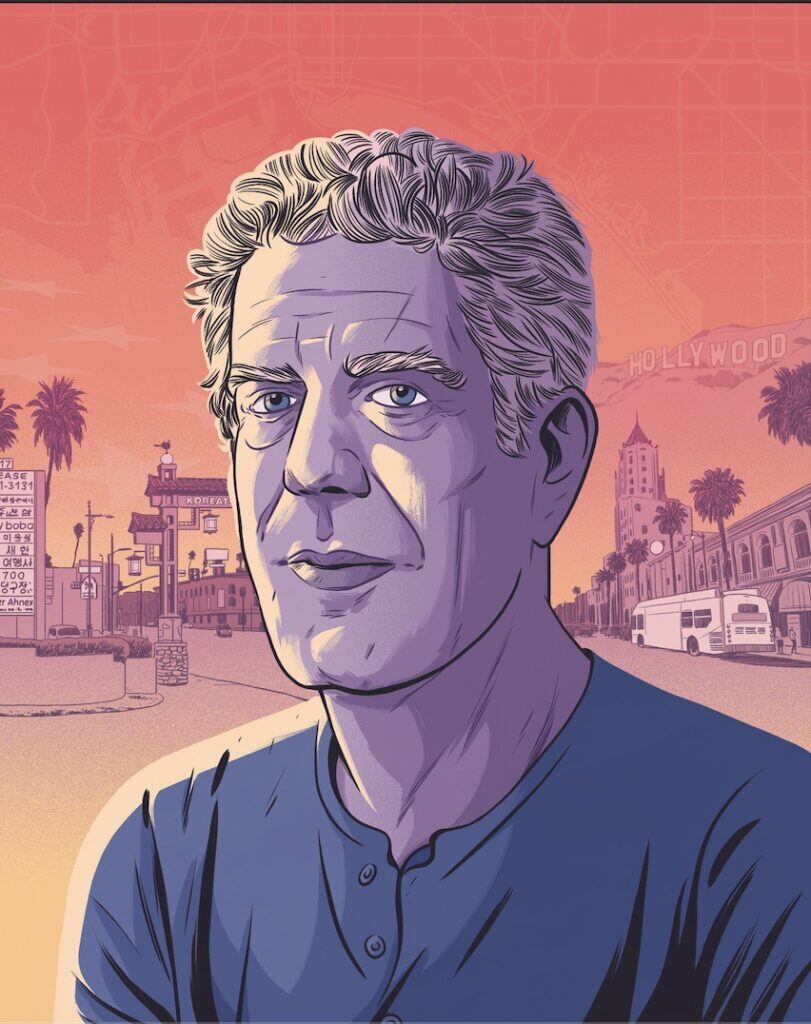

Finding Los Angeles with Anthony Bourdain

How Bourdain’s work reoriented one writer’s engagement with people and places around him.

“We might wonder if the movies have ever really depicted Los Angeles.”

Thom Andersen, Los Angeles Plays Itself

When it comes down to it, I’m a pretty boring traveler. I finally realized this when my neighbors shared plans to drive a motorcycle one thousand miles up the Pacific Coast Highway with two hiking backpacks strapped to their sides to soak in the gorgeous California and Oregon landscapes before flying to Nepal and backpacking through the Himalayas for three weeks. The only proof I have of a comparably adventurous spirit is a short documentary about a time I spent in Morocco, which I completed for an undergraduate course and have since done my best to remove any trace of from the internet. For one segment, I assembled some footage of Chefchaouen, a gorgeous blue-painted city in the Rif Mountains, and paired it with a quote from Paul Bowles’ The Sheltering Sky, thinking this would give the images more substance than beauty alone could convey. The quote was this:

“Whereas the tourist generally hurries back home at the end of a few weeks or months, the traveler, belonging no more to one place than to the next, moves slowly, over periods of years, from one part of the Earth to another. Indeed, he would have found it difficult to tell, among the many places he had lived, precisely where it was he had felt most at home.”

