How the Idea of Being “Self-Made” Arose

How did we come to believe that we can be anything we want to be? And what are the consequences of ascribing godlike powers of self-creation to human beings? Author Tara Isabella Burton explains the culture of “self-making.”

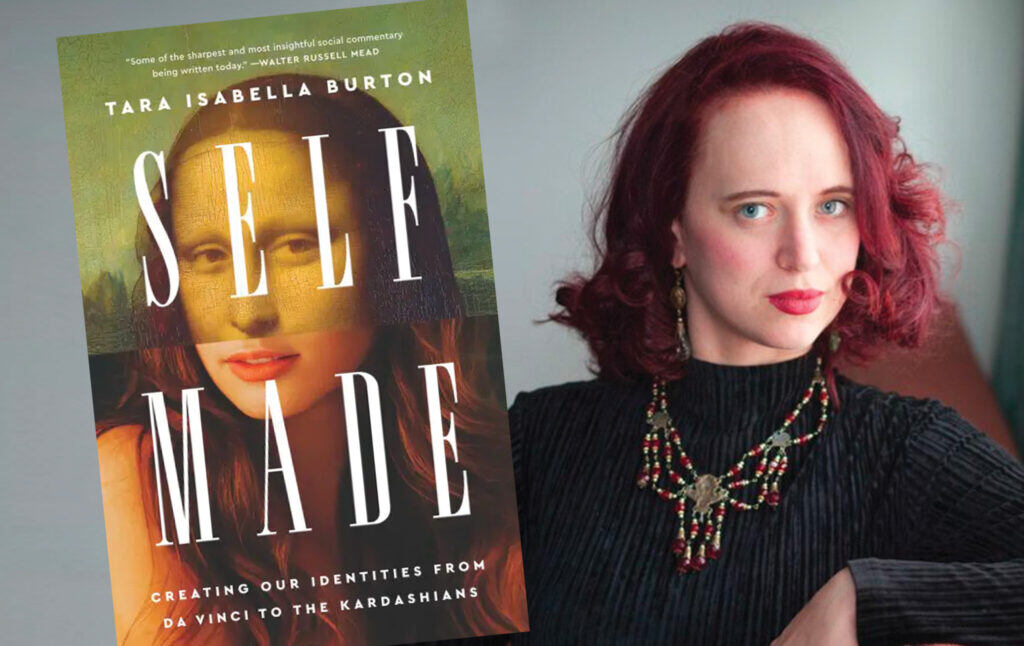

Tara Isabella Burton is a novelist and the author of the new nonfiction book Self-Made: Creating Our Identities from Da Vinci to the Kardashians, a history of the rise of the idea of a curated self. Tara’s book looks at the transition from seeing human beings as made by God to being made by our own individual wills. From Renaissance painters to the famous dandy Beau Brummell to Thomas Edison to contemporary Instagram influencers and reality television stars, Tara looks at those who have carefully manufactured the picture of themselves that they show to the rest of the world. Today she joins to discuss whether, in becoming free to “self-make,” we have in fact truly been liberated, and what unseen forces shape people’s ideas of the selves they ought to become.

Nathan J. Robinson

Your new book profiles many eclectic figures, from the guy who painted himself to look like Jesus during the Renaissance, to the Andy Warhol superstars, the Kardashians, the guy who made the Whole Earth Catalog, Oscar Wilde and dandies, and Thomas Edison. What is it that unites all the figures that you profile from chapter to chapter under this single, unifying framework?

Tara Isabella Burton

It’s not just that they’re successful self-makers—which is to say either that they are people who come from situations of either economic deprivation or mediocrity and become wealthy—nor is it exclusively that they live their lives as a work of art, although many do. What unites these two disparate groups is their conviction that, basically, we are able to shape our own selves in a sort of deep way, that who we are is what we want to be, and the inner work and the work of managing perception of others all works together to fulfill the most human of purposes, which is, to quote the Renaissance humanist Pico della Mirandola, “fashion ourselves.”

What being human means is deciding who we are, and this ideology, explicit and implicit in various works or lives of these figures, are all very much participating in that vision.

