How Anti-Homeless Sentiment Made Its Way Into Popular Cartoons

Cartoon depictions of the homeless increasingly reflect the hostility of today’s political leaders toward people on the streets. We’ve gone from images of charming hobos with bindles to zombies taking over cities.

If you consume any news at all, you’ve probably noticed that the United States is pathologically cruel to its homeless citizens. This May, the brutal killing of Jordan Neely—who was strangled to death, at the age of 30, simply because he was unhoused and shouting on the Manhattan subway—captured the national spotlight, but it was just one of many such cases of unprovoked violence. In January, two cops reportedly kidnapped a homeless man in Hialeah, Florida, drove him to an “isolated and dark location,” and beat him unconscious. That same month, art dealer Shannon Collier Gwin faced battery charges after he sprayed a homeless woman with a hose outside his San Francisco gallery, barking “Move! Move!” at her. (Predictably, Gwin got a lenient plea deal of just 35 hours of community service.) Elsewhere in the city, homeless San Franciscans have been attacked with chemical bear spray on at least eight occasions. Other assaults have been more impersonal but no less vicious. On July 14, the city of Houston abruptly closed its only public cooling center in the downtown area, potentially condemning anyone without shelter to suffer heatstroke in 90-degree weather. Among the property-owning class, the phenomenon of hostile architecture—sidewalks with spikes that stab anyone who tries to sleep, benches with iron bars, and the like—has become de rigueur. The widespread callousness and lack of compassion are both infuriating and hard to comprehend. How on Earth, we might ask, did things get this bad?

For answers, we can look to a surprising source: cartoons. Cartoons often rely on shared cultural assumptions and stereotypes for their humor, and you can tell a lot about how a society views social and political subjects from the way they’re represented in animated form. In the Chilean book How to Read Donald Duck, for example, Marxist writers Ariel Dorfman and Armand Mattelart argue that the globe-trotting adventures of classic Disney characters reflect the perspective of U.S. imperialism toward the rest of the world—in his comic strip incarnation, Donald is always visiting exotic new countries and rescuing hapless locals who hail him as a white (feathered) savior. (The book was banned by the Pinochet dictatorship; apparently, they were staunch defenders of the Duck.) Of course, this type of analysis can be done badly—the world has too many long-winded YouTube videos with titles like “The Secret Neoliberalism of Shrek 2”—but at its best, a political critique of cartoons can provide genuine insight. If we turn a critical eye on animated depictions of homelessness and how they’ve changed over time, we may learn something valuable about the growth and spread of anti-homeless ideology in the United States, and even find ways of combating it.

Looking back at older cartoons, one of the things that stands out immediately is the absence of negative attitudes toward the homeless. In fact, during the Golden Age of animation, creators seemed to have had a real affinity for the poor and unhoused, often placing their most iconic characters in that role. There’s a wonderful 1948 Warner Bros. short called “Riff Raffy Daffy,” in which Daffy Duck is looking for a place to sleep—first on a park bench, then a trash can, and finally a furniture display in a shop window—and has to dodge the harassment of the police, as represented by Porky Pig in a little blue uniform. (Literally, the cop is a pig!) Or, in the 1950 cartoon “Homeless Hare,” Bugs Bunny’s rabbit hole is destroyed by a new construction project, leading him to unleash his usual slapstick mayhem against the developers until they put it back. In these cartoons, homelessness is something inflicted on people by outside forces—gentrification and the real estate business, in Bugs’ case—and something which can be successfully resisted. Even Disney cast a homeless dog as a romantic lead in 1955’s Lady and the Tramp, contrasting Lady’s sheltered naivety with Tramp’s superior knowledge of the world. The title invokes the memory of Charlie Chaplin’s “Tramp” films, which similarly brought dignity and humanity to the role of a homeless man. (Bugs Bunny, too, takes inspiration from Chaplin, and multiple Warner animators have drawn him as the Tramp.) In 1961, Hanna-Barbera’s profoundly underrated Top Cat followed the adventures of a gang of wisecracking Manhattan alley cats, who, like Daffy, are always outwitting a meddling policeman. At worst, classic cartoons may trivialize the suffering and danger associated with homelessness—there’s a certain recurring image of the carefree hobo carrying a bindle, which paints the whole subject in a romanticized light—but the homeless themselves are rarely disparaged or made the butt of the joke. Quite the opposite.

