Voters Have the Right to Be Dissatisfied with ‘Bidenomics’

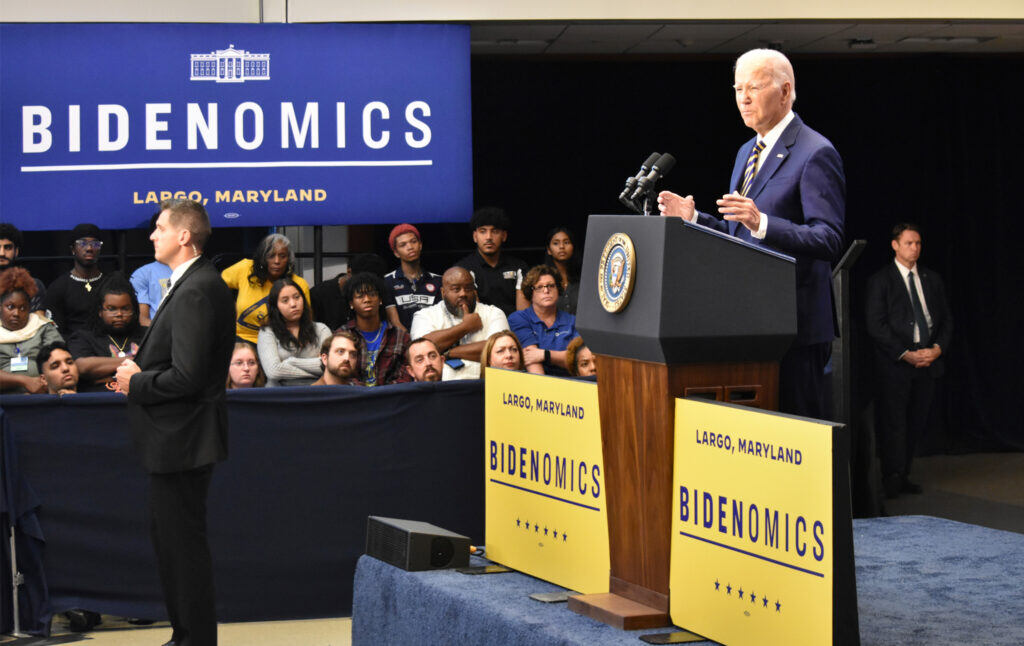

The president’s defenders think voters are ungrateful for a good economy. But people’s economic experiences vary widely, and much of the country has little to appreciate Biden for.

As the 2024 election approaches, President Biden’s prospects for re-election are in serious doubt. As of September 2023, most polls have him virtually tied with Donald Trump in terms of the national popular vote—an outcome which, even if he improved his margin by a few percentage points, would result in an Electoral College loss for the president. Even two-thirds of Democratic voters do not want him to run for re-election.

Looking at issue polling, the biggest millstone around Biden’s neck has been the performance of the economy. According to a recent poll from the Suffolk University Sawyer Business School and USA Today,

Nearly 70% of Americans said the economy is getting worse, according to the poll, while only 22% said the economy is improving. Eighty-four percent of Americans said their cost of living is rising, and nearly half of Americans, 49%, blamed food and grocery prices as the main driver.

This is in spite of messaging from the administration, which has aggressively coined the term “Bidenomics.” The President published an op-ed in the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel touting the ways in which “Bidenomics is working.” Biden wrote:

More than 13 million jobs, including 800,000 in manufacturing. Unemployment below 4 percent for the longest stretch in 50 years. More working-age Americans are employed than at any time in the past 20 years. Inflation is near its lowest point in over two years. Wages and job satisfaction are up. Restoring the pensions of millions of retired union workers – the biggest step of its kind in the past fifty years.

But just looking at those top-line macroeconomic indicators does not tell the full story of what Americans are actually experiencing in their daily lives, which could give insight into their dissatisfaction.