Even though my trip only lasted about 10 days—putting me squarely in the “tourist” category—I thought the quote accomplished something; it conveyed a level of seriousness that would separate me from the stereotypically aloof American waving a selfie-stick around UNESCO World Heritage sites and disrupting photos of awe-inspiring landmarks with one’s disembodied head. But when I revisited the project recently, what I found was more embarrassing than a folder full of selfies in the Marrakech markets. Not only had I not captured any of the wonderful people I’d met in Chefchaouen, but the monotone delivery and intellectual posturing of my voiceover track had drained all the pleasure out of the footage. Still, I couldn’t be too hard on myself: this all took place well before I discovered Anthony Bourdain and his show Parts Unknown.

My obsession with the writer and travel TV host began one year after my Morocco trip, when I was staying with a friend in Los Angeles. The “Vietnam” episode was playing on the Vizio in his living room, and I caught it right at the following scene : the one of an exuberant Bourdain sitting on a “low plastic stool” with a cold local beer and a bowl of clam rice while the night life of Hue—scooters, street carts, steaming pots and pans—poured into the mise-en-scène. When he punctuated that segment with the line, “Fellow travelers, this is what you want. This is what you need. This is the path to true happiness and wisdom,” I found myself hooked.

I had been in Los Angeles that day for an interview with a major network, a position in their early-career program that I was hoping to use as a stepping stone to more creative roles in “the industry,” or, as it’s known on BoJack Horseman, “Hollywoo.” Looking back, I can see why I would have been attracted to the entertainment industry; like many suburbanites with unlimited cable and a flatscreen television, I’d formed my identity around preferences for certain American TV shows. Yet, during the thousands of hours I’d spent in front of a screen, I’d never come across Anthony Bourdain. I like to think if I had, I would have skipped the whole predictable journey out west and simply let my imagination expand outwards to lesser-known places. But alas, one week after my first exposure to Parts Unknown, I received a job offer and moved to Studio City to begin work as a lowly “Hollywoo” assistant.

For a time, I was quite happy to have access to that world, though I was slowly discovering what a tremendous bore the “entertainment” industry could be. Minus my coworkers’ inflated sense of the value they were adding to society (i.e., quality control for return-on-investment-friendly film and television intellectual property) and the gloss of celebrity proximity, the place was remarkably similar to other corporate environments I’d worked in: the productivity mantras, the rote conference room meetings, and the bureaucracy. It didn’t help that in the evenings and weekends outside of the office, I was also learning what an overwhelming and dysfunctional city Los Angeles could be. The trendy brunch spots and hipster thrift shops abutted by blue tarp shelters offered a harsh contrast to the paradisiacal images I’d been conditioned to associate with the place thanks, in large part, to the industry I’d taken up work in. Even in darker films like Chinatown (1974), one could not deny the beauty of Echo Park Lake, the Central Valley orange groves, or mission-style bungalow courts.

To process the gap between expectation and reality, I devoured all the Bourdain content I could get my hands on. I tore through Kitchen Confidential, the memoir that made him famous overnight in May 2000, then worked backwards through Parts Unknown (2013-2018) and his web series Raw Craft (2015-2017), followed by his eight-year Travel channel run with No Reservations (2005-2012) and The Layover (2011-2013), followed by his foray into television, A Cook’s Tour (2002-2003). Then I scoured YouTube for interviews. There was more content than it felt possible to exhaust, yet I consumed all of it—sometimes deeply, other times mindlessly, and often addictively. I enjoyed Bourdain’s voice to the point that I felt his shows transcended criticism. They were raw in a way that excused all of their flaws, even when Bourdain, for example, indulged in navel-gazing segments about his jiujitsu practice for a substantial portion of an episode that was otherwise about Silicon Valley’s moneyed invasion of the greater San Francisco Bay Area and the locals who were gradually being displaced by it.

The show and the man were inseparable, so it seemed to me that if you loved the man, you loved the show, even as his constant presence and vulnerability occasionally interfered with the otherwise inquisitive and outward reaching nature of the series. A little self-indulgence could be a good thing. Take the episode in which he travels through Quebec with truffle-loving chefs Dave McMillan and Fred Morin. There’s a scene in which the trio go ice fishing then retreat to a tiny cabin atop the frozen lake to enjoy top-shelf white burgundy whilst downing Glacier Bay oysters and discussing tableware esoterica. Bourdain’s voiceover comes in as McMillan serves the main course:

“What’s that you ask? An iconic Escoffier-era classic of gastronomy? … The devilishly difficult, lièvre à la royale: a boneless wild hare in a sauce of its own blood, a generous heaping of fresh black truffle, garnished with thick slabs of foie gras, seared directly on the top of the cabin’s wood stove.”