In light of the historical context, we can make some educated guesses about how and why these early, sympathetic portrayals came to be. In the ’50s and ’60s, the cultural memory of the Great Depression was still fresh, and a significant number of people—both in the cartoon-viewing audience and the creative industries—would have either experienced homelessness firsthand during the ’30s or had friends and family members who did. Cartoons themselves (shown in movie theaters before the advent of home TV) gained popularity as a cheap form of entertainment for working-class audiences, and many of the pioneering Hollywood animators came from economically precarious backgrounds. Warner Bros. animator Chuck Jones recalled in a 1993 interview:

I came out of art school in 1931, right in the worst of the Depression, two years before Franklin Roosevelt came in. The whole United States was flat. To expect to get a job when three out of every ten people were unemployed was ridiculous, particularly for a kid without any experience in anything. I had worked my way through art school by being a janitor, … and I wasn’t sure I was capable.

Jones’ experience was typical of the era. Before becoming an animator, William Hanna of Hanna-Barbera fame had actually lost his job as an engineer to the Depression and resorted to working in a car wash to get by. At the time, people who hadn’t experienced some form of financial hardship, up to and including the loss of their homes, were the exception rather than the rule. As a result, there was a common understanding—as there’s beginning to be again, in the COVID era—that poverty and destitution can happen to anyone, at any time, through no fault of their own. It’s no surprise, then, that this historical moment was reflected and embodied by the artists it produced. To paraphrase a famous Marx line: Men make their own cartoons, but they do not make them as they please; they do not make them under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past.

With succeeding decades, though, the narrative changed. The ’70s and ’80s saw the dismantling of the New Deal economic order, and with it, the idea that poverty and homelessness were shared social problems at all. Instead, the pernicious “bootstrap” doctrine, always present in American discourse, intensified to new extremes. Free-market ideology became a dominant force: if anyone was suffering economically, it was their own fault for failing to hustle hard enough. In one infamous interview, Ronald Reagan aimed a rhetorical blowtorch at the homeless, insisting that they were responsible for their own fates:

What we have found in this country, and maybe we’re more aware of it now, is one problem that we’ve had, even in the best of times, and that is the people who are sleeping on the grates, the homeless who are homeless, you might say, by choice.

What a bald-faced lie! Reagan, still the patron saint of certain branches of the GOP, had the nerve to look directly into a camera and say that homeless people wanted to sleep on the street. In reality, it was Reagan’s own choices that forced them to. During his tenure as president, the U.S. government slashed spending on public housing programs from $26 billion to just $8 billion and gutted welfare under the pretext of reform, using the racist stereotype of the “welfare queen” to justify financial austerity. Rather than being seen as neighbors and fellow citizens, the homeless were recast as an undesirable subclass of humanity, lazy and morally unworthy of having their basic needs met. The United States had a new mythology, and it was a brutal one, soon to be disseminated throughout the nation’s cultural products.

It took a few years, but cartoons caught up to the Reaganite turn. In episodes from the ’90s and early 2000s, there’s a palpable shift in the way homeless characters appear compared to earlier decades. The perspective is different: we’re now seeing them through the eyes of comfortably housed characters, rather than their own. Often they don’t even get proper names. In a 1996 episode of Hey Arnold!, we’re introduced to a man known only as “Grubby” who seems to live in the subway and yells at passengers to “Get out of my house!” In a cutaway gag from Family Guy (the show is ongoing since 1999), Peter Griffin says he hates his job “almost as much as I hate homeless people asking me for money,” before mocking a homeless man he calls “Raggy.” And in King of the Hill (1997-2010), there’s a recurring character called “Spongy” who can be seen scrounging for cans to recycle or eating cat food. Grubby, raggy, and spongy. Adjectives, not nouns. This is what the United States now thinks of its homeless.