For one thing, just because wages are catching up with inflation doesn’t mean we can erase the nearly two years during which they trailed behind. And though low-income workers have seen the greatest wage gains in recent years, polling from Morning Consult suggests that many families are still acutely feeling the effects of inflation. Forty-six percent of Americans say they don’t believe they could afford a surprise $400 expense—a number that has remained virtually stagnant since the beginning of the year despite the supposedly improving economy. Among Americans making less than $50,000 annually, only a third say they could afford such an expense.

While fixating on the top-line numbers, Biden ignores the many ways in which Americans are worse off after pandemic-era social spending programs and economic interventions expired. Since the expiration of the federal eviction moratorium in 2021, the rate of eviction filings per month had doubled by January 2023, according to Princeton’s Eviction Lab. And in August 2023 alone, more than 86,000 eviction filings were made by landlords nationwide. Housing costs, which were already climbing rapidly prior to Biden taking office, have exploded post-pandemic. The average home, which cost just over $270,000 in January 2021 costs just under $350,000 in September 2023, according to Zillow. Habitat for Humanity estimates that more than 2.4 million people were priced out of the housing market in 2022. And though rent increases have slowed to pre-pandemic levels, the average asking rent has jumped from $1,639 in January 2021 to $2,052 in August 2023—a 25 percent increase—according to research from Rent.com. A recent Habitat for Humanity report found that nearly half of all renters—an all-time high—were “cost-burdened,” meaning that they spent 30 percent or more of their income on rent, while a quarter of renters spent more than half their income on rent.

Student loan payments are starting up again, which means 44 million borrowers will have to once again make payments, which cost more than $500 per month on average. Many are also still reeling after being promised debt forgiveness only to see it overturned by the Supreme Court.

As a result of a spending bill mostly passed by Democrats and signed by Biden, nearly 5.5 million people had been kicked off Medicaid as of late August—mostly for failing to fill out the proper paperwork—as Congress and the Biden administration once again allowed states to begin purging rolls after they were temporarily barred from doing so amid the pandemic. The Department of Health and Human Services estimates that 15 million people could be kicked off the program by next summer. As of 2022, 27.6 million Americans already lacked health insurance.

Perhaps the most gutting statistic we’ve seen over the past year has been the resurgence of child poverty across the United States. As part of the American Rescue Plan, the pandemic stimulus package passed by the Biden administration in 2021 increased the Child Tax Credit—which goes to married couples with incomes under $150,000 annually, single-parent families making under $112,500, and everyone else making under $75,000. Instead of $2,000, families received $3,600 for each child under six and $3,000 for each child between 7 and 17.

The program was a roaring success. According to the Census Bureau, nearly 3 million children were lifted out of poverty during 2021 as a direct result of the expanded CTC, and the percentage of children in poverty was cut nearly in half, from 9.7 percent to 5.2 percent—the lowest percentage on record.

But Congress did not continue the Child Tax Credit expansion—they allowed it to expire at the end of 2021—and Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema, a pair of Democrat deficit hawks who have killed many of the social spending measures proposed by Democrats when they held a governing trifecta, voted with Republicans to kill it, with Manchin making baseless claims that some parents would use the money to buy drugs.

Recent numbers show that canceling the Child Tax Credit expansion has been catastrophic. A new Census Bureau report shows that not only did the child poverty rate increase in the U.S. for the first time in thirteen years, but it more than doubled between 2021 and 2022—jumping from just 5.2 percent to 12.4 percent.

A lot of Biden’s biggest defenders in the media speak about the public as if they are too dumb to understand their own economic situations. The New York Times’ house economist Paul Krugman blamed “partisanship,” “media reports,” and “recession pessimism” from economists for negative feelings about the economy. Brookings Institute economist Justin Wolfers went on MSNBC to dismiss Americans’ economic fears, saying they “tell themselves stories that are completely at odds with reality.” Will Stancil, a researcher at the University of Minnesota’s Institute on Metropolitan Opportunity and a former Atlantic columnist, has argued on Twitter that “The best explanation [of] Biden’s low economic approval is media vibes. People do not accurately perceive real-world economic indicators around them and predictably adjust their politics. Instead, they internalize narrative descriptions of the world, mostly from media.”