Robinson

You said that what unites them is this conviction that we decide who we are—we can make who we are. I feel as if this idea has wormed itself so deeply into our thinking today that I can imagine people hearing you say this and thinking “What’s so strange about that?? In a way, what you’re doing with this book is you’re taking what seems obvious and trying to make it seem unfamiliar to us again. I want to ask you, what is the alternative? What preceded this view? If not the view that “we make ourselves,” is it the view that the “world makes us”? What is this view that you’re describing a departure from?

Burton

I’m a theologian, so I see everything as a theological problem. I think the departure we’re looking at is the idea that we are made by God. In particular, this is a book about the West primarily, and about the transition between the Medieval and Renaissance Europe. So, it is a book specifically about Orthodox Christian Catholic theology and it’s recession from the public sphere. Obviously, any generalization is reductionist, but roughly speaking, I think we can talk about a pre-modern, pre-Renaissance vision of the self, that we are created in the image or likeness of God, but we are created by God.

What that means is that we are part of creation—everything that is, is part of a unified, meaningful whole. Whether it’s the knowledge and love of God or expressing the glory of God, our purpose is not for ourselves, but for some greater end. This is what links a human being to a plant, an animal, a river. We tend towards something, and that something is outside ourselves and ultimately, our emotional state or our inner lives is something that, if it is to be cultivated, it is to be cultivated and conformed in pursuit of virtue or in pursuit of saintliness so that we might better fit ourselves to the purpose outside us.

And roughly speaking, what started somewhat in the Renaissance and really gathered steam in the European Enlightenment is this idea that our purpose is outside us, and also that our role in the social order is part of creation. This is, I think, a really big distinction that we see around Enlightenment thought, which is the idea that our social roles—as neighbor, as princess, as king, as peasant, what have you—are somehow part of who we really are. It is part of creation and part of what we are meant to be. It may not be the totality of it, but it says something about us.

And then, the sort of big dirty word in the Enlightenment becomes this idea of custom, that our social lives—our social imaginaries—are not fixed or God given. They’re just kind of random, and this is something that gets explored in various ways. One of the most popular genres of exploring this is the traveler’s tale. So, either visitors from the so-called New World, or from the Far East, who come to Europe, or vice versa, are theorized by French writers—I’m thinking of Diderot and Montesquieu, Persian Letters and others—but the whole genre that’s people looking at the way things are done in Europe or elsewhere and thinking, gosh, this is so weird; there’s a funny man in a magic hat who says he can turn wine into blood—that’s so crazy. What’s being done constantly throughout this genre of writing is trying to conceive of social life and relational social life as just arbitrary and subject to change. It’s just custom. Therefore, it doesn’t have any real weight.

And the question that comes out of this, then, is: what does have weight? What matters? Or, to put it really simply: what makes us “us”? And increasingly, the bit of us that makes us “us”, rather than the bit of us that the world puts on or ascribes or demands of us, is our internal states, our psychological reality, and ultimately, I argue, our desires. What we want is seen as more constitutive of who we really are than our social plays, our familial role, or things that are in the post-Enlightenment mind, broadly speaking, thrust upon us by society, rather than being organic and innate to our selfhood.

Robinson

So, I guess it wouldn’t occur to us to look at plants and other animals and think that they could be “self-made,” that they could will themselves into being whatever they want to be. And until the point that you’re describing, human beings accepted that we were one piece of existence and had pretty limited control over who we are. Because as you say, we are not creators—there is a “Creator,” we are created, and we are the stuff that was made, not the stuff that does the making.

But once you start to think of yourself as capable of doing the making yourself, it’s immensely liberating. Throughout the book, you treat this as not wholly good or bad—it’s very mixed. Because on the one hand, if you start to think of yourself as having the godlike power to determine who you are, and tradition is just custom, then you can actually have faith in fixing injustices. You will think that we can have the kind of society that we want—about who we are and what we want. But on the other hand, as you point out, it can sort of lead towards the idea of the fascist superman.

Burton

Absolutely. It absolutely leads there, or more broadly, I think it leads towards a vision that the most “human” human is the human who self-creates. I think that this is an implicit cultural assumption now that is rarely stated explicitly like this, but is the underpinning of every kind of “be your best self”, “self actualization”, “self-care”, “doing the work” language that’s just like the miasma that we breathe, culturally speaking. It’s that the thing that makes us human is our “humaning”: to be human to a greater and lesser extent.