Later, he puts the cherry (or shaved truffle) on top when he posits, “Is there a billionaire or a despot anywhere on Earth who, at this precise moment, is eating better than us?” As far as food cinema goes, I would rank it right up there with the Goodfellas scene in which Henry Hill and his fellow inmates assemble a homemade pasta sauce to the tune of Bobby Darin’s “Somewhere Beyond the Sea.” The best of Parts Unknown often warranted such comparisons as week after week the cinematography, the characters, and the editing added up to one of the most delectable viewing experiences on television.

But of course, the show wasn’t all gateau marjolaine and warm wool sweaters. For every episode with an auteur chef—Paul Bocuse, René Redzepi, Masa Takayama, to name a few—there were many others that dealt with serious political issues, including extreme poverty, gentrification, the aftermath of colonialism, the impact of U.S. military presence, climate change, intractable religious conflict, and political oppression. (Bourdain, who got his start in the food industry as a dishwasher and line cook working alongside immigrants, was also outspoken about how crucial immigrant labor is to the restaurant industry. As he once said, in response to claims that Mexicans were stealing jobs from Americans, “[I]n two decades as a chef and employer, I never had one American kid walk in my door and apply for a dishwashing job, a porter’s position or even a job as prep cook.”) Despite Bourdain’s popular associations with the culinary world and his appreciation of cuisines ranging from the Lyonnaise dishes of legendary chef Paul Bocuse to the “deranged” fast food spaghetti at the Filipino chain Jollibee, food was often just an excuse to explore these issues across the dinner table. Sometimes it was entirely peripheral.

His “Laos” episode in season nine of Parts Unknown is a prime example. It opens with footage of lush mountains coated in the pink and purple light of dawn as Bourdain’s voiceover comes in to remind us of the American missions that devastated this quaint landscape 50 years earlier, confronting us with the fact that more bombs were dropped on Laos than on Germany and Japan in World War II combined, all in an effort to halt the spread of communism. The rest of the episode is primarily concerned with showing the impact of this horrific legacy on the Laotian people, more than 20,000 of whom have been killed or maimed by unexploded ordnance since the war’s end.

Over the course of 40 minutes, Bourdain eats with a local journalist, a hotel owner, and a former soldier (discussing topics ranging from the remnants of French imperialism to Obama’s aid for the removal of unexploded bombs), interviews a bomb removal squad working on the monumental task of safely detonating 80 million unexploded ordnance, and, eventually, shares a meal with a man who grew up during the war. When the man shows Bourdain scars from a bomb that injured him when he was a child, Bourdain asks him if he has any anger toward the U.S. as a result of this experience. Remarkably, the man does not seem angry and recalls the doctors at an American hospital who provided free medical care for his wounds. Then Bourdain, not quite satisfied with the man’s answer, asks a more difficult question: “All the bombing, all the suffering, all the death… what did [you] think it was all for?” The man responds, “I don’t know what the reason is.”

This is the final line we are left to contemplate in the last five minutes of the episode as footage of Boun Ork Phansa—a festival marking the end of Buddhist Lent, described by Bourdain as “a symbolic casting away of [one’s] sins”—plays out. The dusk shots of Laotians launching fire lanterns down the Mekong river—some crafted in the shapes of boats and dragons, others as small candles—are beautiful to witness, but more so an opportunity for the audience to quietly consider the impact of U.S. foreign policy on the people gathered around the river. It gives the viewer space to ask questions like: What was the point of this secret war? What responsibilities do Americans have toward Laotians? Are similar atrocities being carried out by the American military today?

In his memoir, In the Weeds: Around the World and Behind the Scenes with Anthony Bourdain, Tom Vitale (Parts Unknown director) reveals this open-ended, confrontational approach to be a trademark of Bourdain’s style. There was nothing Bourdain despised more than “competent” or “workman-like” storytelling, and he often pushed the envelope to avoid anything resembling an easy news reporter-esque summation of his travels. One anecdote Vitale relays about editing the footage for the Madagascar episode with Darren Aronofsky reveals the attention Bourdain paid to the aesthetic limitations of his television format.

