and privilege.

Robinson

It seems to me that a really important aspect of the kinds of communities that you’re describing here, a big part of the purpose of trying to form them, is to make people’s lives easier. It’s more difficult to make friends and raise your children when we live in an isolating society. When we help each other, everything becomes easier. Life becomes a lot less stressful and lonely.

Ghodsee

It’s not rocket science here. This is why I think it’s kind of funny to even use the term utopian, when what I’m talking about is probably how human beings lived for millennia. The idea is we would be happier, more connected, our children would thrive, our societies would be healthier, and have more community ties. There was a great article in The Atlantic by Hillary Rodham Clinton called “The Weaponization of Loneliness,” about how loneliness is what fuels these conspiracy rabbit holes that people are going down, and they sort of end up in an alternate reality because they’re so isolated from actual human beings, and their primary social relationships are with talking heads on the internet and conspiracy theorists and things like that. And so, there’s a way in which study after study shows that our weak ties, our community engagement, are fundamental to our health and well-being. They’re saying now that loneliness and isolation is like smoking 15 cigarettes a day in the negative health effects that it has on our bodies. The Surgeon General is really concerned about isolation and loneliness in the United States and what’s going to happen to our public health. It’s a public health crisis. Not to mention the deaths of despair, the suicide, the opioid abuse, the alcoholism. There’s so many negative downstream consequences of our isolation and loneliness, and it’s such an easy problem to fix.

The thing is that we’ve inherited a built environment from the 20th century, from the Cold War, and that is a big part of the problem. That’s why the tech bros in Northern California want to build a new city for themselves to live in, one that has all the amenities of being able to walk and community interaction on a daily basis, while the rest of us inhabit this crumbling facade of American prosperity of the 1950s and 1960s or whatever. I do think that this is a key issue. I think the term that I use in the book is family expansionism; we have to radically expand our definition of family, and this can mean chosen family, but this could be an extended family. This could also just mean creating lateral bonds to people.

The Russian theorist Alexandra Kollontai called this “comradely love,” and she believed that if we lived in a society with many more lateral ties with people who supported us emotionally and were basically there for us when we needed them, and we were there for them, so many of the problems that we face in the present day could be eradicated just by increasing our social relationships with others.

Robinson

Just to conclude here, I want to dwell briefly on the common criticism of utopian thinking. The Wall Street Journal reviewed your book, which I was surprised by, and they’re horrified.

Ghodsee

Horrified! Yes.

Robinson

The revival of all this terrible utopian thinking that ruined the 20th century and led to authoritarianism and tyranny. And they wrote, “This book is a reminder of why intellectuals should never be placed in positions of authority.” I feel like that formula has it exactly backwards. You were talking earlier about the way in which the kind of techno-utopian capitalist stuff is imposed on us without our consent. What you’re talking about is finding ways to organize our communities democratically by choice—by free human choice—in ways that that suit us, in ways that enable our flourishing. Could respond to this common fear that any attempt to reorganize social life inevitably turns into the Khmer Rouge?

Ghodsee

First of all, I do think there’s an assumption that it’s going to be a top-down reorganization, and that’s where I did feel that the Wall Street Journal review was quite disingenuous. They were talking about top-down when my entire book was about bottom-up. It made me wonder if they actually read the book, or if they just sort of went off the blurb on the description and my previous writing or something like that, because it’s a very different book in the sense that I’m talking about things that we can do democratically to change the conditions of our daily lives in order to be more connected and contented with each other.

But I do think that this sort of fearmongering is precisely a tactic to get us to accept the status quo. There’s a conference in Texas somewhere called Natal—a pronatalist conference—and on their website, it says that because the population is declining in most advanced capitalist countries, economic systems that rely on continuous growth are at risk.

So, there’s a real fear right now because people are making independent decisions not to have children, and the declining birth rate around the world, for people in power, is really starting to worry them. That’s why we’re seeing a lot of rollbacks of previous rights that we had in terms of reproductive freedoms. There’s a real fear that if people stop having children, we could be facing a degrowth future. Certainly, from a climate perspective, that’s not necessarily a bad thing. But the one thing that is really interesting about this is it assumes that there’s only one way to have children, and that’s the nuclear family in your single family home in the suburbs with your stuff and car.

What I want to argue is that there are other ways. I hear talk about tri-parenting and multi-parenting. Why? We know economically that children who have two parents do better than children who have one, but why not have three, four, or more? Why doesn’t that logic hold if we just expand that notion of the family? And so, I do think that fearmongering around any changes that we make to our private lives, especially around the family, is ultimately fearmongering around the stability of our economic and political system.

So, even though they will claim that this is utopian, unrealistic, and these kinds of experiments always fail and are a slippery slide to the Gulag, at root, they’re really afraid of them. Because if people wake up one day and just say, I think I’m going to live my life differently—this idea of prefigurative politics. I’m going to live my life in a way that doesn’t participate in this sort of crazy consumer treadmill—the hedonic treadmill that social psychologists talk about. I’m going to live my life in a way that shares resources rather than hoards them. I’m going to raise my children with a bunch of other people. I’m going to be happy, and I am not going to allow the attention brokers to steal my eyeballs away from the people in my life that are making me happy. I think that that is a real threat to the system.

And in this way, this sort of personal changing of your life is really profoundly political. Every time you hang out with a friend in the park, or you drink a bottle of wine or have a couple of beers down at the pub, and you’re happy and you’re connecting with somebody, you are doing something really important. It doesn’t feel like it, but it’s very important and ultimately very political.

Hear the full conversation on the Current Affairs podcast. Transcript edited by Patrick Farnsworth.