There’s an act of self-creation, this kind of willful decision to be who we want to be and manifest that, that is the benchmark of how good we are at this whole human thing. And so, people who cannot or will not, for whatever reason—and I think different historical eras have different conceptions of exactly what those other non-self maker people are doing—but those who do not appear to be self-making in the mold of either a Grimes or an Elon Musk—either the entrepreneur or the pop star celebrity—are somehow failing or lesser. It’s because they don’t innately have “it”. The mysterious quality that self-makers have is so hard to define that half of the language we have for it is messy, like “je ne sais quoi”, which is English people using French because maybe if it’s in French…

Robinson

—it’s true. It’s insightful and true!

Burton

Yes. We can get past the fact that no one knows what it means. Or, of course, in old Hollywood, “it” in quotations—that mysterious quality. “It” might be innate; therefore, some people are just worse because they don’t have it. Or, it’s willed or a matter of hard work and some people are not focusing enough.

I argue and believe that ultimately, by the 20th century, the kind of innateness model and the hard work model converged somewhere around the time of old Hollywood, I would say, and we get basically a theology of desire. The thing that means that you are a self-maker is that you want it badly enough, and that desire is constitutive of being a special kind of hungry person.

Robinson

I’m supposed to go later this afternoon onto—I don’t know why I agreed to this, but I agree to pretty much anything—a right-wing talk show in Britain. I think we’re debating manfluencers, and they believe very strongly that there is this alpha/beta male category. I was reading the writings of the person I’m supposed to debate—and they think there’s the alpha male, the guy who is the self-making guy, and the more you are in control, the more of a man that you are, whereas the weak passive man allows themselves to be influenced rather than doing the influencing. It’s this idea that you are more of what you ought to be to the degree that you can control others, rather than just floating through life like a leaf in the wind.

Burton

I find manfluencers fascinating. I’ll try and be extra charitable here, but what interests me about them is that there’s precisely this tension between this vision of a pre-modern existence that’s about dominance hierarchies, and—I’m paraphrasing here—now that democracy and equality have eroded these natural distinctions between people, everything is confused, and we would like to return to a time when there was meaningfulness.

I feel like there’s a version of this that is the “through a glass darkly” version of an argument that I make in terms of seeing a difference between the modern and pre-modern vision of the self, although I want to be clear that I do not think it is the unmitigated tragedy that they do. That said, I think that what’s really interesting is there’s some sort of hunger for some kind of reality, some kind of basis of something, and yet the way that it is conceived of and gets sold as is this fundamentally modern vision of this self-controlling self who also controls others—the person who is a member of the lobster trad dominance evolutionary hierarchy, but is also the Nietzschean Superman at the same time—the person who stands outside the world and shapes it.

I suppose I have a degree of sympathy for a desire to recover a sense of reality in a world where things often do feel unreal or alienating for a variety of reasons. And yet, what fascinates me is precisely that you could do nothing less trad in a sense than trying to make yourself via self-help techniques. That’s not to say there’s not a place for personal discipline, virtue ethics, or other kinds of schools of thought that are about the control of the self for a greater end. But a very important distinction between, say, reading the lives of the saints as a medieval person and this is, what is that purpose? What is this all for at the end of the day? Does this fit into a wider moral vision? Or is this just about self-actualization, personal contentment, and worldly success?

I think that difference is actually quite a big one. Ultimately, if it’s only for yourself and not for anything, if you don’t have a sense of the architecture of the universe and tending towards a collective wider moral purpose, what is left but the dominance hierarchies and the ability to wield power? And I think that what ends up happening with a lot of these figures, including taking to the extreme visions of Wildean dandyism—which I have historically been a big fan of—is ultimately, there is a certain nihilism in it, which comes from the sense that nothing means anything but what you make it.