The idea that media narratives are creating false perceptions about the economy is not entirely incorrect. There is certainly a tendency to blame Biden for every economic ill we face without taking any wider context into account. For example, Republicans who blamed Biden for record inflation in 2022 usually ignored that inflation in Europe was even worse during the same period. They also blamed him for rising gas prices, even though the price of oil had increased worldwide.

Biden also does not bear full responsibility for pieces of his agenda that have fallen flat in Congress due to the obstinacy of his fellow Democrats. The death of the expanded Child Tax Credit in the Senate, for example, can’t really be laid at his feet—though it’s fair to wonder if he and other Democrats could have put more pressure on Manchin and Sinema not to kill what has been arguably his most successful economic program. Meanwhile, he has tried to cancel some student debt and stem the tide of evictions and by passing a new eviction moratorium but was stymied by a right-wing Supreme Court (he has balked at actually doing something about that Court).

But just because every economic failure is not solely Biden’s fault doesn’t mean that people’s experiences of economic struggle are any less real. Even if they don’t blame him for their circumstances, can you really expect someone to thank Biden for the state of the economy when they’re struggling to pay for rent, healthcare, and food, drowning in student debt, or live in fear of a surprise $400 payment?

This is especially the case when there are measures Biden could have taken or still can take to ease people’s economic burdens but hasn’t. For example, instead of attempting the piecemeal strategy of wiping out only $10,000 of student debt for borrowers who make less than $125,000 individually using the legally unsound HEROES Act—a move which was killed by the Supreme Court earlier this year—he could have swung for the fences and canceled all of it using his powers under the Higher Education Act and dared the Supreme Court to screw over nearly 44 million borrowers.

Biden has bullets in the chamber to combat inflation as well. He has acknowledged that record corporate profits are a major driver of high prices—a reality that even the famously pro-market and pro-austerity International Monetary Fund admits. But while he has taken positive steps to reduce the price of prescription drugs, there is far more he could do to address the prices of energy and food.

Putting more investment into renewable energy and speeding up the creation of wind and solar infrastructure—while also being critical to prevent the ravages of climate change—would also have the effect of forcing oil companies to compete with green energy, which is fast becoming cheaper to produce than fossil fuels. According to a 2021 report from the International Renewable Energy Agency, 62 percent of total renewable power generation projects added last year cost less than the cheapest new fossil fuel option. And green energy production is expected to become even cheaper as infrastructure expands and technology improves—currently the costs of wind and solar power are dropping by 10 percent each year. Homes that run on renewable energy save on energy bills. According to a report from Forbes, people with solar panel systems strong enough to cover their energy needs save around $1,500 per year on average while electric vehicles have been found to save consumers more than $4,700 on fuel over the first seven years of ownership. Several studies have indicated that abundant green energy—which is domestically produced—can and does reduce the power of volatile global oil markets and combats inflation.

To cut gas prices in the short term (and reduce fossil fuel use globally), Biden could declare a climate emergency. Using powers delegated by Congress under the National Emergencies Act, he could then unilaterally reinstate America’s ban on crude oil exports, which was in place for 40 years before Congress ended it in 2015. A climate emergency declaration would also allow him to hasten the green transition, allowing renewables to serve as a formidable competitor to the oil cartels that have driven up prices. According to a memo from the Center for Biological Diversity, Biden could use the Defense Production Act to marshal up to $650 billion per year “to manufacture renewable energy and clean transportation technologies.” All that new construction would more than offset the number of jobs lost in the fossil fuel industry. According to the World Resources Institute, “Additional federal policies that bring U.S. emissions down to net-zero by 2050 can create an extra 2.3 million net jobs by 2035,” in addition to the 900,000 expected to be created by 2035 as a result of energy investment in the Inflation Reduction Act.