Notably, King of the Hill actually calls out Reaganomics as a key factor, with Spongy saying that he’s “been here since Ronald Reagan kicked me out of my mental hospital” in a 2006 episode. He’s referencing the repeal of the Mental Health Systems Act of 1980, which eliminated thousands of hospital beds and left patients struggling with mental illness nowhere to go but the street. But at the same time, the show has patriarch Hank Hill deliver a bunch of self-righteous platitudes about the virtue of hard work and how “if you’re relying on handouts, you’re not in control of your life.” Somewhere in hell, old Ronnie smiles.

This trajectory leads us, perhaps inevitably, to SpongeBob SquarePants. Since the character’s debut in 1999, SpongeBob has taken on the cultural role that Bugs Bunny and Mickey Mouse occupied in the 20th century. He’s not only a universally recognizable icon of animation, but of American pop culture more broadly. As early as 2009, SpongeBob was the most popular children’s program in 15 major Chinese cities, despite being banned from broadcasting before 9 p.m. When the U.S. assassinated general Qasem Soleimani in 2020, an Iranian cleric mockingly wondered if Iran should “take out” SpongeBob in return; that’s how prominent the series has become worldwide. While it might seem faintly silly to talk about the political dimensions of SpongeBob cartoons, this dominant cultural status makes the series unusually significant to understanding U.S. ideology. If there’s a common cliché, trope, or assumption in American culture, it’s probably replicated somewhere in SpongeBob SquarePants, and from there, spreads outward to a generation raised on Nickelodeon. What’s more, the series often riffs on topics like money, labor, and exploitation, with overtly political episodes like “Squid on Strike,” where SpongeBob and his coworker Squidward organize a protest for better wages. In the 2002 episode “Can You Spare a Dime?”, meanwhile, the show delves explicitly into the issue of homelessness. In a sparse ten minutes, it provides a valuable case study in how reactionary talking points can manifest themselves in the most unexpected places.

“Can You Spare a Dime?” is, to put it mildly, tonally bizarre. In its opening moments, Squidward gets accused of stealing a dime by his comically greedy boss, Mr. Krabs, and quits his job in a fit of outrage. We then flash forward to see Squidward, now bedraggled and unshaven, living in a cardboard box on the street and begging for change. He looks genuinely miserable, and it’s hard not to feel sorry for him, even as the show makes absurd jokes about his predicament. (He apparently tried to make a living as an artist, but no one bought his paintings, so he “had to eat them.”) Mercifully, the ever-cheerful SpongeBob gives Squidward a place to stay—but the moment he’s safely off the street, Squidward turns from a sympathetic victim of circumstance into a lazy, entitled freeloader, straight out of a Reagan speech. He makes no effort to find work and loafs around SpongeBob’s house for ages, as indicated by the series’ trademark title cards: “THREE WEEKS LATER,” “MANY MONTHS LATER,” and “SO MUCH LATER THAT THE OLD NARRATOR GOT TIRED OF WAITING AND THEY HAD TO HIRE A NEW ONE.” All the while, Squidward expects SpongeBob to cater to his every whim, making increasingly ridiculous demands for snacks, drinks, massages, and entertainment. To use the ugly Reaganite term, he has become a welfare queen (or king), leeching off the hard work and misguided benevolence of others. Eventually, an exasperated SpongeBob writes “GET A JOB” in his alphabet soup, before shoving him (bed and all) back to work at the Krusty Krab.