When their first edit of the episode hits a speed bump, Bourdain suggests Vitale fix the ending by repeating a scene from earlier in the show: a moment when Bourdain and Aronofsky get food at a train stop in the middle of the country. Vitale says he initially pushed back at this suggestion: “Doesn’t it kind of needlessly distract from the very serious issues we bring in the show and instead call attention to us?” To which Bourdain responds:

“Exactly. What do we include, what do we choose to leave out? Either way it’s our choice. It’s about the moral quandary of travel and white privilege. The camera is a liar. Drawing attention to it calls into question our own reliability and shows our hands aren’t clean. I want to show how manipulative even ‘honest, tell it like it is’ TV can be.”

In the first iteration of the scene, we are told that the train station is their only food stop on their 18-hour journey. Bourdain and Aronofsky are hungry when they arrive, but when they find most of the serving platters picked over and a number of skinny children gathering about their waists, their priorities change. They buy what they can and hand it out before the train departs for their final destination. All of this footage is presented in a matter-of-fact way, acknowledging the apparent poverty and hunger without dwelling on it at length. We get the impression that this sort of scene is not uncommon in Madagascar. But at the end of the episode, when Bourdain asks Aronofsky how he would have depicted their train stop experience, a second version of the scene plays that offers an unsettling juxtaposition to Bourdain’s more reserved take. We see more fighting over food, more children begging along the sides of the train, and new close-ups on the weapons of police standing nearby, and we hear shouting and bickering that was less apparent in the previous edit.

The juxtaposed edits are startling because they reveal how poverty, while commonplace, puts people in dangerous situations. There is no proselytizing in this depiction, only an admission of the limitations of the men as storytellers that confronts the audience with images of a country that they, more than likely, only ever associate with a colorful animated film of the same name. Of course, Bourdain’s aesthetic prowess was hardly a solution to the very real problems affecting Madagascar, but finding solutions to these problems was never the point of Parts Unknown. The point was to reveal the impact of larger issues like poverty and environmental devastation on places like Madagascar, to talk with the people there and see what they were hoping (or planning) for the future of their country, and to make those images and conversations more personal for an audience that otherwise might live in ignorance of these issues.

But even when Bourdain more or less accomplished the impossible task of making compelling TV out of heavy subject matter, there were still ethical questions that lingered long after an episode aired. What impact did his show have on a place? In the “Queens” episode, he sits down to a meal with Sarah Khan, a local food journalist known for her remarkable reporting on the borough, and asks her if she ever worries that by reporting on these communities she is helping to destroy them. When she responds, “absolutely,” Bourdain admits he feels the same about his own work—which, as the Daily Beast noted in 2018, has put many a restaurant on the map. In some episodes, Bourdain withheld the names of restaurants to protect them from too much attention from his audience or other would-be tourists.1

Making episodes that were respectful of the people he met, mindful of the show’s footprint, and aesthetically ambitious while grounded in his Western point of view, was a complicated task that weighed on him heavily. And when a shoot fell short of his storytelling values, he did not hide it from his audience. The Sicily episode is a good example of this. Also, in light of his suicide, it’s one of the more difficult episodes to revisit today.

Early in the trip, Bourdain’s Sicilian guide, Turin, takes him on an octopus fishing excursion off the coast of Catania. After Bourdain throws on his snorkeling gear and hops in the water, Turin decides to surprise him with some producing of his own, tossing several dead octopodes over the side of the boat to create an illusion of a success for the cameras, which, as any follower of the series might have guessed, does not sit well with Bourdain. The scene ends on an image of him floating amongst the withering cephalopods as his voiceover recounts the intense depression he spiraled into: “I’ve never had a nervous breakdown before, but I tell you from the bottom of my heart, something fell apart down there, and it took a long, long time after the end of this damn episode to recover.”