And so, the shaping of perception, in one’s public image more broadly, takes on something different. In this moral framework, it’s not lying. I think it’s lying, but if reality is completely fungible and kind of meaningless, reality is only what you make it. The real world is the network of perceptions, the lattice of social imaginary, which means creating yourself in a certain way is actually just shaping reality in your image. You are making truth because you are responsible for making reality. You find this in figures like Mussolini, when he talks about shaping the crowd—he’s the artist, they’re the clay, and he’s moving them with his fingers in a particular way.

You find this in the way that Donald Trump talks about the art of the deal, which was very influenced by Norman Vincent Peale and other practitioners of New Thought, this quintessentially American self-help tradition that’s all basically proto-manifesting: reality is what you make it; if you convince people of stuff, it becomes true. And in an era where more and more of us live online—almost 80% of Americans have smartphones—much of our shared reality is social reality, in that it’s not physically embodied. Suddenly, massaging that reality is a lot easier. It is a lot easier to do the meme magic than it was before the internet.

And so, increasingly, Self-Made and the work that I’m doing after Self-Made, started out just as a history of self-creation, but I think it’s also about reality creation, or about how we think of what is real, how we think of manipulating that reality, and its reference to the capital “R” Real out there.

Robinson

Right. We have kind of no choice but to think about who we want to be and what we’re going to make of ourselves to a certain extent. But you have this really nice passage that I just want to read at the end because I think it captures your ultimate mixed verdict on this change. You’re not arguing the story of self-creation is straightforwardly tragic, and in fact,

“…the promise offers the potential for genuine liberation. The early Americans called self cultivation, and the ideal that if we learn to govern ourselves emotionally, we can better govern ourselves politically, is and should remain an inspiring one. our ability to create, to imagine, to dream better lives for ourselves, and those around us, and our freedom to transform those dreams into social realities, are among the most vital and human parts of ourselves. But this seemingly liberatory promise that we could create ourselves has, as often as not, been warped into an excuse to create implicitly or explicitly two classes of people, those who are capable of shaping their destinies and who thereby deserve their success, and those who are not, and who deserve nothing. This classification invariably places those who do not fit the dominant physical or cultural mold, women, people of color, the poor that disabled in the second category.”

As I was preparing for my manfluencers conversation, I was reading this and thinking, yes, that is exactly the problem with the Jordan Petersonian self-making framework. Your book is historical, for the most part, and people might approach it or think of it as a critique of celebrity culture. But actually, the things that I thought about most were fascism, Nazism, and Donald Trump. I wrote a whole biography of Donald Trump at one point in my life, so I’ve read everything he’s ever put his name on—not that he’s written because he’s never written a book, but he’s published plenty of books.

He has this philosophy that is basically: you want to be the top dog. Why? It’s never quite clear, but there is no alternative. Your job is to try and crush everyone else. Not to invoke the easy Nazi comparison, but I am struck by the similarities between that and the Hitlerian idea that you build strength and power for its own sake, for the sake of just becoming powerful. To what end? Is it to achieve the happiness, fulfillment, and enlightenment? Not really, no. It’s because you think that your destiny is just to be extremely powerful and to maximally control your own destiny.

Burton

I do agree with you. But I think that like one of the places that you can see this transition from the kind of dandy worship, before we get all the way to Hitler, which is a harder immediate sell, is looking at someone like Gabriele D’Annunzio, considered a kind of proto-fascist military leader, but really, he starts out as a dandy in the Wildean mold. His first novel is basically about a young aristocrat and all these love problems and clothing that he likes to wear. He’s a society journalist, and he becomes a poet. But at a certain point, he starts getting both political and personal traction as this kind of prophet of basically erotic excitement through violence. Italy is still a very new country, and he’s advocating for Italian military intervention, first in Italian-speaking lands part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, but also, then in World War I.

So much of his political identity, and why people are drawn to him, is that he’s this prophet of this primal magical age where men were men and women were women, and we were all like Greek battle soldiers. He makes up this cry that he says is the cry of Achilles in the Iliad, and it’s not—he gets people to do it. After World War I, he basically became an 18-month dictator of a disputed Italian-speaking city in what is now known as Croatia. He basically leads this military dictatorship because he’s a celebrity that can get people to do what he wants. There’s poetry readings and fireworks every night. It’s this vision of a personality cult he writes about this in his novels, which are very influenced by Nietzsche, about the self who must become a god, and part of being a self who is a god is making these sheeple do your bidding. They are part of the artistic production. And the model that he sets is hugely influential to Mussolini, who was a big admirer of his.