For what it’s worth, all of this basically works as comedy. The unsavory political subtext can be overlooked if you view the episode as a reflection of Squidward’s character traits in particular and not a commentary on homeless or jobless people in general. Canonically, Squidward can be a bit of a jerk. Still, looking deeper, there’s a definite streak of Reaganism running through the plot. In the first place, Squidward’s homelessness is essentially his own doing, since he could have put up with Mr. Krabs’ ranting and raving about the missing dime and kept his job. He is, as Reagan put it, “homeless by choice.” Importantly, though, Reagan and his acolytes never provided any actual evidence that “homelessness by choice” exists on a large scale. The whole concept should be interrogated and challenged, but instead it has wormed its way into the fabric of American culture to the extent that it pops up in cartoons about talking sea creatures. Not only this, but “Can You Spare a Dime?” frames Squidward’s decision to quit as impulsive and ill-advised, rather than a perfectly sensible reaction to being berated in the workplace for something he hasn’t done. The episode resolves by returning him, suitably chastised, to a job where his boss shouts at him. In one sense, this is insightful, showing how the threat of homelessness and starvation is used as a weapon to keep workers in line. For the show’s young audience, though, it’s completely the wrong message. If working people are to have any dignity, the Mr. Krabses of the world need to be defied, not appeased.

Worst of all, though, the episode suggests that homelessness can be solved on an individual basis if the people in question simply stop being lazy and “GET A JOB.” This is the biggest myth of all. In 2021, a statistical analysis by the University of Chicago found that 53 percent of people in homeless shelters, and 40.4 percent of unsheltered people, do have jobs. The problem is that their wages are too low, and rents are too high. According to statistics from the same year, it’s impossible for someone working a full-time, minimum-wage job to afford a single-bedroom apartment in 93 percent of U.S. counties, and there are no states in which someone can rent a two-bedroom space on the current federal minimum wage of $7.25 per hour. In other words, homelessness has little or nothing to do with personal responsibility, or lack thereof. It’s a consequence of large-scale economic decisions made by landlords and bosses. It’s not that the creators of SpongeBob SquarePants necessarily intended to push bourgeois propaganda on their viewers, of course. They were just trying to make the funniest cartoon they could from the premise “Squidward becomes homeless.” Rather, these free-market narratives about housing and labor have become so pervasive that, without a conscious effort, it’s hard for a viewer to perceive them as ideological at all.

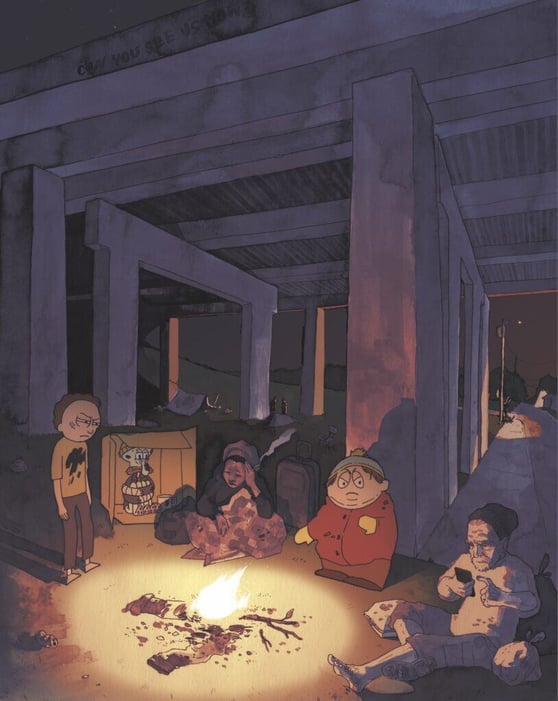

Things get weirder on South Park (ongoing since 1997), with the 2007 episode “Night of the Living Homeless.” A parody of George Romero’s zombie movies, the episode sees South Park overrun by dozens of homeless people who appear suddenly overnight, shambling around the streets and muttering “chaaange” in the stupefied groans usually reserved for “braaains.” When Kyle, Stan, Kenny, and Cartman investigate, they discover that the nearby town of Evergreen has exported all of its homeless to South Park, having received them unexpectedly from San Antonio, Texas, in the first place. So the boys rig up a Mad Max-style armored bus and blast a parody version of Tupac Shakur’s “California Love” (“In the city, city of Santa Monica / Lots of rich people, giving change to the homeless”) from the loudspeakers. Thus equipped, they lure the crowd away to yet another new city, where the cycle will presumably begin again.