According to a post-episode interview, after the snorkeling excursion, he abandoned the shoot and headed to a local bar where he spent the afternoon drinking eighteen negronis, which explains why he’s blackout drunk in the following dinner scene. In voiceover, he admits he recalls nothing of the table conversation—a reality that becomes more and more apparent with every disapproving glare from his dining companions (the octopus tosser and his wife). Still, his breakdown comes across as somewhat sudden and confusing; the progression from fishing excursion Bourdain to dead-eye drunk Bourdain is jarring. I remember rewinding the episode the first time just to make sure I didn’t miss what had actually happened or why it was so upsetting to him. But it turns out my first impression was correct: absolute despair over a cheap trick.

At the time, I read the scene as an example of television’s inability to capture interiority even with the most introspective and compelling voiceover commentary imaginable. Given what I’ve learned about depression over the years, I think that takeaway was misguided. The TV depiction wasn’t flawed; Bourdain was. But my impression at the time nevertheless allowed me to overlook Bourdain’s reaction and justify it as a more extreme feature of his character: a consequence of the standard to which he held the show instead of a symptom of a depressive personality.

As Charles Leerhsen observes in his “unauthorized” biography Down and Out in Paradise: The Life of Anthony Bourdain:

“[Tony] often said he hated the word ‘authentic’—his nearly two decades of world traveling having taught him the futility of striving for the unalloyed version of anything—but on a personal level, authenticity, in the sense of being the real thing and not a pretender, was his lifelong preoccupation.”

No doubt Bourdain’s preoccupation with being the “real thing” frequently manifested as a search for the “real thing[s]” that made every place he visited unique. The “real thing” could mean many things, from the overlooked legacy of America’s secret war in Laos to the absurdly precious dining habits of two French-Canadian chefs, but what the show’s many subjects had in common was the search that lead to the “real thing”: sharing meals with people around the world that lead to conversations that revealed some essential truths about a place according to the people who lived there. Unfortunately, one phony fishing excursion aimed solely at entertaining CNN viewers was a clear violation of the honest and unfiltered approach he took so seriously.

But it wasn’t just the affront to the integrity of his process that set him off. It was also his struggle with depression, a struggle that anyone who read or watched closely enough could spot throughout his television run. His depressive tendency was even on display in an otherwise lighthearted Conan O’Brien interview in which he recounted an underwhelming meal at an airport Johnny Rockets that sent him into a three-day depression. But even with instances this glaring, I suppose I was caught up enough in what the show meant to me that I had overlooked what it did to him. His voice had become my escape from the phoniness of the corporate world I’d been groomed for and a catalyst for a new worldview. If anything, my feelings leaned toward envy.

Over the past five years, many of the books and op-eds about the world traveler’s legacy have attempted to account for this darker side of him, whether by providing firsthand insights into his behind-the-scenes personality (Vitale’s In the Weeds) or by interviewing the people in his life in order to draw some narrative throughline from dishwasher to beloved television star to agoraphobic celebrity (Charles Leerhsen’s Down and Out in Paradise: The Life of Anthony Bourdain). The 2021 documentary Roadrunner was a sincere attempt to do both. Using interviews with family, close friends, and crew members, along with plenty of footage from the television shows, Morgan Neville (director) did his best to piece together a mosaic of impressions related to Bourdain’s life and work, with the overall aim of contextualizing the suicide. There was a mission of public catharsis in the project as if it were a vehicle for processing the loss of a beloved television icon that many felt incredibly close to, or seen by, despite the distance between the man in reality and the man on screen. Along those lines, I think the film was a success. I watched it in a dark theater with other Bourdain enthusiasts. We laughed at his delectable soundbites while shedding plenty of tears in turn, and it was a special way of mourning such a great loss—a loss most fans likely found out about in isolation, whether via text, push notification, or cable news report. Still, in the past year, I’ve been yearning for another way of processing Bourdain’s absence: an account of what made his work so meaningful to so many people who did not know him in the way those in the documentaries, memoirs, and biographies did.

For me, the ultimate gift of Parts Unknown was Bourdain’s ability to show that there are—and continue to be—fascinating, underrepresented corners of the world that we ought to seek out and support as locals and travelers alike. As Bourdain said:

“If I am an advocate for anything, it’s to move. As far as you can, as much as you can. Across the ocean, or simply across the river. Walk in someone else’s shoes or at least eat their food.”