Lowering food costs would partially be accomplished by a reduction in the cost of fuel (as gas prices increase, so do the costs of producing and transporting food and other consumer goods). But Biden has executive powers that could fight food inflation as well. His Department of Agriculture could stabilize prices using price “smoothening” methods utilized by previous presidents in times of high inflation. Representative Ro Khanna (D-CA-17) recommended this last year—when inflation was at a 40-year high, writing in a New York Times op-ed:

We can do this through pre-emptive buying, a tool we’ve used since World War II. The Department of Agriculture should purchase essential food products on the global market during significant price dips, which often occur multiple times a month or even every week, and resell them cheaply to Americans. The department should contract with private wholesalers for distribution, as it has done for decades to avoid storage or logistical challenges. Because the government would be buying and selling large quantities of food when they are cheapest, this would lower and stabilize prices for key grocery store products within weeks… Our executive branch has the authority to do this: Presidents from Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan to Barack Obama and Donald Trump have instructed the Department of Agriculture to spend billions on dairy purchases to influence prices.

This is to say nothing of the long-term structural changes Biden could have fought harder to achieve, but either outright opposed or let fall by the wayside. For instance, he could have made any kind of effort to pass the public health insurance option he vociferously campaigned on. The Urban Institute estimated such a program could reduce premiums by 12 to 28 percent. (We’d of course prefer a single-payer system, but this is Biden we’re talking about.) Instead, he totally abandoned it as a priority once he came into office, despite working with a Democratic House and Senate during his first two years.

Meanwhile, the minimum wage in the U.S. is at a 66-year low in terms of real value and is not even half enough for a full-time employee to afford a one-bedroom apartment anywhere in the United States. On the campaign trail, Biden promised to raise it to $15 an hour, but it was thwarted on procedural grounds by the Senate parliamentarian—an unelected advisor whose authority can be overruled. His vice president Kamala Harris (the president of the Senate) could have fired or overruled the parliamentarian to press ahead with increasing the minimum wage. Instead, the White House issued a statement saying Biden was “disappointed” and then moved on from the issue, never seriously pursuing it again.

Democratic voters have the right to be frustrated with Biden when he doesn’t follow through on his promises, especially when those promises were often already compromises in the first place and even more so when the economy is still trampling over millions of people.

You can point to metrics like slowing inflation and low unemployment all day, but just because they are general trends doesn’t mean everybody is feeling them equally. Even if you can quantify the ways in which things are getting better (just as I have quantified the ways they are getting worse), people process the conditions of their own lives on a more visceral level than they will process lines on a graph. Things may be getting better or worse on aggregate, but people do not live in the aggregate. If people in dire economic straits recognize their situation as an outcome of politics (as they should), of course they are going to feel distaste for the people in power, no matter what has been happening elsewhere. Would you say that it’s irrational for a homeless person to be mad at politicians for housing costs even if rents happen to be coming down?

But even if you are not personally struggling, there’s a good chance you know someone, or many people, who are. Paul Krugman often makes the point that people who respond to polls “are feeling good about their personal situation but believe that bad things are happening to other people” and attributes that dissonance to partisanship and pessimistic media coverage. But, again, nearly half of Americans say they wouldn’t be able to afford a surprise $400 payment. Unless you live in a totally disconnected bubble of privilege, there’s a good chance you know at least a few of them.

The reality of life in America is the ambient sense of poverty in the midst of plenty. It’s seeing homeless encampments next to Beverly Hills. It’s GoFundMe pages that help people buy insulin from a company whose CEO received a salary of $21 million last year. Whatever the economic trends, these sorts of sights are constants no matter who is president. And whether you are personally struggling or know people who are, that will always be more palpable than lines on a graph.