In a recent article, Current Affairs film critic Ciara Moloney described South Park’s creators, Trey Parker and Matt Stone, as “dead right about half the time” and “about as wrong (as are all principled libertarians) as you can be” the other half. This is a perfect description of “Night of the Living Homeless.” In certain moments, the episode skewers wealthy liberals’ patronizing non-solutions for the problem of poverty, as seen when a member of the South Park town council suggests that “we could give the homeless all designer sleeping bags and makeovers. At least that way they’d be pleasant to look at.” Or, as Stan’s dad Randy bizarrely suggests, they could “turn the homeless into tires.” “That’s like recycling,” another character chimes in. It’s not hard to imagine a politician like Portland Mayor Ted Wheeler—known for his sweeps of homeless encampments—proposing ideas in this sublimely useless vein. If the episode exaggerates, it isn’t by a lot.

Then, too, the practice of shuffling homeless people from city to city without actually addressing their needs is a real one. As a 2017 Guardian investigation detailed, cities like San Francisco “view free bus tickets as a cheap and effective way of cutting their homeless populations” and issued at least 21,000 such tickets in the years 2011-2016. But while the practice is convenient for city administrators, it’s devastating to the actual homeless people involved, who find it difficult to restart their lives from scratch in an unfamiliar place—and who are often banned, for life, from returning to shelters in their original cities as a precondition. (“They stabbed me in the back is what they did,” reflected one traveler interviewed by the Guardian, and he’s not wrong.)

When it comes to its main characters, South Park has two basic modes: there are the episodes where the boys are sharp-eyed critics calling out hypocrisy and the episodes where they’re just selfish assholes like everyone else in town. With its ending, “Night of the Living Homeless” puts them firmly in asshole mode, and, by doing so, sheds light on a deeply inhumane real-world phenomenon.

This still leaves the “as wrong as you can be” half, though, and it’s linked directly to the episode’s use of zombie imagery. On the political right, equating homeless people with zombies has become something of a cliché. In 2020, GOP Representative Devin Nunes said that “the situation out here in California with the homeless population” reminded him of “zombie apocalypse.” In 2022, Dr. Mehmet Oz described Philadelphia’s homeless residents as “addicts walking like zombies into the street” during his abortive Senate campaign. In 2023, Fox News host Jesse Watters declared that “the zombies are taking over” Portland because there are tent encampments there, billionaire Michael Moritz described neighborhoods with a large homeless population as “zombie zones,” and Elon Musk repeated the “zombie apocalypse” description about downtown San Francisco. The rhetoric is chilling to hear because it dehumanizes homeless people in a very direct and blatant way. By definition, a zombie is an inhuman monster, a thing to be destroyed rather than a person to be engaged with. The least subtle of the bunch, Watters explicitly advocates for violence against the homeless, saying that the appropriate solution would be to “get tough and clean stuff up and knock heads together and institutionalize people and clean up the streets.” This is the sort of thing that becomes easy to justify once you no longer see certain types of people as fully human. The truly obscene part of “Night of the Living Homeless” isn’t any particularly crass joke, but the way the episode simply accepts the framing of the homeless as a monstrous threat. It lacks a crucial scene, one which might reveal that South Park’s residents just perceive—ignorantly—their homeless visitors as the undead. In the text we get, the homeless actually are zombies, and the whole narrative revolves around the need to get rid of them by whatever means are available. Beyond Reaganism, we’ve now crept into something that could be called proto-fascist.

Similarly worrying themes pop up again in Rick and Morty, with the 2013 episode “Anatomy Park.” (Yes, Rick and Morty has been going for ten years. I feel old too.) Here, Rick Sanchez—the show’s mercurial genius/insufferable egomaniac protagonist—brings Ruben, a homeless man dressed as Santa Claus, home to his family for Christmas dinner. However, what seems like an act of sincere kindness is soon revealed as something much darker: Rick has built a miniature theme park inside Ruben’s body, where visitors can be shrunk down to microscopic size and go on rides like “Spleen Mountain” and “Pirates of the Pancreas.” The rest of the episode turns into a Jurassic Park parody, as Morty—Rick’s grandson and longsuffering sidekick—has to shrink down, explore Anatomy Park, and dodge various infectious diseases that have run rampant through Ruben’s system. Eventually, for complicated reasons, Ruben dies, expands to gargantuan size, and explodes, showering the entire continental United States in blood and offal. (Did I mention that this is a Christmas episode?)