Although, I think people who want to defend D’Annunzio against being a proto-fascist do like to point out that he personally hated Mussolini and thought he was a dick. But this vision of the Italian fascism does come directly out of D’Annunzioian political Nietzscheanism. I won’t call it fascism—I’ll take the Fifth for D’Annunzio. But definitely, he is the inheritor of this 19th century aesthetic strain. He puts it into a political program, and that political program is influential. There is a direct lineage here.

Robinson

Yes. By the way, people should know that if they pick up this book, it’s not just a book of ideas, but of extremely fun historical anecdotes that you have found and will introduce people to characters that they didn’t know about, or things that they didn’t know about people they did know about, like Thomas Edison. Could we go through a couple of examples? Because in each chapter, you move through time and take a case study. I had never seen until I read your book—and I keep forgetting the guy’s name, who made the portrait of himself looking like Jesus—

Burton

Albrecht Dürer.

Robinson

I looked up the painting, and it’s so totally fascinating as a turning point. Because if we’re talking about the history of people coming to view themselves as gods, is this the first moment where a guy paints himself as God?

Burton

I believe that it is. It’s not the first self-portrait, but it’s the first self-portrait where the personality of the artist is highlighted in a particular way. Which is to say, this sort of tradition of painting yourself as an artist, which is already relatively new—the medieval artist traditionally is the anonymous artisan working for the glory of God to create something for a wider whole—you might, at most, paint yourself as a background character in a religious scene: Jesus is being crucified and there are a bunch of sad worshipers and one of them looks a little bit like you. There is precedent for that. But the idea of sort of painting yourself as a worthy subject, and especially in Dürer’s 1500 painting, he’s facing the viewer and has his hand up in a kind of reference to a vocation of the traditional way that Jesus in iconography would raise his hand. There’s an “A.D.” for Albrecht Dürer that also hints that it’s 1500 A.D.—anno domini. So, there’s this kind of real vision that the artist is a kind of divine being. That ties into a wider Renaissance trend, which is the kind of theorization of genius in a very particular way, or theorization of a certain what I would call self-maker, understood as a kind of demigod. That there are some people who are real live blood aristocrats. There are some people who are just whatever—they’re peasants—but then there’s a kind of person, the genius, often referred to as the true noble or someone who has true nobility. Someone whose personal qualities—their genius, their intellect, their moral qualities—earn them a certain kind of aristocracy. It’s sort of like they’re the exception that proves the rule. The way that they get theorized or understood is as rhetorically, not literally, demigods. They’re basically like bastard children. And of course, many of these geniuses, like da Vinci, literally were bastards. But a lot of the language is very much like: so technically, his father is so-and-so, but really, his father is God—really, his father is nature—the true parent, the true author. These people have some kind of direct and unmediated relationship with either the divine or nature, and it’s in sort of Renaissance Neoplatonic language and not very programmatic. There’s a lot of the goddess Fortune, but also the goddess Nature, but also God. Rhetorically, it is quite slippery. But the thing that is consistent is this idea that the metaphorical bastard has the unmediated relationship with God and nature that his legitimate, normal rhetorical brother doesn’t. The most famous example of this is actually not in Renaissance Italy, but around the same time in Shakespeare’s King Lear. Edmund, the bastard of the two children of the Earl of Gloucester, has this incredible soliloquy about standing up for bastards, and his bastardy is that he is born out of lust and desire, whereas his legitimate brother is born out of custom and duty. He is born in a boring marital bed—”Got ‘tween asleep and awake” is the way he dismissively refers to his brother’s conception, whereas he is the child of nature, but also, the child of desire because he’s illegitimate. This image of the self-maker—the bastard—as the person who creates their own destiny through being a child of desire, as opposed to the custom child, is a kind of model for all the self-making tradition, like Edmund is the ur-bastard of all self-makers.