Back when I was feeling lost in Los Angeles with Bourdain as my guide, that’s exactly what I did. I moved. I explored my new city with an open mind and an appetite. I familiarized myself with its limited and underutilized public transit system, traveling every direction off the metro line that city bus routes would allow. As I trekked farther and farther away from home, each stop introduced me to a new corner of the city, from the untamed stretches of the Los Angeles river to the thriving ramen shops off Sawtelle Boulevard.

Other weekends, I stuck around Studio City and spent hours walking my way up and down Ventura Boulevard—from Universal City all the way to the 405—which I found rewarding precisely because these areas are largely ignored by mainstream media and so I had not consumed any preconceived cultural consensus that might intrude on or direct my Valley adventures. No one talked about The Valley, let alone recommended exploring it. Yet, familiarizing myself with all those stucco apartment complexes, two-story strip malls, sushi lunch specials, and kitschy car washes was in many ways more interesting than bouncing around more obvious places such as the notorious hipster neighborhoods of Echo Park or Silverlake. I learned from those walks that there was pleasure to be had in drawing distinctions between places, in knowing street names, coffee shops, tree canopies, baristas, bartenders, and happy hour deals, not to mention the fantastic Cuban spot lying just beyond the next traffic light (Here’s looking at you, Versailles). Thus, via the basic premise of Bourdain’s show—implied in the title Parts Unknown—I got a grip on what made Los Angeles a worthwhile place to explore. And the more I listened to his voice, the more he became a filter through which I reflected upon that experience.

On A Cook’s Tour, when he observes that palm trees have never looked more menacing than they do in Southern California, I recalled my own first impression of the city on my bus ride from LAX to Studio City—the towering trunks and fronds leaning over the highway like sentinels surveilling traffic—and how I would later learn that palm trees are non-native, an “exotic” ecological lie I would come to associate with every other ersatz feature of the city.

But the real highlight of that episode is a running bit in which Bourdain, beginning to understand the allure of Los Angeles, ponders the sorts of demoralizing things he would do to afford the Hollywood lifestyle. While enjoying a ride down Sunset in his rented convertible, he says: “God I love this car. I’m already thinking what outrage would I not perform, or commit, to hang onto this fine piece of material? Pauly Shore in Hamlet? Sure! I can write that.” It’s a sentiment all too familiar to us “Hollywoo” folks. But it isn’t until No Reservations and Parts Unknown that Bourdain truly begins to see Los Angeles through its distinct neighborhoods and immigrant cultures: Koreatown, Little Ethiopia, Filipinotown, Boyle Heights, Tehrangeles, and even Santa Monica (aka Little Britain). In his final Los Angeles episode, Bourdain’s voice-over begins, accompanied by images of a nurse, line cook, housekeeper, car washer, and produce workers:

“Los Angeles. Maybe the most filmed, most televised, most looked at place on Earth. It’s the landscape of our collective dreams. But what if we look at L.A. from the point of view of the largely unphotographed, the 47 percent of Angelenos who don’t show up so much on idiot sitcoms and superhero films, the people doing much, if not most, of the hard work of getting things done in this town?”

If I’ve learned anything from Bourdain’s work, this is the quote that embodies it: that we often can’t help but imagine places through the common images we’ve consumed of them. These dominant images shape our expectations, redouble our prejudices, and limit our notions of a place. Yet, when we are challenged by exciting, unsettling, or less familiar images of said places—from strip mall dim sum restaurants and Ethiopian coffee shops to vandalized “walk of fame” stars and charred Malibu mountainsides—we are forced to reckon with them and possibly even change ourselves in response. In the best episodes of Parts Unknown, that is what Anthony Bourdain and his crew accomplished. They reconceptualized the viewer’s notion of the world through Bourdain’s own reconceptualization of it.

Today, the majority of our collective media diet seems to encourage the exact opposite behavior. To photograph a particular place for social media—say, the Venice canals (L.A.) or the Walt Disney Concert Hall—is to verify that one is in the know about it as it continues to exist: undisputed in the cultural imagination. These popular photos are therefore a redundant, thoughtless act of consumption—a box to check, an unveiling of more of the same. Like the tourists at the “most photographed barn in America” from Don DeLillo’s White Noise (the only significance of which is that it is frequently photographed), they amplify a tendency that has less to do with experiencing a place than with extracting its beauty. At its worst, this behavior can destroy a place (see the Antelope Valley poppy fields trampled to death by L.A. influencers) or displace the people who live there (see the other Venice canals, where tourists outnumber locals). At best, it offers no more than the lukewarm affirmation of “likes” and “follows.”