Clearly, there’s a lot going on here. Rick and Morty has always been a slightly mean-spirited show—one early episode sees Rick launch into an enthusiastic defense of the r-slur, for example—but “Anatomy Park” might be the furthest it ever goes into purposely offensive shock humor. As viewers, we’re expected to find it funny that Rick has conducted hideous human experiments on a homeless man (who seems barely aware of his surroundings), and later that he desecrates his corpse, shoving a big red bundle of dynamite into Ruben’s abdomen in order to free Morty. And the sick part is, it almost works. From a purely technical perspective, “Anatomy Park” is a well-constructed script, and concepts like “Pirates of the Pancreas” are so absurd that it’s hard not to laugh at them. But the episode only functions comedically if you grant Ruben no humanity whatsoever and view him simply as a prop. If you think for a second about what it would be like to actually be him, the whole thing just becomes terribly depressing. In its basic structure, the cartoon relies on its audience to treat its homeless character as a disposable human being, interesting only insofar as he furthers the plot.

The really fascinating part of all this—and something that I only realized after looking at the episode’s script online—is that the word “homeless” is never actually spoken. It’s in the Wikipedia and IMDb listings, and in contemporary reviews, but not in “Anatomy Park” itself. Instead, Ruben is legible as a homeless character solely from visual cues. He has sweat-stained clothing, a ragged beard, a string of drool on his lower lip, and so on. With a few variations, they’re the same visual markers that define the homeless Squidward in “Can You Spare a Dime?” or characters like Grubby in Hey Arnold! But this shorthand is troubling, because it implicitly associates homeless people with dirt and filth. The Rick and Morty animators understand that, when their viewers see a character who looks a bit unhygienic, their first thought will be “Oh, that’s a homeless guy.” They don’t need to spell it out, because the prejudice is already baked in.

In turn, the episode’s heavy reliance on gross-out humor reflects a belief that Ruben and people like him are, fundamentally, gross. As it goes along, “Anatomy Park” reveals that Ruben is an alcoholic (he has a “Haunted Liver”) and carries a full menagerie of viruses and bacteria, including gonorrhea, hepatitis A and C, tuberculosis, E. Coli, and even the bubonic plague. These are drawn as big fanged monsters, the dinosaurs in the Jurassic Park analogy, who chase the miniaturized Morty around. In this way, Ruben’s homelessness is equated not only with dirtiness, but with the threat of disease. Ruben himself is essentially a contagion. Historically, that’s always been a dangerous association to make about particular types of people. Like the zombie metaphor, it’s a form of dehumanization, and when it becomes common enough, it can lead directly to violence against those perceived as carriers of illness. Recall Jesse Kelly, fuming that people need to “clean up the streets” by “knocking heads together.” Recall Mr. Gwin and his hose. The operative word is clean, and it springs from the conviction that the homeless are unclean, a disease on the body politic. From there, it’s one short, tragic step to Jordan Neely lying dead on a subway floor.

There is an alternative. As we’ve seen, cartoons—like every cultural artifact—shape our understanding of the world, but they’re also shaped by the material world around them. As the politics of housing shift, so do the cultural representations of unhoused people. Degrading stereotypes about the homeless have a rich environment to thrive when the dominant political narratives are all about personal responsibility, the free market, and bootstraps. But another, entirely opposed form of politics is rising. With the growth of the “Housing First” movement, there’s a new understanding that you solve homelessness by simply providing homes, markets be damned. With increasing demands for rent control and tenant unions, people are banding together to fight the domination of landlords and real estate investors and striking at the heart of the inequality that generates homelessness in the first place. Slowly, but inexorably, the scales are falling from our eyes. When the children of the future look back on our popular culture, they’ll shudder to think we could ever have accepted things as they are now. Indeed, they’ll find it hard to believe such a thing as “homelessness” ever existed.