Robinson

And when you say they’re “the image of the self maker,” I feel like image is so important to all of this. You are not just tracing a phenomenon in which people come to believe that they are and ought to be controlling their destinies and act accordingly, you are also tracing the rise of a particular kind of picture of themselves that people want to leave in the minds of others around them. So, a lot of the self-makers in the history of the self-made man and the influencer are not really self-made, but they are very skilled—I feel like you’ve mentioned Elon Musk here—in creating the picture of the great genius.

Burton

Absolutely. This is something that we find both in the kind of dandy European strain and then the American hard work strain. For every Horatio Alger narrative of bootstrapping your way to the top, you have a P.T. Barnum, an all-American hoaxer who realizes that people want a little bit of humbug and enjoy being fooled. Ultimately, something that kind of becomes part of both the American and European narratives of self-making is this idea that the smart, canny person can create their own reality. And again, there’s this figure of the con artist, the hoaxer—P.T. Barnum writing about humbug—but also there’s a novel called Vivian Gray from the Regency era, which was written anonymously and published in 1826. It’s the story of a kind of Beau Brummell-esque dandy, but who has a sneer for the world. He has contempt for everyone around him and no morality. It’s basically like a proto-House of Cards: he lies, cheats, and steals his way as he tries to advance socially. I find this hilarious: it is actually written under a pseudonym by Benjamin Disraeli, who would go on to become Prime Minister, and before he goes into politics, he is deeply aware of being a kind of outsider in a certain way because he’s Jewish, but he envisions, in this novel that becomes hugely scandalous, the self-maker as someone who can make society in his image where morality is secondary to being able to massage public opinion. And while it’s obviously a satirical book and not to be taken too seriously, it is, I think, a testament to this awareness that because everything rests on perception, part of self-making, as this tradition of determining one’s own destiny, involves shaping public perception, even if it’s “false”.

Robinson

Let me conclude here by asking you, are we trapped? Is this unavoidable? Has the mixture of Darwinism, Nietzsche, the abandonment or the loss of faith, and the rise of social media created a kind of toxic brew from which we will never escape? Or do you think, in our own time, we can free ourselves? As you say, there are things that we don’t want to necessarily sacrifice about this view that we can and should become who we want to be, and that we, as humans, deserve to be free to have fulfilling lives and personal aspirations, but without drifting into this view that the greatest good of all is to not be made at all by your society, surroundings, or nature, and to do all the making of yourselves as a god on earth.

Burton

I think we’re probably pretty trapped. I’m not overly optimistic. But I do think that, particularly for generations that have grown up on social media, we will see a more defined movement or subculture of people, Zoomers and younger, who haven’t grown up as content for their parents who are extremely online, and will desire to move away from it. Socially speaking, it is very hard to not be on social media, even in terms of living your life. It’s very hard not to walk around with a smartphone in your hand because you will need to scan it here and scan it there. But I think we will see a significant, but perhaps not culture shaping, minority of people making the active intentional decision to avoid that social media life as much as possible as a commitment.

Robinson

You must feel this because I feel it. You and I both, I guess, make a living as public intellectuals, in a certain sense. You must feel this pressure to package and brand yourself, and obviously, publishers now buy the author just as much as they buy the ideas in their book. When you do a book proposal, you have to say, this is my Instagram account and this is my marketing strategy. It horrifies me because I have to try and create a sellable identity to have a career.

Burton

I hate it. I like coming on podcasts. I’m enjoying talking to you very much. I like that part. And I actually think nonfiction is a little bit better in that regard because you still can talk about ideas in a way. My sense is that for fiction it’s even more about your personality, just from my own experience trying to promote both. But I always say I’ll know that I’ve truly made it when I can not have any public facing social media. When I can be offline. When I’m like one of those eminent older writers who you have to write by snail mail and perhaps their secretary will forward the letter to them. For me, that is what success is. A certain kind of privacy or not self-branding feels like a luxury good for an aspirational stage in my career.

Robinson

Yes. That’s why I feel like the ideal author is like Elena Ferrante, where it’s like if you can get it so that people will have to just appreciate the text, and they’re not allowed to know anything about the author and can’t factor that into their thoughts. Oh, how nice that would be.

Burton

Absolutely.

Transcript edited by Patrick Farnsworth. This conversation originally appeared on the Current Affairs podcast. It has been lightly edited for grammar and clarity.