When I traveled through Morocco, I never felt as if I were that unwelcome or disruptive presence that seems foundational to influencer culture, but I know that, if I ever go back, there are other things I would do to more deeply engage with the people I meet. At the very least, I would be less concerned with developing my own narrative and more concerned with understanding the narratives of those around me, and that’s largely thanks to the way Bourdain reoriented my attitude to the city I live in today.

After his suicide, I knew I would miss having his voice around. But I was also grateful for the work he left behind. As I continue to study Los Angeles, I do so with that Bourdainian drive to more fully engage with the Angelenos around me: the adventurous neighbors I mentioned earlier, the retired teacher in our building who regularly enlists me to move heavy objects about her apartment, a local bookstore owner fighting rent hikes in Santa Monica, the Italian restaurant owner who—for better or worse—can’t resist a controversial political conversation, the American Cinematheque members who take film preservation, presentation, and enrichment more seriously than the big studios, and all the friends and coworkers who have showed me around their respective neighborhoods.

In Los Angeles, like many of the places Bourdain has visited, this is a never-ending task. It is a city full of contradictions that manifest in experiential extremes. One day the concentration of multi-million dollar homes and luxury cars is enough to make you cynical about the possibility of equality in a hyper–capitalist landscape; the next day the announcement of a wildlife crossing has you optimistic about environmental progress in a landscape defined by infinite sprawls of concrete and asphalt roadway. Another day “La Sombrita,” an expensive and ineffective system of ridiculously small shade- and light-providing constructs at bus stops (supposedly addressing gender equity issues in the transit system, as women experience violence and harassment there), has you wondering if Los Angeles will ever reach its utopian public transportation goals. The next day you’re riding the Expo Line to the Festival of Books and attending talks with panelists who pose progressive solutions to the same problems while locating them in a richer historical understanding of the city’s many commuter communities. Another day the city radiates the carefree energy of La La Land (2016) or the leisurely pace of a Curb Your Enthusiasm episode; the next day it feels like the police state in Straight Outta Compton (2015). Perhaps these extremes of experience are the reason why Bourdain continued visiting the city over and over again across his shows and, eventually, in his web series Little Los Angeles. The place is as enigmatic as Bourdain himself.

I’m not sure what conclusions one can draw from the pain he endured while striving to make episodes reflective of the “real things” he absorbed or by doing the hard work of opening himself up to the lived experiences and histories of the people who hosted him. But I do know that what he gave through his work was enough to make me feel better about my immediate circumstances in Los Angeles. If Neville’s documentary did anything to help me process those feelings, it was because of one particularly moving sequence: the one where Brian Eno’s “The Big Ship” plays while Tom Vitale reflects on a comment Bourdain made. “[Tony] often talked about how, in an ideal world, he wouldn’t be in the show. It would be his point of view, like a camera moving through space.” As Vitale speaks, Neville hits us with point-of-view footage from Bourdain’s Instagram account along with clips from Parts Unknown sans Bourdain. As the footage jumps from West Virginia to India, Korea to Kenya, Marseilles to Myanmar, and so on, Bourdain’s voiceover comes in: “Travel isn’t always pretty. You go away, you learn, you get scarred, marked, changed in the process. It even breaks your heart.”

Without explicitly saying so, Neville conveys what it feels like to exist in a world without Bourdain. We can no longer watch him on TV, but as we travel we now have the gift of occupying his point of view and recalling his methods for engaging with the world: being a good guest, asking simple questions, pushing beyond mediocrity, and doing our best to empathize with the plights of people who, like the rest of us, are doing their best in the specific circumstances they find themselves in. Now on my walks across Los Angeles, I can picture him floating beside me like some ethereal projection, forever reminding me to stay curious and keep up an appetite for the strip mall around the corner.

While showing a nonna-run pasta joint in his Emmy-winning Rome episode, Bourdain’s voiceover relays: “Rome is a city where you find the most extraordinary of pleasures in the most ordinary things, like this place, which I am not ever going to tell you the name of.” ↩